Abstract

The purpose of the present investigation is to analyze the relation of frustration tolerance and delay of gratification with PhD-intention and expectations. We conducted one correlational and two experimental studies. In Study 1 (N1 = 171 undergraduates), we found the hypothesized positive association between delay of gratification and frustration tolerance and the intention to obtain a PhD. In Studies 2 and 3, we used experimental vignette designs. In Study 2, doctoral students and postdocs (N2 = 180) evaluated a fictitious student regarding PhD-intention and a successful PhD-process. As expected, students with high gratification delay and frustration tolerance were judged as more likely to start and complete a PhD than students described low in these volitional traits. In Study 3, we contrasted Study 2’s findings by asking employees of the private sector (N3 = 150) to rate the same students’ intention to join a company instead. None of the factors influenced participants’ judgments when it comes to a non-academic career track.

Résumé

Combien de temps puis-je attendre et combien de frustration puis-je supporter? Traits volitionnels et intention et recherche de doctorat des étudiants Le but de la présente enquête est d'analyser la relation entre la tolérance à la frustration et le retard de gratification avec l'intention et les attentes de doctorat. Nous avons mené deux études expérimentales. Dans l'étude 1 (N1 = 171 étudiants de premier cycle), nous avons trouvé l'hypothèse d'association positive entre le retard de gratification et la tolérance à la frustration et l'intention d'obtenir un doctorat. Dans les études 2 et 3, nous avons utilisé des modèles de vignettes expérimentaux. Dans l'étude 2, les doctorants et les postdoctorants (N2 = 180) ont évalué un étudiant fictif concernant l'intention de doctorat et un processus de doctorat réussi. Comme prévu, les étudiants ayant un retard de gratification élevé et une tolérance à la frustration ont été jugés plus susceptibles de commencer et de terminer un doctorat que les étudiants décrits comme faibles dans ces traits volitionnels. Dans l'étude 3, nous avons contrasté les résultats de l'étude 2 en demandant aux employés du secteur privé (N3 = 150) d'évaluer l'intention du même étudiant de rejoindre une entreprise à la place. Aucun des facteurs n'a influencé le jugement des participants lorsqu'il s'agit d'une carrière non universitaire.

Zusammenfassung

Wie lange kann ich warten und wie viel Frust kann ich ertragen? Volitionale Strategien und Promotionsabsicht und -verfolgung Ziel der vorliegenden Untersuchung ist es, den Zusammenhang von Frustrationstoleranz und Belohnungsaufschub mit Promotionsabsicht und Erwartungen zu analysieren. Wir haben eine korrelative und zwei experimentelle Studien durchgeführt. In Studie 1 (N1 = 171 Studierende) fanden wir den erwarteten positiven Zusammenhang zwischen Belohnungsaufschub und Frustrationstoleranz und der Promotionsabsicht. In den Studien 2 und 3 haben wir experimentelle Vignettendesigns verwendet. In Studie 2 evaluierten Promovierende und Postdocs (N2 = 180) eine fiktive Studentin hinsichtlich der Promotionsabsicht und einem erfolgreichen Promotionsprozess. Wie erwartet wurden Studierende mit hoher Fähigkeit zum Belohnungsaufschub und Frustrationstoleranz als wahrscheinlicher beurteilt, eine Promotion beginnen zu wollen und erfolgreich abzuschließen als Studierende mit geringer Ausprägung dieser volitionalen Eigenschaften. In Studie 3 kontrastierten wir die Ergebnisse von Studie 2, indem wir Beschäftigte des Privatsektors (N3 = 150) baten, auf Grundlage derselben Personenbeschreibungen die Absicht, einen Direkteinstieg ins Unternehmen zu wählen, einzuschätzen. Keiner der Faktoren beeinflusste die Einschätzung der Teilnehmenden in Bezug auf eine nicht-akademische Laufbahn.

Resumen

¿Cuánto tiempo puedo esperar y cuánta frustración puedo soportar? Rasgos volitivos e intención y búsqueda de doctorado de los estudiantes El propósito de la presente investigación es analizar la relación de la tolerancia a la frustración y el retraso de la gratificación con la intención y expectativas del doctorado. Realizamos dos estudios experimentales. En el Estudio 1 (N1 = 171 estudiantes universitarios), encontramos la asociación positiva hipotética entre el retraso de la gratificación y la tolerancia a la frustración y la intención de obtener un doctorado. En los Estudios 2 y 3, utilizamos diseños de viñetas experimentales. En el Estudio 2, estudiantes de doctorado y posdoctorados (N2 = 180) evaluaron a un estudiante ficticio con respecto a la intención de doctorado y un proceso de doctorado exitoso. Como era de esperar, se consideró que los estudiantes con un alto retraso en la gratificación y tolerancia a la frustración tenían más probabilidades de comenzar y completar un doctorado que los estudiantes descritos con bajos en estos rasgos volitivos. En el Estudio 3, contrastamos los hallazgos del Estudio 2 al pedirles a los empleados del sector privado (N3 = 150) que calificaran la intención del mismo estudiante de unirse a una empresa. Ninguno de los factores influyó en los juicios de los participantes cuando se trata de una carrera profesional no académica.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transition into a PhD-program is a valuable career goal for graduate students. It is the first step toward an academic career, and it may well lead to optimized career options outside of academia (Nerad, 2004). Concerning the recruitment of the most talented students, academic institutions compete with private companies (e.g., Bercovitz & Feldman, 2008). In fact, many students decide against a PhD, although they would have the intellectual ability to successfully complete it and to pursue an academic career (e.g., Mueller et al., 2015). But to date, there is still little knowledge about what fuels students’ intentions for pursuing a PhD or what keeps them from entering a PhD-program. Previous studies (e.g., Brailsford, 2010; Mueller et al., 2015) considered aspects of motivation, academic achievement, and contextual factors. However, so far, dispositional characteristics critical for (academic) goal pursuit and achievement, such as individual differences in self-control capabilities, have been widely neglected. Clearly, entering a PhD-program is only a first step. Students already enrolled in a PhD-program often encounter difficulties during their studies (Goller & Harteis, 2014; Owens et al., 2020). This may lead to dissatisfaction with the PhD-process (Van Rooij et al., 2021), delayed completion, and even attrition (e.g., Lovitts, 2008). In fact, international studies report dropout rates of 50% on average (e.g., BMBF, 2017; Council of Graduate Schools, 2008). Given the lack of research on PhD-intention and the relevance of this topic, our aim was to investigate whether specific volitional traits are related to the intention to obtain a PhD. As outlined below, past research has shown that individual factors are considered important for a successful PhD-process. There is also first evidence that self-regulatory beliefs and capabilities are among those individual factors (e.g., Castro et al., 2011). Instead of focusing on a rather broad array of personality traits associated with goal-related action regulation, we decided to concentrate on two specific volitional traits that we will argue to be particularly important in successful PhD-processes, namely frustration tolerance and delay of gratification. Whereas delay of gratification is defined as the ability to forego immediate rewards for the sake of those that are more valuable long term (Mischel, 1996), frustration tolerance is the level of a person’s ability to persist in goal pursuit despite experiencing frustration (Meindl et al., 2019; Wilde, 2012). Of course, as previous studies have shown, many different factors including institutional characteristics, the quality and quantity of supervision, the student–advisor relationship, and financial considerations contribute to PhD-completion and satisfaction as well (e.g., Van Rooij et al., 2021). It is not our goal to maximize the number of considered predictors but to conduct research that focuses on a specific set of factors of interest building on frameworks of action and self-regulation. In fact, many past studies did not adopt a guiding theoretical framework as a rational for variable choice (Van Rooij et al., 2021). In this study, we use the model of action phases (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2018; Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987) and the social-cognitive theory of self-regulation (Bandura, 1991) to investigate PhD-intention and PhD-success from a goal-oriented perspective that clearly emphasizes the role of the individual as an active agent. We define PhD-intention as a deliberate goal to pursue a PhD, and we define PhD-success as both experiencing (work) satisfaction during the PhD as well as completing it successfully. Please note that in this paper we use the terms goal and intention interchangeably.

