Abstract

Communication departments of international organizations (IOs) are important intermediaries of global governance who increasingly use social media to reach out to citizens directly. Social media pose new challenges for IO communication such as a highly competitive economy of attention and the fragmentation of the audiences driven by networked curation of content and selective exposure. In this context, communication departments have to make tough choices about what to communicate and how, aggravating inherent tensions between IO communication as comprehensive public information (aimed at institutional transparency)—and partisan political advocacy (aimed at normative change). If IO communication focuses on advocacy it might garner substantial resonance on social media. Such advocacy nevertheless fails to the extent that it fosters the polarized fragmentation of networked communication and undermines the credibility of IO communication as a source of trustworthy information across polarized “echo chambers.” The paper illustrates this argument through a content and social network analysis of Twitter communication on the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM). Remarkably, instead of facilitating cross-cluster communication (“building bridges”) Twitter handles run by the United Nations Department of Global Communications (UNDGC) seem to have substantially fostered ideological fragmentation (“digging the trench”) by their way of partisan retweeting, mentioning, and (hash)tagging.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Major international organizations (IOs) like the United Nations (UN), the World Health Organization, or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations must nowadays communicate to a strikingly complex and assertive societal environment (Bexell et al., 2021; Copelovitch & Pevehouse, 2019; Dingwerth et al., 2019; Tallberg & Zürn, 2019). Most of these IOs faced successive waves of politicization for decades, repeatedly making their authority and its legitimation a salient topic of progressive activism calling for the more effective protection of human rights or the environment as well as fostering global justice and public accountability (O’Brien et al., 2000; della Porta, 2007; Zürn et al., 2012). Recent iterations of politicization suggest a new spin on questioning IOs’ legitimacy as linchpins of such progressive “globalism,” making IOs powerful symbols on both sides of a deepening cleavage between cosmopolitan (or “liberal”) and anti-cosmopolitan (or “anti-liberal”) orientations (Hooghe et al., 2019b; Kriesi et al., 2008; Norris & Inglehart, 2019; Strijbis et al., 2018). In this context, IOs increasingly employ social media platforms such as Facebook or X/TwitterFootnote 1 to reach out to citizens directly (Bjola & Zaiotti, 2020; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020a). These platforms have important advantages for political communication but, at the same time, pose new challenges such as a highly competitive economy of attention and the fragmentation of audiences driven by networked curation of content and selective exposure (Barberá & Zeitzoff, 2017; Conover et al., 2011; Garrett, 2009; Hall et al., 2020; Klinger & Svensson, 2015; Meraz & Papacharissi, 2013; Williams et al., 2015). As a consequence, IOs on social media have to make tough choices about what to communicate and how.

According to the main argument developed in this paper, structural features of social media set strong incentives for IOs to privilege political advocacy—for example, to promote cosmopolitan issues such as human rights or sustainable development—over transparency-focused public information about institutional processes and operations. Such choices have substantial repercussions on how individual users receive IO social media communication as well as the overall topology of networked communication that results from such action. IO advocacy garners substantial resonance on social media, making it a central voice of the respective debate online. However, such advocacy tends to fail by successfully reaching only the already like-minded part of the usership while simultaneously further turning away the skeptics. Thus, IO advocacy on social media substantially fuels an already problematic process of fragmentation along ideological divides (“digging the trench”) instead of furthering exchange and consensus across camps and cleavages (“building bridges”). This suggests that IO advocacy can substantially aggravate widely noted problems of organizational delegitimation and what has been termed a crisis of the “liberal international order” (Adler-Nissen & Zarakol, 2020; Hooghe et al., 2019b; Ikenberry, 2010; Zürn et al., 2012). It can further undermine the credibility of IOs as sources of trustworthy information—a worrying consequence of advocacy in times of post-truth, in which shared understandings of global problems across camps are in short supply (Adler & Drieschova, 2021).

This paper illustrates the plausibility of the argument through an analysis of X/Twitter’s networked communication on the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM)—a non-binding international document that was approved by 164 countries on 10 December 2018 in Morocco and endorsed by the UN General Assembly about a week later. The GCM takes a cosmopolitan approach to migration that frames it as beneficial for all if well managed globally, but also as potentially dangerous—especially for vulnerable migrants—if it is not. In line with this approach, the GCM stresses the human rights obligations of states, and the need to confront xenophobia and expand legal pathways of migration (Guild et al., 2019; Nyers, 2019; Pécoud, 2021). The process that led to the GCM proved to be highly controversial as negotiations were accompanied by heated debates in parliaments and the general public. A legion of right-wing politicians and movement activists mobilized against the GCM at the local, national, and transnational level, for example, by spreading concerns about the GCM inviting mass migration while weakening sovereign control over national borders so desperately needed to protect own societies from what was said to be coming (Badell, 2021; Conrad, 2021; Müller & Gebauer, 2021). Along the way, several right-leaning governments decided to withdraw from the negotiations—including, among others, the United States, Australia, Austria, and Hungary.

Regarding this online debate, this paper pursues an ecological approach, taking into account not only how the UN communicated the GCM on X/Twitter but also how this communication resonated with an audience that actively curated the spread of UN messaging using retweets, mentions, and hashtags. Methodologically, it combines qualitative content analysis with supervised machine learning and social-network analyses of X/Twitter communication. Results suggest that the UN Secretariate sent a clear message of advocacy for a GCM by way of tweeting, retweeting, mentioning, and (hash)tagging. Other users responded in kind by treating the UN Secretariat as an advocate. Like-minded users widely shared its content, frequently mentioned UN official accounts, and used the UN main hashtag #ForMigration to self-identify as advocates. In contrast, critics carefully avoided any reference to UN communication in what was shared, who was mentioned, and which hashtags were used. As a consequence, two polarized clusters of like-minded communication evolved on X/Twitter, with UN accounts holding a central position in the advocates’ cluster but failing to reach those critical of the GCM as well as migration and the UN in general. Remarkably, instead of facilitating cross-cluster communication (“building bridges”) UN communication on X/Twitter thus seems to have fostered the formation of clusters (“digging the trench”), raising important questions of what role IO public communication can and should play in the face of a deepening rift of “cosmopolitan” versus “anti-cosmopolitan” politicization of global migration governance and beyond.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Part 2 provides a brief discussion of recent research on IO public communication and develops my argument concerning its use of social media and suggested problems of polarized fragmentation. Part 3 provides details on the GCM and the selection and coding of related tweets. Part 4 presents the results of the GCM case study before a brief conclusion summarizes and discusses these results.

2 The general argument: IOs, social media, and fragmentation

2.1 IO public communication in the digital age

IOs increasingly rely on digital means of communication to reach out to a broader audience (Bjola & Zaiotti, 2020; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020a; Hofferberth, 2020). Most of them now extensively use social media such as Facebook, Weibo, Instagram, or X/Twitter for disseminating a variety of information about, for example, speeches of organizational leaders, symposia of affiliated experts, the meetings and decisions of intergovernmental bodies, or the launch of major policy programs. What is more, they share related content provided by other organizations such as like-minded advocacy groups or member states’ governments. This process is part and parcel of a broader trend to more ambitiously communicate with nonstate audiences (Dingwerth et al., 2019). Over the last decades, IOs have codified public communication as an organizational task, departmentalized this task into well-staffed departments, and finally intensified strategic planning of public communication as indicated by the release of a multitude of strategy documents. Communication professionals inhabiting these bureaucratic spaces target a widening array of audiences—such as journalists, experts, advocacy organizations, corporate lobbies, and citizens—and have diversified communication channels to reach them, including social media (Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2018a).

