“It takes a village to raise a child,” university teachers’ views on traditional education, modern education, and future I integration in Ethiopia

- 1College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 2Faculty of Medicine, University Health Network and Temerty, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Introduction: Indigenous education has recently gained prominence in international debates for its role in addressing the social, economic, and political issues faced by African states. Ethiopia, like other African countries, had its education system based primarily on the transmission of socio-professional aptitudes, religious values, skills, and intergenerational knowledge as a way to preserve the social, cultural, and religious values of the Ethiopian community. In the early 20th century, Ethiopia wholeheartedly adopted a Western higher education system in a tabula rasa approach that sought to obliterate deeply rooted cultural norms and rapidly transition the country’s traditional religious system to a secular one.

Methods: This qualitative study used semi-structured interviews to explore the perspectives of Ethiopian university teachers about the benefits and limitations of traditional education and the potential to integrate traditional and modern education in Ethiopian universities.

Results: Study findings show that, despite agreement that “traditional” education is distinct from other educational systems, there are varying notions of what constitutes “indigenous” education. Participants also suggested that the dominant rationale for the tabula rasa approach in Ethiopian modern education was to modernise the country and embrace a global perspective on education that incorporates ideas and advances from other cultures while still being firmly entrenched in local values and educational systems.

Discussion: Insights have implications for education systems in African and other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in terms of developing strategies for the pluralistic approach to knowledge systems.

Introduction

Education can be a crucial tool for tackling inequality and poverty in global society. It is also a way of transmitting human values, aptitudes, concepts, and knowledge and is, therefore, a vital part of a society’s ability to reproduce itself (Milkias, 1976). According to Grigorenko (2007), Western (or modern) education is a dominant, secular system with a predetermined schedule that uses a curriculum, textbooks, and an alphabet. Modern education originated in Europe and spread across the world after the 15th century, leading to the modernization of social life through science and technological advancement (Alatas, 2006). The word “modern” here refers only to the period when the Western model of formal education emerged and does not denote the relevance or quality of that education.

European missionaries introduced an educational system intended to advance the adoption of Christianity in Africa (Fafunwa, 2018). This education, whether provided by missionaries or colonial officials, encouraged Africans to give up their traditional customs, which benefited colonial interests. The 20th-century educational scholarship acknowledged that there are fundamental life values that are mostly passed down via education from one generation to the next (Tyler, 1949). Tyler notes that educational philosophers believe that the primary goal of education is to transmit the fundamental values learned through in-depth philosophical study. While the positive values of Western cultures may be transferred through formal education, fundamental values are deep and extremely cultural and, as a result, not easily transferrable (Asgedom, 2005). As is often the case, attempts to fully apply Western models of education in non-Western societies have often been met with resistance and challenges due to the deep cultural values and differences between the two.

Ethiopia had an educational system that was built largely on the transfer of socio-professional aptitudes, religious values, skills, and intergenerational knowledge as a way to uphold the social, cultural, and religious values of the society (Pankhurst, 1972). In Ethiopia, so-called modern education was started in approximately 1908 (Dreijmanis and Wagaw, 1996). Ethiopians are proud that their nation was never colonised and that Christianity was introduced there in the first century, centuries before it happened in Europe. With the establishment of a colonial-style educational system, this cultural freedom changed. Postcolonial theorists postulate that Ethiopia has been a victim of Western educational systems due to poor planning by its political leaders, North American, and European imperialism, as well as the actions of international development and financial organizations (Carnoy, 1977; Spring, 1998). Japan, for comparison, introduced modern education very differently. Through the use of foreign teachers and textbooks as well as by sending Japanese students to Western nations for higher education, Japan has heavily borrowed from the West (Tokiomi, 1968). However, the Japanese ruling elite recognized that without a firm foundation in Japan’s traditional heritage, an education system modeled on the West would be uprooted, and so they ensured that traditional values were incorporated (Keenleyside and Thomas, 1937). In many African countries, local cultural traditions are not maintained in higher education settings (Dei, 2004). In Ethiopia, a 17-century-old indigenous education system was ignored when Western forms of modern education were introduced.

Ethiopian and Kenyan experiences show that the Western educational system predominates and does not draw on the indigenous knowledge bases of these countries. Because of this, students in Ethiopia, the environment, and the country’s growth are not significantly influenced by Western education that is not contextualised (Asgedom, 2005; Owuor, 2007). Furthermore, it has been suggested that Western education in Africa as a whole has little impact on social goals (Kaya and Seleti, 2013; Heleta, 2016) or development initiatives (Mawere, 2015).

Some African and Native American educators have argued for the incorporation of cultural values or local ways of knowing in science teaching (Gregory, 1994; Tedla, 1995). In an attempt to promote education for sustainable development and address some of the problems that now afflict African cultures and communities, there is growing interest in comprehending the dynamics of local settings (Owuor, 2007). These dynamics also involve how indigenous practices and knowledge are incorporated into development processes, according to Dei (2002), Angioni (2003), and UNESCO (2006). This is summed up in UNESCO (2006) document, which states than an indigenous approach to education “is an attempt to promote education for sustainable development of African societies where cultures and ways of life are balanced with global and international pressures and demands.”

Ethiopian education has shifted away from preserving historical and traditional values since the advent of modern education. In this approach, all the previous curricula place a heavy focus on the Western-dominated knowledge system (Sisay, 2017). Teferra et al. (2018) assessed the current and previous curricula as being overly laden with academic disciplines and materials. To overcome societal problems, the country today needs citizens with a creative understanding of the knowledge system connected to both indigenous and Western best educational practices (Federal Democratic Republic Government of Ethiopia, 1994; Federal Ministry of Education, 2021).

In Ethiopia, little is currently known about the perspectives of university teachers on the topics of traditional education, modern education, and the potential and ways of integrating the two. The purpose of this study was to examine the perceptions of university teachers about modern education, traditional education, and possible ways of integrating the two in Ethiopia. The following research questions guided the study:

a. What are university teachers’ perspectives on the role of Ethiopian traditional education in the educational development of Ethiopia?

b. How do university teachers describe modern Ethiopian education?

c. What might be some possible ways of integrating traditional education with modern education?