Theoretical framework

Volition is characterized as a part of the self-regulatory system (e.g., Snow, 1989) that comprises “psychological control processes that protect concentration and directed effort in the face of personal and/or environmental distractions” (Corno, 1993, p. 16).

Based on a separation of motivation and volition, the model of action phases (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2018; Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987) divides the course of action into four phases with different functions: The first phase (predecisional phase) is characterized by forming the goal intention. An individual has to decide which goals to pursue. Having formed the goal intention, the second task (preactional phase) is to consider the best strategies and formulate plans to attain the chosen goal. In the third phase (actional phase), the individual tries to successfully reach the goal by implementing the plans made in the preactional phase. In this phase, the individual has to deal with setbacks and has to increase effort in case of difficulties. Finally, in the fourth phase (postactional phase), the individual evaluates the action outcome achieved. The model of action phases addresses the formation of a goal intention and the initiation of goal pursuit actions as two major aspects within the goal striving process. The process of choosing a goal is determined by that goal’s value as well as the expectancy that it can be achieved (Brandstätter et al., 2003). A type of expectancy beliefs is (academic) self-efficacy, which is grounded in Bandura’s social-cognitive theory and defined as the belief in one’s own capabilities to achieve goals (Bandura, 1991; Bergey et al., 2018). We argue that forming the intention to obtain a PhD as well as its successful pursuit demands frustration tolerance and the ability to delay gratification as two specific volitional components. How so? According to Bandura (1991, 1997) the most important way in building academic self-efficacy is through mastery experiences. As we will present below, students with high frustration tolerance and delay of gratification are more likely to succeed in school and university. Over time, they may become convinced that hard work and own efforts will pay off in the long run and, as a consequence, tend to choose more intellectually challenging goals and persist longer when confronted with failure and setbacks while pursuing them. Indeed, studies have shown frustration tolerance and delay of gratification to be positively correlated with (academic) self-efficacy (e.g., Hoerger et al., 2011; Meindl et al., 2019). Clearly, this line of argumentation puts an emphasis on expectancy characteristics as predictors for goal setting and pursuit. We suggest that given equal interest in scientific contents and given equal cognitive prerequisites (e.g., general mental ability, specific prior knowledge acquired during undergraduate studies), seeing oneself able to deal with the self-regulatory demands inherent in the PhD-process fosters the intention to enter a PhD-program and helps to succeed. As it might be suggested, however, that it is a challenge to experience frustration or little immediate reward even for those who know that they are very well able to deal with it, one might put it also the other way round: Knowing that one has difficulties in dealing with frustration and gratification delays might keep one from starting a PhD.

Individual factors related to PhD-success: A review of the literature

So far, psychological research on individual factors influencing students’ PhD-intention is scarce. Individual factors have mainly been considered in studies focusing on students’ attrition and persistence. According to Bair and Haworth (2004), personal and psychological variables represent a relatively new and worthwhile research route in the study of doctoral students’ success. Lovitts (2008) analyzed the difficulties doctoral students face during their transition from ‘course-takers’ to independent researchers. She interviewed focus groups consisting of two to five faculty members (mainly professors supervising doctoral students). Participants described students who made the transition with relative ease and those who had difficulties or even failed. PhD-supervisors mentioned patience, willingness to work hard, initiative, persistence, and intellectual curiosity to be related to a successful PhD-transition. Some students having difficulty making the transition were described as displaying an inability to deal with frustration, fear of failure, intolerance of ambiguity, inability to delay gratification, and lacking self-confidence.

To better understand questions concerning the academic success of PhD-students, Goller and Harteis (2014) conducted a qualitative interview study with ten German faculty members. Interviewees named ambition and a tolerance for frustration and failure as well as agentic activities such as proactive networking and feedback-seeking as key personality-related factors influencing academic success. However, these studies focused on the perceptions of faculty advisors. Yet, it is important to consider what personal attributes students themselves identify as contributing to their success.

Results from Wao and Onwuegbuzie’s (2011) quantitative–qualitative mixed research study with graduate students and faculty members showed that students and faculty agree in that the motivation to attain set goals despite experiencing obstacles is the most important predictor for the time taken to the doctorate (TTD), albeit different personal and institutional factors, as well as their interplay, are also relevant. Accordingly, in a questionnaire study with doctoral students of industrial engineering and management Martinsuo and Turkulainen (2011) showed that beyond peer and supervisor support, students’ plan and goal commitment were positively related to study progress. In a qualitative study with 76 PhD-completers, Spaulding and Rockinson-Szapkiw (2012) identified the preparedness to make personal sacrifice (i.e., time with family and friends, leisure activities, and sleep), handling intervening life events (e.g., birth of a child, death, illness, or personal limitations), and overcoming dissertation challenges (e.g., conducting statistics, learning new technologies, balancing family, and work-related responsibilities) as being essential for the successful pursuit of a doctoral degree. Further qualitative studies reported that successful PhD-students, as compared to unsuccessful ones, are characterized by higher self-efficacy beliefs (e.g., Castro et al., 2011), as well as the feeling of making progress on a meaningful research project and the ability to self-regulate one’s learning (Devos et al., 2017).

