The rain was teeming down in Bern and Hungary were about to win the World Cup. Ferenc Puskas had put the Mighty Magyars ahead after six minutes and Zoltan Czibor had doubled the advantage after eight. They were 2-0 up inside 10 minutes and they had not lost in four years. They were 2-0 up inside 10 minutes against a team that they had beaten 8-3 barely a fortnight earlier. They were 2-0 up inside 10 minutes against a side who, four years earlier, did not even exist.

What unfolded over the next 80 minutes, if you subscribe to the more romantic interpretations, created one country and fanned the flames of a revolution in another. Even the most mundane reading of events would still need to use the phrase “greatest comeback ever seen in a World Cup final”. Hungary were 2-0 up inside 10 minutes but it was West Germany who were about to win the World Cup.

West Germany’s road to Switzerland

In the inter-war period, German football had been among the strongest in Europe. In 1934 the Mannschaft had finished third at the World Cup, beating the Austrian Wunderteam in the third-place play-off. Three years later Sepp Herberger’s Breslau Elf – monikered after the side who defeated Denmark 8-0 in Breslau – went 11 games undefeated (winning 10) but by 1938 the Anschluss had created a “united” German side that was anything but and the World Cup campaign that year ended at the first hurdle with defeat to the Swiss.

Then came war. Football became propaganda. The continuing league system was held up by the Nazi regime as “proof of morale”. Throughout the conflict Herberger, who had been in sole charge of the national side since 1936, would do his best to keep his charges out of harm’s way. When passes back from the front became available only to those decorated in service, the national team manager would falsify documents in order to get his players. And he would do what he could to install members of his squad in positions away from the fronts. Several, Herberger’s golden boy Fritz Walter among them, were wangled comparatively safe jobs at an airforce base, which also just happened to have one of the best football sides in the country.

But Herberger’s best efforts were not enough amid the carnage. For example Adolf Urban, Schalke’s star striker who had made his debut for the interntional side in 1935 aged only 21 and was a member of the Breslau Elf, helped his club side to a league triumph in 1942, then played in their cup final defeat to 1860 Munich. It was his last ever game – after the final he was posted to Stalingrad and, like almost 2,000,000 others on both sides, never returned home.

International matches had finally ceased in February 1943 on the orders of Joseph Goebbels and his plans for “total war”. Club football ground to a halt in August 1944. In the immediate aftermath of the war, with Germany quartered among the victors, old sporting clubs were banned, and large assemblies of people were outlawed. The ability of footballers to play depended on which zone they found themselves in. Gradually, though, teams reformed or formed anew, with the bigger ones travelling the country taking on smaller sides in exchange for fuel or food. A nascent league system was quickly back in place but it was July 1949 before the German FA, the DFB, came back into being. In February 1950 a West German national side was reformed under the auspices of Herberger, who survived the post-war process of denazificartion despite having been a member of the party since 1933, once more. In September the country was admitted to Fifa and in November West Germany played their first post-war international against Switzerland in Stuttgart. Herberger’s side won 1-0.

That result did not exactly herald the birth of a new footballing superpower. Defeats against Turkey and Ireland put Herberger under pressure and they began the qualifying campaign for the 1954 World Cup with a 1-1 draw in Oslo against Norway. The crunch game came in Saarbrucken against the newly independent Saarland and a 3-1 win was enough to take Herberger and his side to the finals.

Hungary’s road to Switzerland

“For the first half of the 20th century, both from a footballing and a political point of view, Hungary had existed in the shadow of Austria,” writes Jonathan Wilson in Inverting the Pyramid. “Their thinking had, inevitably, been influenced by Hugo Meisl and the Danubian Whirl, but the crucial point was that it was thinking. In Budapest, as in Vienna, football was a matter for intellectual debate.”

Like Germany, Hungary had been a powerful pre-war footballing presence. They won Olympic gold in 1912 and were beaten finalists at the 1938 World Cup. Like Germany, international football had continued during the second world war until the end of 1943 and in the four years after VE Day, a golden generation emerged.

“The Hungarian game has always been built on or round outstanding individuals,” wrote Willy Meisl in 1956, and by the 1954 World Cup Hungary had an entire team of them. The half-dozen players at the core of the Aranycsapat – the Golden Squad – were all in the side by 1949: Ferenc Puskas and Nandor Hidegkuti made their international bows in 1945, the goalkeeper Gyula Grosics and defender Jozsef Bozsik in 1947, Sandor Kocsis in 1948 and Zoltan Czibor in 1949. Gusztav Sebes, who took sole control of the national side in the same year, had five of that six under his charge at Honved, with only Hidegkuti playing his club football elsewhere.