Thus, public communication has arguably become a very important intermediary practice of current international governance. It bridges “structural holes” between the “inside” of international negotiations and policy programming with the “outside” of domestic as well as transnational publics in its organizational environment (Burt, 2005). Amongst nonstate actors and experts (Steffek et al., 2008), this makes communication departments powerful “brokers” (Burt, 2005) of information inside-out, which can have a substantial impact on how the public perceives and evaluates organizations’ mandates, procedures, and operations.Footnote 2 In this way, public communication may arguably play a key role in facilitating public control if approaching a mode of transparency-enhancing “public information” (Brüggemann, 2010): If informing the public about what an IO is and does, communication departments may effectively level information asymmetries, thus making the respective IO (and those actors working in their machinery) more accountable to all those affected by their talk, decisions, and action (Buchanan & Keohane, 2006). What is more, in cases of internal conflicts among stakeholders about procedures or policies, transparency-enhancing public information, by definition, should include balanced accounts of such conflicts and give voice to alternative perspectives on such issues.

Empirical evidence indeed suggests that a great deal of the long-term trend of IOs to enhance public communication can be attributed to changing norms of legitimate global governance that value institutional transparency as a precondition for public accountability (Dingwerth et al., 2019; Grigorescu, 2007). For example, mandates of major communication departments often frame the task as “public information” (Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2018a). In explaining its decision to establish its Department of Public Information (DPI) in 1946, the UN General Assembly started by acknowledging that the “United Nations cannot achieve the purposes for which it has been created unless the peoples of the world are fully informed of its aims and activities” (United Nations (1946), Annex I, para. 2.). In this spirit, the General Assembly approved “the press and other existing agencies of information [being] given the fullest possible direct access to the activities and official documentation of the Organization.” Consequently, it also placed the DPI under the obligation to limit itself to “positive informational activities” and to eschew “propaganda.”

In a setting of widespread politicization and delegitimation, such an approach to public communication can be deemed a strategic imperative to some extent. IOs can seek social legitimacy by bringing their communication in line with societal expectations about proper institutional conduct, for example, by providing a constant flow of information about action and results. Indeed, moments of massive public delegitimation (by protests or scandals) explain a great deal of the timing of organizational enhancement of public communication and the adoption of new technologies such as social media (Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2018a, 2020a). At the same time, they may motivate biases in privileging information about successes over failures to protect the organization from reputational damage (Capelos & Wurzer, 2009; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020b; Christian, 2022).

However, much of IO public communication is not concerned with institutional transparency (or self-legitimation by molding public perception of successes and failures) but with political advocacy promoting social change. IOs are important “governors” of global politics, mandated to implement ambitious policy programs vis-à-vis nonstate actors (Avant et al., 2010). In this context, communication departments are often tasked with advocacy campaigns targeting citizens directly—e.g., for women’s rights, sustainable development, or sanitary standards (Alleyne, 2003; Coldevin, 2001; Servaes, 2007). Tellingly, quantitative evidence suggests that those IOs active in the respective areas are more prone to adopt and use social media as new channels of public communication (Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020a). This also applies to the UN, where the Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications has recently called social media “a key” for a strategy shift towards “cause communications” whereby the aim is “not just to inform, but also to inspire people to care and to mobilize them for action” (United Nations, 2021: 3, 33). Consequently, the UN Social Media Team is located at the Communications Campaigns Service to “strengthen the full integration and the effective use of flagship social media platforms in various UN campaigns on priority themes” (United Nations, 2021: 3).

Notably, IO advocacy plays an essential role in terms of organizational self-legitimation (Gronau & Schmidtke, 2016). IOs are widely held to gain legitimacy as “community organizations” representing shared values (Abbott & Snidal, 1998). By advocating for social change, an IO may find wide recognition as a “moral authority” if such efforts credibly serve the normative aspirations of its audience (Barnett & Finnemore, 2004). As impartial guardians of the greater good, IOs gain autonomy vis-à-vis member states and enhance their chances to induce deference by powerful states. Nevertheless—and despite often claiming the opposite—much of IO advocacy is highly political in nature (Barnett & Finnemore, 2005: 174f; Avant et al., 2010: 18ff). Definitions of “shared values” or “principles” in global cooperation almost inevitably raise questions as to what extent they are truly shared (or even universal) or whether there are at least alternative readings of their implications (Ignatieff & Appiah, 2003). In the face of increased ideological polarization in Western societies, IO public communication regularly appeals to a cosmopolitan (or “liberal”) discourse that is notoriously contested by right-wing populist forces and treated with suspicion by its followership (Copelovitch & Pevehouse, 2019; Kriesi et al., 2008; Norris & Inglehart, 2019; Strijbis et al., 2018). Thus, to the extent that IOs become identified with cosmopolitan norms and values, their advocacy makes them powerful symbols on both sides of the divide. While skeptics seem to take IO advocacy as final proof of hostile intent, IO advocacy substantially enhances its moral authority vis-à-vis the like-minded parts of the audience.

If this reading is correct, public information and advocacy constitute, to some extent, alternative imperatives of IO public communication that might increasingly be hard to reconcile because of their problematic coupling with a third one, self-legitimation. In the context of widespread ideological polarization, IOs can play an eminent role as credible sources of problem knowledge across ideological divides as well as impartial facilitators to negotiate and implement joint action to solve such problems. However, the public recognition of IOs as trustworthy guardians of the greater good can suffer to the degree that IOs gain a public profile as partisan advocates of contested norms and values. As a consequence, advocacy could substantially undermine their credentials as sources of “public information” as well as their legitimacy as facilitators of joint action (at least for all those not cherishing what the respective IOs advocate for).

2.2 Social media and the temptation to privilege political advocacy

The extended use of social media by IO communication departments suggests new possibilities for pursuing public communication in several ways, including those broadly captured by a dichotomy juxtaposing “public information” and “political advocacy” as ideal types. A turn towards social media communication is all the more striking as digital spheres are deemed hotbeds of ideological polarization, which have arguably aggravated processes of IO delegitimation and stalemate over recent years (Adler & Drieschova, 2021; Adler-Nissen & Zarakol, 2020). So, how does social media afford or constrain public communication of IOs?

To start with, the more IOs develop direct channels, the more we should expect citizens to experience IOs as autonomous voices. Empirical evidence indeed suggests that several IOs have been surprisingly successful in gaining a central position on online communication networks, for example, in the case of global climate governance (Goritz et al., 2020). However, such centrality is far from inevitable and deserves a closer look. The reasons for this are at the core of networked communication: On social media, communication goes “many-to-many” and is largely based on a logic of virality in terms of a “network-enhanced word of mouth” (Klinger & Svensson, 2015: 1248). Shared meaning emerges through a crowd-driven process of networked agenda-setting and framing, which gives “the crowd” much more discursive power to curate and contest messages as well as to appropriate their meaning (Adler-Nissen et al., 2020; Hall et al., 2020; Meraz & Papacharissi, 2013). At the same time, the production of content is cheap; hence, networks are characterized by an abundance of voices and viewpoints, making attention a scarce resource. Relatedly, IO communication also faces a substantial share of “Digital Natives” on social media, which are said to gravitate “toward ‘shallow’ information processing behaviors characterized by rapid attention shifting and reduced deliberations” (Loh & Kanai, 2016: 507). For such an audience, new content typically pops up as “ambient” information at the periphery of users’ awareness (Hermida, 2010), thus rewarding extreme behavior and opinions at the expense of more moderate voices (Tufekci, 2017: 270ff).

To complicate things further, social media typically afford the communication of various kinds of content—including text, images, and audio—but put substantial constraints on how much is packed into the message as such. X/Twitter is an obvious case in point: with a maximal length of 280 characters, tweets are “structurally ill-equipped to handle complex content” (Ott, 2017: 61). Empirical evidence suggests that tweet length substantially constrains users from providing evidence for political claims as well as to foster impoliteness and even incivility to give tweets meaning at all (Oz et al., 2018). The relaxation of this constraint from 140 to 280 characters in late 2017—as well as similar adaption like no longer counting in certain components such as links and mentions—has arguably increased the deliberative quality to some extent; still, “brevity” remains the “the soul of Twitter” (Jaidka et al., 2019: 1). Strikingly, much of the political communication taking place on social media is linking external content to overcome such constraints (Jakob, 2022). But even then, communicators arguably face tough choices of which bits of information are to be highlighted in the individual communication to attract attention toward what is linked.