Delayed gratification and tolerance for frustration

Delay of gratification is seen as a key factor in predicting academic achievement. Mischel et al. (1988) implemented a series of experiments to understand the behavioral decision-making process in children. Preschoolers were asked to choose between obtaining one marshmallow immediately or two marshmallows after a waiting period (Mischel, 1996). Ten years after their initial experiments, Mischel et al. (1988) contacted the families of these children once again. Parents of those children who had waited longer in the initial experiment described their teenagers as more academically and socially competent, as better at coping with frustration and stress, and as more mature. Beyond parental ratings, Shoda et al. (1990) discovered that the time delay in the experiment correlated significantly with the SAT scores: children who could delay longer had better results on the college entrance examination.

The importance of delayed gratification in research and in writing a dissertation is evident, as research is a long-term process and dissertations take years to be completed (Lovitts, 2008). When seeking publication in peer-reviewed journals, there is a high probability of several rounds of rejection. Spending time on the dissertation requires personal sacrifices to be made, such as devoting less time to family, friends, and even sleep (Spaulding & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2012). Additionally, forms of positive reinforcement, like acknowledgement or appreciation, are often scarce (Lovitts, 2008). Another aspect concerns the financial situation during the PhD. Please note that in the country in which our participants reside (i.e., Germany), doctoral students typically have an employment contract with full social security. But even if doctoral students work as paid research associates, wages are generally low compared to other positions in academia or industry, which is partly due to only part-time employment offered to PhD-candidates and low-income development during the PhD-phase (Mueller et al., 2015; Roach & Sauermann, 2010). However, a PhD may contribute to a person’s future financial gains (Ehrenberg, 2005). Beyond individual goals, delay of gratification is also important for cooperative goals (Koomen et al., 2020). In a recent study, Koomen et al. (2020) used a modification of the marshmallow test, in which the children were only rewarded if both partners of the dyad resisted temptation. Compared to a standard version of the test (solo condition), children were more likely to delay gratification in the dependent condition. The results suggest that cooperation elicits motivation to delay gratification. Applied to doctoral success, delaying gratification can be meaningful for cooperations to succeed, such as working on joint publications with other doctoral students or maintaining a collaborative relationship with the advisor. Finally, candidates who plan to stay in the academic system after completing their degrees need a lot of patience, because it is a long and hard quest to become a full professor, and only a small number of those early career scientists aiming for professorship will finally succeed. Only 15–20% of the US PhD-holders (and even fewer in European countries) who continue into a postdoc will ultimately achieve permanent academic positions (Powell, 2015).

Just as delay of gratification, frustration tolerance is likely to play a role in predicting academic success. A lack of frustration tolerance can negatively influence academic achievement in several ways: students who have difficulties in dealing with frustration or failure are known to procrastinate. Studying can become a frustrating task and at worst lead to lower grades or even drop out (Wilde, 2012). The challenge is to stay motivated and to persist in goal pursuit in spite of setbacks. Meindl et al. (2019) showed that students with higher frustration tolerance earned higher grade-point averages and standardized test scores in math, reading, and science and persevered longer toward a university degree.

We apply frustration tolerance to the PhD-process, because, even in students who rarely experienced frustration during their undergraduate coursework, the transition to a doctoral program may provoke unknown situations (Lovitts, 2005). These situations, in turn, may lead to worries and doubts. During the research process, failure is unavoidable and essential for improving one’s work (Lovitts, 2005). Researchers have to repeat experiments, revise research questions and methodology, or take essays through numerous drafts (Lovitts, 2008). All in all, doctoral students are required to handle the frustration of realizing (or being told) that work needs to be redesigned and revised. It is crucial to be able to learn through critique and to respond well to feedback provided by the supervisor or peer reviews without perceiving it as ego-threatening (Owens et al., 2020). Often these are experiences graduate students are not used to (Lovitts, 2005). Furthermore, such unexpected research challenges easily lead to uncertainty about the dissertation’s progress, which can be a reason for frustration and stress (Cornwall et al., 2019; Goller & Harteis, 2014). Other sources of distress doctoral candidates face are as follows: being behind one’s initial time plan, time pressure, motivation problems, negative emotions associated with one’s work, doubts regarding abilities or strengths, student–advisor conflicts, or work-life balance problems (Cornwall et al., 2019; Devos et al., 2017; Goller & Harteis, 2014). Therefore, it is important that PhD-students learn to overcome these kinds of frustration by developing a “never-give-up attitude” (Bair & Haworth, 2004). As two self-regulatory strategies, frustration tolerance and delay of gratification may be helpful for coping with doctoral stress. Recent studies have emphasized that the stress PhD-students experience may result in serious consequences, such as impaired mental health and turnover intentions (Levecque et al., 2017). According to Mackey and Perrewé (2014), self-regulation plays a critical role in the stress process, potentially explaining “why some individuals are able to learn and adapt to stressors effectively, and others are unable to do so” (Mackey & Perrewé, 2014, pp. 260–261). By exerting behavioral control, individuals can refrain from inappropriate responses when experiencing negative emotions (e.g., not withdrawing from a manuscript when feeling anger after receiving a rejection) and engage in constructive coping behaviors instead (e.g., increase effort). Moreover, research indicates that individuals with high self-control develop beneficial habits and routines to avoid temptations and stress (Galla & Duckworth, 2015). Indeed, the establishment of regular writing routines (e.g., writing during scheduled hours) is strongly recommended for graduate students to succeed (e.g., Silvia, 2019).

The present research

The three studies build upon each other in a sequential manner. Study 1 was designed to initially test the correlational association between frustration tolerance and delay of gratification with the intention to obtain a PhD. In Study 2, we replicated and extended the results of Study 1 using an experimental scenario (vignettes), which allowed testing as to whether personality descriptions of a fictitious university student had an effect on participants’ judgment of the probability that the student proceeds into a PhD-program, experiences work satisfaction, and successfully completes the PhD. Hence, here not only the intention to start a PhD is investigated, but also expectations concerning enjoyment and completion, i.e., experiences and outcomes of later action phases. In Study 3, we used a similar experimental scenario as in Study 2 to test whether the same personality descriptions of a fictitious student had an effect on judgment of the probability that the student would join a private company rather than obtaining a PhD. This third step was important to establish specificity, i.e., to support the assumption that the two volitional traits are particularly relevant for the (early) academic track.

Study 1

In our first study, we investigated the correlational relationship between frustration tolerance and delay of gratification with PhD-intention. We tested the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive correlation between the capability to tolerate frustration and the intention to obtain a PhD.

Hypothesis 2

There is a positive correlation between the ability to delay gratification and the intention to obtain a PhD.