Traditional (Indigenous) education

Traditional (Indigenous) Education is a holistic and community-based approach to education rooted in the cultural knowledge, values, and practices of indigenous peoples (Battiste, 2013). It encompasses the knowledge, values, skills, and socialization processes that have historically been used to educate individuals within African communities (UNESCO, 2003). Traditional education in Africa is deeply rooted in the cultural, social, and spiritual fabric of African societies and plays a crucial role in the transmission of cultural heritage, identity, and community values (Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA), 2006). It is critical to acknowledge the diversity and variances seen in traditional education throughout African ethnic groups, geographical areas, and historical circumstances. Although traditional education has certain basic concepts and practices, there can be notable differences in content, approaches, and priorities (Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA), 2006). Traditional (Indigenous) education is a community-based approach to education that emphasizes experiential learning, intergenerational transmission of knowledge, and the integration of cultural practices, values, and languages (Smith, 2012).

It emphasizes the interconnectedness of individuals with their families, communities, and the natural environment. This community-oriented approach to education in Africa was deeply intertwined with traditional religious beliefs and practices, as emphasized by Mbiti (1990). African culture does not draw clear boundaries between religious and secular domains, resulting in a seamless integration of indigenous education into the tapestry of daily life. Education, in this context, is viewed holistically, forming an integral part of individuals’ overall existence rather than being seen as a distinct process or institution. Building upon this understanding, this study defines indigenous knowledge as a body of native wisdom deeply rooted in the nation’s rich history, customs, and traditions, specifically tied to a particular geographic area. Notably, in Ethiopia, traditional education systems exhibit strong connections with religious practices, further exemplifying the interconnectedness of indigenous knowledge, cultural heritage, and religious beliefs within the educational framework.

Thus, this research study aligns with the established concept of community-oriented education, the integration of traditional religious beliefs, and the holistic nature of indigenous education prevalent in African contexts.

Modern (Western) education

Modern (Western) education in Africa encompasses the adoption of Western educational practices and methodologies, including a focus on literacy, numeracy, and scientific knowledge. It aims to prepare individuals for employment, social mobility, and participation in the global knowledge economy (Brock-Utne, 2002).

Modern education in an African context encompasses the educational systems and practices influenced by European and Western models, which were introduced during the colonial period and have continued to shape education in many African countries. It involves the adoption of Western curricula, pedagogical methods, and organizational structures. Mamdani (2007) defines Western education in Africa as the education systems introduced by European colonizers during the colonial era. These systems typically involve the adoption of European languages, curricula, and pedagogical methods, which have had a profound impact on the educational systems in many African countries. Modern education often emphasizes disciplines like math, science, language, social sciences, and the humanities in the African environment. The curriculum is meant to get students ready for work, further study, and engagement in the global information economy. It seeks to foster creativity and innovation while strengthening communication, critical thinking, problem-solving, and digital literacy abilities (Team, G and Initiative, N, 2014).

Theoretical framework

The study used postcolonial theory, decoloniality, and the Two-Eyed Seeing methodology to examine the factors impacting the beginning of modern education, traditional education, and the integration of indigenous education in Ethiopia.

Postcolonial theories

Theoretical framing in this study focuses on postcolonialism, arguing that poverty in underdeveloped countries stems from imperialism. The need to critically analyze the colonial legacies that continue to influence educational practices, policies, and curricula in African nations is emphasized by postcolonial theory in education. It draws attention to the ways that indigenous knowledge, languages, and cultural traditions have been subordinated to Western knowledge systems and ideals (Mignolo, 2011). One manifestation of this is through privileging one form of knowledge or power through institutions such as publishing corporations, research organizations, institutes of higher education, and testing services (Weiler, 2001). In addition to criticizing the Eurocentric biases in educational curriculum, postcolonial theory in education advocates for the inclusion of African viewpoints, histories, and literature (Ngugi wa Thiong’o, 1986). By opposing the predominance of Western epistemologies and encouraging the creation of inclusive, culturally relevant pedagogies, it promotes the decolonization of education (Sleeter, 2012). In the case of Ethiopia, imperial efforts affected the country’s academic institutions, trade organizations, and enterprises. In the postcolonial context, education is seen as an investment to produce skilled workers for multinational corporations and encourage migration, rather than as a means of empowering communities (Spring, 1998).

Decoloniality

Coloniality takes the form of the “colonization of imagination” or the “colonization of the mind,” as well as the “colonization of knowledge and power” in the field of knowledge production. Decolonial perspectives aim to challenge the dominant beliefs and values of modernity regarding knowledge production and introduce new approaches to research that acknowledge alternative perspectives (Stein et al., 2020). Mignolo (2011) describes decoloniality as “a way of being in the world” and a way to question the existing constructs of knowledge. A critical analysis of the ways that colonialism created educational systems and maintained power disparities is necessary for decoloniality in education. It highlights the necessity of recentering marginalized and indigenous knowledge while decentering Western knowledge and views (Maldonado-Torres, 2007). By upending the prevalent narratives and epistemologies that colonial powers imposed, this framework aims to advance more inclusive and equitable education for all. Decolonization in education also promotes the growth of pedagogies based on empowerment, social justice, and critical consciousness. It advocates a transformational pedagogy that encourages critical thinking, agency, and social change and opposes the continuation of repressive structures and practices inside educational institutions (Hooks, 1994).

Two-eyed seeing

Two-eyed Seeing has developed from Mi’kmaq traditions and is increasingly incorporated into work with Indigenous peoples in North America. It refers to “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledge and ways of knowing and to use both of these eyes together for the benefit of all” (Bartlett et al., 2012). According to Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall, two-eyed seeing involves weaving between different ways of knowing, recognizing that Indigenous knowledge and Western knowledge can both be valuable depending on the situation (Bartlett et al., 2012).

There have been three recent reviews of the uses, applications, and guiding principles of two-eyed seeing approaches in Indigenous health research, which highlight their potential. Like many theoretical approaches, two-eyed seeing can be used in diverse ways. However, it can be a compelling way to think across different ways of knowing, finding richness by juxtaposing alternate worldviews (Wright et al., 2019; Forbes et al., 2020; Roher et al., 2021).

We therefore chose to draw on it when comparing traditional Ethiopian and Western forms of education.

