Follow us at @WorldSportCNN and like us on Facebook

Story highlights

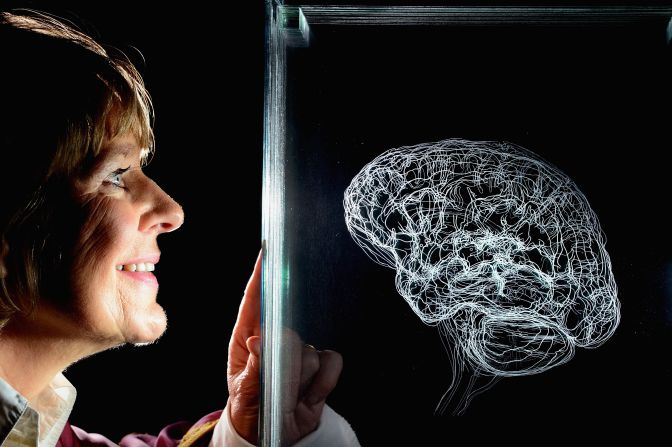

Professor Steve Peters has been hailed as a savior by a long list of sports stars

Psychiatrist's work in sport began in British cycling and now includes Liverpool FC

He warns that his approach, using "The Chimp Paradox," is no miracle cure in sport or life

Peters draws parallels with sport and working in a high-security unit earlier in his career

He helped resurrect Liverpool’s footballing fortunes, and he has been called up by England ahead of the World Cup in Brazil.

Britain’s most successful Olympian Chris Hoy calls him the “voice of reason,” snooker champion Ronnie O’Sullivan credits him with bringing him back from the brink of retirement, while footballer Craig Bellamy says he saved him from mental torture.

The list of sporting luminaries queuing up to wax lyrical about Professor Steve Peters paint the picture of a miracle worker, but the 61-year-old modestly downplays his role in helping shape British sport across a myriad of disciplines.

“It isn’t that I have a magic model,” he says. “People think it’s a cure but it’s not that. I just want to bring the best out of people.

“I can’t take someone off the street and make them a world champion in whatever sport they wanted. That’s not possible, as you need skill and ability with it.”

But Peters’ success in helping athletes is truly remarkable, being involved with numerous Olympic and world champions.

Not that he ever counted such things – it simply isn’t in his psyche.

Growing up in the northern English town of Middlesbrough, the son of a docker was the first in his family to go to university.

He taught maths before retraining to become a doctor, and jokes that he turned to psychiatry because “that had less on-call hours in those days.”

But it started his fascination with the human mind, which has not diminished.

However, it was never his overriding ambition to win medals – he got into sport by accident rather than design, working with a cyclist in 2001 “merely to help out a friend.”

“I just want to help people,” he explains. “My biggest satisfaction is getting a better quality of life, where you’ve seen that suffering and been able to remove that suffering, whether that’s in sport or their personal lives.”

His greatest and most prolonged success has come with British Cycling, where he was brought in by the forward-thinking Dave Brailsford – the man behind the success of Team Sky, home of Tour de France winners Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome.

Despite knowing little about football, Peters helped guide Liverpool to the brink of a first English league title in 24 years – and will again work with the club’s captain Steven Gerrard in the England World Cup campaign in Brazil.

He has helped five-time world champion O’Sullivan to fight his very public mental demons, and came to the aid of renowned “bad boy” Bellamy after the suicide of the former Liverpool and Manchester City striker’s mentor Gary Speed.

“Both Ronnie and Craig have been amazing pupils – both have worked really hard,” Peters says.

“Both started from a tough place. Sometimes people find it hard to understand that people have gifts but they can be put in a position that they’re not quite capable of understanding the emotion that goes with it, and they say or do things they regret.

“Both were determined to change and get the best out of themselves. It was hard work but enjoyable.”

So how exactly does Peters teach people how to control their brains? The basis of it is “The Chimp Model” – which he explains in his book as the different parts of the brain that battle for domination.

The emotional, irrational part is the chimp, which he challenges athletes to control, while seeking to remove “gremlins” and “goblins” – negative beliefs or behaviors that can inhibit performance.

“I use that model to access the mind as it’s much easier for people to think of something accessible,” Peters says.

“But you have to be adaptable to the individual, to understand their environment and get the best out of them. I often get asked for five tips to help people or something like that but it’s just not possible. A tip to one person won’t help another. Everybody is individual.”

Peters says athletes need to work on their mind as they would their technical skills or strength and conditioning, and he believes it requires just five or 10 minutes a day – which he does himself to keep his inner chimp at bay.

Despite all the successes, there are inevitable blips. Peters’ Midas touch, for example, seemed to evade him in recent weeks as O’Sullivan was unable to retain his world title while Liverpool slipped up in final stretch of the Premier League season.

“The driving force is that I like to see people succeed whatever it is they try to do, whether that’s medals or whatever,” he adds.

“I get asked if I fail but I can’t make people win. What I try to do is to take away the barriers that are governing them: ‘What are you trying to do, what’s stopping you?’

“It’s not for me to tell people. I just give suggestions.

“Ronnie O’Sullivan is a good example. People said it must have been a terrible day in that final. It wasn’t. Obviously Ronnie was disappointed as he wanted to win the title.

“But he was in a good place in the dressing room and was talking about someone playing out of his skin. He was like, ‘I’m doing what I can.’ For 20 years, he made three world championship finals and now he’s made the last three finals consecutively.”

Liverpool’s players and management alike have paid tribute to the Peters effect. He has generally worked with individuals, but likens tackling a football team as similar to his cycling experiences.

“Both Dave Brailsford and Brendan Rodgers are amazing managers, they know how to run teams. It makes my life easier as I’m just brought in to help. I’m just one of a number of people in a support team in both cases.”

It is all a far cry from his previous job working at a high-security psychiatric hospital for 12 years, dealing with people with a wide variety of personality disorders, and being helped to track down the Soham murderer Ian Huntley.

Are there any parallels between such clinical work and sport?

“In sport or the corporate world, in whatever, it’s more or less the same as you’re dealing with people and what’s going on in their head,” Peters says.

“If people are ill or people have forensic personalities, you still have to adapt in the same way to, ‘What’s my role in this?’

“Of course, it’s a very different remit deciding whether people need to be detained for public safety than riding a bike around a velodrome but it’s the same brain mechanics. It’s a little bit like running a car – it could be they have different engines but there’s a generic feel for those engines.”

If Peters can help England’s footballers to win the World Cup for the first time since 1966, he will indeed be dubbed a “sporting savior” – but he is wary of being seen as the only solution in such circumstances.

“It’s not just me, there are lots of people doing this,” said Peters, speaking more generally about his work, rather than specifically about the England team. “And people shouldn’t think mine is the only way.

“I might not work for some people, so my advice would be to find the model that works for you.”

Read: Will physicist change football?