Please note that one could have formulated the hypotheses in terms of lack of volitional capabilities such that, for instance, low tolerance of frustration is negatively related to the intention to start a PhD. For the actual test of the hypotheses, this makes no difference, although.

Study 1: Method

Procedure and participants

The data were collected in 2016–2017 using an internet-based survey. Participants were recruited via internet platforms and mailing lists from universities in Germany. A total of 171 Bachelor’s (13.5%) and Master’s students from a variety of fields of study (psychology [34.9%], STEM-fields [28.3%], language and cultural studies [15.1%], economics and law [13.2%], teaching [7.2%], other/not specified [1.3%]) participated. Of these, 62.6% were women. Their ages ranged from 18 to 53 years (M = 25.90, SD = 5.20).

Measures

All instruments were self-assessment scales. The questionnaire items were originally composed in English and translated into German by a bilingual research assistant. The German items were then translated back into English by a native English speaker to verify semantic equivalence (Brislin et al., 1973). The items translated back were found to be highly comparable in content to the original version. Frustration tolerance was measured using six items of the Frustration Tolerance Scale (Ruiz et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .88, which was comparable to the study of Ruiz et al., 2016. An example is “I try to solve a problem even though I may not be successful” (6-point Likert scale, 1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree; M = 4.69, SD = .80). Delay of gratification was measured with five items of the Delaying Gratification Inventory (subscale “achievement”; Hoerger et al., 2011). Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .72, which was slightly lower than in the study of Hoerger et al., 2011. A sample item is “I am capable of working hard to get ahead in life” (6-point Likert scale, 1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree; M = 4.18, SD = .85). The scale showed positive correlations with, for instance, GPA score, diligence, and self-efficacy (Hoerger et al., 2011). In the present study, the bivariate correlation of frustration tolerance and delay of gratification scales was r = .23 (p < .01). To test the distinction between the two measures, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) using maximum likelihood estimation with Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). The model fit is assessed by evaluating the model’s RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation), SRMR (standardized root mean square residual), and CFI (comparative fit index). RMSEA and SRMR should be < .08 and CFI should be > .90 to imply a good fit (Kline, 2005). The two-factor model with frustration tolerance items loading onto the first factor and delay of gratification items loading onto the second factor yielded a better fit to the data than the single factor model: χ2 (43) = 98.18, p < .001; CFI = .92, RMSEA = .09, SRMR = .09 versus χ2 (44) = 226.18, p < .001; CFI = .75, RMSEA = .16, SRMR = .12, (N = 171). A Chi-Square difference test for the model comparison was significant: Model 2 fits significantly better than Model 1 (Δχ2 = 128.01, Δdf = 1, p < .001). This factor structure supported the distinctiveness of both constructs. Item loadings are shown in Table 1.

PhD-intention

We measured the intention to obtain a PhD with three self-generated items (5-point Likert scale, 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; M = 2.94, SD = 1.44; α = .94). We firstly defined PhD-intention as the deliberate goal to pursue a PhD and then generated three items upon this definition. The items were as follows: (1) “I would like to earn a PhD,” (2) “I am determined to write a dissertation,” and (3) “Pursuing a PhD is none of my intended goals” (reversely coded). A maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation displayed a one-factor structure (all item loading > .85). The eigenvalue for this factor was 2.67, accounting for 89.12% of the total variance.

Study 1: Results

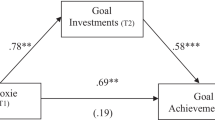

Consistent with our hypotheses, PhD-intention was significantly correlated with frustration tolerance (r = .34, p < .001) and delay of gratification (r = .23, p < .01). To further analyze their predictive power, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed. As previous studies revealed age to be negatively related to PhD-completion and women to have a higher dropout rate from the PhD-program (e.g., Groenvynck et al., 2013), we added age and gender as control variables. After controlling for these sociodemographic factors, frustration tolerance and delay of gratification were still significantly related to PhD-intention (ß = .31, p < .001 and ß = .18, p < .05; R2 = .17, p < 001). To test for multicollinearity among the two independent variables we used the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF values for frustration tolerance and delay of gratification (1.07 and 1.06) did not exceed the standardized VIF level (< 10.0), indicating the absence of multicollinearity among them. The results are summarized in Table 2. They are consistent with our hypotheses that frustration tolerance and delay of gratification are significant predictors of PhD-intention. These findings served as an initial correlational demonstration of the positive relationship between both constructs and the intention to obtain a PhD. Please note that it was not our goal to conduct a study that comprised all kinds of psychological constructs that might be relevant in forming PhD-intentions (content-related interests, aspiration for social prestige, etc.) but to demonstrate that specific volitional traits should be taken into account. However, as we asked undergraduates about their PhD-intention, we could not consider how volitional traits affect the subsequent PhD-process (e.g., enjoyment of academic work, progress in one’s PhD-studies; e.g., Goller & Harteis, 2014).

Study 2

In Study 2, we investigated not only how volitional traits are related to starting a PhD but also to work satisfaction and the likelihood of PhD-completion. We did so using an online vignette experiment with a between-subject design. Participants (doctoral students and postdocs) were experts for the academic work environment and the PhD-process. In this vignette study, person perception ratings allowed us to examine the judgment of a described doctoral student’s PhD-completion and work satisfaction beyond initial PhD-intention.

Vignette experiments have several advantages compared to traditional survey questions (Steiner et al., 2016). Most importantly, when designed properly, they combine the advantages of a classical experiment’s internal validity and a survey’s external validity by compensating for each approach’s weakness (Steiner et al., 2016). In terms of internal validity, the vignette approach offered us the opportunity to hold the person descriptions constant with respect to, for instance, the intellectual capabilities (as reflected in students’ good grades) and intrinsic motivation during undergraduate studies (as reflected in the pleasure they had in spending time on their studies; see Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). We tested the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

A student with a high ability of delay of gratification is judged as being more likely (a) to start working on a PhD, (b) to enjoy PhD-work, and (c) to successfully complete it than a student with a low ability of delay of gratification.

Hypothesis 2

A student with high frustration tolerance is judged as being more likely (a) to start working on a PhD, (b) to enjoy PhD-work, and (c) to successfully complete it than a student with low frustration tolerance.

Additionally, we explored if there were any differences between (the degree of) frustration tolerance and delay of gratification with respect to the judgment of the vignette students regarding their PhD-intention, PhD-completion, and work satisfaction during PhD.

According to the model of action phases (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987), volitional strategies are particularly important at an advanced stage in the course of action (preactional and actional phases) when the goal intention is finally articulated and goal pursuit has actually started. The inclusion of ratings on work satisfaction and PhD-success provided the opportunity to analyze whether there were different effects of frustration tolerance and delay of gratification at different PhD-stages.