Regarding IOs, this suggests a remarkable ambiguity in using social media as a channel for comprehensive public information. Social media incentivize IO communication practitioners to translate international diplomacy into a more accessible and pointed language (Bouchard, 2020; Servaes, 2007), which might effectively enhance public accountability of IOs to some important degree. However, classical outputs of communication departments include press releases that often lay out in detail what officials have to say about major decisions, who has spoken about what in major plenary meetings, or the many issues an expert report has raised on certain policy matters. Such complexity cannot simply be “translated” into micro-messages such as tweets or posts but implies that content has to be massively cut, simplified, and (re)framed in a way that makes what is left meaningful at all.

Compared to public information, social media is arguably much more suitable for advocacy campaigns as its platforms are widely held to “invite affective attunement, support affective investment, and propagate affectively charged expression” (Papacharissi, 2016: 308; Hansen et al., 2011; Veltri & Atanasova, 2017; Adler-Nissen et al., 2020; Hall et al., 2020). Hence, networked communication is the medium of choice for political advocacy that employs emotive language and symbols to evoke the compassion of its target audience (Adler-Nissen et al., 2020; Hall, 2019). Instructively, the current usage of digital communication by larger IOs such as the UN suggests a privileged targeting of an audience that is hoped to empathically connect with a moral cause such as humanitarian aid, human rights, or sustainable development (Bouchard, 2020; Hofferberth, 2020; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2023). In terms of a first hypothesis, we should thus expect to find IOs to more generally privilege advocacy over public information in their social media communication.

2.3 Social media and the peril of polarized fragmentation

If this conjecture holds, however, IO advocacy on social media can be expected to fuel an often-lamented aporia of networked communication, particularly if what IOs advocate for is tied to greater political controversies: polarized fragmentation. A basic reason for this is the demand for filtering on social media. The aforementioned abundance of content suggests a necessity to individually control what is consumed as well as a need to be selective to handle problems of “information overload” (Schmitt et al., 2018). In such a context, users tend toward “selective exposure,” that is, to privilege content that confirms their pre-existing attitudes while avoiding dissonant information to some significant degree (Garrett, 2009). Personalization algorithms suggesting content, followers, and “trending hashtags” have been found to notoriously aggravate such privileged exposure to like-minded content (Flaxman et al., 2016; Hannak et al., 2013).

Much of the earlier literature uncritically assumes that both kinds of “filtering” foster the fragmentation of communicative ties and even include prominent warnings of highly self-referential “echo chambers” (Sunstein, 2007: 11) or “filter bubbles” (Pariser, 2011). Empirical studies have found fragmentation into homophile communities of like-minded users to exist to some extent, such as in the case of electoral politics (Conover et al., 2011), climate change discourse (Williams et al., 2015), and gun control (Cinelli et al., 2021), while not as widespread as often assumed (Bruns, 2019; Ross Arguedas et al., 2022). Such fragmentation might be of particular relevance for the future of global governance because it could severely undermine the potential of rational and inclusive consensus on important issues such as climate change or international inequality—problems for which a solution cannot be conceived without strong global regimes based on a broad public consensus. For years, empirical descriptions of increasingly transnationalized communication (Peters et al., 2005) have been taken as promising hints to an emerging global public sphere (Volkmer, 2003) that could function as a building block of a global cosmopolitan order capable of legitimate as well as effective global policy making (cf. Hall, 2022). Against this backdrop, increasing fragmentation of communication can be expected to pose a significant challenge by aggravating the polarization of many societies into “cosmopolitans” and “anti-cosmopolitans,” thus narrowing the domestic window of opportunity for democratic governments to successfully negotiate a further delegation of competences at the international level (Kriesi et al., 2008; Norris & Inglehart, 2019; Strijbis et al., 2018).

Arguably, though, sensational warnings of the decentralized “power of complete filtering” (Sunstein, 2007: 11) in network communication are far too (techno-)deterministic (Bruns, 2019). Among other factors, a high-choice media environment not only facilitates selective exposure but also a diverse media diet across platforms, especially for those more interested in politics (Dubois & Blank, 2018). What is more, every use of social media comes with a substantial degree of “incidental exposure” (Boczkowski et al., 2018; Fletcher & Nielsen, 2018) to political information, for example, because selected content is, on average, sufficiently diverse in terms of alternative viewpoints (Flaxman et al., 2016; Garrett, 2009). News organizations active on social media still seem to play a positive role in bringing more diverse content to the attention of online users (Heiberger et al., 2022). Also, users’ social networks seem to be shaped by non-political interests such as family, sport, business, or local communities online as well as offline. Thus, mechanisms of selective exposure and personalized filtering might be effectively “counteracted by the sheer messiness of empirical reality” (Bruns, 2019: 116). But the most striking argument against a techno-deterministic account of fragmentation is the empowered user itself, as social media allows to promote or overcome fragmentation in various ways. A brief discussion of three key affordances of social media—sharing, mentions, and hashtags—may be in order to justify this claim:

To start with, “sharing” of messages is widely perceived as a most important affordance of social media platforms, offering new opportunities to “knit together” individual utterances and to “provide a valuable conversational infrastructure” (boyd et al., 2010: 7). As in many seemingly “technological” affordances, it started as a social practice of attributing content to others, which platforms later turned into “buttons” (Kooti et al., 2012). Such automatization of sharing has transformed messages into originals and countable copies, making respective counts a viable measure of “virality” that steers the attention of other users (Paßmann, 2019). Evidence suggests that sharing others’ messages can be perceived to signal support (Metaxas et al., 2015: 4; Goritz et al., 2020). However, many users now add disclaimers to clarify that sharing is not an endorsement. Also, users may send a ‘public reply’ if commenting on others’ content that is linked or cited (Das & Chakraborty, 2022; Garimella et al., 2016; Tufekci, 2014). Thus, social media allow users to work for or against homophile fragmentation by sharing others’ content: while they may choose to predominantly distribute like-minded content, they may equally try to feature alternative voices in a more balanced way to facilitate transparency, if not dialogue.

Second, most social media platforms also allow explicitly addressing other users, for example, by applying the @user-convention (mentions). Similar to other affordances of social media, mentions evolved in a co-evolutionary process of social conventions and technology (Halavais, 2014; Honeycutt & Herring, 2009). In terms of meaning, mentions are widely used in political campaigns to reaffirm allegiances to like-minded advocacy groups (Hemsley et al., 2018). Here, Liu and Xu have argued that relief agencies address a multitude of stakeholders during emergencies to “signal to the greater public or the third-party stakeholders about inter-organizational alliances, joint action commitment, or moral support” (Liu and Xu, 2019: 4922). In this way, mentioning also permits effective enhancement of the reach of messages to like-minded users. For example, activists and campaigners have strategically employed mentions of celebrities to garner cascades of retweets by their large followership (Tufekci, 2017: 56; Hemsley et al., 2018). At times, users nevertheless employ mentions as tools to reach across the aisle and directly address opponents in a political conflict. For example, mentions are regularly used to signal openness for conversation across candidates and play a remarkable role as a “simulacrum of interaction” on social media in times of elections (Hemsley et al., 2018).