Traditional education in Ethiopia

There is no agreed-upon definition of indigenous knowledge (Kelman et al., 2012). In this Ethiopian research study, indigenous knowledge is defined as native knowledge rooted in a country’s rich history, customs, and traditions that are exclusive to a given geographic area. In Ethiopia, these traditional education systems have strong religious connections.

The arrival of Orthodox Christianity in the fourth century marked the beginning of Ethiopian Orthodox Church education when preschoolers began to learn basic literacy (Pankhurst, 1972). This was followed by the first Hijrah, or migration, of Muslims to Ethiopia in the 7th century, resulting in the opening of Quranic schools that teach early Arabic reading to Muslim children in the country (Serbessa, 2006). Some scholars argue that traditional education in Ethiopia existed before the arrival of Christianity. Gemechu (2016) suggests that Ethiopian Orthodox education encompassed a broader range of knowledge and skills, including non-religious activities such as farming and handicrafts. These skills and abilities were cultivated and passed down through social interactions. Ephraim (1971) suggests that education in Ethiopia originated from gatherings of educated individuals associated with Ethiopian Jewish synagogues, predating the arrival of Christianity. Although modern education is considered a turning point of relative discontinuity, both the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Quranic schools continue to provide education for a large number of students (Kassaye, 2005).

Study overview

In this study, our primary goal was to examine how Ethiopian university professors perceive modern Ethiopian education, the function of traditional education, and potential future directions of integrated Ethiopian education. Using qualitative research methods, a literature review, and input from the research team, we developed a semi-structured interview that aimed to explore the university teachers’ perspectives.

Methods

Study setting

Addis Ababa University’s College of Health Sciences and School of Medicine in Ethiopia is a prestigious institution renowned for its commitment to excellence in medical education, research, and healthcare delivery. The college attracts a significant number of students each year, offering undergraduate, postgraduate, and doctoral programs in various health-related disciplines. It boasts a highly qualified and diverse faculty who play a crucial role in imparting knowledge, mentoring students, and conducting impactful research. The institution’s infrastructure is equipped with modern facilities, including lecture halls, laboratories, simulation centers, clinical skills training centers, and extensive medical literature in libraries. The School of Medicine provides comprehensive clinical training opportunities in collaboration with renowned hospitals and healthcare institutions, enhancing students’ clinical skills and diagnostic abilities. Research is a key focus, with faculty and students engaging in projects addressing prevalent health challenges such as infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, and maternal and child health. Collaborations with national and international research institutions, governmental organizations, NGOs, and industry partners foster knowledge exchange and collaborative research projects. The institution actively engages with the community through research, community health interventions, and outreach programs, aiming to improve healthcare access, delivery, and outcomes.

Recruitment and participants

Professors at AAU who had each received both traditional and modern education made up the population of this study using purposive sampling. The participant group comprised seven university teachers who are current or former faculty members at AAU. All the participants were men; their ages ranged from 64 to 80 (mean age of 72); and their teaching experience ranged from 30 to 37 years (median of 33.5). The study intentionally selected older participants who had experienced both traditional and modern education in Ethiopia to investigate the transition between the two. Their higher age ensured they had valuable life experience and a historical perspective on educational changes. The age range was chosen to focus on the period when traditional education prevailed, allowing for a retrospective analysis of educational practices. The decision to include only male participants reflects the historical context of limited access to education for women in Ethiopia. While gender representation is important, the study aimed to capture the perspectives of individuals with firsthand knowledge of the historical educational context, considering the constraints imposed by historical circumstances.

Data collection

We conducted seven interviews with five teachers from the School of Medicine and two from the social sciences departments. The interviews were conducted in Amharic, the official language of the country, by the first author of this paper. The author was pursuing a master’s degree in a health professional education program and conducting research for his thesis.

Single-session interviews lasting between 45 and 60 min were conducted at a private location convenient to the participant, tape-recorded, and supplemented with field notes. Making use of the (Malterud et al., 2016) concept of information power, the following five items influenced the determination of the sample size for this study: a relatively narrow study aim; a sample with highly specific experience and knowledge that was sampled purposefully; an existing theory that could be used in the analysis set-up of the work; strong dialogs with participants; and data analyzed as one case.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed from Amharic into English by the first author. The data analysis aimed to learn about the participants’ understanding of modern education, the role of traditional education, and the possible ways of integrating the two. Sensitizing concepts were used to inform initial thematic coding, while broader and new content and concepts were actively captured. Frequent and salient codes were identified, and thematically linked codes were clustered to generate distinct and informative thematic categories.

