Abstract

Clinical features of COVID-19 have been mostly described in hospitalized patients with and without ICU admission. Yet, up to 80% of patients are managed in an outpatient setting. This population is poorly documented. In France, health authorities recommend outpatient management of patients presenting mild-to-moderate COVID-19 symptoms. The aim of this study was to describe their clinical characteristics. The study took place in an emergency medical dispatching center located in the Greater Paris region. Patients included in this survey met confirmed COVID-19 infection criteria according to the WHO definition. We investigated clinical features and classified symptoms as general, digestive, ear–nose–throat, thoracic symptoms, and eye disease. Patients were included between March 24 and April 6 2020. 1487 patients included: 700 (47%) males and 752 (51%) females, with a median age of 44 (32–57) years. In addition to dry cough and fever reported in more than 90% of cases, the most common symptoms were general symptoms: body aches/myalgia (N = 845; 57%), headache (N = 824; 55%), and asthenia (N = 886; 60%); shortness of breath (N = 479; 32%) and ear–nose–throat symptoms such as anosmia (N = 415; 28%) and ageusia (N = 422; 28%). Chest pain was reported in 320 (21%) cases and hemoptysis in 41 (3%) cases. The main difference between male and female patients was an increased prevalence of ear–nose–throat symptoms as well as diarrhea, chest pains, and headaches in female patients. General symptoms and ear–nose–throat symptoms were predominant in COVID-19 patients presenting mild-to-moderate symptoms. Shortness of breath and chest pain were remarkably frequent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many papers have described the COVID-19 patient population [1, 2]. The majority have reported clinical features in hospitalized with or without ICU admission, mostly in China and more recently in Italy [3, 4]. Yet, most of the patients in these countries were managed in an outpatient setting. This population has been excluded of the studies and its characteristics are poorly documented.

In France, health authorities were quick to recommend outpatient management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection who presented with mild-to-moderate symptoms. Patients were asked to contact the emergency medical system (SAMU) with their questions and in the event of worsening symptoms. SAMU can be reached with a single national toll-free number, nationwide, ‘15’ [5]. Since the beginning of the epidemic in Europe at the end of February, the number of calls increased dramatically, up to 400% of normal call volume. After an initial assessment by an EMS regulator, patients with less severe symptoms were not immediately connected to the emergency physician dispatcher, but received a follow-up telephone call within the following 12 h. This is the patient cohort studied here. The aim of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics of a large cohort of COVID-confirmed patients managed in outpatient settings, and to compare this clinical feature with previously published features.

Methods

Site

The study took place in SAMU 93 emergency medical dispatching center located in the Seine-Saint-Denis district of the Greater Paris, north-east of Paris proper. This district encompasses a population of 1.6 million for an area of 236 km2, making it one of the most densely populated districts in France; it is also the most socioeconomically disadvantaged district. Our call center received 750,000 calls in 2019, resulting in the management of 250,000 patients.

Procedure

During the study period, patients were included in our prospective observational survey if they met confirmed COVID-19 infection criteria according to the WHO definition, i.e., positive PCR or fever (during the last 48 h) and dry cough (https://www.who.int). We investigated clinical features and classified symptoms as general symptoms (body aches/myalgia, headache, and asthenia), digestive symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), ear–nose–throat symptoms (pharyngalgia, rhinopharyngitis, anosmia and ageusia), respiratory and chest symptoms (shortness of breath, chest pain, and hemoptysis), and eye disease. Finally, the decision whether or not to transfer the patient to the hospital was recorded. As patients were asked to call back the SAMU in case of worsening symptoms, only the first call was considered an inclusion criterion. Patients were included between March 24 and April 6.

Analysis and ethics

Our primary aim was to compare clinical features of COVID-19 infection in male and female patients. We also compared clinical features based on the main inclusion criteria, positive PCR vs clinically confirmed COVID-19.