Lastly, hashtags are another powerful feature of online discourse. As “discursive assemblages,” they combine both a meaningful term (“text”) with a searchable tag as metatext (Rambukkana, 2015: 3). Concerning the former, hashtags are employed as important “soft structures” of storytelling (Papacharissi, 2016) and tools for framing content (Meraz & Papacharissi, 2013). Concerning the latter, hashtags function as an “indexing system” (Xiong et al., 2019) on social media and constitute important vehicles of self-curated thematic content (Meraz, 2017). If employed, content becomes easier to search and identify by other users as a contribution to a specific conversation and facilitates “hashtag publics” (Rambukkana, 2015). Both—the quality as text as well as metatext—make them part and parcel of what has been termed “hashtag activism” where hashtags of high valence (e.g., #MeToo, #ClimateAction, #BuildTheWall) are used as a “primary channel to raise awareness of an issue and encourage debate via social media” (Tombleson & Wolf, 2017: 2). In this regard, political debates on social media seem to promote hashtags that are predominantly employed by like-minded users, thus fostering their recognition as ideological markers (e.g., #BlackLivesMatter vs. #AllLivesMatter) and, by implication, social fragmentation (Conover et al., 2011: 95). At the same time, however, hashtags can be employed to overcome an ideological rift. Located at the “macro-layer” of social media communication, they are prone to reach beyond established networks of followers (Bruns & Moe, 2014). By (ab)using “high-valence” hashtags, outsiders may even deliberately “hijack” (or “hashjack”) the selection routines of a segregated community to inject deviant content into its internal debate (Conover et al., 2011; Darius & Stephany, 2019; Tombleson & Wolf, 2017).

Thus, there is no place for techno-social determinism with regard to how users—including IOs—contribute to processes of polarized fragmentation through their tweets, sharing, mentions, or hashtags. Users have a choice to employ technical means in alternative ways—including those “digging trenches” as well as “building bridges.” This calls for a deeper look at the potential of IO communication for enhancing polarized fragmentation as well as overcoming it. By privileging like-minded voices and arguments, an advocatory approach to IO communication may effectively contribute to the virality of respective content and strengthen the public presence of like-minded voices. At the same time, IO advocacy sends a strong signal of partisanship to its environment, thus fostering the resonance of its advocatory content among like-minded voices, while turning away those users with alternative stances in the debate (my second hypothesis). If that is correct, we should find like-minded users to react to IO advocacy by substantially sharing its messages, mentioning its accounts, and using its hashtags. Still, we should also find skeptics doing the opposite, that is, carefully avoiding spreading IO messages in their networks, mentioning IO accounts, and using its advocatory hashtags.

As a result, we can expect such handling of IO advocacy to shape the overall topology of topical communication on social media in important ways. From what we know about the dynamics of social media, we can infer that IO advocacy should substantially contribute to the formation of self-referential clusters of polarized communication (“dig trenches,” my third hypothesis). Notably, an alternative approach of “public information” would be possible: IOs could keep a focus on non-advocatory information as well as use the aforementioned features of social media communication to enhance transparency by providing a balanced picture of alternative voices and arguments. Thus, an inclusive approach of “public information” could facilitate a perception of neutrality as well as pro-actively foster cross-cluster communication by way of sharing, mentioning, or hashtagging competing stances on the issue (“building bridges”)—which would arguably best serve normative demands for using communication to cognitively empower a broader audience and thus enhance public accountability (Brüggemann, 2010; Buchanan & Keohane, 2006; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020b). Nevertheless, if IOs indeed tend to privilege advocacy over public information in their social media communication, we should expect polarized fragmentation to be the more likely outcome.

3 Method of the GCM case study

To illustrate the plausibility of my general argument (and the related three conjectures), I focus on global migration governance, which has seen intensive and heated multilateral negotiations of the Global Compact for Migration (GCM) under the auspices of the UN. The GCM process started in early 2017 when UN member states agreed on the timeline for three phases of consultations, stocktaking, and final negotiations (Ferris & Donato, 2019: 100–122). Important responsibilities for this process were shared among several branches of the organization. The process was formally led by the President of the General Assembly, who named the ambassadors of Mexico and Switzerland as co-facilitators. The UN Secretary-General played his part by making Louise Arbour his “Special Representative for International Migration,” who was tasked to work with states and other stakeholders on the development of the Compact but also played an important role in the public advocacy for it. Finally, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) was heavily involved as well, for example, by organizing a series of national-level consultations (Bradley, 2020).

The process spurred public controversies and mobilized protests in many countries, including Sweden, Germany, Austria, Britain, and Belgium (Conrad, 2021), which have been heavily orchestrated by right-wing populist party leaders and affiliated media organizations (Rone, 2022). Public attention substantially grew after the US government announced its withdrawal from the process in fall 2017. In Europe, the withdrawal of the Austrian government from the GCM process in late 2018 made similar headlines and led to a domino effect among right-leaning governments in Hungary and the Czech Republic (Badell, 2021). The Belgian coalition government even collapsed over the issue right before final negotiations began at the Marrakech conference on 10 December 2018. The GCM process formally came to a close when the UN General Assembly endorsed the GCM through a resolution on 19 December 2018, which was supported by 152 countries, with 12 abstentions and the governments of the United States, Hungary, Israel, Czech Republic, and Poland voting against it.

By and large, the GCM process has been highly controversial, as an increasingly deep divide between cosmopolitan and anti-cosmopolitan voices has led to hardened dissensus on the future of international order at various levels. Universalist claims are at the core of the GCM: its approach focuses on “orderly and regular” migration as being to the benefit of all, i.e., migrants as well as home, transit, and host societies (Nyers, 2019; Pécoud, 2021). At the same time, it frames migrants as a vulnerable group that deserves special protection, given multiple threats such as trafficking, exploitation, and xenophobia. Such claims have been most fiercely contested by right-wing politicians and activists who denounce the GCM as a self-serving project of (liberal) elites (Müller & Gebauer, 2021). It has been accused of encouraging mass migration from all the “inferior” parts of the world as well as neglecting inherent distributional conflicts on territory, wealth, and culture to the detriment of national communities (Badell, 2021; Conrad, 2021; Rone, 2022). Despite the GCM not being legally binding, it has been widely described by its critics as an attempt to weaken sovereign control over national borders, which—from their perspective—are essential to protect their societies from the many dangers of irregular mass migration (ibid.). Thus, the GCM debate provides a prime case for how IOs have become linchpins of contestation of the “liberal international order” (Adler-Nissen & Zarakol, 2020; Hooghe et al., 2019b; Ikenberry, 2010; Zürn et al., 2012) in the recent past and how IO communication has been working in such a context.

I chose X/Twitter for a detailed discussion of GCM-related social media communication. X/Twitter is only one of many other social media platforms that differ significantly with regard to their specific features and audiences (Bossetta, 2018). In absolute numbers, it ranks only fourteen in terms of global usership (Kemp, 2023: 182), and most of its users reside in the US, Japan, India, and Brazil (Kemp, 2023: 294). But its reach is significant wherever internet penetration is high, and authorities have not tried to block access (such as in Russia and China). Compared to other platforms such as Facebook or Instagram, users turn to X/Twitter more for news and updates on current events than, for example, entertainment or keeping in touch with friends and family (Kemp, 2023: 188), suggesting that X/Twitter is more relevant for discussing its role in IO communication. Set up as a microblogging service at the beginning, X/Twitter has been appropriated for more interactive debating of political issues (Kooti et al., 2012). Consequently, it not only functions as a primary news source for many of its users but also as a conversational sphere that allows for the networked curation and negotiation of political meaning (Mitchell et al., 2012). The way practitioners employ its benefits for political campaigning seems to reflect this (Kreiss et al., 2018) as well as recent findings that indicate political communication on X/Twitter to be more polarized on average than on other platforms (Yarchi et al., 2021). Most importantly, a recent study suggests that about four out of five IOs had at least one active handle on X/Twitter in 2018, with most of them having several (Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020a). X/Twitter is also extensively used by the UN for “reaching a wide and diverse global audience” (United Nations, 2021: 16). Both make it a plausible case for investigating to what degree the UN can effectively reach out to a broader audience, while its specificities as a platform suggest some limitations in terms of the external validity of findings and possibilities for generalizing beyond the specific case.