Study 2: Method

Participants

A total of 180 persons (53.3% female; M = 33.33 years, SD = 8.34) from a variety of disciplines (humanities and cultural studies [43.0%], economics and law [23.3%], STEM-fields [16.9%], psychology and social sciences [16.3%], other/not specified [.5%]) participated. We recruited doctoral students (n = 126) as well as postdocs (n = 54) via internet platforms and mailing lists from German universities to analyze possible differences due to shorter or longer working experiences in the academic field.

Materials and procedure

The study was conducted online. Participants were randomly assigned to one of six vignettes. All vignettes were developed by the authors and pretested in a pilot study.Footnote 1 They were developed and presented to the participants in German. Each vignette described a prospective PhD-student’s past academic achievements, attitudes, and behavior. Vignettes were identical except for the description of a person’s volitional personality characteristics. These characteristics were the central manipulation of frustration tolerance (high vs. low) or delay of gratification (high vs. low) with six conditions: (1) frustration tolerance_high, (2) frustration tolerance_low, (3) delay of gratification_high, (4) delay of gratification_low, (5) frustration tolerance and delay of gratification combined_high, and (6) frustration tolerance and delay of gratification combined_low. Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 show the first four vignettes. In the two combined conditions (5 and 6) the identical text of the matching single vignettes was merged (e.g., frustration tolerance_high and delay of gratification_high).

After reading the vignette, participants answered four questions serving as the dependent variables, whereby the first two questions concerned PhD-intention (r = .70): 1. Do you think Lisa R. will apply for this PhD-student position? 2. Do you think she will start the PhD-program in case of acceptance? 3. In case she starts the PhD-program, do you think she will enjoy working as a PhD-student? 4. In case she starts the PhD-program, do you think she will successfully complete it? Responses were rated on a six-point scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 6 (very likely). Please note that in the literature, behavior intentions were differentiated from behavioral expectations, with the latter referring to the “individual’s self-prediction of his or her future behavior” (Warshaw & Davis, 1985, p. 213). Concerning this definition and the typical use of likelihood estimations as response format in behavioral expectation research, at least the first two questions participants answered to estimate the student’s PhD-intention could be classified as behavioral expectations. However, as behavioral expectations typically refer to habitual everyday behavior we prefer to stick to the term intention.

Study 2: Results

Firstly, we checked for any effects of gender on PhD-status. In a 2 × 2 × 6 MANOVA of gender, PhD-status, and vignette on the dependent variables we found no main effects of participant’s gender or PhD-status nor interactions with gender or PhD-status.

The MANOVA revealed significant main effects of the factor vignette on the four dependent variables referring to PhD-intention, PhD-completion, and work satisfaction during PhD, Fs(5,153) = 11.68 (η2 = .276), 10.36 (η2 = .253), 33.10 (η2 = .520), and 36.30 (η2 = .543), respectively (all ps < .001). Bonferroni Post hoc tests showed that the differences between the conditions frustration tolerance_high vs. frustration tolerance_low (all ps < .05) as well as delay of gratification_high vs. delay of gratification_low (all ps < .05) were significant for all dependent variables (see Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8). These results were consistent with our hypotheses. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that there were no differences between the conditions frustration tolerance_high vs. delay of gratification_high (all ps > .10), as well as frustration tolerance_low vs. delay of gratification_low (all ps > .10).

Results confirmed our hypotheses: a graduate student with high frustration tolerance and high ability to delay gratification was judged as more likely to proceed into a PhD-program, complete the doctorate more successfully, and enjoy that type of work more than a student with low frustration tolerance and low ability to delay gratification. There was no difference between frustration tolerance and delay of gratification for participants’ judgements. Comparing the F and η2 coefficients indicates that the effects were slightly higher for the questions concerning work satisfaction and PhD-success than to applying/entering a PhD-position. In summary, this is first evidence of volitional strategies that are considered particularly important at a later stage of action process, as suggested by the model of action phases.Footnote 2

Study 3

Thus far, Study 1 and Study 2 have provided support for our hypotheses regarding the assumed importance of frustration tolerance and delay of gratification for PhD-intention, PhD-success, and work satisfaction. However, one could argue that these abilities represent some general skills that are important for starting a career and experiencing work enjoyment in other occupational fields as well. To additionally rule out this alternative explanation, we conducted a third study. In this study, we investigated how a graduate student with a high vs. low degree of frustration tolerance or gratification delay would be judged regarding the intention to enter a private company after university graduation (as compared to the intention to obtain a PhD) using an online vignette experiment with a between-subject design. To ensure that our participants had the expertise to judge a student’s intention to enter a private company, our sample consisted of raters that were employed in the private sector.

Study 3: Method

Participants

Data were collected from a sample of 150 employees (39.3% female) from the private sector. Participants were recruited via internet platforms, mailing lists, business-related social networking services, and newsgroups. They were also asked to share the invitation email with colleagues. All participants held university degrees, 18.0% of them were PhD-holders. They came from a variety of fields of study (STEM-fields [51.4%], psychology [23.3%], economics and law [18.5%], humanities [5.5%], other/not specified [1.4%]) and were employed in different working areas (research, development, and production [25.2%], human resources and health care [20.1%], executive board [11.5%], customer service [10.8%], consulting [8.6%], public relations [4.3%], IT management [4.3%], quality management [3.6%], purchasing [2.9%], sales and distribution [2.9%], controlling [1.4%], other/not specified and self-employed [4.4%]). Their ages ranged from 25 to 67 years (M = 42.48; SD = 11.23). Their working experience ranged from 1 to 45 years (M = 15.52; SD = 11.23). Participants were recruited via email to take part in the web-based vignette study at any time they wanted.

Materials and procedure

As in Study 2, participants were assigned to one of six vignettes. After reading the vignettes, participants answered three questions, which served as the dependent variables. The first two questions refer to the intention to start a job in a private company (r = .62): 1. Do you think Lisa R. will apply for this position? 2. Do you think she will accept employment in case of acceptance? The last question was used to assess work satisfaction: 3. In case of employment, do you think she will enjoy the work? Responses were given on a six-point scale ranging from 1 (very unlikely) to 6 (very likely).

Study 3: Results

As in Study 2, we first tested whether gender had any effects on the dependent variables intention to start a job in a private company and work satisfaction. Therefore, we conducted a 2X6 MANOVA of gender and vignette and found no main effects of gender or a significant interaction on any of our dependent variables.