The aim was to include 1500 consecutive patients. The management of the patients was not affected by the study. According to French law, the study was recorded at the Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté (CNIL 1881609), the French national data protection authority. Qualitative date was compared using a Chi-square test; quantitative date was compared using a Student T test. A p value < 0.05 was considered as significant. Results are expressed as N (%) or median (IQ). Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.6.3.

Results

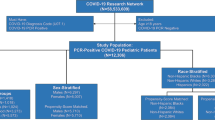

During the study period, 5104 patients were screened as having no signs of severity and 1487 (29%) were included: 700 (47%) patients were male and 752 (51%) were female (missing data: N = 35) with a median age of 44 (32–57) years. Among these patients, 28 (2%) were aged under 16 years and 12 (1%) under 10. COVID-19 infection was diagnosed according to clinical symptoms (fever + cough) in 1351 (91%) cases and according to PCR test in 197 (13%) cases.

In addition to dry cough and fever (inclusion criteria) reported in more than 90% of cases, the most common symptoms were general symptoms: body aches/myalgia (N = 845; 57%), headache (N = 824; 55%), asthenia (N = 886; 60%); ear–nose–throat symptoms such as anosmia (N = 415; 28%), ageusia (N = 422; 28%), ageusia and anosmia (N = 335; 23%), and shortness of breath (N = 479; 32%). Chest pain was reported in 320 (22%) cases and hemoptysis in 41 (3%) cases. Complete results are reported in Fig. 1. The main difference between male and female patients was the prevalence of ear–nose–throat symptoms (Table 1). Chest pain and headaches were also more frequent in female patients.

After assessment by phone, 83 (6%) patients were transferred to the hospital, without significant difference in terms of gender.

Results of the comparison between clinical features in patients with positive PCR and those with clinically confirmed COVID-19 are reported in the Supplementary Annexes. Patients with positive PCR were younger and complained less frequently of body aches and asthenia and more frequently of vomiting and shortness of breath.

Discussion

The clinical features of COVID-19 infection in this large cohort of patients managed in outpatient settings were extremely varied. As previously reported, general symptoms, i.e., flu-like symptoms such as fever, cough, and asthenia, and body aches and headaches were the most frequent symptoms. Female patients were more likely to present ear–nose–throat symptoms, chest pain, and headaches than male patients.

Our first aim was to describe the symptoms observed in patients who received outpatient care. We were able to complete this goal, as only 5% of patients were transferred to the hospital after medical evaluation by the emergency physician dispatcher. As 80% of COVID-19 patients worldwide are managed in outpatient settings, we postulate that the clinical features described here apply to most COVID-19 patients. Consequently, in our study, sex ratio is close to the global population. It contrasts with the in-hospital patient population which is predominantly male in ICU and other hospital departments [4, 6,7,8].

Anosmia and ageusia have become cardinal signs of COVID-19, but these symptoms were under-reported in the first papers from China. Its prevalence was higher in our findings than previously reported in Chinese and Italian papers, which report these symptoms in 5–6% and 19% of cases, respectively [9, 10]. These symptoms appear to be more prevalent in patients presenting mild-to-moderate symptoms [11]. The physiopathology of anosmia and ageusia is still unclear. As this symptom is infrequent in clinical practice, it should be considered a sensitive diagnostic criterion [10].

A few recent papers have described the clinical features of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in hospitalized patients [12,13,14]. General symptoms such as anosmia, asthenia, headaches, and myalgia were the most frequently reported symptoms. A score based on these symptoms has been proposed [13].

Chest pain was frequent, occurring in 20% of cases, and can be explained by pulmonary disease and severe coughing. However, specific injuries such as pericarditis and myocarditis as well as pulmonary embolism have been found [15,16,17]. Cardiovascular complications seem to be largely involved in critical outcome [18]. Nevertheless, we currently are unsure of the relevance of investigating chest pain with electrocardiogram and echocardiography in paucisymptomatic patients. Moreover, due to the high prevalence of chest pain, it was unrealistic to propose systematic investigations.