Finally, I focus on the communication of the UN Secretariat. The Secretariat took the lead in the overall procedure of coordinating the GCM process, so the output of its central communication branch, the UN Department of Global Communication (UNDGC), deserves special attention for how the GCM was communicated. UNDGC is responsible for “communicating to the world the ideals and work of the United Nations; interacting and partnering with diverse audiences; and building support for the purposes and principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations” (United Nations, 2021: 4). With a total annual budget of about US $101 million in 2022 and 703 staff members (United Nations, 2021: 21), it must report annually to member states via the Committee on Information of the UN General Assembly, while the Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications at its helm directly reports to the Secretary-General regularly. At the same time, its Social Media Team (of about 23 staff members) has been responsible for 166 accounts on fourteen different social media platforms (in order of relevance: X/Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, LinkedIn, Flickr, Medium, Youku, Weibo, Tumblr, TikTok, WeChat, Snapchat, and Pinterest). To make this possible, staff from all branches of the UN contribute content that is coordinated, streamlined, and published by the Social Media Team (United Nations, 2021: 33). UNDGC has an impressive outreach into its digital environment. In 2020, it reported about 66 million page views across the multilingual UN News websites to the General Assembly (United Nations, 2021: 21). Its main English-language X/Twitter handle @UN had about 11.9 million followers by the end of 2018 (when the GCM was finalized), which had grown to more than 16.2 million by early 2023.

Examining the UNDGC’s digital communication calls for caution as to the degree of generalizability of results in relation to IOs in general; the UN is a unique case as a leading “general-purpose” IO (Hooghe et al., 2019a: 75ff) with global membership. Additionally, its communications branch looks back on decades of experience in political campaigning (Alleyne, 2003). At the same time, UNDGC is an acknowledged leader in adopting digital means for this purpose in the wider field of IOs (Bouchard, 2020; Groves, 2018; Hofferberth, 2020), which gives observations additional relevance for understanding how digital communication in this organizational field might develop in the future.

This analysis tests the degree to which the following observable implications are empirically supported by UNDGC tweets and how such communication was received by other users:

In line with my first hypothesis, we should expect UN communication to privilege advocacy for the GCM by predominantly tweeting and retweeting content that positively evaluates the GCM as well as by predominantly mentioning like-minded users. Alternatively, the analysis could find UN communication to privilege negative content, to largely avoid evaluative content altogether, or to pro-actively “build bridges” by sharing positive as well as negative stances from voices inside or outside the UN. While I assume the first alternative (negative advocacy) to be implausible, the latter two alternatives (avoidance of evaluative content, balanced reporting) would, in principle, both qualify as “public information,” while only the latter would most clearly match what I have highlighted as possibilities for pro-actively “building bridges.”

According to my second hypothesis, IO advocacy is expected to foster more resonance among like-minded voices, while inclusive “public information” will more likely cause resonance across alternative stances in the debate. Regarding GCM communication, the observable implication of this expectation is that other users tend to share UN tweets more if in line with their own stances than otherwise. Relatedly, the more the UN is advocating for (or against) the GCM, the more other advocates (or skeptics) should share UN tweets in the aggregate, while a more ambivalent or neutral stance of the UN on the GMC should correlate with more similar levels of sharing by advocates as well as skeptics.

According to my third hypothesis, IO advocacy is expected to contribute to the formation of self-referential clusters of polarized communication (“dig trenches”), while IO public information is expected to work against polarized fragmentation (“build bridges”). The observable implication is that UN advocacy for the GCM should be matched by a topology of online communication in which like-minded voices tend to cluster in terms of retweets, mentions, and hashtags, and UN accounts are located at the center of advocatory communication—suggesting a most prominent role in GCM-related advocacy in terms of active resonance by like-minded users.

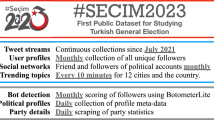

For investigating the degree to which empirical evidence indeed matches these implications, the analysis combines two sets of tweet data: (a) all GCM-related tweets of UN accounts centrally run by UNDGC (“Corpus 1”), and (b) all tweets related to the GCM process sent by these as well as other accounts but only for six selected days during major events of the GCM negotiation process (“Corpus 2”).

For Corpus 1, I relied on information provided by UNDGC about 23 X/Twitter handles directly run by the Department.Footnote 3 A complete list of these handles is provided in the Online Appendix available at The Review of International Organizations webpage. All original tweets (excluding retweets) posted by these handles between October 2016 and the end of 2019 in English were retrieved if containing the terms “pact,” “compact,” or “treaty” in combination with at least one of the terms “migrant,” “migrants,” “immigrants,” “immigrant,” “migration,” and “immigration.” After reading through all provided tweets a total of N = 270 tweets were identified as directly addressing the GCM.

For Corpus 2, I used purpose sampling for six important days along the GCM process, for which a minimal relevance of the topic—and, consequently, a high turnout—could be expected.Footnote 4 After a close inspection of UN communication online, the following six days were identified as most promising for analysis by maximizing (a) the number of tweets released per day and (b) a desirable spread over the course of the GCM process:

12 October 2017, the final thematic session “Irregular migration and regular pathways,”

4 December 2017, the first day of the stocktaking meeting,

13 July 2018, the release of a finalized draft of the GCM,

26 September 2018, the High-level event “Road to Marrakech,”

10 December 2018, states adopt the GCM on the international conference in Marrakesh,

19 December 2018, the UN General Assembly endorses the GCM (A/RES/73/195).

Again, all English tweets (including retweets) sent on these days were collected if containing the terms “pact,” “compact,” or “treaty” in combination with at least one of the terms “migrant,” “migrants,” “immigrants,” “immigrant,” “immigration,” and “migration.” The retrieval provided a total of N = 69,609 tweets fulfilling these criteria, of which 9925 (14.3%) are original tweets and 59,684 (85.7%) retweets.

In the next step, Corpus 1 (N = 270) of UNDGC tweets completely went into a qualitative content analysis with Atlas.ti. Additionally, a stratified random sample of Corpus 2 was drawn and coded as well. For this sample, all retweets of Corpus 2 were excluded to focus on non-redundant content. Then, the number of retweets per tweet (+ 1 to prevent tweets with no retweets from being dropped) was used as a sampling weight to account for the occurrence of similar text content in Corpus 2. A random sample (2000 picks with replacement) was drawn, resulting in a sample of N = 768 tweets. Due to the use of sampling weights, this sample is equivalent to a 31,528 sample (45.3%) of all items of Corpus 2 (N = 69,609).

The selected tweets of both corpora (N = 270 + 768) were manually coded regarding evaluative statements of one of the core aspects of the GCM debate on X/Twitter: the GCM itself, migration or migrants, multilateralism, and the UN (see Online Appendix, section A2 for details). To enhance the empirical basis, the analysis of Corpus 2 uses additional information provided by an automated classification of tweets. For this classification, the manually coded tweets in Corpus 2 were used to train two supervised machine-learning algorithms—one for detecting positive evaluations and one for negative evaluations—to predict the classification of the remaining tweets. Both models classified unlabeled tweets based on their similarity in word occurrences within the training data. Both were estimated with a linear Support Vector Machine with Class Weights (James et al., 2017: 337ff)—a non-probabilistic (binary) supervised learning classifier that is implemented in the Caret package in R and widely employed in similar research (Bozarth & Budak, 2021; Hemsley et al., 2018). Test statistics suggest an excellent performance of both classifiers (with Accuracy = 0.89 for negative content and 0.84 for positive content, respectively; see Online Appendix, Table A2 for alternative performance measures).

For the quantitative analysis, tweets and users have been classified the following way: A tweet coded with one or more positive evaluations is deemed “advocative,” in case of positive as well as negative evaluations classified as “mixed,” with only negative evaluations “critical,” and with not a single evaluation “neutral.”Footnote 5 Based on this classification of tweets, users have been classified according to the mode value of observed tweeting: users most frequently posting advocative content have been classified as “advocates” and those predominantly tweeting critical content “critics.” Moreover, I classified users as “ambivalent” if mostly tweeting mixed tweets or equally often advocative and critical tweets, and as “neutral” if most frequently posting non-evaluative content (see Online Appendix, section A6 and A7 for details and robustness of results applying alternative rules of classification).