But even with that group in the side, Hungary were by no means on course for World Cup glory. A defeat in Prague against Czechoslovakia in 1949 proved the final straw. “After that game the issue could no longer be avoided,” wrote Puskas in his autobiography. “Hungary had to evolve an entirely new method of play if we were to make any headway in international football.” And that they did, producing a remarkably fluid structure. “Players ... constantly changed position according to a prearranged plan,” wrote Puskas. “The result was that our opponents could not guess our plans and found themselves in difficulties which would not have been experienced had we followed the usual English method of play.”

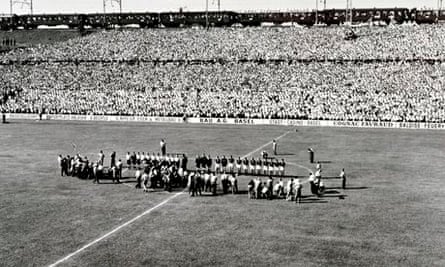

The abandonment of “the usual English method of play” meant Hungary played without the traditional battering ram No9 and instead had first Peter Palotas and, from 1952, Hidegkuti wearing No9 but playing as a trequartista. The results were extraordinary. Between June 1950 and the start of the 1954 World Cup the Mighty Magyars played 30 times without defeat, claiming a second Olympic gold medal in the process. The train that carried the side on the final leg of their journey back to Budapest after glory in Helsinki was stopped at every station by ecstatic crowds and in the capital 400,000 people lined the streets to greet them.

And while Germany laboured against Norway and Saarland, Hungary qualified for the 1954 tournament without playing a game, Poland withdrawing from their two-team qualifying group without a ball being kicked.

Then on 25 November 1953, Hungary’s Golden Squad visited Wembley to face England. The visitors won 6-3 becoming the first overseas team to win at the national stadium and changing forever English football’s perception of itself. Just for good measure they hammered Walter Winterbottom’s side 7-1 in Budapest in their final warm-up match before the 1954 tournament. Hungary were ready to take on the world. And the world expected to lose.

Round one

Group Two saw Hungary and West Germany pitted against Turkey (who had qualified for the tournament courtesy of a drawing of lots following a play-off draw against Spain) and a fairly dismal South Korea team who had reached Switzerland by virtue of a win and a draw against Japan in their two-team qualifying group. In typically bonkers Fifa style, odd rules meant that the two seeded teams – Hungary and Turkey (the seedings, again with the rational thinking we’ve come to expect from football’s governing body, having already been set before Turkey’s play-off with Spain) – would not face each other, but play only against the two unseeded sides with the top two sides reaching the knockout stages. If second and third ended level on points would – regardless of goal difference – then play each other in a play-off.

Confused? It sounds a muddle, and it was, but Herberger saw the road ahead with clarity. Defeat against Hungary was a certainty, he figured, as was a Turkish victory over the Koreans. His side would, then, need to beat Turkey in their opening game and then again in a play-off if they were to reach the knockout stages.

The plan worked perfectly, despite a shaky start. Turkey took a second-minute lead in the Wankdorf Stadium in the opening game but Hans Schäfer equalised and three second-half goals gave Herberger’s side the result they needed. Meanwhile in Zurich, Hungary dispatched the hapless Koreans 9-0, with Kocsis grabbing a hat-trick. “It was more than inexplicable how the Korean team had been admitted,” wrote Puskas. “They were very weak and had had no training.”

Turkey would have similarly little trouble and beat South Korea 7-0 in Geneva, while West Germany and Hungary were taking part in one of the most extraordinary and controversial group games in any World Cup. Herberger, with one eye on the play-off and the other, perhaps, on keeping the true strength of his side under wraps, named only four of the side who had played in the opening game. Hungary battered them, Kocsis scoring four in an 8-3 win. But the most significant incident in the game befell Puskas.

The inside-left was enjoying himself immensely against the reshuffled German side. “I could feel the ball as a violinist feels his instrument,” he writes. Jupp Posipal could not get near him, so he switched positions with Werner Liebrich. “But even against him I played like a bird on the wing.” Liebrich, though, would finally clip those wings, a crunching tackle (with the score at 5-1) causing a hairline fracture of Puskas’s ankle.

Hungary would have to cope without the Galloping Major in their quarter-final against Brazil, but West Germany were still to get there. Back to full strength, though, they had little trouble in their play-off against Turkey – a 7-3 win set up a last-eight tie against Yugoslavia.

The Miracle of Bern

Hungary reached the semis thanks to a 4-2 win in a bruising encounter with Brazil – “They behaved like violent enemies without respect for our physical safety,” reckoned Puskas from his vantage point in the stands – while Germany squeezed past 1952 Olympic silver medallists Yugoslavia 2-0. In the last four, Hungary, again without Puskas, led the reigning champions Uruguay 2-0 with 15 minutes to go only to be pegged back to 2-2 before winning 4-2 in extra time. There was no such drama for Herberger and his side, a 6-1 thrashing of Austria, who had beaten the host nation 7-5 in the quarters, taking West Germany into the final.