The MANOVA did not reveal a significant main effect of the factor vignette on the dependent variables, Fs(5,138) = 1.60 (p = .16), 1.16 (p = .33), and 1.87 (p = .10). Hence, whereas in Study 2, a high degree of frustration tolerance and delay of gratification fostered perceptions of another person’s PhD-intention, completion, and work satisfaction, Study 3 showed that neither high frustration tolerance nor the ability to delay gratification was perceived as relevant for the intention to enter a private company and to enjoy working there. Combining our results from theses experimental studies, they support the assumption that high frustration tolerance and delay of gratification are perceived as being specifically important to the PhD-process but not for any kind of early career path that university graduates might take.

Discussion

Based on the model of action phases (Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987), social-cognitive theory of self-regulation (Bandura, 1991) and the specific demands of a successful PhD-process (e.g., Lovitts, 2008), we assumed frustration tolerance and delay of gratification to be associated with PhD-intention and progress. In Study 1, we showed that both constructs were positively related to PhD-intention. To further analyze this pattern of results, we conducted Study 2 using an experimental vignette design. We showed that participants (doctoral students or postdocs) judged a fictitious graduate student with high frustration tolerance or high delay of gratification as more likely to proceed into a PhD-program, to enjoy that type of work, and to complete the doctorate than a student with low frustration tolerance and delay of gratification. Both volitional abilities were equally relevant for these judgements. Furthermore, results suggest stronger effects for later PhD-stages. Therefore, findings are in line with the assumption of the model of action phases (Achtziger & Gollwitzer, 2018; Heckhausen & Gollwitzer, 1987). In Study 3, we additionally found that if participants (employees from the private sector) had to rate the decisions of the same fictitious student regarding the entry into a private company directly after graduation (instead of deciding to obtain a PhD), frustration tolerance and delay of gratification were unpredictive. This is important to note because it suggests these two volitional components to be perceived as relevant for academic career goals.

Our findings are in line with theory and qualitative evidence (Goller & Harteis, 2014; Lovitts, 2008) suggesting that unsuccessful PhD-students might have difficulties dealing with frustration and delayed gratification. The importance of both volitional constructs relates also to the finding of Devos et al. (2017), which stresses the feeling of making progress versus being “stuck” for doctoral success. We argue that delay of gratification and frustration tolerance are perceived as being relevant for the PhD-process because of their importance to overcome phases of low progress and stagnation, since such situations are a source of frustration in itself and demand to stay committed to one’s long-term goal (i.e., completing the dissertation successfully).

Clearly, there are other multiple factors that account for the remaining variance in PhD-progress, including characteristics of the PhD-project, quality of supervision, and critical life events (e.g., Van Rooij et al., 2021). Thus, having high frustration tolerance and delay of gratification is no guarantee for successful PhD-completion. But they represent an invaluable prerequisite for PhD-success. Also, they might be intertwined with other crucial factors that shape or hinder PhD-completion. Being components of trait self-control, for instance, both abilities may represent essential strategies for coping with stress, which often accompanies doctoral education (e.g., Cornwall et al., 2019).

Strengths, limitations, and implications for future research

We combined correlational and experimental methods to investigate the relationship of two volitional traits and students’ PhD-intention in more depth and to strengthen validity of the results (i.e., methodological cross-validation). Additionally, experimental vignette methodology allowed us to manipulate independent variables, thereby increasing internal validity while simultaneously enhancing external validity through realistic and credible person descriptions (e.g., Aguinis & Bradley, 2014). But, as mentioned above, the decision to obtain the PhD, as well as its successful completion, also depends on many other factors, which we did not consider (e.g., intrinsic academic motivation, quality of the student–advisor relationship; Litalien & Guay, 2015; Mueller et al., 2015). Further studies are required to complete the picture (e.g., by determining the incremental prognostic validity).

Our studies have some further limitations that need to be discussed. Due to the cross-sectional nature of Study 1, inferences about causality or directionality are precluded. Furthermore, we asked students about their intentions to obtain a PhD, which might not reflect the actual decision they are going to take. In other words, while the consideration of pursuing a PhD-degree is necessary, it is only the first step in the PhD-process. Further research, especially longitudinal studies, is needed to follow students from the start of a PhD-program to actual graduation (or dropout).

Additionally, Studies 2 and 3 used fictitious scenarios. Therefore, we cannot be sure if a student similar to the one that we described would indeed apply for the PhD-position (or a job in a private company). Moreover, we restricted the scenario to a university graduate from economics. It is known, however, that doctoral attrition rates are higher in humanities and social sciences compared to natural sciences (CGS, 2008). Therefore, future studies should consider possible differences between fields of study.

From a theoretical point of view, two additional aspects deserve closer elaboration. Firstly, another important factor to be taken into account is students’ trust in environmental reliability, or more precisely, in the academic system’s actual rewards. In a modification of the classic “delay of gratification” task (where children had to choose between one marshmallow directly or two after a waiting period), Kidd et al. (2013) demonstrated that giving children a hint that the experimenter was not reliable led to a reduction in children’s waiting times. Considering these results, one could argue that the variance in PhD-intention is also due to differences in student’s trust in actually getting rewards (e.g., a well-paid position after PhD-completion). This confidence may affect their actual willingness to tolerate frustration and to delay gratification. Second, while it appears straightforward to see volitional capability as being crucial for successful PhD-pursuit and completion, we still need to dive deeper into the mechanisms of the empirically identified positive correlations between delay of gratification and frustration on the one side and PhD-intention on the other side. Do those who are able to delay personal rewards and tolerate frustrating events would want to start a PhD more than others because past mastery experiences taught them that it makes them happy and proud to successfully deal with difficult tasks? Or are the strenuous challenges and setbacks to be expected during a PhD-phase just something these volitionally capable individuals do not worry about, whereas those who have difficulties in dealing with frustration and delay gratification might be kept from starting a PhD even if their content-related interest in a PhD-topic is high?

Practical implications

From a practical point of view, our research offers insights for career counseling on how to develop measures for the future PhD-student orientation process. Our results can guide educators in helping students to decide whether engaging in doctoral studies really fits their interest and skills. In Germany, for instance, many students who start a PhD are not interested in pursuing an academic career afterwards and see benefits in getting a PhD-degree for their non-academic career paths (e.g., earning higher salaries in non-academic jobs; Mueller et al., 2015). Some of those students, however, are not sufficiently aware of the requirements of earning a PhD and the challenges PhD-students typically face. Also, universities should offer doctoral students clear information on what is required to prevent frustration from the beginning.

We focused here on inter-individual differences in frustration tolerance and delay of gratification. Per definition, such person characteristics display a certain stability, although to a lesser degree than traditional personality traits (e.g., Big Five). But most importantly, frustration tolerance and delay of gratification can also be strengthened by training interventions and mastery experiences (e.g., Sung et al., 2013). Thus, with respect to institutional training programs, volitional strategies should be a topic. Those young people who want to start a PhD or who are already enrolled in a PhD-program might highly profit from trainings in self-management.