Finally, the analysis operates with a classification of UN accounts in those (1) directly run by UNDGC, (2) a category of “Wider UN” accounts (N = 106) not directly run by UNDGC but belonging to other official branches or offices of the UN, and (3) all other accounts. A full list of accounts of the second category (“Wider UN”) is provided in the Online Appendix, section A5.

4 Results of the GCM case study

With regard to the GCM debate on X/Twitter, the following analysis provides ample evidence for three related conjectures in line with the general argument laid out above: First, UN social media communication was mainly advocative, thus sending a clear signal of partisanship to other users. Second, the UN was treated by other users accordingly, that is, as a partisan voice on the GCM. Content provided by UNDGC was widely shared by like-minded users, but was nevertheless mostly ignored by critics of international migration governance. Third, the overall structure of networked communication that resulted from this interaction shows the fragmentation of the GCM debate on X/Twitter into two segregated “bubbles”—a result substantially driven by the communication of UNDGC.

4.1 How UNDGC advocated for the GCM on X/Twitter

To start with, the UN Secretariat advocated for the GCM with regard to all four dimensions of X/Twitter communication addressed above: tweeting, retweeting, mentions, and hashtags. Regarding its own tweets, the relative frequencies of evaluative content of its tweets most clearly testify to the advocacy role that the UN Secretariat assumed in its X/Twitter communication. In almost every tweet (94.8%) authored by UNDGC one finds some evaluative content in terms of praising or positively framing issues at stake such as the GCM, migration, migrants, multilateralism, or the UN itself.

Most UNDGC tweets (91.1%) signaled endorsement of the GCM (or “Marrakech”), for example by calling the finalization of the treaty text a “historic moment” (@UN_News_Centre, 2018–07-13, 1017890484793020416)Footnote 6 and the Global Compact to be “grounded in principles of state sovereignty, responsibility-sharing, non-discrimination and human rights” (@UN_News_Centre, 2018–12-10, 1071953761365569538). More than half of all UNDGC tweets (52.2%) somehow addressed well-regulated migration in positive terms, while emphasizing the many dangers migrants face in unregulated migration.

“Migration has benefits for host and home countries alike. The Global Compact for Migration makes the most of these, while tackling the forced and irregular migration that carries high risks for migrants” (@antonioguterres, 2018-09-26, 1045044113207431168)

In this context, UNDGC tweets regularly referred to migration as an essential “part of our humanity” (@UN_PGA, 2017–11-28, 935472278917255168) and migrants (e.g., “children & youth on the move,” @UNDESA, 2018–06-22, 1010166442938036225) to have a legitimate claim for international protection. Furthermore, the GCM process is regularly framed as a prime example of successful international cooperation and multilateralism (in about 11% of all tweets, e.g., @louise_arbour, 2017–12-06, 938530540243832832). To some extent, the UN (or some of its staff or branches) praised itself (6.7%), for example, by claiming the GCM negotiations to prove that “#UNGA remains best place for states to address global issues & cross border challenges” (@UN_PGA, 2018–06-04, 1017890484793020416). In a few cases, positive references to “state sovereignty” as a core principle of the GCM (as in @UN_News_Centre, 2018–12-10, 1071953761365569538 cited above) can be interpreted as a strategic move to implicitly accommodate critics’ concerns regarding the legal implications of the GCM (explicitly addressed only once in @louise_arbour, 2018–01-23, 955806367557791744).

To grasp the visual quality of UNDGC advocacy, Fig. 1 provides a small selection of prominent tweets of UNDGC that nicely illustrate the use of pictures and videos as embedded content. While an in-depth analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, much of the imagery employed by UNDGC consists of “smiling migrants” and the UN as a forum of effective multilateralism, typically enriched with additional text along the lines of the overall messaging.

Remarkably, UNDGC only rarely tweeted without such positive evaluative content (4.8%), mainly to provide information about a scheduled press conference or the state of negotiations. To illustrate, one of these tweets informs users that “[a]head of Global Compact #ForMigration meeting in Morocco, UN Climate Conference #COP24 in Poland discusses recommendations for countries to cope with displacement of people as result of climate change” (@UN, 8 December 2018, 1071517776039227392). Tellingly, a critical evaluation is only reported in a single tweet on the final General Assembly vote (@UN_News_Centre, 2018–12-19, 1075487598116855808), which also communicated some member states’ dissent (coded as a “mixed” tweet because of reporting negative as well as positive evaluations). However, even in this case, support of the UN Secretariat for the GCM is explicitly articulated by adding that the Secretary-General calls its adoption a “key step to reduce chaos & suffering” (ibid.). Thus, no room is left for interpretation as to how the UN Secretariat positions itself vis-à-vis internal opposition.

Regarding retweets, accounts run by UNDGC exclusively shared content of other UN accounts—most of them being themselves run by UNDGC (58.3 percent), but also many of them run by other UN bodies or agencies (such as the IOM, UNFPA, and UNICEF, classified as “Wider UN,” see Online Appendix, Table A9 for details). As far as their tweets have been coded as well, none contained negative evaluations, suggesting that UNDGC deliberately focused on retweets as a means for advocacy (Fig. 2).

Evaluative tweet content by account type (in percent). Data varies across types of accounts to maximize precision: Numbers for non-UN Accounts (N = 9,753 tweets) and “Wider UN” (that is, UN accounts not run by UNDGC, N = 122 tweets) are based on all tweets included in Corpus 2 (partly coded automatically as described in the method section), while entries for UNDGC (N = 270 tweets) are taken from the full collection of UNDGC tweets (Corpus 1, manually coded)

Similarly, UNDGC used mentions mostly to feature its own accounts (63.1%) and less frequently to refer to other UN accounts (26.1%), while references to other handles were the exception (see Online Appendix, Table A10). To the extent that these other UN accounts sent tweets on the GCM that have been selected and coded as part of Corpus 2 (N = 122), all of them show a clear profile of advocacy for the GCM. This suggests that UNDGC effectively used mentions to support (and strengthen ties with) other parts of the GCM advocacy network, not to reach out to critics or those being ambivalent.

Finally, UNDGC used several hashtags to refer to the overall process of negotiating a Global Compact, including #migration or #GCM. However, it started early to keep a strong focus on #ForMigration (other UN accounts even more than those run by UNDGC, with 73.8% compared to 64.0%; see Online Appendix, Tables A11 and A12). This choice is important: While #migration and #GCM suggest being widely read as neutral “topic markers” in terms of substance, #ForMigration articulates a strong claim to advocate for migration as something good and worthy (instead of a problem to be solved as such). To conclude, UN communication as run by UNDGC or elsewhere in the organization shows a distinctive profile of advocacy for the GCM, narrating it as a cosmopolitan project fostering shared interests of all those involved as well as core values of the UN system (such as human rights) through international cooperation.

4.2 How UNDGC advocacy resonated with the like-minded (only)

UN advocacy took place in the context of a highly polarized debate on X/Twitter: About half of the tweets sent by non-UN users (55.5%) can be classified as “critical,” and only about one-fourth (23.3%) as “advocative” (Fig. 2). In fact, the most viral tweets in the sample include one sent by Fox’s anchorman Lou Dobbs on 4 December 2017, praising Donald Trump for leaving the GCM process with heralding “#AmericaFirst More than a Slogan for @realDonaldTrump as He Overrules Deputy, Pulls USA Out of U.N.’s Pro-Immigration Treaty” (@LouDobbs, 2017–12-04, 937553337918148608). On the same day, another tweet celebrating the withdrawal authored by @ScottPresler misleadingly adds: “No One Is Talking About This: Did you know that the UN used to control which migrants came to America?” (@ScottPresler, 2017–12-04, 2017937557502484451328). Throughout the GCM process, we find similar content that frames the GCM as an attempt by the UN to illegitimately force states to open borders for migrants. In many cases, migrants are targeted directly, too. For example, in one tweet @Eisdus calls the GCM an

“[o]rchestrated take down by the globalist institutions of western society thru mass influx of culturally incompatible unskilled poorly educated welfare bound migrants. Overloading of public services, cultural problems, societal conflict #resistglobalism #nationalism” (@Eisdus, 20 December 2018, 1075699061880225792).