Findings

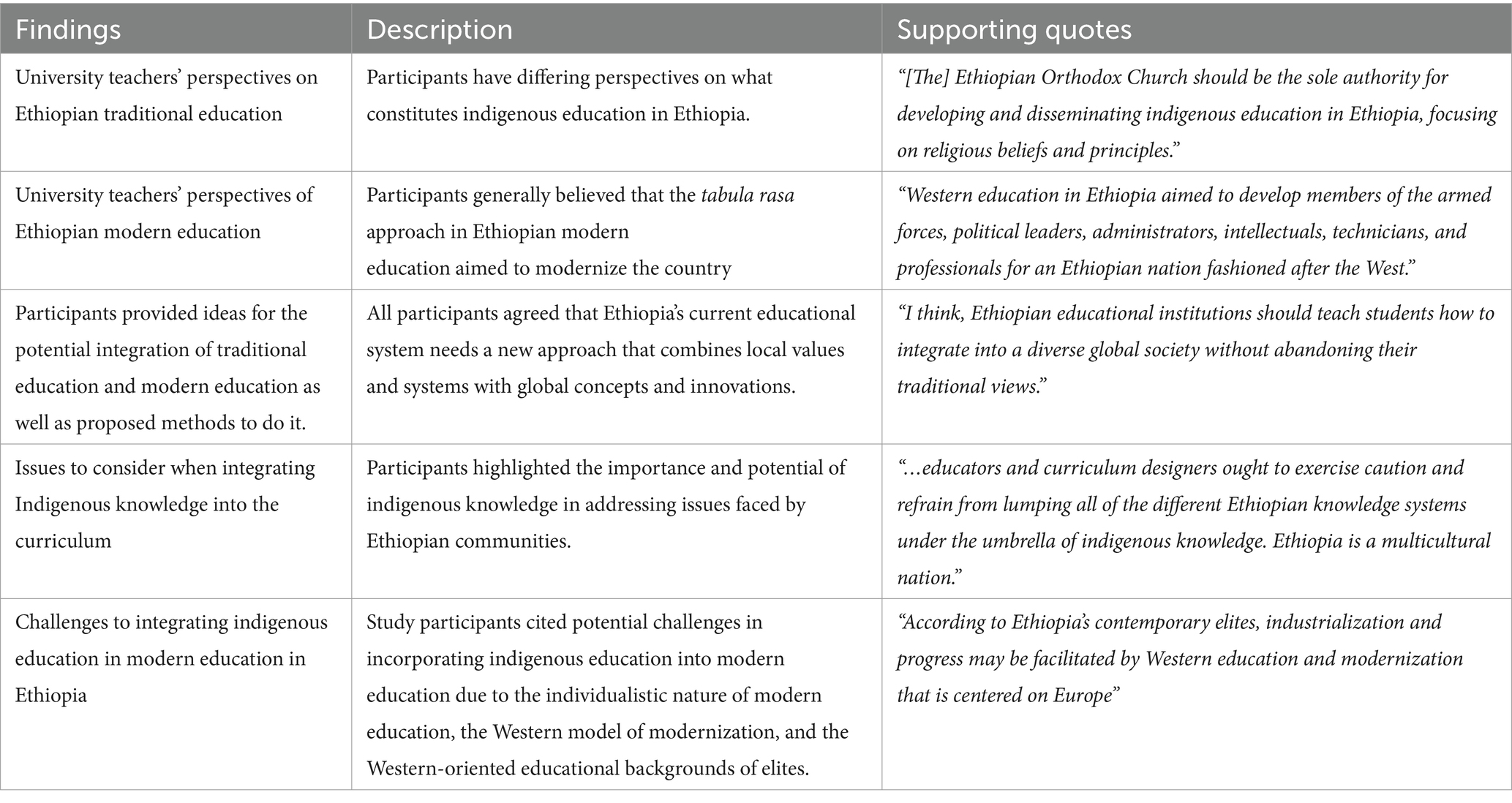

The findings were organized to focus on the perspectives of educators on each of the three research questions, namely: traditional education, modern education, and potential future directions for education in Ethiopia (see Table 1).

University teachers’ perspectives on Ethiopian traditional education

Participants have differing perspectives on what constitutes indigenous education in Ethiopia.

All participants agreed that traditional education belongs in a separate category from other educational systems; however, they disagreed about what constitutes indigenous education. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church and other indigenous learning institutions were mentioned, along with several ancient Ethiopian knowledge-acquisition processes.

One participant (T.1) stated that the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is the only institution with jurisdiction over indigenous education.

“[The] Ethiopian Orthodox Church should be the sole authority for developing and disseminating indigenous education in Ethiopia, focusing on religious beliefs and principles.”

Another participant (T.5) reported that indigenous learning outside of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church is the most ubiquitous and effective kind of education.

“The most pervasive and powerful education is the indigenous learning and teaching that takes place outside the church, which includes studying at home, on farms, and in markets, among other locations where young people may gain skills, knowledge, morals, and virtues.”

Participants described how knowledge can be known and taught in indigenous education. The most frequently mentioned modes were relationality, constructivism, interpretative viewpoint, memorization, and worldview.

According to some research participants, interactions with other students, teachers, families, and community members in general are the primary emphasis of learning opportunities in indigenous education.

According to one participant (T.1):

“Young village children receive education from family, relatives, and the community, gaining knowledge from diverse backgrounds.”

Another participant (T.7) echoed with a proverb:

“This is best summed up by the proverb, ‘It takes a whole village to raise a child.’”

The other respondents (T. 6) claimed that traditional Ethiopian Orthodox Church teaching uses a constructivist theoretical framework:

“Interaction between students, instructors, families, and village elders is encouraged so that they can learn via practical application.”

Another participant (T.3) concurred that:

“The teacher allows pairs of students to teach each other in a class.”

Another participant (T.2) reported that:

“In my traditional school, teachers are drawn from the community at large, and everyone teaches.”

Participants noted how the Ethiopian Orthodox Church’s indigenous education program influenced Ethiopian intellectuals, promoting interpretative viewpoints.

In an Ethiopian Orthodox Church, one participant (T.6) stated:

“I am aware that concepts and texts used in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church schools were drawn from a variety of sources, including non-Christian ones, but were then modified and rebuilt to support domestic national precepts and ideals.”

Another participant (T.7) noted that translations in the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church were contextualised and interpreted based on the cultural context:

“I know that many texts from Greek and Hebraic sources have been translated; these translations were contextual and interpreted according to the local understanding.”

According to research participants, memorization can be vital for fostering creativity and developing lifelong mental skills.

One participant (T.2) reported that memorization helped him learn better:

“Memorization practices strengthen religious instruction by building lifetime mental capacities, boosting attention and memory, and nimble functioning.”

Another participant (T.1) noted that memorization may be a good environment for the growth of creativity.

“I disagree with some who claim that memorization has a careless reputation. What I do know is that it may be a conducive setting for the development of imagination.”

One participant (T.4) voiced his criticism of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church system of memorization:

“The Church school’s flaws, which included a lack of critical thinking and originality, resulted from its reliance on memorization by rote.”

Some participants argued that an indigenous worldview, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of the spiritual, natural, and human realms, forms the basis for Ethiopian indigenous education.

One participant (T. 6) reported that his church education helped him build the moral fiber:

“My church’s educational program helped me develop intellectually and spiritually, and most importantly, it helped me develop the character required to maintain a communal lifestyle.”

Another participant (T.3) stated:

“The indigenous education system in Ethiopia encourages a sense of community and active involvement in family and societal concerns by offering classes in virtue, character, literature, agriculture, and crafts.”

