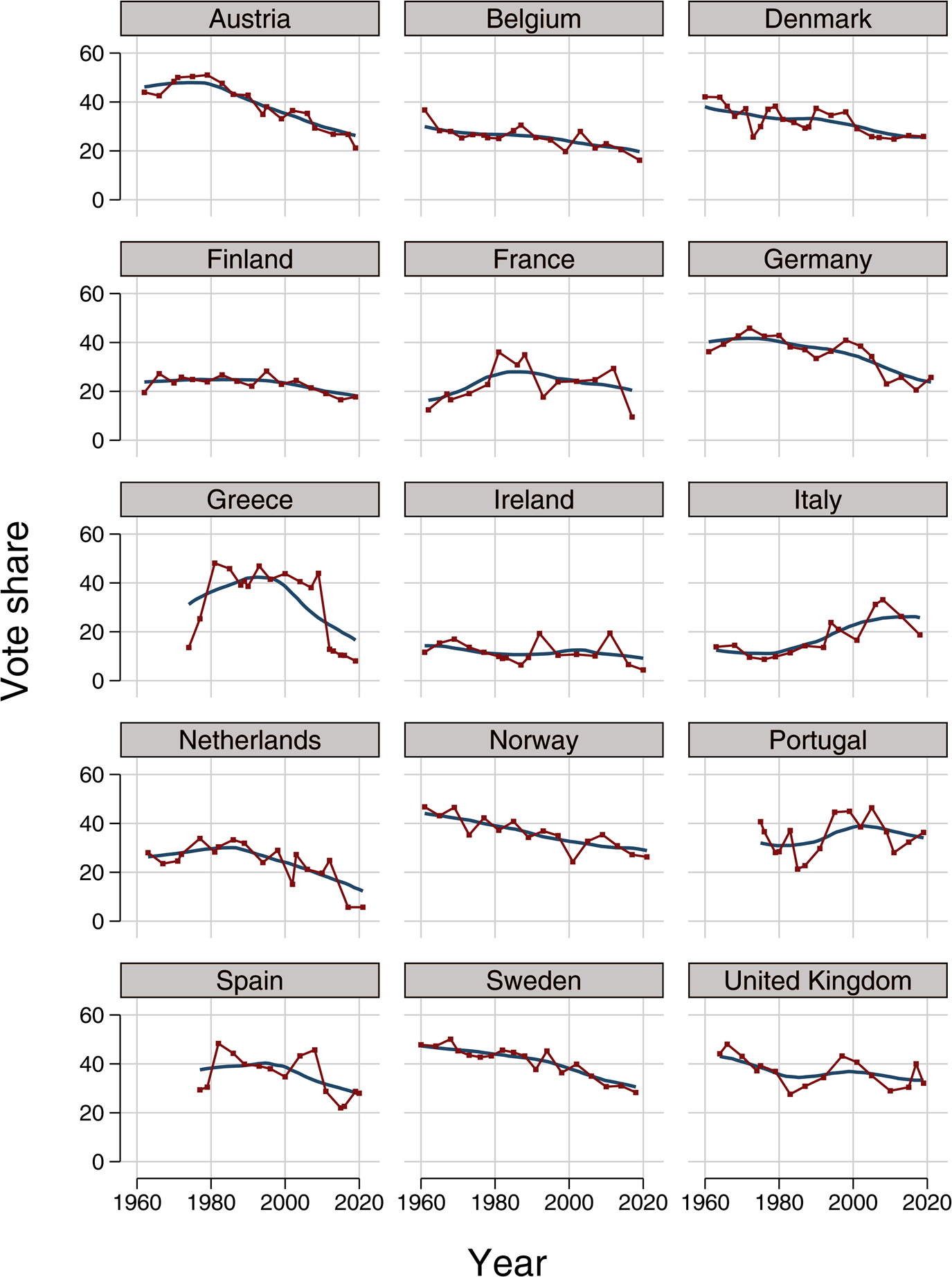

Despite some signs of life, such as the SPD's victory in the 2021 German federal election, social democracy in Western Europe has witnessed an electoral decline over the last decades, which has in many countries accelerated since the Great Recession (see Figure 1). Striking examples of the downturn are the Greek Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK, dropping from 43.9% in 2009 to 6.3% in 2015), the French Socialists, who have been fighting for political survival since missing the run-off in the 2017 presidential elections, and the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA, declining from 24.8% in 2012 to 5.7% in 2017 and 2021). The recent election victory of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), for its part, marked a surprising comeback from the historical nadir of 12% in the polls in 2019. The British Labour Party seemed to buck the trend under Jeremy Corbyn with an unexpectedly good result in the 2017 parliamentary elections but suffered its worst defeat since 1935 in terms of parliamentary seats in the ‘Brexit elections’ of 2019. One exception to the trend is the Portuguese Socialists, who, against all odds, were able to form a left-wing government in 2015, leading to remarkable electoral successes in 2019 and 2022.