Hemoptysis was not uncommon. Recent emergency medicine papers on pulmonary embolisms, which is the most frequent cause of hemoptysis in emergency medicine, reveal that hemoptysis occurred in 2–8% of pulmonary embolisms [19, 20].

Limitations

The main limit of this study is the lack of definitive COVID infection confirmation by RT-PCR. However, we based ourselves on the WHO’s inclusion criteria. The second limit is the lack of clinical assessment. Symptoms were reported by patients and not directly recorded by a physician. Due to the overload of the emergency medical system, we opted to employ this more realistic strategy. For this reason, we decided to manage these patients at home, in an outpatient setting. The third limit is the lack of follow-up. For similar reasons, this was not feasible.

Conclusion

In this original and large cohort of confirmed COVID-19 patient population managed in outpatient settings in the greater Paris area, symptoms were different from those previously reported. Digestive and ear–nose–throat symptoms were frequent.

References

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z et al (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Lond Engl 28395(10229):1054–1062

Bedford J, Enria D, Giesecke J, Heymann DL, Ihekweazu C, Kobinger G et al (2020) COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet Lond Engl 395(10229):1015–1018

Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A et al (2020) Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA 323:1574–1581

Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, Liang W-H, Ou C-Q, He J-X et al (2019) Clinical Characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 382:1708–1720

Adnet F, Lapostolle F (2004) International EMS systems: France. Resuscitation 63(1):7–9

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323:1061–1069

Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S et al (2020) Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med e200994

Han R, Huang L, Jiang H, Dong J, Peng H, Zhang D (2020) Early clinical and CT manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1–6. https://www.ajronline.org/doi/full/10.2214/AJR.20.22961

Vaira LA, Salzano G, Deiana G, De Riu G (2020) Anosmia and ageusia: common findings in COVID-19 patients. Laryngoscope. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28692

Mao L, Wang M, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C et al (2020) Neurological Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.22.20026500v1

Iacobucci G (2020) Sixty seconds on.. anosmia. BMJ 368:m1202

Tostmann A, Bradley J, Bousema T, Yiek W-K, Holwerda M, Bleeker-Rovers C et al (2020) Strong associations and moderate predictive value of early symptoms for SARS-CoV-2 test positivity among healthcare workers, the Netherlands, March 2020. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull 25(16):2000508

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Place S, Van Laethem Y, Cabaraux P, Mat Q et al (2020) Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of 1,420 European Patients with mild-to-moderate Coronavirus Disease 2019. J Intern Med

Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C (2020) Mild or Moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med

Akhmerov A, Marban E (2020) COVID-19 and the Heart. Circ Res 126(10):1443–1455

Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, Cai Y, Liu T, Yang F et al (2020) Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol e200950

Han H, Xie L, Liu R, Yang J, Liu F, Wu K et al (2020) Analysis of heart injury laboratory parameters in 273 COVID-19 patients in one hospital in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25809

Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ 368:m1091

Morrone D, Morrone V (2018) Acute pulmonary embolism: focus on the clinical picture. Korean Circ J mai 48(5):365–381

Miniati M, Cenci C, Monti S, Poli D (2012) Clinical presentation of acute pulmonary embolism: survey of 800 cases. PLoS ONE 7(2):e30891

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to: the conception and design of the study (FL, FA), acquisition of data (DG, RB, BJ, MJ, GL, CE), analysis and interpretation of data (SE, FL) drafting the article (FL), revising it critically for important intellectual content (FA, VI, PT); final approval of the version to be submitted (LF, SE, VI, DG, RB, BJ, MJ, GL, CE, PT, AF).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

LF: Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, Medtronic, Merck-Serono, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Serb, Teleflex, The Medicine Company and other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

The study was recorded and conducted according to the rules of the French National Committee for Informatic and Liberty (CNIL 1881609).

Informed consent

In this study, formal consent was not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lapostolle, F., Schneider, E., Vianu, I. et al. Clinical features of 1487 COVID-19 patients with outpatient management in the Greater Paris: the COVID-call study. Intern Emerg Med 15, 813–817 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-020-02379-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-020-02379-z