University teachers’ perspectives on Ethiopian modern education

Participants generally believed that the tabula rasa approach in Ethiopian modern education aimed to modernize the country. Most participants agreed that Ethiopian officials prioritize modern education and marginalize traditional schools as the key to overcoming poverty and achieving Western economic and social progress. The following were the most frequent attitudes toward the beginning of modern education:

One participant (T.5) stated:

“In my opinion, given the reality of the modern world, it is very difficult to explain that an education restricted to the teaching of religion and way of life can fulfill the ambitions of the population.”

One participant (T.7) asserted that Ethiopian elites believed Western education may help societies transition:

“Society must progressively evolve from simple to complex, from primitivism to science, and from traditionalism to modernity with the notion of Western education after receiving my Western education overseas.”

Another participant (T.1) reported:

“I think Ethiopian authorities have imitated techniques that have produced money, power, or knowledge in other parts of the world to modernize the state; one of these strategies was education.”

Participants suggested that Western education in Ethiopia aimed to develop leaders and intellectuals using Western models, while Western advisors embraced their ideologies.

One participant (T.3) reported that:

“The aim of Western education in Ethiopia was to develop members of the armed forces, political leaders, administrators, intellectuals, technicians, and professionals for an Ethiopian nation fashioned after the West.”

Another participant (T.2) reported that Western education advisors had a different agenda during the process of importing Western education: they were working hard to import ideology.

“The goal of importing Western education was to advance individualism, secularism, and materialism—liberal principles crucial to the growth of a civilised society.”

Participants acknowledged that the instructional materials and methods in Ethiopian modern education were alien to students.

Most of the participants acknowledged that the teaching strategies and resources used in contemporary Ethiopian education were foreign to pupils.

According to one participant (T.5), almost everything was alien during the beginning of modern education:

“There were only pupils who were native to Ethiopia. The principal, teachers, instructor, blackboard, book, and other foreign objects were imported.”

The educational materials have little to do with pupils, according to one participant (T.2):

“There is no connection between what is discussed and demonstrated in the classroom—utilizing textbooks, brochures, handouts, study guides, and manuals—and the realities of Ethiopian students.”

Participants highlighted the various consequences of Ethiopia’s tabula rasa approach to modern education. They identified the impacts of the sudden shift from traditional to modern schooling, including the loss of national identity, improved living standards, and technology transfer. According to the respondents, the modern educational system undermines national identity and cultural heritage.

One participant (T.4) reported:

“My children and grandchildren, after receiving modern education, exhibit a concerning disregard for their ancestors. They have become disconnected from their Ethiopian identity and culture, adopting foreign customs instead.”

Another participant (T.2) claimed:

“It is obvious that the Western educational system has stifled the cultural worldviews, traditions, and practices of our youngsters. Their worldview and sense of self are only informed by what they already know about the West.”

Another participant (T.6) stated:

“Graduates refuse to assist the impoverished individuals who helped them receive a free education. As a result, many of these people are risking their lives to cross oceans in search of a better life and the American dream.”

Western education, according to some participants, helped Ethiopians enhance their quality of life, access to public services, and ability to acquire wealth, use technology, and enjoy comforts.

One participant (T.2) claimed:

“Because they use technological solutions, current Ethiopians enjoy better living conditions than their forebears.”

Another participant (T.1) reported:

“Access to numerous technical advancements made possible by Western education makes it feasible to improve the quality of life...”

Participants provided ideas for the potential integration of traditional education and modern education, as well as proposed methods to do it

A step in the right direction

All participants agreed that Ethiopia’s current educational system needs a new approach that combines local values and systems with global concepts and innovations. They proposed various methods for integrating indigenous education with the modern system, such as transitioning between different epistemologies, synthesizing global and local education, and incorporating worldviews.

Ethiopia seeks a paradigm shift from the Western model to incorporate global and local education for globalization challenges.

One participant (T.3) stated

“an educational system in the 21st century that is strongly rooted in Ethiopian philosophy and education while carefully absorbing, adapting, and borrowing ideas, concepts, knowledge, technology, and information from the outside world.”

One participant (T.1) stated:

“I think Ethiopian educational institutions should teach students how to integrate into a diverse global society without abandoning their traditional views.”

Issues to consider when integrating Indigenous knowledge into the curriculum

Participants highlighted the importance and potential of indigenous knowledge in addressing issues faced by Ethiopian communities. However, educators must consider the implications and sustainability of incorporating this knowledge into modern education and its impact on pedagogy.

One participant (T.2) suggested it was wise to be cautious and avoid bundling together the diverse Ethiopian ways of knowing:

“educators and curriculum designers ought to exercise caution and refrain from lumping all of the different Ethiopian knowledge systems under the umbrella of indigenous knowledge. Ethiopia is a multicultural nation.”

Another participant (T.4) raised cultural gender issues:

“I believe that indigenous knowledge in Ethiopia is gendered, leading to distinct and often complementary roles and responsibilities for men and women, with significant social implications. The government's efforts to address gender inequalities through inclusive education may be undermined if educators fail to examine this aspect of indigenous knowledge.”

Challenges to integrating indigenous education into modern education in Ethiopia

Study participants cited potential challenges in incorporating indigenous education into modern education due to the individualistic nature of modern education, the Western model of modernization, and the Western-oriented educational backgrounds of elites.

A participant (T.7) of the study reported some elites believe that the only way to come out of poverty is with a Western model of education:

“According to Ethiopia’s contemporary elites, industrialization and progress may be facilitated by Western education and modernization that is centered on Europe”

Another participant (T.5) suggested a contradiction between the individualistic view of modern education and the community view indigenous education:

“In my perspective, the indigenous approach, which profoundly incorporates learning into the socio-cultural activities of the communities, is in contradiction to the notion of an organized curriculum constructed on a highly customised educational model.”

Another participant (T.3) noted a challenge posed by Western-oriented educational background elites:

“Integrating indigenous pedagogy into modern education may involve confronting the power, authority, and prestige of the dominant Western culture, which could pose challenges for teachers and educators with Western-oriented educational backgrounds.”

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to investigate university teachers’ perspectives on traditional and contemporary educational systems in Ethiopia, as well as the first to consider any potential integration of the two. We looked at the different viewpoints that university professors have regarding traditional and contemporary education, as well as the difficulties and potential benefits of further integrating the two systems. Teachers agreed that traditional education is distinct from other educational systems, but they disagreed on what constitutes indigenous education per se. Indeed, Ethiopia is a multicultural country with more than 80 ethnic groups, with each group having its own indigenous knowledge (Negash, 1996).