Figure 1. Electoral Performance of Social Democrats in Western Europe, 1960–2021

While there is in light of those numbers unanimous agreement about the crisis of social democratic parties in Western Europe (see e.g. Benedetto et al. Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020; Manwaring and Kennedy Reference Manwaring and Kennedy2018; Mudge Reference Mudge2018; Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021; Sassoon Reference Sassoon2014), explanations for this development differ not only among social democratic politicians and political journalists but also among researchers. Depending on the author, the blame for the electoral crisis of social democracy is put on social democrats' ‘“tragic” competitive situation’ (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994: 34) in post-industrial societies, ‘the collapse of the postwar economic boom’ (Lavelle Reference Lavelle2008: 1), ‘the global freedom of capital’ (Gray Reference Gray1996: 17), ‘the economically neo-liberal and institutionally conservative European framework’ (Escalona and Vieira Reference Escalona, Vieira and Bailey2014: 23), ‘the Left's defensive strategy’ (Sassoon Reference Sassoon2014: xxi–xxii), the ‘cartelization’ of social democratic parties (Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019), their third ways' fatal failure to give a ‘meaningful voice to insecure, financially anxious, and downwardly mobile people’ (Mudge Reference Mudge2018: xv), or their lack of ‘attractive messages about how to solve contemporary problems’ as well as an ‘attractive vision of the future’ (Berman Reference Berman, Manwaring and Kennedy2018: 4). In other words, social democrats' amazement at their own decline is mirrored by researchers' disagreement on the causes of this decline.

Given the numerous, in parts conflicting, explanations, the first goal of this review article is to organize the literature in a sensible way. For this purpose, four kinds of explanation are distinguished: sociological, materialist, ideational and institutional. The second part of the article tests if the derived hypotheses are supported by empirical evidence. This test is based on 51 empirical studies published since 2010. The findings indicate that there is not one explanation that stands out but that the electoral crisis of social democracy is a complex phenomenon which has several causes, such as socio-structural changes, fiscal austerity and neoliberal depolarization.

The crisis of social democracy: four explanations

The authors cited above offer very different explanations for the crisis of social democracy, which range from structural changes in economy and society to organizational deficits and strategic errors on the part of social democrats. To systematize the literature, I mirror the work by Fernando Casal Bértoa and José Rama (Reference Casal Bértoa and Rama2020), who distinguish sociological, economic and institutional factors to explain the rise of anti-establishment parties. Adding ideational factors as a fourth category, I propose the following types of explanation for the electoral decline of social democracy: sociological explanations focus on socio-structural changes detrimental to social democrats, confronting them with painful electoral dilemmas. Materialist explanations emphasize economic restrictions that make it difficult for social democratic parties to pursue the policies favourable to their constituencies. Ideational explanations blame the crisis on the adoption of new ideas by party elites and the resulting programmatic shifts. Finally, institutional explanations focus on organizational changes that have contributed to the alienation of voters from social democratic parties.

Sociological: the crisis as a result of a changing social structure

The sociological approach is based on the assumption that parties' prospects of success are mainly determined by the given social structure and related voter preferences. Accordingly, the crisis of social democracy results first and foremost from socio-structural changes which have altered party competition to the disadvantage of social democrats. The literature highlights three forms of electoral dilemmas: (1) the well-known but sharpening ‘electoral dilemma of socialism’; (2) the dilemma of facing competing demands of fragmented occupational groups in post-industrial societies; and (3) the so-called ‘insider–outsider dilemma’ originating from opposing interests of different labour market groups.

In its classical form, this explanatory approach points to the shrinking of the working class, the traditional core constituency of social democratic parties, as the main driver of electoral decline (e.g. Dahrendorf Reference Dahrendorf1987; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1978). The seminal version of this argument is provided by Adam Przeworski and John Sprague (Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986). Accordingly, there is a general electoral trade-off for social democratic parties between the working class and the middle class, resulting in the so-called ‘dilemma of electoral socialism’. In their efforts to broaden their base by attracting middle-class voters, social democrats ‘erode exactly that ideology which is the source of their strength among voters’ (Przeworski and Sprague Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986: 55). In times of a shrinking working class, social democrats are more or less forced to turn towards middle-class voters at the cost of losing workers' support (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; for a nuanced account see Rennwald Reference Rennwald2020).

The most prominent variant of the sociological approach can be traced back to Herbert Kitschelt's (Reference Kitschelt1994) seminal work on the transformation of social democracy. Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt1994: 40–66) rejects the existence of a simple trade-off between working-class and middle-class voters. Social democrats are rather competing for different occupational groups whose preferences can be mapped in a two-dimensional political space, as those groups not only differ on socioeconomic but also on sociocultural issues (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994: 8–39; Oesch Reference Oesch2006). Due to the transformation from industrial to post-industrial society, the sociocultural axis is gaining importance; that is, value issues are complementing or even replacing economic issues and thus dividing the social democratic electorate (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2004). The electoral dilemma of socialism is replaced by different forms of electoral dilemmas:

Social democrats here face a double trade-off. First, by moving along the vertical libertarian–authoritarian dimension, social democrats must decide whether they will rely on traditional less educated blue collar, working class voters or more on highly educated white collar employees. … Social democrats also face a second trade-off within the working class itself, contingent upon their distributive economic stance. (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994: 32–33)

The resulting constellation of party competition is highly unfavourable to social democratic parties. While they compete with left liberal parties for the votes of the new middle classes, surging parties of the radical right are strong challengers when it comes to the votes of the traditional working class (e.g. Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi and Beramendi2015; Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt, Rehm and Beramendi2015; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). In this regard, the adoption of a pro-welfare stance by radical right parties – that is, their embrace of welfare chauvinism – poses a particular threat to social democrats, as it helps the former to present themselves as the ‘new workers’ parties' and to irrevocably rob the latter of their traditional electorate (Harteveld Reference Harteveld2016).

