Ronnie O'Sullivan: The Da Vinci of the baize

-

Published

-

comments

Most sport involves men and women wrestling with their craft. It is a struggle for mastery, a struggle for separation. Like most of life, it is humdrum and mundane. But a chosen few are able to elevate their sport into an intoxicating blend of science and art. Like Ronnie O'Sullivan, the Da Vinci of the baize.

Watching his 6-0 victory over poor Ricky Walden in the quarter-finals of the Masters, former world champion John Parrott noted that a fireworks display would not have broken O'Sullivan's concentration.

On the contrary, when O'Sullivan is in this sort of form, tournament organisers should make sparklers and a few bars of Handel obligatory for every one of his breaks.

To some, the suggestion there is beauty in what O'Sullivan does will seem preposterous.

When the ancient Greeks conflated sport and beauty, they probably didn't have in mind a man striding around a table hitting balls with a stick. But this is O'Sullivan's real genius, the ability to make a devilishly difficult stationary ball game such as snooker look lithe and athletic.

For most snooker players, breaks represent long, hard yomps over dangerous terrain. They overcome obstacles and perform nerve-jangling escapes before surveying the landscape under knitted brows and setting off again.

For O'Sullivan last week at Alexandra Palace, breaks were more serene affairs. Obstacles melted before him, enemies scattered. So by the time O'Sullivan wrapped up a 10-4 victory over Mark Selby in the final, white flags were being waved and the great and good of snooker were lining up to pay tribute.

When O'Sullivan plays snooker like this, the consensus is that he makes it look like he is playing another game. This is what the beautiful sportspeople do.

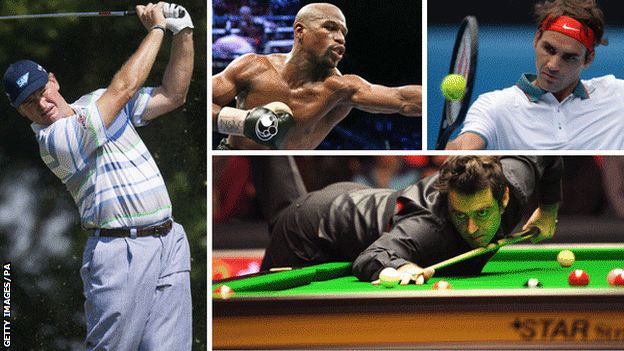

In the hands of Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal and Andy Murray, a tennis racquet is a rock hammer and a tennis court a quarry. In the hands of Roger Federer, a tennis racquet is a paint brush and a tennis court a canvas.

To look effortless in the ultra-competitive, brutally scientific and often formulaic world of modern professional sport takes some doing. Even Federer, with 17 Grand Slam singles titles behind him, is beginning to look a bit quaint.

Roger Federer's artistry looked effortless at times, and brought him a record 17 Grand Slam titles

But even in the brutal world of boxing, there are some who are able to look both sweet and scientific. The beauty of Floyd Mayweather is that he manages to make the almost impossible - hitting without being hit - look simple. But perhaps boxing's greatest beauty was Mayweather's fellow American Pernell Whitaker, who won world titles at four different weights in the 1980s and 90s.

"Whitaker's moves," wrote boxing historian Bert Sugar, "were pure poetry in motion. Or, more correctly, pure poetry in many motions. Whitaker did for boxing what Edgar Degas did for ballerinas and Vincent van Gogh for sunflowers." In truth, what Whitaker did defied description. Get on YouTube and see for yourself.

Whitaker was able to appear weightless in the most oppressive situations. He made fellow legends - Oscar de la Hoya and Julio Cesar Chavez among them - look like they were plodding after him in diver's boots. Just as Sebastian Coe, British middle-distance running's most soothing virtuoso, was able to do.

Whereas his rivals would invariably enter the home straight looking like runaway barrels, Coe would round the bend looking like he was attached to rails. Steve Ovett made running look fun but Coe made it look artistic.

In cricket, much has been written about the beautiful batsmen and their flashing blades, such as David Gower and Brian Lara. But perhaps the most beautiful sight was former West Indies fast bowler Malcolm Marshall.

Dan Carter's poise and grace under pressure stands out in an intensely physical sport

Most quicks clatter towards the wicket and release the ball amid a cacophony of limbs. Marshall skimmed towards the crease like a pebble across a pond, while his delivery was all part of the same, fluid movement. Getting hit in the face by Marshall must have been like being the recipient of an extremely rough kiss.

To look effortless, and therefore beautiful, in a genuine team sport like football is more difficult to do. A football match is essentially a series of puzzles - weigh-up what's on, receive the ball, assess patterns, distance and angles.

Given the added pressure of harrying opponents and baying fans, some minds implode. Others muddle through. But a few beautiful minds take the cryptic route, solving puzzles that only they know existed in the first place.

But to be beautiful in a sport as violent and cluttered as rugby union is another thing. Very few manage it, but New Zealand fly-half Dan Carter is one of them. The concept of game-management doesn't sound too sexy. But Carter manages a game like a conductor in charge of an orchestra under heavy shelling.

The All Black is the most complete fly-half in modern rugby but beauty in sport is not necessarily about being the best. On his day, Tiger Woods plays golf better than anyone but he often makes it look as pleasing to the senses as shovelling coal.

Woods is the man to win a match on which your life depended but you would take Ernie Els with you to a desert island, along with his clubs and a lifetime's supply of balls. "Play it again, Ernie… and again and again and again…"

As a fan, sometimes you want to see a sportsperson elevating their craft rather than wrestling with it. Even if, as with Woods, a particular sportsperson possesses the unerring ability to wrestle their craft into submission.

O'Sullivan on song is above anything as vulgar as wrestling, separate from the humdrum and mundane. He strides around a table hitting balls with a stick. But, as preposterous as it seems, sport has rarely looked so beautiful.

-

-

Published17 January 2014

-

-

-

Published20 January 2014

-

-

-

Published19 January 2014

-

-

-

Published6 May 2013

-

-

-

Published20 January 2014

-