Several ancient Ethiopian knowledge-acquisition processes, as well as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and other indigenous learning institutions, were mentioned by participants. This demonstrates that one of the major shortcomings of Ethiopian indigenous education is the lack of a social-philosophical foundation, which could introduce a sense of uniformity. This result indicates that we should proceed cautiously and refrain from oversimplifying and designating all of Ethiopia’s modes of knowing as “indigenous education.”

Participants acknowledged that Ethiopian indigenous education emphasizes multimodal learning, teaching, and knowing, with a particular emphasis on knowledge transfer through close interaction and a holistic relationship between the social and physical environment. On the other hand, Western modern education follows a reductionist and mechanistic approach using the scientific method of knowledge production. For instance, in the reductionist approach, there exists a separation of humans from nature and a separation of nature from culture (Zinyeka et al., 2016). From an interpretative viewpoint, an indigenous methodology that allows for learning from additional epistemic sources was one of the multimodal indigenous knowledge production methods mentioned by participants. This is one of the study’s encouraging findings because it confirms that the Ethiopian Orthodox Church’s knowledge production was interpreted in light of the cultural context, indicating the potential for the two systems to be integrated in the future. That is, to be relevant, education should build on the worldviews of the context in which the learning happens (Owuor, 2007).

It was suggested by teachers that the educational system be changed to include a precise definitional framework based on Ethiopian worldviews. They determined that, in contrast to individualism in a Western context, collectivism was the dominant worldview in Ethiopia. The findings of this study support the idiomatic title of the study, which suggests that interactions among students, teachers, families, and community members in general are the main focus of learning opportunities in indigenous education. Through these relational systems, young people learn about the nature of relational responsibility, how to engage in communal life, and what it means to be a responsible family member and person in the world (Alcalá and Cervera, 2022).

Such perspectives correspond with a dimension of decoloniality, which emphasizes the need for pedagogies that are responsive to diverse learners and their cultural contexts. Decolonial theory encourages participatory, dialogical, and experiential approaches that engage students as active agents in their learning. This approach values community knowledge, intercultural dialog, and critical thinking to address social inequalities and injustices.

Critics of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church education system have pointed out that the techniques and contents of the system were inappropriate for developing either the understanding or cultivating the intellectual faculties of creativity, criticism, and imagination due to the heavy dependency on “the role of rote memory (Wodajo, 1959).” Some study participants, however, disagreed, instead believing that memorization is a crucial component of education that encourages the growth of creativity and long-term mental abilities. This discrepancy may perhaps be explained by rigorous poetry instruction in Ethiopian Orthodox Church teaching that makes extensive use of students’ creative and critical thinking skills. The finding that constructivist learning approaches are present in Ethiopian indigenous teaching might be a compelling reason for adapting and synthesizing the educational heritages of the country with the new needs of modern education and, subsequently, modernization. Our findings show that Ethiopia’s quick adoption of modern education was viewed as a shortcut to the kind of development that Europe only started to experience after a drawn-out and gradual process. According to the Social Darwinist theory, widely used as a theoretical support for colonial activities, societies, economics, politics, cultures, education, and religions develop in phases from simple to complex, from primitivism to civilization, from religious education to secular science, and from traditional to contemporary. A possible explanation for Ethiopia’s link between modernization and modern education is that the West is positioned at the “top” and Africa at the “bottom,” with progress being made in an upward direction. Modern education is thought to support and facilitate this social evolutionism. Study participants emphasized that Western education had improved Ethiopians’ quality of life, access to public services, and ability to amass wealth, use technology, and enjoy comforts. One would hope that formal education would allow some of the positive, both sustainable and non-sustainable, materialistic values of Western education to be passed along. However, Asgedom (2009) argues that core values are profoundly cultural in nature and therefore difficult to transfer. Such modern education, modeled after those of Western nations, was welcomed with enthusiasm by teachers who had high hopes that it would lead to much-desired economic growth for the people. Despite significant investment, interest, community support, and effort, modern education has not succeeded in achieving these goals. It is therefore not uncommon in Ethiopia to see a farmer starving to death close to an agricultural college where students study the high science of farming, or a community gripped by a malaria epidemic close to a teaching hospital. Such a tragic scenario is still present in Ethiopia and the majority of other African nations (Negash, 1996; Spring, 1998; Okrah, 2008; Asgedom, 2009).

Postcolonial theory addresses the flaws of such evolutionary logic by questioning the dominance of Western knowledge and the marginalization of indigenous knowledge systems in development processes. It argues for the inclusion and valorization of local knowledge, cultural practices, and epistemologies in shaping development agendas and policies in Africa.

Study participants concurred that Ethiopia’s current educational system needs to be replaced with a fresh approach that is deeply rooted in regional values and educational systems while also thoughtfully incorporating ideas and innovations from other parts of the world. They provided examples of possible methods for integrating indigenous education into the current educational structure. In the Ethiopian educational context, for example, the current dominant discourses around indigenous knowledge connect to a recognition of the need to address the deficiencies of development knowledge that is developed in Western contexts. It is hoped that local issues can be effectively handled with the incorporation of local knowledge that is more suitable for the needs of the indigenous communities. Since the 1970s, an increasing number of academics and United Nations organizations have focused on studying how indigenous institutions and knowledge could support more culturally appropriate and sustainable development (Dei, 2002; Ntarangwi, 2005; UNESCO, 2006). Based on our findings, because Ethiopia is a multicultural country, one approach might be to be cautious and avoid lumping the various Ethiopian ways of knowing under the category of indigenous education. According to Semali and Kincheloe (1999) and Angioni (2003), such generalization may cause these types of knowledge to become isolated from their particular contexts, which could result in their oversimplification and superficial application. The distinctive and significant contribution that specific indigenous knowledge types may be able to make to development within specific localities and among local groups who embrace such knowledge is likely to be jeopardized by such homogenization, which may even result in political instability.

Decoloniality challenges the dominance of one knowledge system in education and advocates for the recognition and inclusion of diverse knowledge systems, including indigenous and marginalized knowledge. It emphasizes the importance of epistemological pluralism, where different ways of knowing and learning are valued and integrated into the curriculum.