A final strand of the sociological approach focuses on splits in the labour market and the resulting insider–outsider dilemma (Bürgisser and Kurer Reference Bürgisser and Kurer2021; Rueda Reference Rueda2005, Reference Rueda2007; Schwander Reference Schwander2019a, Reference Schwander2019b). Here, too, workers are not seen as a homogeneous bloc but rather as divided into two groups: labour market insiders with secure employment and labour market outsiders, such as temporary workers, who are confronted with permanent job insecurity.Footnote 1 This divide, which is intensified by deindustrialization and globalization, leads to an insider–outsider dilemma for social democrats as labour market policies which are in the interest of insiders, such as strong employment protection for this segment of the workforce, are often detrimental to outsiders, and vice versa (Rueda Reference Rueda2005, Reference Rueda2007). Thus, if social democrats focus on insiders, outsiders react by vote abstention or voting for populist parties. If social democrats, instead, propose policies that benefit outsiders, they risk losing insiders to other competitors such as centre-right parties. In short, whoever profits from splits in the labour market, social democrats are presumably the ones to suffer electorally from the insider–outsider dilemma (for an overview of potential electoral implications see Schwander Reference Schwander2019b).

Materialist: the crisis as a result of changing economic conditions

The materialist approach to the crisis of social democracy claims that changes in capitalist economies limit the policy options available to social democratic parties and complicate or even prevent the pursuit of social democratic goals, such as securing social rights and combating inequality. This explanation is based on the assumption that the electoral success of social democrats primarily depends on certain economic and social policies – that is, policies that improve the material situation of their traditional core electorate. In this context, we can distinguish three processes which have been highlighted by political economists to explain the crisis of social democracy: (1) globalization; (2) European integration; and (3) the end of the Fordist/Keynesian growth model.

Since the early 1990s, numerous authors have identified economic globalization as a major constraint for social democratic parties (e.g. Boix Reference Boix1998; Giddens Reference Giddens1998; Glyn Reference Glyn and Glyn2001; Gray Reference Gray1996; Pierson Reference Pierson2001: 64–89). Accordingly, the socioeconomic policies at the heart of social democratic success in the golden age, Keynesian demand management plus welfare state expansion, are doomed to fail under conditions of globalization:

The social-democratic economic programme – most centrally, promoting full employment by stimulating investment through a policy of deficit financing – has ceased to be sustainable. … [T]he power of the international currency and bond markets is now sufficient to interdict any such expansionist policies. … It is no exaggeration to say that the global freedom of capital effectively demolishes the economic foundations of social democracy. (Gray Reference Gray1996: 17)

While the globalization of product markets is intensifying international competition among national economies, the deregulation of financial markets provides capital owners with a permanent exit option. As a result, traditional social democratic policy instruments such as progressive taxation and public demand management are no longer feasible due to adverse reactions by capital owners and international investors (Glyn Reference Glyn and Glyn2001; Hall Reference Hall and Schmidtke2002; Scharpf Reference Scharpf2000). Social democrats have been restricted to supply-side policies and, even worse, permanent austerity, thereby alienating voters dependent on the welfare state (Horn Reference Horn2021).Footnote 2

For social democratic parties in Europe, the institutional arrangements resulting from European integration are perceived as an additional constraint (e.g. Bailey et al. Reference Bailey2014; Holmes and Roder Reference Holmes and Roder2012; Moschonas Reference Moschonas and Callaghan2009; Ross Reference Ross, Cronin, Ross and Shoch2011; Scharpf Reference Scharpf2009). While globalization mainly affects the autonomy of nation states, European integration goes further by also curtailing their sovereignty through legal restrictions. First, the EU's and the European Monetary Union's (EMU) ordoliberal framework acts like a straitjacket for social democrats (Biebricher Reference Biebricher2018: 193–224; Escalona and Vieira Reference Escalona, Vieira and Bailey2014: 22–30; Streeck Reference Streeck2017: 97–164). The scope for expansive fiscal policies is restricted by means of the Maastricht convergence criteria, further tightened through the European Fiscal Compact. Second, the European Central Bank with its strong commitment to price stability ensures that EMU members are deprived of the option to pursue an expansionary monetary policy and to stimulate the economy through external devaluation, constraints that proved fatal for deficit countries in the euro crisis (De Grauwe Reference De Grauwe2013; Scharpf Reference Scharpf2011). Finally, social democrats suffer from the asymmetry between positive and negative integration (Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2009). While ‘integration through law’ driven by the European Commission and the European Court of Justice has a mainly liberalizing effect, the corrective positive integration, which is necessary to create the ‘social Europe’ regularly hailed by social democrats, usually fails due to conflicting national interests in the European Council. The EU has thus become a ‘liberalization machine’ (Streeck Reference Streeck2017: 103–110) which makes it more difficult, if not impossible, for social democratic parties to defend the interests of workers negatively affected by economic liberalization.