Moreover, counselors and supervisors should be aware of the volitional challenges PhD-students face. Our results highlight the importance of supporting students who face these self-regulatory demands in several ways. Advisors can be meaningful role models of tenacious behavior (Haimovitz & Dweck, 2017). By sharing some of their own work-related struggles (e.g., rejected research proposals) and modeling how to persist despite such setbacks, they might strengthen their students’ persistence. Supervisors should also keep in mind that positive feedback has a strong impact on beginners’ motivation (Finkelstein & Fishbach, 2012). While providing feedback to their students, PhD-advisors may thus not only focus on the things that could be improved, but also highlight positive aspects. These experiences could be helpful for newly beginning students to gain confidence in their abilities, which in turn could motivate them to put in more effort when confronted with obstacles. As other self-regulation strategies, frustration tolerance and delaying gratification cannot be exerted without commitment to a goal. Decreasing identification with a goal or perceiving goals as unattainable increases the likelihood of failure in self-regulation (Mackey & Perrewé, 2014). Thus, advisors can also help students setting realistic goals and rearranging priorities. In addition, social support may have an impact on self-regulation as it helps replenish depleted resources (Mackey & Perrewé, 2014). Remarkably, giving advice to others was shown to motivate academic achievement even more than receiving advice (Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2018). Therefore, it can be beneficial for students to engage in peer-to-peer support or even be advised to mentor a new doctoral student. Since cooperation elicits motivation to show delay of gratification (Koomen et al., 2020), collaborative work tasks and projects could be introduced more often.

Students should also learn to see good sleep as being relevant. In a study by Spaulding and Rockinson-Szapkiw (2012) many participants mentioned that they sacrificed sleep during their doctoral studies in order to manage the multiple demands. But research has shown that sleep deprivation reduces frustration tolerance and the ability to delay gratification (e.g., Kahn-Greene et al., 2006; Killgore et al., 2008). Similarly, Goldschmied et al. (2015) found that participants who took a 60-min nap showed increased tolerance for frustration on an unsolvable task and reported feeling less impulsive compared to participants in the no-nap condition.

In summary, our research contributes to the understanding of volitional demands and abilities for the PhD-process. Based on three studies, we found evidence that frustration tolerance and delay of gratification might be important for PhD-intention and experiencing success in goal pursuit. Creating a PhD-process excluding phases of setback and other stressors appears barely realistic. However, given the malleability of self-control, there are a number of starting points at which to strengthen these important abilities before and during graduate school.

Notes

-

Vignette descriptions were pretested in a pilot study with 98 psychology undergraduates. After reading the vignette, participants answered four questions. The first two questions concerned delay of gratification (r = .38 − .59): 1. Do you think Lisa R. can wait for gratification? 2. Do you think she can put her own interests last? The next two questions concerned frustration tolerance (r = .68 − .70): 3. Do you think Lisa R. gets discouraged after failure (recoded)? 4. Do you think she reacts with frustration when difficulties occur (recoded)? Results indicated that in the condition “delay of gratification_high” participants rated the first two questions higher (M = 5.42, SD = 0.12) than in the condition “delay of gratification_low” (M = 2.63, SD = 0.10), t(91) = 22.01, p < .001. In the condition “frustration tolerance_low” participants rated the last two questions higher (M = 5.42, SD = 0.65) than in the condition “frustration tolerance_high” (M = 1.76, SD = 0.10), t(91) = 23.66, p < .001.

-

In Study 2, vignette descriptions were restricted to a female student. To ensure that the judgements were not influenced by the gender of the described student, we cross-validated the findings of Study 2 in a supplementary study using the same vignettes with the description of a male student. 182 participants (52% female, 67% postdocs) aged 25–60 years (M = 35.1, SD = 7.1) were randomly assigned to read the vignette and answered the same questions as in Study 2. The result pattern did not differ from Study 2.

References

Achtziger, A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2018). Motivation and volition in the course of action. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and action (3rd ed., pp. 485–527). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65094-4_12

Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114547952

Atzmüller, C., & Steiner, P. M. (2010). Experimental vignette studies in survey research methodology. European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 6(3), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000014

Bair, C. R., & Haworth, J. G. (2004). Doctoral student attrition and persistence: A meta-synthesis of research. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (pp. 481–534). Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2456-8_11

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bercovitz, J., & Feldman, M. (2008). Academic entrepreneurs: Organizational change at the individual level. Organization Science, 19(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0295

Bergey, B. W., Parrila, R. K., & Deacon, S. H. (2018). Understanding the academic motivations of students with a history of reading difficulty: An expectancy-value-cost approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 67(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.06.008

BMBF (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung). (2017). Bundesbericht zur Förderung des Wissenschaftlichen Nachwuchses (BuWiN) [Federal report about the promotion of young academics]. BMBF.

Brailsford, I. (2010). Motives and aspirations for doctoral study: Career, personal, and inter-personal factors in the decision to embark on a history PhD. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 5(1), 15–27.

Brandstätter, V., Heimbeck, D., Malzacher, J., & Frese, M. (2003). Goals need implementation intentions: The model of action phases tested in the applied setting of continuing education. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320344000011

Brislin, R., Lonner, W. J., & Thorndike, R. (1973). Cross-cultural research methods. Wiley.

Castro, V., Garcia, E. E., Cavazos, J., & Castro, A. Y. (2011). The road to doctoral success and beyond. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 6(1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.28945/1428

Corno, L. (1993). The best-laid plans: Modern conceptions of volition and educational research. Educational Researcher, 22(2), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X022002014

Cornwall, J., Mayland, E. C., van der Meer, J., Spronken-Smith, R. A., Tustin, C., & Blyth, P. (2019). Stressors in early-stage doctoral students. Studies in Continuing Education, 41(3), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1534821

Council of Graduate Schools. (2008). Ph.D. completion and attrition: Analysis of baseline program data from the Ph.D. completion project. Author.