While the participants’ vision for the integration of the two systems is inspiring, it also highlights that the true challenges to achieving integration may be related to the theoretical divide and perception of hierarchy between traditional and modern education systems. Participants stressed the challenges of integrating indigenous education into current modern education, focusing on the individualistic nature of modern education, the Western model of modernization of the country, and the Western-oriented educational backgrounds of the Ethiopian elites. The pluralistic approach to knowledge systems, which calls for all stakeholders in education to respect the various knowledge systems and embrace their underlying logic and epistemological principles, may be the answer. According to Martin (2012), Two-Eyed Seeing holds the view that no one perspective is right or wrong; all views are seen to contribute something unique and important. As a result, conflicts between the two ways of knowing are avoided since “differences are recognized and embraced.” A Two-Eyed Seeing approach seeks to avoid knowledge domination and assimilation by recognizing the best from both worlds (Hatcher et al., 2009). Postcolonial theory furthermore acknowledges the hybridity of African societies, which emerged through the mixing of indigenous and colonial education. It emphasizes the agency of African individuals, communities, and social movements in challenging dominant development paradigms, reclaiming indigenous education, and asserting alternative visions of development rooted in local realities.

Conclusion and recommendation

This qualitative study provides valuable insights into the perspectives of university teachers regarding traditional and contemporary educational systems and the potential integration of the two. It is never simple to make radical changes to modern education in Ethiopia. However, there is a fresh opportunity for challenging previously unshakable and unchallenged beliefs. The modern educational systems, which up until now have not been thoroughly questioned, if at all, must be examined. The higher education system in low-income countries urgently requires this. To inform educational policies and practices on the fusion of traditional and modern education, higher education research in Africa should offer evidence-based recommendations. The creation of inclusive policies that acknowledge and promote the significance of indigenous education within the continent’s mainstream educational systems should be guided by research findings.

There is no doubt that the transformation of Ethiopia requires more than what indigenous education has to offer. But it also requires more than what modern education provides. The descriptions of indigenous knowledge provided by the participants highlight Ethiopia as a diverse country, a distinguishing strength that rejects the one-size-fits-all foreign education reform intended to mute local knowledge. Therefore, Ethiopia’s current communal cultural wealth has to be seriously taken into account in all aspects of education reform if the country is to make significant educational advancements. Knowledge should not be limited to the norms and epistemologies of the Western viewpoint but rather respected for its diversity. Decoloniality and postcolonial theories emerge as important frameworks for reevaluating dominant knowledge systems and promoting inclusivity in education. The study participants advocate for the integration of indigenous knowledge and indigenous epistemologies into the educational system. Integrating modern and indigenous education based on the Two-Eyed Seeing theory in Ethiopia brings many advantages, including the preservation of indigenous knowledge, holistic education, cultural identity, contextualised learning, sustainable development, and community engagement. However, challenges such as the marginalization of indigenous knowledge due to the individualistic nature of modern education, resistance from elites with Western-oriented educational backgrounds, and the undervaluation of indigenous knowledge must be overcome to successfully integrate these educational approaches in Ethiopia.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Addis Ababa University College of Health Sciences, School of Medicine IRB. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. CW: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Erin Saunders for her editing assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alatas, S. F. (2006). From Jāmi’ ah to university: multiculturalism and Christian–Muslim dialogue. Curr. Sociol. 54, 112–132. doi: 10.1177/0011392106058837

Alcalá, L., and Cervera, M. D. (2022). Yucatec Maya mothers’ ethnotheories about learning to help at home. Infant Child Dev. 31:e2318. doi: 10.1002/icd.2318

Angioni, G. (2003). “Indigenous knowledge: subordination and localism” in Nature, knowledge: Ethnoscience, cognition, and utility. eds. G. Sanga and G. Ortalli (New York: Oxford University Press)

Asgedom, A. (2005). Higher education in pre-revolution Ethiopia: relevance and academic freedom. In the Ethiopian. J. High. Educ. 2, 1–45.

Asgedom. (2009). Yekefitegna timhirt sireate timihirt agibabinetna yememaria gibeatoch yizota [the suitability and the state of teaching inputs in the curriculum for higher education].

Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA). (2006). Indigenous knowledge and education in Africa. Available at: http://www.adeanet.org/en/system/files/indigenousknowledgeandeducationinafrica.pdf

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., and Marshall, A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2, 331–340. doi: 10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK: Purich Publishing Limited.

Dei, S. G. J. (2002). “African development: the relevance and implications of indigenousness” in Indigenous knowledges in global contexts: Multiple readings of our world. eds. G. J. S. Dei, B. L. Hall, and D. G. Rosenberg (Toronto: University of Toronto Press)

Dei, G. J. S. (2004). Schooling & education in Africa: the case of Ghana. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Dreijmanis, J., and Wagaw, T. G. (1996). The development of higher education and social change: an Ethiopian experience. Afr. Stud. Rev. 39:184. doi: 10.2307/525456

Federal Democratic Republic Government of Ethiopia. (1994). Education and training Policy AA, First edtion. St. George Printing. 2.

Federal Ministry of Education. (2021). Education sector development Programme VI (ESDP VI). Available at: https://assets.globalpartnership.org/s3fs-public/document/file/2021-11-education-sector-development-plan-ethiopia.pdf?VersionId=eCE8EO7S11XRa806tewLkhRcQfQ6yU2B

Forbes, A., Ritchie, S., Walker, J., and Young, N. (2020). Applications of two-eyed seeing in primary research focused on indigenous health: a scoping review. Int J Qual Methods 19:2911. doi: 10.1177/1609406920929110

Gemechu, E. (2016). Quest of traditional education in Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Res. J. Educ. Sci. 4, 1–5.

Gregory, C. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of indigenous education 1st. Rio Rancho NM: Kivakí Press.