Such blunt devaluations of the GCM, the UN, multilateralism, migrants, and migration overall are frequently articulated together, suggesting an attempt to integrate all these aspects in a “chain of equivalence” (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985) of “globalist” ills. In strong contrast, only a minority of tweets relate positively to the GCM process. By and large in line with UNDGC advocacy, such tweets cheer the overall project to address global migration governance in a comprehensive process of negotiations, reaffirm a shared responsibility to protect migrants from exploitation and abuse, or point to the overall societal benefits of migration.

To what extent did UNDGC advocacy resonate within this environment, especially with the more like-minded but not the critics (as expected in Hypothesis 2)? UNDGC accounts, first of all, substantially succeeded in triggering other users to share their content by retweeting it. About 6.7% of all retweets collected on the six selected days are shared tweets initially sent by UNDGC, and another 6.1% have retweeted content from other UN branches (see Online Appendix, Table A9).

This success might be partly attributed to an immense number of followers—@UN had more than 11 million in 2018 alone. But Fig. 3 also suggests that UNDGC advocacy overwhelmingly resonated with like-minded users, who used sharing as a means for online activism and “connective action” (Bennett & Segerberg, 2013). To illustrate, the selected tweets shown in Fig. 1 are also the three most-shared tweets of UNDGC—all in strong support of the GCM, which made retweeting them an act of advocacy itself. Not surprisingly, critics have carefully avoided sharing UNDGC content for not being associated with such advocacy. Consequently, they have also been hesitant toward “pinging” UN accounts directly by using the @mention-convention. While UN accounts are frequently mentioned overall (about 19.0% of UNDGC accounts plus 7.9% of other UN accounts, see Table A10), they are overwhelmingly addressed by like-minded users (with a share of 82.6% regarding UNDGC accounts). Thus, the evidence presented in Fig. 3 strongly supports the expectation formulated in Hypothesis 2, according to which UNDGC advocacy mostly resonated with the like-minded but not with the skeptics, who tended to avoid any direct reference to the UN.

The same holds true for the use of the UN hashtag #ForMigration. As argued above, the hashtag signals advocacy by deliberately supposing migration to be something positive per se. Usage by other participants in the GCM debate suggests a similar interpretation. Found in about 7.8% of GCM-related tweets overall (see Online Appendix, Table A12), #ForMigration is the most frequently used hashtag of the debate. However, as the data presented in Fig. 3 also indicates, the hashtag was almost exclusively (97.7%) used in tweets that articulated a positive stance towards the main issues at stake—the GCM, migration, the UN, and multilateralism. Thus, UNDGC succeeded in making its hashtag a main device for signaling a positive stance and an act of advocacy. At the same time, it made it fairly easy for other users to curate respective content along partisan lines, including efficiently avoiding UN communication entirely.

4.3 The topological outcome: polarized fragmentation

According to the general argument, a high degree of IO advocacy fosters critics’ avoidance of IO communication and thus nurtures the problematic fragmentation of political communication in, by and large, self-centric “bubbles” of homophile interaction (my third hypothesis). Does the GCM debate match this expectation?

To inspect the overall topology of the GCM debate on X/Twitter, information about retweeting and mentions were pooled in a dataset of directed links between user dyads indicating that a user has targeted another user by mentioning them or sharing some of their tweets by retweeting these at least once. Empirically, the collected data on GCM-related tweets and retweets allowed the construction of a data set of 57,327 directed “edges” between 38,574 users as “nodes.” The actual sum of retweets and mentions for each directed link between users varies from one to 24 (with a median of one) and went into the analysis as a weighting factor for respective “edges.” For the sake of simplicity, the visual analysis focuses on the largest connected (“giant”) component of this network and omits users that only target other users (by retweeting or mentioning them) without being targeted themselves (Fig. 3, see Online Appendix, section A9 for details).

First of all, visual inspection suggests a high level of segregation between two large areas of more intense interaction. While modularity analysis (Blondel et al., 2008) indicates several smaller communities inside these broader clusters (modularity score = 0.60 for 31 communities and a resolution set to 1), the overall topology is nevertheless dominated by a major divide. Remarkably, the UN main handle on X/Twitter @UN has the highest eigenvector-centrality score in the GCM network overall, indicating the most incoming ties (being retweeted or mentioned) and taking into account that such ties matter more if the sending nodes are themselves highly connected (that is central to the network in their own right). Thus, @UN is the most powerful hub of GCM-related communication overall. However, it is only effectively connected inside of the right-hand cluster, which is largely made up of UN accounts and all those users mentioning them or sharing their tweets, respectively (Fig. 4).

Polarized fragmentation in the GCM network. Graphical representation based on weighted data of retweets and mentions from Corpus 2. Nodes are only shown for those users (N = 1695) being mentioned or retweeted by at least one other user. Labels are given for the 20 most central accounts, with the size of labels and nodes reflecting the relative size of (eigenvector) centrality. In the digital version, the color of the edges reflects the ideological classification of the retweeted tweets, with blue indicating mostly advocative, red mostly critical, green mostly mixed or neutral (re)tweets and grey used for edges for which no information was available (about 38%). The size of the edges reflects the relative frequency of mentions and retweets for the respective pair of users. See the Online Appendix, section A9, for further details

The handle of the far-right media platform “Voice of Europe” (@V_of_Europe) is by far the most central for the left-hand cluster. Several other right-leaning accounts such as @BreitbartNews, @ScottPresler, @Lou Dobbs, @FiveRights (by alt-right author Philip Schuyler), or @PrisonPlanet (by Paul Joseph Watson, editor-at-large of Infowars.com) are of high centrality here. While the partisanship of the main nodes of the clusters already suggests polarization, we can turn to the specific content of tweets to verify this intuition right away. All edges of the network are colored based on the classification using supervised machine learning techniques (see method section and Online Appendix A4 and A9 for details and the digital version for a correct representation of colors). Strikingly, segregation in two major clusters largely overlaps with the ideological content of retweets and respective self-positioning of mentioned users, with advocacy for the GCM, migrants, migration, or the UN, defining the almost exclusively bluish cluster on the right-hand side—the “advocates’ bubble”—, and all that is contesting respective advocacy on the left—the almost entirely red-colored “critics’ bubble.” Thus, the overall structure of networked communication shows a high level of polarized fragmentation—a result that can partly be attributed to UN advocacy. While UN communication had an immense resonance on X/Twitter (with @UN being even the most central handle of the entire network), it failed to build bridges across the ideological rift.

5 Conclusions

Digital technologies, as such, have an immense potential for making IOs more publicly accessible, a potential almost all IOs have started to explore over the last decade (Bjola & Zaiotti, 2020; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020a). According to the general argument put forward in this paper, the trend of IOs to increasingly rely on social media suggests tough choices about what to communicate and how, aggravating inherent tensions of mandates to enhance institutional transparency (“public information”) and to campaign for social change (“political advocacy”). Competition for attention and virality sets problematic incentives for IO social media communication to privilege high-profile advocacy over low-profile public information (my first hypothesis). In case they choose advocacy, IOs garner substantial resonance on social media but nevertheless fail to the extent that they turn away critics (my second hypothesis). Advocacy thus fosters the polarized fragmentation of networked communication (my third hypothesis).

Evidence provided above indeed suggests that UN X/Twitter communication on the GCM took place in a highly fragmented network of homophile retweeting, mentioning, and (hash)tagging. In this context, UN messaging largely failed to reach critics of the GCM on related issues such as migration, migrants, multilateralism, or the UN. In line with my general argument, UN accounts arguably bolstered the divide by taking an advocative stance towards the GCM, retweeting and mentioning almost exclusively like-minded voices, and establishing the hashtag #ForMigration as a defining feature of its social media advocacy for the Compact. Thus, it was arguably predominantly “digging the trench” instead of “building bridges” toward its critics.