The third strand of the materialist approach, originating from regulation theory (cf. Boyer Reference Boyer1990), attributes the decline of social democratic parties neither to globalization nor to Europeanization but rather to a more general crisis of capitalism: the collapse of the Fordist/Keynesian growth model of the post-war decades. This argument is presented in its harshest form by Ashley Lavelle (Reference Lavelle2008), who sees the ‘death of social democracy’ as inevitable due to its dependence on the exceptionally high growth rates of the post-war years: ‘A return to low growth in the 1970s removed the economic base of social democracy … [and] the end of the boom rendered impossible the simultaneous pursuit of policies that reduced inequality and raised living standards and which did not undermine capital accumulation’ (Lavelle Reference Lavelle2008: 1, italics in original). Wolfgang Streeck (Reference Streeck2017) makes a similar argument by claiming that the compatibility of (social) democracy and capitalism was restricted to the exceptional situation of the post-war decades. Since then, social democratic parties in power have tried to reconcile the conflicting interests of citizens (social security) and international investors (profits). The socialization of debt in the wake of the financial crisis has shifted the already tilted balance of power even further in favour of capitalists. As a result, social democrats find themselves in a more or less hopeless position when condemned to govern.

Ideational: the crisis as the result of ideological failure

The third explanatory approach rejects purely materialistic explanations and emphasizes the impact of ideas. From this perspective, it is especially the adoption of neoliberal ideas by social democratic elites which led millions of workers to turn away from social democrats. Other authors highlight the additional embrace of cosmopolitan positions on sociocultural issues, such as European integration and migration, which resulted in a ‘progressive neoliberalism’ (Fraser Reference Fraser2017) out of touch with large parts of the working class.

According to ideational explanations, the crisis of social democracy does not originate from unfavourable circumstances but from the intellectual shortcomings of social democratic elites: ‘Upon close examination … the most significant obstacles to a social democratic revival turn out to come not from structural or environmental factors … but from intellectual fallacies and a loss of will on the part of the left itself’ (Berman Reference Berman2006: 210–211). Regarding intellectual fallacies, several authors perceive the initially hesitant, later on sometimes euphoric, adoption of neoliberal ideas as social democrats' original sin (e.g. Berman Reference Berman2006: 208–218; Blyth Reference Blyth2002; Hall Reference Hall2003; Hay Reference Hay1999; Moschonas Reference Moschonas2002; Mouffe Reference Mouffe2005; Mudge Reference Mudge2018). At the core of neoliberalism is the conviction that individualized, market-based competition is superior to other forms of organization (Mudge Reference Mudge2008: 705–707). In programmatic terms, this means strengthening private property rights and extending the market to all realms of society – that is, policies generally in favour of capital owners in distributive terms (Harvey Reference Harvey2005).

In contrast to their critics, social democrats perceived their ‘third ways’ as an alternative to neoliberalism (see e.g. Giddens Reference Giddens1998). However, empirical studies show that the programmes of social democratic parties have become increasingly permeated by the neoliberal ethos of competitiveness since the 1980s (Amable Reference Amable2011; Manwaring and Holloway Reference Manwaring and Holloway2022; Mudge Reference Mudge2011). The result is the emergence of a ‘social democratic variant of neo-liberalism’ (Hall Reference Hall2003), ‘neoliberalized social democracy’ (Mudge Reference Mudge2018) or ‘market social democracy’ (Nachtwey Reference Nachtwey2013). The argument is put forward in the most drastic way by Chantal Mouffe (Reference Mouffe2005, Reference Mouffe2019), according to whom social democracy, with its subordination to neoliberal hegemony, has lost the ability to present an attractive political alternative to the electorate. As voters realize that they have nothing to gain from this languid social democracy, they turn to more energetic populist parties on the left and the right. This trend accelerated substantially when social democratic governments clung to the neoliberal rulebook even after the global financial crisis (Blyth Reference Blyth2013: 132–177; Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019).

A second ideational explanation complements this economic turn to the right with a turn to cosmopolitanism and identity politics (Cuperus Reference Cuperus, Manwaring and Kennedy2018; Fraser Reference Fraser2017; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2019). More precisely, this argument comes in two forms. According to the first version, social democratic elites' turn to identity politics with the focus on the emancipation of women, LGTBQ groups, migrants and other minorities resulted in the neglect of the struggle for the preservation of social rights essential for workers, regardless of their ethnic background or sexual orientation (Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2019: 105–123; Lochocki Reference Lochocki2018). The second version of the argument goes further in pointing out that the ‘progressive neoliberalism’ hailed by ‘third way’ social democrats – combining the political fight for equal opportunities with strong individualism and a rather critical attitude towards the welfare state – is at odds with the more communitarian and welfare-friendly positions taken by most workers (Cuperus Reference Cuperus, Manwaring and Kennedy2018; Fraser Reference Fraser2017). In each case, it is not so much social cleavages or economic constraints but social democrats' ideological shifts that have led to voter estrangement (Moschonas Reference Moschonas2002: 120–122).

Institutional: the crisis as a result of organizational deficits

The final explanation focuses on party institutions to explain the crisis of social democracy. According to this approach, social democratic parties have undergone an organizational transformation from mass integration party to cartel party. This transformation, which is connected to the inadequate social representation of important voter groups within social democratic parties, has resulted in an electorally fatal convergence with mainstream parties of the right. The parallel decline of trade unions is supposed to have an additional negative impact on social democratic parties.

According to several party scholars, the mass integration parties of the past have turned into cartel parties (Blyth and Katz Reference Blyth and Katz2005; Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995, Reference Katz and Mair2009; Moschonas Reference Moschonas2002: 123–144). Echoing Robert Michels's Reference Michels(2001 [1915]) ‘iron law of oligarchy’, social democratic parties have thus over time turned from organizations representing their members and voters into governing agencies:

With the development of the cartel party, the goals of politics become self-referential, professional and technocratic, and what substantive inter-party competition remains becomes focused on the efficient and effective management of the polity. Competition between cartel parties focuses less on differences in policy and more … on the provision of spectacle, image and theatre. (Mair Reference Mair2013: 83)

While this transformation is not without problems for other mainstream parties, it is seen as particularly harmful for social democrats for three reasons. First, social democrats' success has always relied heavily on social democrats' ability to mobilize workers and related social groups under the banner of class struggle, social justice and other egalitarian principles (Moschonas Reference Moschonas2002; Sassoon Reference Sassoon2014). The technocratic nature of the cartel party quenches this vital energy, regardless of whether it comes from the working class or the new middle classes. Second, the participation in the cartel of established parties means collaboration with centre-right parties as well as shrinking policy polarization. The convergence among mainstream parties, in turn, is seen as one of the main reasons for voters abandoning these parties in favour of more radical challenger parties (Berman and Kundnani Reference Berman and Kundnani2021; Grant Reference Grant2021; Meguid Reference Meguid2007). Finally, political economists have argued that those problems have been aggravated by the fact that the party cartel mainly operates on the basis of the neoliberal ideas outlined above (Blyth Reference Blyth2003; Blyth and Katz Reference Blyth and Katz2005; Hopkin and Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019).

A final process that has to be taken into account is the weakening of trade unions, best illustrated by declining membership numbers. While this development can partly be attributed to socio-structural changes, the liberalization of labour market institutions in which social democrats participated has contributed to union decline (Baccaro and Howell Reference Baccaro and Howell2017; Streeck Reference Streeck2009). Driven by social democrats' attempts to broaden their voter base as well as unions' disappointment about social democratic policies, the traditionally close ties between social democrats and unions, once the ‘Siamese twins’ of the labour movement (Ebbinghaus Reference Ebbinghaus1995), have eroded, though there remain substantial differences across advanced democracies (Allern et al. Reference Allern, Aylott and Christiansen2007; Allern and Bale Reference Allern and Bale2017). Union decline can, however, come at a substantial electoral cost for social democrats, as strong unions are supposed to boost voter turnout among the working class as well as support for social democrats (Arndt and Rennwald Reference Arndt and Rennwald2016; Flavin and Radcliff Reference Flavin and Radcliff2011; Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021).

Are the four explanations supported by empirical evidence?

The four explanations are summarized in Table 1. They will now be assessed based on empirical research. For each explanatory approach, two hypotheses have been formulated which are presented in the bottom row of the table. For instance, Hypothesis 1 states that the electoral crisis of social democracy is the result of a shrinking working class, while increasing electoral trade-offs are the cause of the electoral decline according to the two variants of Hypothesis 2.

Table 1. Four Explanations for the Electoral Crisis of Social Democracy

The analysis is based on a systematic review of empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journal articles from January 2010 to October 2021. The selection process was oriented at the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. Reference Moher2009) and proceeded in four steps (for a more detailed account see Figure A1 in the Online Appendix):

1. Extensive literature search via Web of Science: 621 studies

2. Screening the identified studies for eligibility: 30 studies

3. Snowball research based on eligible studies: additional 21 studies

4. Categorization of the 51 included studies

A study was assessed as eligible if it offered empirical evidence on at least one of the outlined hypotheses. The resulting 51 studies provide evidence on three different levels. Out of those studies, 14 deal with the determinants of social democrats' vote share (aggregate level) and thus offer the most direct test of the hypotheses. Twenty of the studies provide cross-country evidence on the voter level (i.e. individual level). Those studies generally rely on survey data, which are particularly useful in studying the reasons for turning away from social democrats as well as electoral trade-offs. In addition, 27 studies include analyses on individual social democratic parties, with most studies covering Germany, Britain and the Nordic countries.Footnote 3 The review builds primarily on the cross-country studies due to the high generalizability of the findings, but it also includes strong pieces of evidence provided by country studies (for an overview of the included studies see Tables A1 and A2 in the Online Appendix).

Sociological explanation

According to Hypothesis 1, social democrats' electoral losses result from the shrinking of the working class. Basic evidence comes from Giacomo Benedetto et al. (Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020), who combine an analysis of the determinants of declining vote shares with a look at individual-level support for social democrats. The authors offer qualified support for H1 by concluding that ‘most of the fall in support for social democratic parties in recent years is correlated with a decline in the number of industrial workers as well as a reduction in the propensity of these parties’ core supporters … to vote for them' (Benedetto et al. Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020: 928).Footnote 4 This is supported by Robin Best (Reference Best2011), who shows that group-size effects have strongly contributed to the decline of social democrats' vote share among workers, but that reduced loyalty of workers also plays a role. On the country level, several studies on class voting also stress the latter point by highlighting social democrats' role in the demobilization of the working class (for Germany see Elff and Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2011, Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2017; for the UK see Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2012a, Reference Evans and Tilley2012b; Heath Reference Heath2015, Reference Heath2018). Even with this qualification, the empirical evidence clearly indicates that the shrinking of the working class over time accounts for a part of social democrats' vote losses.

The second hypothesis highlights the role of electoral trade-offs concerning occupational groups (H2a) or labour market insiders and outsiders (H2b) in social democracy's decline. Here, evidence comes exclusively from individual-level studies on voter attitudes and behaviour. Support for the trade-offs between working-class and middle-class voters (H2a) is provided by Line Rennwald and Jonas Pontusson (Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021), though the authors find that this trade-off is mitigated by high unionization. In contrast, Tarik Abou-Chadi and Markus Wagner (Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019) find that strong unions exacerbate the trade-off between manual workers and professionals. There are more conflicting results. Focusing on sociocultural issues, Abou-Chadi and Wagner (Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020) find no trade-off between workers and professionals. Studies focusing on social democrats' positions on immigration indicate the opposite. While Jane Gingrich (Reference Gingrich2017) shows that the potential left coalition of working-class and new middle-class voters is divided on immigration, country studies on Germany (Chou et al. Reference Chou2021) and Denmark (Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2020) point to related electoral trade-off between those groups. On the one hand, the conflicting findings indicate the substantial impact of the methodical approach on the results. On the other hand, the electoral trade-off seems to be conditional on country-specific factors, such as union strength (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019; Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021) and the electoral system (Arndt Reference Arndt2014b).

Concerning the insider–outsider dilemma (H2b), the literature yields similar results. The extent of differences in distributional and political preferences between labour market insiders and outsiders depends on the operationalization of the cleavage, with labour market status being a stronger indicator than labour market risks (Marx Reference Marx2014; Rovny and Rovny Reference Rovny and Rovny2017). The only study that directly tests H2b comes from Johannes Lindvall and David Rueda (Reference Lindvall and Rueda2014). Based on five elections between 1994 and 2010, the authors demonstrate that the Swedish Social Democrats were indeed confronted with the insider–outsider dilemma. Further research is needed to test if H2b holds for other countries.

Materialist explanation

Hypothesis 3 highlights external material constraints, such as globalization (H3a) and fiscal and monetary restrictions in the EU (H3b). Concerning the impact of globalization, the empirical evidence is ambivalent. Based on the KOF globalization index, Benedetto et al. (Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020) find no general negative impact of globalization on the social democratic vote share. In contrast, a recent study by Helen Milner (Reference Milner2021: 2288) which focuses on, among other things, import shocks on the regional level concludes that ‘globalization, especially trade, is associated with declines for mainstream left parties’ and that ‘these effects accelerated with the financial crisis’. The comparison of both studies highlights the impact of the selected globalization indicator. In other words, import shocks on the meso level seem to be a better indicator than globalization indices to capture the negative electoral effects of globalization on social democrats. Turning to the EU and the eurozone (H3b), there is mounting evidence that existing restrictions are indeed detrimental to social democrats. Focusing on election results before and during the euro crisis, Sonia Alonso and Rubén Ruiz-Rufino (Reference Alonso and Ruiz-Rufino2020) show not only that social democrats paid an electoral price for implementing austerity measures but also that this price was considerably higher in countries facing external intervention by the so-called Troika. This finding is corroborated by Sara Hobolt and James Tilley (Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016), who also point to the impact of the euro crisis and fiscal constraints on voters' defection to challenger parties. Finally, Stuart Turnbull-Dugarte (Reference Turnbull-Dugarte2020) shows that left-leaning voters are more likely to abstain from voting than other voters when countries are exposed to EU intervention. In sum, H3b is corroborated for Southern European debtor countries.

Hypothesis 4 highlights the negative impact of austerity measures and other ‘structural reforms’ on social democrats. In addition to the studies by Hobolt and Tilley (Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016) and Alonso and Ruiz-Rufino (Reference Alonso and Ruiz-Rufino2020), Gijs Schumacher et al. (Reference Schumacher, Vis and van Kersbergen2013) and Alexander Horn (Reference Horn2021) confirm the hypothesis that social democrats are punished for welfare retrenchment. According to Horn (Reference Horn2021), the negative effects are permanent and materialize in the long run, irrespective of positive economic effects. In contrast, Nathalie Giger and Moira Nelson (Reference Giger and Nelson2011) as well as Abel Bojar (Reference Bojar2018) find no electoral punishment. This is, however, clearly at odds with findings from country studies. In a comparative study on Germany, UK, Denmark and Sweden, Christoph Arndt (Reference Arndt2013) demonstrates that social democratic parties in all countries suffered electoral setbacks as a consequence of welfare state reforms, with the scale of those setbacks contingent on the electoral system. For Germany, Hanna Schwander and Philip Manow (Reference Schwander and Manow2017) show that the negative long-term effects of the ‘Agenda 2010’ for the SPD resulted mainly from the establishment of a strong competitor on the left. More generally, there is substantial evidence that social democrats tend to benefit from high levels of social spending and, more specifically, spending on labour market policies (Benedetto et al. Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020; Fossati and Trein Reference Fossati and Trein2021; Kweon Reference Kweon2018). Karl Loxbo et al. (Reference Loxbo2021) find, however, a curvilinear relationship, with diminishing social democratic vote shares at higher levels of welfare generosity. On balance, the empirical evidence supports H4, especially in terms of the negative effects of spending cuts.

Ideational explanation

Hypothesis 5 highlights social democrats' neoliberal turn, that is, their rightward shift on the socioeconomic dimension. Here, studies which find no such effect can be contrasted with research that offers general or at least qualified support for this hypothesis. Focusing on the adoption of the ‘third way’ and a rightward shift on the state–market dimension, neither Hans Keman (Reference Keman2011) nor Abou-Chadi and Wagner (Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019, Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020) find support for H5. This stands in stark contrast to the findings by Johannes Karreth et al. (Reference Karreth, Polk and Allen2013) on the long-term effects of moving to the right. Based on survey data from Germany, Britain and Sweden, the latter study shows that ‘the gains [social democratic] parties derived from the policy shift toward the middle in the 1990s were short-lived and came at the expense of electoral success in subsequent decade’ (Karreth et al. Reference Karreth, Polk and Allen2013: 792). This negative long-term effect is in line with Schwander and Manow (Reference Schwander and Manow2017), who demonstrate that the negative electoral effects of the German SPD's neoliberal turn took some time to unfold. Other studies indicate that the effect is contingent on additional factors, such as a proportional electoral system (Arndt Reference Arndt2014b), as this facilitates the voter defection witnessed in the German case, high income inequality (Polacko Reference Polacko2022) and low to moderate levels of welfare generosity (Loxbo et al. Reference Loxbo2021). In sum, the evidence indicates that the negative electoral effect of moving to the right unfolds over time and that its strength is contingent on the political and economic context.

According to Hypothesis 6, it is the adoption of a more libertarian position on the sociocultural dimension that leads to vote losses. The strongest rejection of this hypothesis comes from Abou-Chadi and Wagner (Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020). Based on their analysis of survey data from 13 West European countries, they conclude that ‘more progressive and more pro-EU positions are if anything electorally beneficial to Social Democratic parties’ (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020: 247–248). Inconsistent with H6, workers are not found to be less likely to vote for culturally progressive social democrats. In combination with an investment-oriented economic stance, culturally liberal positions are even found to be beneficial to social democrats if unions are weak (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019). Focusing on the issue of immigration, Jae-Jae Spoon and Heike Klüver (Reference Spoon and Klüver2020) instead come to the conclusion that centre-left parties can profit from ‘going tough on immigration’. Results from country studies on this issue are mixed but mainly not in line with H6. Survey data from Britain indicate that a liberal stance on immigration indeed leads to the defection of voters from Labour (Evans and Mellon Reference Evans and Mellon2016). In contrast, Carl Dahlström and Anders Sundell (Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012) find no support for H6 for elections in Swedish municipalities. For Germany, the empirical evidence shows that a restrictive stance on immigration is either not sufficient to attract radical right voters (Spoon and Klüver Reference Spoon and Klüver2020) or comes at the cost of alienating its own voters (Chou et al. Reference Chou2021).Footnote 5 This corresponds to the findings of a recent survey experiment among Danish voters which shows that Danish Social Democrats face a trade-off between anti-immigration and pro-immigration voters, though a tougher stance on immigration might be beneficial from an office-seeking perspective (Hjorth and Larsen Reference Hjorth and Larsen2020).

Institutional explanation

Hypothesis 7 is derived from cartel party theory and highlights political collaboration and policy convergence with mainstream parties on the right. The empirical evidence mainly supports this hypothesis. On the aggregate level, Benedetto et al. (Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020) find a significant negative effect for social democrats participating as junior partner in coalition governments. On the individual level, further empirical support comes from studies focusing on policy convergence among mainstream parties. Spoon and Klüver (Reference Spoon and Klüver2019) find that those parties' convergence on the left–right scale leads to vote losses as their voters switch to non-mainstream parties. This is in line with Zack Grant's (Reference Grant2021) finding that de-polarization between establishment parties fuels the support of anti-system parties in times of economic crisis (see also Hobolt and Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016). In Sweden, policy convergence between social democrats and centre-right parties on welfare issues has benefited the latter (Arndt Reference Arndt2014a), while convergence on the general left–right dimension and migration have been beneficial to the radical right (Oskarson and Demker Reference Oskarson and Demker2015). In sum, the literature indicates that policy convergence with the centre-right has indeed negative electoral consequences for social democrats.Footnote 6

Hypothesis 8 highlights the negative impact of union decline on social democrats. On the voter level, the literature paints a unanimous picture, since all studies controlling for individual union membership find that union members are more likely to vote for social democrats than non-union members (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019, Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020; Arndt and Rennwald Reference Arndt and Rennwald2016; Kweon Reference Kweon2018; Marx Reference Marx2014; Milner Reference Milner2021; Mosimann et al. Reference Mosimann, Rennwald and Zimmermann2019; Polacko Reference Polacko2022; Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021). Somewhat surprisingly, the effect is quite similar among working-class and middle-class voters (Mosimann et al. Reference Mosimann, Rennwald and Zimmermann2019: 78–80). But does this effect translate to the aggregate level in times of union decline? Here, the results are at first sight rather inconsistent. While Abou-Chadi and Wagner (Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019), Loxbo et al. (Reference Loxbo2021) and Matthew Polacko (Reference Polacko2022) find no significant effect of unionization on the social democratic vote share, Rennwald and Pontusson (Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021: 40) estimate that ‘a one-percentage-point decline in union density is associated with a vote-share decline of nearly half a percentage point’ and demonstrate that strong unions mitigate the trade-off between working-class and middle-class voters. A fine-grained analysis by Arndt and Rennwald (Reference Arndt and Rennwald2016) reveals that the union effect is highly contingent on union confederations, with strong blue-collar and public sector confederations but not white-collar confederations in the private sector having a positive impact on social democrats' vote share. The literature thus lends a qualified support to H8.

Summary

As Table 2 demonstrates, there is not one explanation that stands out. Rather, several factors seem to have contributed to the electoral crisis of social democracy, especially the shrinking of the working class (H1a), austerity measures implemented by social democrats (H4), their neoliberal turn (H5) and their policy convergence with centre-right parties (H7). The first factor reflects long-term socio-structural changes, whereas the three latter factors are parts of a different story which can be summarized as the ideational and institutional neoliberalization of social democracy (Bandau Reference Bandau2021). I will return to this point in the conclusion. H6 receives the least support by the literature, since movements in either direction on the sociocultural dimension risk alienating voters.

Table 2. Findings of the Systematic Review

Note: SD = Social Democrats.

The support for the other hypotheses is more qualified. One important qualification is that negative electoral effects are conditional on other factors. For instance, the supposed electoral trade-offs between different groups of voters are contingent on the electoral system and unions (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2019; Arndt Reference Arndt2014b; Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021). In addition, the literature shows that the interaction of certain factors, such as austerity and EU intervention or policy convergence with the mainstream right in times of economic crises, are highly detrimental to social democrats. These findings indicate that the causes for social democrats' electoral losses are complex and thus might differ among Western European countries. This point is supported by the different images of social democratic decline presented in Figure 1.

Finally, inconsistent evidence for some of the hypotheses is at least in part the product of divergent operationalizations and statistical techniques. The impact of operationalization is best illustrated by the diverging results on electoral behaviour for different operationalizations of labour market outsiders (Rovny and Rovny Reference Rovny and Rovny2017). Concerning statistical techniques, models on the levels of social democratic support can yield different results than first-differences models focusing on short-term vote changes. By applying both kinds of models, Benedetto et al. (Reference Benedetto, Hix and Mastrorocco2020) find that the shrinkage of the working class affects the levels of the social democratic vote share but not the short-term changes between elections (see Table A1 in the Online Appendix). Covering levels and changes thus provides a way to distinguish between long-term and short-term effects.

Conclusion: avenues for future research and the future of social democracy

Based on the findings, there are three starting points for future research: the inconsistency of some of the findings, the relation of individual factors in explaining the electoral crisis of social democracy and the portability of the findings to crisis-ridden left parties in Eastern Europe. Concerning the first point, conflicting results are, as shown, often the product of the used indicators. Here, researchers have not only to look for the best indicators available but also be careful with the interpretation of their findings. For example, recent evidence shows that the sociocultural divide is much stronger for issues such as immigration than for other sociocultural issues (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2022). Such findings have to be taken into account when analysing the electoral consequences of social democrats' programmatic shifts.

Regarding the interplay of various factors, I propose two main avenues for future research. First, researchers should distinguish long-term and short-term causes of social democrats' electoral crisis. As outlined above, estimating models for social democratic vote shares as well as electoral changes between elections offers one promising strategy. A more sophisticated approach is to heed Paul Pierson's (Reference Pierson2004: 102) advice: ‘The connection between “triggers” and “deeper”, more long-term causes suggests that seemingly rival explanations may often be complementary.’ In the case of social democracy, this means combining long-term processes, such as socio-structural changes, with ‘triggers’, such as policy decisions by social democrats in office. Second, the finding that some of the hypotheses only hold under certain conditions points to complex causality at the heart of the crisis of social democracy. Qualitive comparative analysis (QCA) presents an appropriate method to deal with complex causality and related equifinality (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). QCA can thus be applied to determine which constellations of sociological, material, ideational and institutional factors cause social democratic decline. Previous applications of QCA on electoral performance, which have focused on populist and anti-establishment parties (Fernández-García and Luengo Reference Fernández-García and Luengo2019; van Kessel Reference van Kessel2015), provide blueprints for this kind of research.

Finally, this review has centred on the crisis of social democratic parties in Western Europe. However, left parties in Central and Eastern Europe have also suffered substantial electoral defeats in recent years. Though those parties have a special history, some of them being the successors of communist parties, their electoral calamities may have similar causes (Berman and Snegovaya Reference Berman and Snegovaya2019). Indeed, recent studies demonstrate that neoliberal stances and policies have strongly contributed to the left's electoral crisis in Eastern Europe (Bagashka et al. Reference Bagashka, Bodea and Han2022; Snegovaya Reference Snegovaya2022). While this is in line with the findings on Western Europe, further research is needed to get a better understanding of similarities and differences between Eastern and Western European parties.

This leads to the final question: what does all of this mean for the future of social democracy? In general, the review holds a positive and a negative message for social democrats. The negative message is that the shrinkage of the traditional working class reduces social democracy's core electorate, while post-industrial electoral trade-offs change partisan competition and complicate the creation of new electoral coalitions. A return to previous electoral heights is thus all but impossible. The positive message is that the electoral crisis is to some extent the result of the neoliberalization of social democracy. Social democrats' recent adoption of more leftist economic positions and the slightly growing policy divergence between them and centre-right parties thus offer some signs of hope for social democracy (Manwaring and Holloway Reference Manwaring and Holloway2022). However, to permanently halt the downward trend, social democrats have to present a clear alternative to today's ailing neoliberalism.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.10.