Devos, C., Boudrenghien, G., Van der Linden, N., Azzi, A., Frenay, M., Galand, B., & Klein, O. (2017). Doctoral students’ experiences leading to completion or attrition: A matter of sense, progress and distress. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 32(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-016-0290-0

Ehrenberg, R. G. (2005). Involving undergraduates in research to encourage them to undertake Ph.D. study in economics. American Economic Review, 95(2), 184–188. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282805774669772

Eskreis-Winkler, L., Fishbach, A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2018). Dear Abby: Should I give advice or receive it? Psychological Science, 29(11), 1797–1806. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618795472

Finkelstein, S. R., & Fishbach, A. (2012). Tell me what I did wrong: Experts seek and respond to negative feedback. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(1), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1086/661934

Galla, B. M., & Duckworth, A. L. (2015). More than resisting temptation: Beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 508–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000026

Goldschmied, J. R., Cheng, P., Kemp, K., Caccamo, L., Roberts, J., & Deldin, P. J. (2015). Napping to modulate frustration and impulsivity: A pilot study. Personality and Individual Differences, 86(1), 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.06.013

Goller, M., & Harteis, C. (2014). Employing agency in academic settings: Doctoral students shaping their own experiences. In C. Harteis, A. Rausch, & J. Seifried (Eds.), Discourses on professional learning: On the boundary between learning and working (pp. 189–210). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7012-6_11

Groenvynck, H., Vandevelde, K., & Van Rossem, R. (2013). The Ph.D. track: Who succeeds, who drops out? Research Evaluation, 22(4), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvt010

Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2017). The origins of children’s growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88(6), 1849–1859. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12955

Heckhausen, H., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1987). Thought contents and cognitive functioning in motivational versus volitional states of mind. Motivation and Emotion, 11, 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992338

Hoerger, M., Quirk, S. W., & Weed, N. C. (2011). Development and validation of the Delaying Gratification Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 725–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023286

Kahn-Greene, E., Lipizzi, E. L., Conrad, A. K., Kamimori, G. H., & Killgore, W. D. S. (2006). Sleep deprivation adversely affects interpersonal responses to frustration. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(8), 1433–1443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.06.002

Kidd, C., Palmeri, H., & Aslin, R. N. (2013). Rational snacking: Young children’s decision-making on the marshmallow task is moderated by beliefs about environmental reliability. Cognition, 126(2), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.08.004

Killgore, W. D. S., Kahn-Greene, E., Lipizzi, E. L., Newman, R. A., Kamimori, G. H., & Balkin, T. J. (2008). Sleep deprivation reduces perceived emotional intelligence and constructive thinking skills. Sleep Medicine, 9(5), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2007.07.003

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford.

Koomen, R., Grueneisen, S., & Herrmann, E. (2020). Children delay gratification for cooperative ends. Psychological Science, 31(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619894205

Levecque, K., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., Van der Heyden, J., & Gisle, L. (2017). Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research Policy, 46(4), 868–879.

Litalien, D., & Guay, F. (2015). Dropout intentions in PhD studies: A comprehensive model based on interpersonal relationships and motivational resources. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41(1), 218–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.004

Lovitts, B. E. (2005). Being a good course-taker is not enough: A theoretical perspective on the transition to independent research. Studies in Higher Education, 30(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500043093

Lovitts, B. E. (2008). The transition to independent research: Who makes it, who doesn’t, and why. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(3), 296–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2008.11772100

Mackey, J. D., & Perrewe, P. L. (2014). The AAA (appraisals, attributions, adaptation) model of job stress: The critical role of self-regulation. Organizational Psychology Review, 4(3), 258–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386614525072

Martinsuo, M., & Turkulainen, V. (2011). Personal commitment, support and progress in doctoral studies. Studies in Higher Education, 36(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903469598

Meindl, P., Yu, A., Galla, B. M., Quirk, A., Haeck, C., Goyer, J. P., Lejuez, C. W., D’Mello, S. K., & Duckworth, A. L. (2019). A brief behavioral measure of frustration tolerance predicts academic achievement immediately and two years later. Emotion, 19(6), 1081–1092. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000492

Mischel, W. (1996). From good intentions to willpower. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognitions and motivation to behavior (pp. 197–218). Guilford.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Peake, P. (1988). The nature of adolescent competencies predicted by preschool delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.687

Mueller, E. F., Flickinger, M., & Dorner, V. (2015). Knowledge junkies or careerbuilders? A mixed-methods approach to exploring the determinants of students’ intention to earn a PhD. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.07.001

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Nerad, M. (2004). The PhD in the US: Criticisms, facts, and remedies. Higher Education Policy, 17(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300050

Owens, A., Brien, D. L., Ellison, L., & Batty, C. (2020). Student reflections on doctoral learning: Challenges and breakthroughs. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 11(1), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-04-2019-0048

Powell, K. (2015). The future of the postdoc. Nature, 520, 144–147. https://doi.org/10.1038/520144a

Roach, M., & Sauermann, H. (2010). A taste for science? PhD scientists’ academic orientation and self-selection into research careers in industry. Research Policy, 39(3), 422–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.004

Ruiz, D., Nava, C., & Carbajal, R. (2016). Issues in organizational assessment: The case of frustration tolerance measurement in Mexico. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, 10(3), 876–880. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1123630

Shoda, Y., Mischel, W., & Peake, P. (1990). Predicting adolescent cognitive and self-regulatory competencies from preschool delay of gratification: Identifying diagnostic conditions. Developmental Psychology, 26(6), 978–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.26.6.978

Silvia, P. J. (2019). How to write a lot: A practical guide to productive academic writing (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association.

Snow, R. E. (1989). Cognitive-conative aptitude interactions in learning. In R. Kanfer, P. L. Ackerman, & R. Cudeck (Eds.), Abilities, motivation, and methodology (pp. 435–473). Erlbaum.

Spaulding, L. S., & Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J. (2012). Hearing their voices: Factors doctoral candidates attribute to their persistence. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7(1), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.28945/1589

Steiner, P. M., Atzmüller, C., & Su, D. (2016). Designing valid and reliable vignette experiments for survey research: A case study on the fair gender income gap. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 7(2), 52–94. https://doi.org/10.2458/v7i2.20321

Sung, Y., Turner, S. L., & Kaewchinda, M. (2013). Career development skills, outcomes, and hope among college students. Journal of Career Development, 40(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845311431939

Van Rooij, E., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & Jansen, E. (2021). Factors that influence PhD candidates’ success: The importance of PhD project characteristics. Studies in Continuing Education, 43(1), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2019.1652158

Wao, H. O., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2011). A mixed research investigation of factors related to time to the doctorate in education. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 6(9), 115–134.

Warshaw, P. R., & Davis, F. D. (1985). Disentangling behavioral intention and behavioral expectation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 21(3), 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(85)90017-4

Wilde, J. (2012). The relationship between frustration intolerance and academic achievement in college. International Journal of Higher Education, 1(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v1n2p1

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Funding was provided by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Grant No. 16FWN009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Alisic, A., Wiese, B.S. How long can I wait and how much frustration can I stand? Volitional traits and students’ PhD-intention and pursuit. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 24, 99–123 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09543-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-022-09543-1