For the German captain it would be only the second most important game he had ever played against Hungary. Back in 1945 as Germany collapsed to defeat, Fritz Walter and his airforce base surrendered to the Americans. But they were then handed over to the Russian army and shipped to Siberia, where awaited almost certain death, a journey made by 40,000 German prisoners of war. On the way, Walter’s convoy stopped at a Ukrainian detention centre. The camp police were playing a match. Walter watched from the sidelines, flicked a stray ball back into play and was soon brought into the game. One of the guards recognised him from a friendly Germany had played in Budapest in 1942. The next day Walter’s name was removed from the list of those heading east and he was permitted to return to his home in Kaiserslautern.

Nine years later he led his team out for the World Cup final as the rain came down in Bern. The weather, and the boggy pitch, would play into his team’s hands. The German side were wearing a revolutionary new piece of kit – boots with screw-in studs that could be altered depending on the conditions.

But those boots were little help in the opening exchanges. After six minutes Liebrich made a certain amount of amends for his tackle in the group game, giving the ball straight to Bozsik 40 yards from goal. He fed Kocsis, whose shot cannoned of a German defender and fell to Puskas who poked the ball home from close range. Two minutes later, Werner Kohlmeyer, under pressure from Kocsis, and his goalkeeper Toni Turek got themselves into an almighty tangle in the box. Czibor scooted away and popped the ball into the empty net – 2-0. Another 8-3 was on the cards.

And cue miracle. On 10 minutes Helmut Rahn found space on the left and slung in a low cross. Jozsef Zakarias could only get a toe to the ball and Max Morlock slid the ball home. 2-1. Eight minutes later Fritz Walter slung in a corner, Grosics flapped, and Rahn, thundering in at the back post, slammed in West Germany’s second. 2-2. Hidegkuti hit the post. Kocsis hit the bat. Turek made save after save

And finally, with six minutes left, a cross slung into the box was nodded away only as far as Rahn on the edge of the box. He checked on to his left and sent a shot arrowing into the bottom corner. 3-2.

While the players were making themselves legends on the pitch, Herbert Zimmerman was doing likewise in the commentary box. His words as Rahn scores the winner are now part of German football folklore. “Tor! Tor! Tor! Tor! Tor fur Deutschland!” And then, unable to take it in: “Drei zu zwei fuhrt Deutschland! Halten Sie mich fur verruckt! Halten Sie mich fur ubergeschnappt!” – “3-2 to Germany. Call me mad! Call me crazy!” There was still time for Puskas to have a goal controversially ruled out for offside and for Czibor to be denied brilliantly by Turek. But Hungary could not find an equaliser. It was over. Or, as Zimmerman put it: “Aus! Aus! Aus! Aus! Das spiel ist aus!” West Germany were world champions.

The aftermath

The Miracle of Bern is a Sliding Doors moment. Budapest went into uproar, with demonstrations in the streets. In 1952 the Golden Squad had returned to a 400,000-strong party. In 1954 they waited for days in the town of Tata until the worst of the trouble had ended in the capital. There are those who feel that the seeds of the 1956 revolution were sown in those days after the final. As far as football was concerned,Hungary at first continued where they had left off in the semi-final, going another 18 matches unbeaten to take their record to one defeat in 49 games between June 1950 and November 1955. But the run petered out and Sebes was replaced early in 1956, his team and the coaching structures around it dismantled. The heights of the early 50s would never again be reached. Of the Miracle of Bern Tibor Nyilasi, who played up front for the national side in the late 70s and early 80s, told Jonathan Wilson in his book Beyond the Curtain: “It is as though Hungarian football is frozen at that moment, as though we have never quite moved on from then.”

While the Hungarians hung out in Tata, the German side had their own train troubles. The locomotive bringing Walter, Herberger and the Jules Rimet Trophy back to West Germany was stopped time and time again, not by leaves on the line or the wrong kind of snow, but by fans pouring out of their houses and on to the tracks in order to get a glimpse of the world champions and show their gratitude.

Not just the football team but the country moved from strength to strength. Academic studies have been written on the effect of the victory in 1954 on the collective German psyche. The writer Friedrich Christian Delius felt “a guilt-ridden, inhibited nation was suddenly reborn”. National pride, absent from the country after the horrors of 1933-45, could begin to return in some form. “Suddenly Germany was somebody again,” said Franz Beckenbauer. “For anybody who grew up in the misery of the post-war years, Bern was an extraordinary inspiration. The entire country regained its self-esteem.” West Germany had existed as an entity since 1949, but the historian Joachim Fest reckoned the day of the game marked the “true birth of the country”.

“Gerd Müller’s winner against Holland in 1974 is basically just a goal, as is Andreas Brehme’s penalty against Argentina in 1990,” writes Uli Hesse in Tor! “But Rahn’s left-footed shot on that rainy summer day in Switzerland is something else entirely.”

This piece is hugley indebted to Uli Hesse’s superlative Tor! The Story of German Football.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion