Abstract

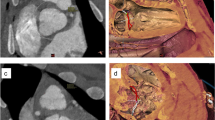

Cardiovascular diseases are a major health concern and therefore an important topic in biomedical research. Large animal models allow researchers to assess the safety and efficacy of new cardiovascular procedures in systems that resemble human anatomy; additionally, they can be used to emulate scenarios for training purposes. Among the many biomedical models that are described in published literature, it is important that researchers understand and select those that are best suited to achieve the aims of their research, that facilitate the humane care and management of their research animals and that best promote the high ethical standards required of animal research. In this resource the authors describe some common swine models that can be easily incorporated into regular practices of research and training at biomedical institutions. These models use both native and altered vascular anatomy of swine to carry out research protocols, such as testing biological reactions to implanted materials, surgically creating aneurysms using autologous tissue and inducing myocardial infarction through closed-chest procedures. Such models can also be used for training, where native and altered vascular anatomy allow medical professionals to learn and practice challenging techniques in anatomy that closely simulates human systems.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Thygesen, K., Alpert, J.S. & White, H.D. on behalf of the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Redefinition of Myocardial Infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50, 2173–2195 (2007).

Roger, V.L. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update. Circulation 123, e18–e209 (2011).

Monnet, E. & Chachques, J.C. Animal models of heart failure: what is new? Ann. Thorac. Surg. 79, 1445–1453 (2005).

Sakaguchi, G. et al. A pig model of chronic heart failure by intracoronary embolization with gelatin sponge. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 75, 1942–1947 (2003).

Suzuki, Y., Yeung, A.C. & Ikeno, F. The pre-clinical animal model in the translational research of interventional cardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Intv. 2, 373–383 (2009).

Ruiz-Meana, M., Martinson, E.A., Garcia-Dorado, D. & Piper, H.M. Animal ethics in cardiovascular research. Cardiovasc. Res. 93, 1–3 (2012).

Hooijmans, C., de Vries, R., Leenaars, M. & Ritskes-Hoitinga, M. The Gold Standard Publication Checklist (GSPC) for improved design, reporting and scientific quality of animal studies GSPC versus ARRIVE guidelines. Lab. Anim. 45, 61 (2011).

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W.J., Cuthill, I.C., Emerson, M. & Altman, D.G. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000412 (2010).

Dixon, J.A. & Spinale, F.G. Large animal models of heart failure: a critical link in the translation of basic science to clinical practice. Circ. Heart Fail. 2, 262–271 (2009).

Suzuki, Y., Yeung, A.C. & Ikeno, F. The representative porcine model for human cardiovascular disease. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 195483 (2011).

Suzuki, Y., Lyons, J.K., Yeung, A.C. & Ikeno, F. In vivo porcine model of reperfused myocardial infarction: In situ double staining to measure precise infarct area/area at risk. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 71, 100–107 (2008).

Kuster, D. et al. Left ventricular remodeling in swine after myocardial infarction: a transcriptional genomics approach. Basic Res. Cardiol. 106, 1269–1281 (2011).

Kraitchman, D.L. et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction. Circulation 107, 2290–2293 (2003).

Kelley, K.W., Curtis, S.E., Marzan, G.T., Karara, H.M. & Anderson, C.R. Body surface area of female swine. J. Anim. Sci. 36, 927–930 (1973).

Swindle, M.M., Makin, A., Herron, A.J., Clubb, F.J. & Frazier, K.S. Swine as models in biomedical research and toxicology testing. Vet. Pathol. 49, 344–356 (2012).

Fernández-Portales, J., Sun, F., Crisóstomo, V., Báez, C. & Pérez de Prado, A. Modelos animales en el aprendizaje de cardiología intervencionista. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 13, 40–46 (2013).

Dondelinger, R.F. et al. Relevant radiological anatomy of the pig as a training model in interventional radiology. Eur. Radiol. 8, 1254–1273 (1998).

Zaragoza, C. et al. Animal models of cardiovascular diseases. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 497841 (2011).

Braun, A. et al. Effects of an alpha-4 integrin inhibitor on restenosis in a new porcine model combining endothelial denudation and stent placement. PLoS One 5, e14314 (2010).

Won, H. et al. Serial changes of neointimal tissue after everolimus-eluting stent implantation in porcine coronary artery: an optical coherence tomography analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 851676 (2014).

Tahara, S., Chamié, D., Baibars, M., Alraies, C. & Costa, M. Optical coherence tomography endpoints in stent clinical investigations: strut coverage. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 27, 271–287 (2011).

Schwartz, R.S. et al. Drug-eluting stents in preclinical studies: updated consensus recommendations for preclinical evaluation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 1, 143–153 (2008).

Schwartz, R.S. et al. Preclinical evaluation of drug-eluting stents for peripheral applications: recommendations from an expert consensus group. Circulation 110, 2498–2505 (2004).

Massoud, T.F., Guglielmi, G., Ji, C., Viñuela, F. & Duckwiler, G.R. Experimental saccular aneurysms. I. Review of surgically-constructed models and their laboratory applications. Neuroradiology 36, 537–546 (1994).

Maynar, M. et al. An animal model of abdominal aortic aneurysm created with peritoneal patch: technique and initial results. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 26, 168–176 (2003).

Guglielmi, G. et al. Experimental saccular aneurysms. II. A new model in swine. Neuroradiology 36, 547–550 (1994).

Murayama, Y. et al. Development of the biologically active Guglielmi detachable coil for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Part II: an experimental study in a swine aneurysm model. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 20, 1992–1999 (1999).

Murayama, Y., Viñuela, F., Tateshima, S., Viñuela, F. Jr. & Akiba, Y. Endovascular treatment of experimental aneurysms by use of a combination of liquid embolic agents and protective devices. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 21, 1726–1735 (2000).

Takao, H. et al. Endovascular treatment of experimental aneyrysms using a combination of thermoreversible gelation polymer and protection devices: feasibility study. Neurosurgery 65, 601–609 (2009).

Ding, P. et al. Horner syndrome after carotid sheath surgery in a pig: anatomic study of cervical sympathetic chain. Comp. Med. 61, 453–456 (2011).

Hughes, G.C., Post, M.J., Simons, M. & Annex, B.H. Translational physiology: porcine models of human coronary artery disease: implications for preclinical trials of therapeutic angiogenesis. J. Appl Physiol. 94, 1689–1701 (2003).

Arenal, A. et al. Noninvasive identification of epicardial ventricular tachycardia substrate by magnetic resonance-based signal intensity mapping. Heart Rhythm 11, 1456–1464 (2014).

Hughes, H.C. Swine in cardiovascular research. Lab. Anim. Sci. 36, 348–350 (1986).

Kraitchman, D.L., Bluemke, D.A., Chin, B.B. & Heldman, A.W. A minimally invasive method for creating coronary stenosis in a swine model for MRI and SPECT imaging. Invest. Radiol. 35, 445–451 (2000).

Gálvez-Montón, C. et al. Comparison of two preclinical myocardial infarct models: coronary coil deployment versus surgical ligation. J. Transl. Med. 12, 137 (2014).

Crisóstomo, V. et al. Development of a closed chest model of chronic myocardial infarction in swine: magnetic resonance imaging and pathological evaluation. ISRN Cardiol. 2013, 781762 (2013).

Gálvez-Montón, C. et al. Post-infarction scar coverage using a pericardial-derived vascular adipose flap. Pre-clinical results. Int. J. Cardiol. 166, 469–474 (2013).

Eldar, M. et al. Percutaneous multielectrode endocardial mapping during ventricular tachycardia in the swine model. Circulation 94, 1125–1130 (1996).

Klein, H.H., Schubothe, M., Nebendahl, K. & Kreuzer, H. Temporal and spatial development of infarcts in porcine hearts. Basic Res. Cardiol. 79, 440–447 (1984).

Pérez de Prado, A. et al. Closed-chest experimental porcine model of acute myocardial infarction-reperfusion. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 60, 301–306 (2009).

Schuleri, K.H. et al. The adult Gottingen minipig as a model for chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction: focus on cardiovascular imaging and regenerative therapies. Comp. Med. 58, 568–579 (2008).

Sasano, T., Kelemen, K., Greener, I.D. & Donahue, J.K. Ventricular tachycardia from the healed myocardial infarction scar: validation of an animal model and utility of gene therapy. Heart Rhythm 6, S91–S97 (2009).

McCall, F.C. et al. Myocardial infarction and intramyocardial injection models in swine. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1479–1496 (2012).

Crisóstomo, V. et al. Delayed administration of allogeneic cardiac stem cell therapy for acute myocardial infarction could ameliorate adverse remodeling: experimental study in swine. J. Transl. Med. 13, 156 (2015).

Fu, Y. et al. Fused X-ray and MR imaging guidance of intrapericardial delivery of microencapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells in immunocompetent swine. Radiology 272, 427–437 (2014).

Malliaras, K. et al. Validation of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to monitor regenerative efficacy after cell therapy in a porcine model of convalescent myocardial infarction. Circulation 128, 2764–2775 (2013).

Johnston, P.V. et al. Engraftment, differentiation, and functional benefits of autologous cardiosphere-derived cells in porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 120, 1075–1083 (2009).

Usón-Gargallo, J., Pérez-Merino, E.M. & Usón-Casaús, J.M. Sánchez-Fernández, J. & Sánchez-Margallo, F.M. Modelo de formación piramidal para la enseñanza de cirugía laparoscópica. Cir. Cir. 81, 420–430 (2013).

Bouzeghrane, F., Naggara, O., Kallmes, D.F., Berenstein, A. & Raymond, J. In vivo experimental intracranial aneurysm models: a systematic review. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 31, 418–423 (2010).

Namba, K., Mashio, K., Kawamura, Y., Higaki, A. & Nemoto, S. Swine hybrid aneurysm model for endovascular surgery training. Interv. Neuroradiol. 19, 153–158 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Juan Maestre, María Borrega, Alejandra Usón and Helena Martín for their outstanding technical assistance during experimental work. We also thank Carmen Calles-Vazquez, PhD and Javier Fernandez-Portales, PhD, for their excellent technical help during the creation of various models.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crisóstomo, V., Sun, F., Maynar, M. et al. Common swine models of cardiovascular disease for research and training. Lab Anim 45, 67–74 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/laban.935

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/laban.935

This article is cited by

Free-breathing gradient recalled echo-based CMR in a swine heart failure model

Scientific Reports (2022)

Selective Enhancement of Swine Myocardium with a Novel Ultrasound Enhancing Agent During Transthoracic Echocardiography

Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research (2022)

Radiological Arterial Anatomy in Mature Microminipigs as a Pre-clinical Research Model in Interventional Radiology

CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology (2022)

Adipose-Derived Stromal/Stem Cells from Large Animal Models: from Basic to Applied Science

Stem Cell Reviews and Reports (2021)

Epigenetic clock and DNA methylation analysis of porcine models of aging and obesity

GeroScience (2021)