Such selective resonance of UN advocacy is instructive in the context of larger questions of legitimate international order and the role IO public communication is supposed to play therein. This sheds some light on a basic aporia of communicating international authority, which might be enhanced by ideological polarization: IO public communication has an eminent function as public information, which is supposed to neutrally inform about internal processes to make IOs transparent and accountable (Brüggemann, 2010; Dingwerth et al., 2019; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2018b). At the same time, IOs have been tasked with promoting norms and knowledge to the assumed benefit of societies, making IO public communication an important tool for spreading cosmopolitan ideas (Alleyne, 2003). Under the conditions of ideological polarization, both roles—providing public information and advocating social change—increasingly become undermined, if not contradictory. The more IO advocacy confirms critics’ expectations of the role IOs play in a clash of ideologies, the more any attempt to provide public information—about IO procedures, decisions, and policies—may be doomed to fail if critics do not consider the information provided by IO public communication to be credible.

Thus, what we see in the GCM case is striking: UN advocacy seems to have quite effectively drummed up the already like-minded but could also have added to its delegitimation because critics might have learned that the UN is partisan and thus not to be trusted—neither as a source of valid information about global migration flows, nor regarding what the GCM was actually about, nor that the UN works well as an accountable arena of fair and transparent international negotiations. In the long run, such advocacy could, therefore, do substantial harm to the projects it is advocating—as it has presumably done in the case of the GCM. It might aggravate widely noted problems of delegitimation as well as institutional failure. It could undermine the credibility of the UN as a source of trustworthy information, which is desperately needed to establish a shared definition of global problems such as climate change or the structural sources of global inequalities. It may also weaken public recognition of the UN as a fair and inclusive forum despite its increasing willingness to define “the people” as a major (if secondary) legitimating constituency (Dingwerth et al., 2019).

A great deal of additional research is needed to investigate the extent to which such conclusions are empirically valid—regarding the chosen case as well as beyond, that is, in terms of a general process of advocacy-driven fragmentation. To start with, the focus has been on the UN, which is arguably a very special case in IO communication. As the most eminent global “general-purpose” IO (Hooghe et al., 2019a: 75ff), it has the strongest mandate to address global issues across policy fields, while it is equipped with one of the most capable public communication departments in this organizational field with a long historical record of political advocacy campaigns (Alleyne, 2003; Bouchard, 2020). At the same time, the analysis focused on migration governance and the GCM as a likely case of cosmopolitan advocacy as well as anti-cosmopolitan contestation. Thus, one should be cautious about the extent to which findings can be generalized to IO communication per se. Future studies on other IOs and topics will have to show whether there is a robust correlation between IO advocacy and its centrality in one “bubble” of like-minded users plus, by implication, a failure to reach its critics.

What is more, this study has focused on UN communication on X/Twitter, because IOs—including the UN—still tend to privilege it over other platforms (Bouchard, 2020; Ecker-Ehrhardt, 2020a; Groves, 2018). However, previous research has rightly pointed to the many differences between platforms regarding their technological features and usership (e.g., Bossetta, 2018), which arguably puts some limits on how much generalizable conclusions can be drawn from a single-platform study (Kreiss et al., 2018). For example, recent research points to X/Twitter being especially conducive to polarization; thus, future research on IO communication on other platforms might find a more moderate outcome than the one presented here (Yarchi et al., 2021). Additionally, the analysis has exclusively focused on English content, even though the GCM has been heavily contested in non-English-speaking societies, such as Austria, Belgium, and Hungary—offline as well as online (Badell, 2021; Conrad, 2021; Rone, 2022).

Interestingly, however, while the descriptive results match what we would expect (advocacy correlates with selective resonance and fragmentation), there is a dire need for further evidence to better understand the scope of such relationships as well as their causal mechanisms. If the UN had not been involved at all, would there have been a less polarized debate? How would the debate have evolved if the UN had indeed contributed to “bridge building” rather than “digging the trenches”? In more general terms, what are the causal conditions of IO communication having an impact at all? Can IO public information really cause fragmentation or effectively facilitate a wider reach across camps and positions? Intuition suggests that comparative case studies could provide important insights here. Nevertheless, a turn to more focused experiments on how alternative approaches to IO communication have traceable causal effects on audience perceptions and legitimacy beliefs might be in order as well (cf. Brutger et al., 2022; Dellmuth & Tallberg, 2020; Dür & Schlipphak, 2021). In both ways, the presented findings suggest that such research could greatly contribute to our understanding of the legitimation dynamics of international governance in the “global information age” (Simmons, 2011).

Data availability

Supplementary information (including all data and codes for replicating results) will be posted at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse after publication.

Notes

-

In July 2023, Twitter was rebranded to X. However, throughout the paper, I refer to the platform as "X/Twitter" to avoid confusing readers and emphasize continuities.

-

Notably, many communication departments of IOs are also tasked to span organizational boundaries outside-in, by systematic screening of target audiences to better understand public opinion as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of communication activities.

-

https://www.un.org/en/sections/about-website/un-social-media/index.html [accessed on 4 October 2022].

-

While purpose sampling had practical advantages, there are arguably two important drawbacks: First, the degree to which results can be generalized across days remains unclear. Second, the focus on days with GCM-related events at the UN-level might skew the picture towards content that is addressing the UN to some degree as well as the salience of UN tweets.

-

Note that several tweets reported evaluations by other actors—including tweets of UNDGC as well as news organizations such as CNN, Reuters, or The Hill. For the following analysis such evaluations have been included, because they played an important role in the debate (for example, negative evaluations of the GCM by the US administration were only reported by other actors, for instance, its final dissenting vote in the UN General Assembly).

-

All tweets are referenced by handle, date, and number. The original URL can be directly inferred by the form “https://twitter.com/<author>/status/<tweet-number>,” which makes it possible to retrieve the original tweet directly from X/Twitter or the Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org).

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (1998). Why States Act Through Formal International Organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32.

Adler, E., & Drieschova, A. (2021). The Epistemological Challenge of Truth Subversion to the Liberal International Order. International Organization, 75(2), 359–386.

Adler-Nissen, R., Andersen, K. E., & Hansen, L. (2020). Images, emotions, and international politics: The death of Alan Kurdi. Review of International Studies, 46(1), 75–95.

Adler-Nissen, R., & Zarakol, A. (2021). Struggles for recognition: The liberal international order and the merger of its discontents. International Organization, 75(2), 611–634.

Alleyne, M. D. (2003). Global Lies? Propaganda, the UN, and World Order. Palgrave Macmillan.

Avant, D. D., Finnemore, M., & Sell, S. K. (2010). Who Governs the Globe? In D. D. Avant, M. Finnemore, & S. K. Sell (Eds.), Who Governs the Globe? (pp. 1–35). Cambridge University Press.

Badell, D. (2021). The EU, migration and contestation: The UN Global Compact for migration, from consensus to dissensus. Global Affairs, 6(4–5), 347–362.

Barberá, P., & Zeitzoff, T. (2017). The new public address system: Why do world leaders adopt social media? International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 121–130.

Barnett, M. N., & Finnemore, M. (2004). Rules for the world: International organizations in global politics. Cornell University Press.

Barnett, M. N., & Finnemore, M. (2005). The Power of Liberal International Organizations. In M. N. Barnett & R. Duvall (Eds.), Power in Global Governance (pp. 161–184). Cambridge University Press.

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge University Press.

Bexell, M., Jönsson, K., & Stappert, N. (2021). Whose legitimacy beliefs count? Targeted audiences in global governance legitimation processes. Journal of International Relations and Development, 24(2), 483–508.

Bjola, C., & Zaiotti, R. (Eds.). (2020). Digital Diplomacy and International Organisations: Autonomy. Routledge.