Grigorenko, E. L. (2007). Hitting, missing, and in between: a typology of the impact of western education on the non-western world. Comp. Educ. 43, 165–186. doi: 10.1080/03050060601162719

Hatcher, A., Bartlett, C., Marshall, A., and Marshall, M. (2009). Two-eyed seeing in the classroom environment: concepts, approaches, and challenges. Can. J. Sci. Math. Technol. Educ. 9, 141–153. doi: 10.1080/14926150903118342

Heleta, S. (2016). Decolonisation of higher education: dismantling epistemic violence and eurocentrism in South Africa. Transformation. High. Educ. 1, 1–8. doi: 10.4102/the.v1i1.9

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York, London: Routledge.

Kassaye, W. (2005). An overview of curriculum development in the different periods of Ethiopia: 1908-2005. Ethiop. J. Soc. Sci. Human. 3, 49–80. doi: 10.4314/ejossah.v3i1.29871

Kaya, H. O., and Seleti, N. (2013). African indigenous knowledge systems and relevance of higher education in South Africa. Int. Educ. J. Comp. Perspect. 12, 30–44.

Keenleyside, H. L., and Thomas, A. F. (1937). History of japanese education and present educational system. Tokyo: Hokuseido Press. Hokuseido Press.

Kelman, I., Mercer, J., and Gaillard, J. (2012). Indigenous knowledge and disaster risk reduction. Geography 97, 12–21. doi: 10.1080/00167487.2012.12094332

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: contributions to the development of a concept. Cult. Stud. 21, 240–270. doi: 10.1080/09502380601162548

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., and Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 26, 1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444

Mamdani, M. (2007). Scholars in the marketplace: The dilemmas of neo-liberal reform at Makerere University, 1989–2005. Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa.

Martin, D. H. (2012). Two-eyed seeing: a framework for understanding indigenous and non-indigenousa pproaches to indigenous health. Research 44, 20–42.

Mawere, M. (2015). Indigenous knowledge and public education in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr. Spectr. 50, 57–71. doi: 10.1177/000203971505000203

Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The darker side of Western modernity: Global futures decolonial options, Durham: Duke University Press.

Milkias, P. (1976). Traditional institutions and traditional elites: the role of education in the Ethiopian body-politic. Afr. Stud. Rev. 19:79. doi: 10.2307/523876

Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1986). Decolonizing the mind: the politics of language in African literature. J. Currey Heinemann Kenya

Ntarangwi, M. (2005). The challenges of education and development in post-colonial Kenya. Afr. Dev. 28, 211–228. doi: 10.4314/ad.v28i2.22183

Okrah, K. A. (2008). The African Symposium: An Online Journal of African Educational Research Network. Sankofa: cultural heritage conservation and sustainable African development 8, 24–31. Available at: https://services.spalding.edu/ncate/files/2011/02/TAS82.pdf#page=24.

Owuor, J. A. (2007). Integrating African indigenous knowledge in Kenya’s formal education system: the potential for sustainable development. J. Contemp. Issues Educ. 2, 21–37.

Pankhurst, R. (1972). Education in Ethiopia during the Italian fascist occupation (1936-1941). Int. J. Afr. Hist. Stud. 5:361. doi: 10.2307/217091

Roher, S. I. G., Yu, Z., Martin, D. H., and Benoit, A. C. (2021). How is Etuaptmumk/two-eyed seeing characterized in indigenous health research? A scoping review. Plos One 16:e0254612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254612

Semali, L. M., and Kincheloe, J. L. (1999). What is indigenous knowledge? Voices from the Academy. London: Routledge.

Serbessa, D. D. (2006). Tension between traditional and modern teaching-learning approaches in Ethiopian primary schools. J. Int. Cooperat. Educ. 9, 123–140. Available at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:17970512.

Sisay, A. W. (2017). Historical development, existing challenges and opportunities in Ethiopian education. J. Afr. Stud. Dev. 9, 89–101. doi: 10.5897/JASD2016.0411

Sleeter, C. E. (2012). Confronting the marginalization of culturally responsive pedagogy. Urban Educ. 47, 562–584. doi: 10.1177/0042085911431472

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. 2nd Ed. London and New York: University of Otago Press, Zed Books.

Stein, S., Andreotti, V., Suša, R., Amsler, S., Hunt, D., Ahenakew, C., et al. (2020). Gesturing towards Decolonial futures: reflections on our learnings thus far. Nordic J. Comp. Int. Educ. 4, 43–65. doi: 10.7577/njcie.3518

Team, G and Initiative, N (2014). Teaching and learning: achieving quality for all; EFA global monitoring report, 2013-2014; gender summary (ara). UNESCO; ED-2014/SANS COTE, ED-2014/WS/15. Available at: CID: 20.500.12592/cfth10. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/8192442/teaching-and-learning/9102757/.

Teferra, T., Asgedom, A., Oumer, J., Whanna, T., Dalelo, A., and Assefa, B. (2018). Ethiopian education development roadmap (2017–30) an integrated executive summary.

Tyler, R. W. (1949). The basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

UNESCO. (2003). Traditional African modes of education: their relevance in the modern world. Available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001393/139369e.pdf

UNESCO. (2006). Strategy of education for sustainable development in sub-Saharan Africa. Dakar: UNESCO Regional Office for Education in Africa: UNESCO/BREDA.

Weiler, V. (2001). Knowledge, politics, and the future of higher education: critical observations on a worldwide transformation.In R. Hayhoe and J. Pan (Eds.), Knowledge across culture: A contribution to the dialogue among civilisations. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong.

Wright, A. L., Gabel, C., Ballantyne, M., Jack, S. M., and Wahoush, O. (2019). Using two-eyed seeing in research with indigenous people: an integrative review. Int. J. Qual. Methods 18:6969. doi: 10.1177/1609406919869695

Keywords: indigenous education, modern education, integration, higher education, Ethiopia

Citation: Baheretibeb Y and Whitehead C (2024) “It takes a village to raise a child,” university teachers’ views on traditional education, modern education, and future I integration in Ethiopia. Front. Educ. 9:1348377. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1348377

Edited by:

Raúl Ruiz Cecilia, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Milan Kubiatko, J. E. Purkyne University, CzechiaManuel J. Cardoso-Pulido, University of Granada, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Baheretibeb and Whitehead. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yonas Baheretibeb, yonas.baheretibeb@aau.edu.et

Yonas Baheretibeb

Yonas Baheretibeb Cynthia Whitehead2

Cynthia Whitehead2