|

By Cindi John

BBC News community affairs reporter

|

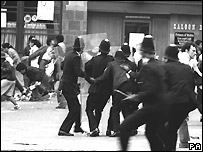

As the 25th anniversary of the Brixton riot approaches, BBC News examines the significance of the events of April 1981.

The rioting was sparked by the arrest of a black man

|

The rioting which began in Brixton, in the south London borough of Lambeth, in April 1981 shocked the nation.

For three days, rioters - predominately young, black men - fought police, attacked buildings and set fire to vehicles.

More than 300 people were injured and the damage caused came to an estimated value of £7.5m.

What was most shocking to many people was the unexpectedness of events. On the surface it seemed that black people were well-integrated into the fabric of UK society.

Many were second generation, born to parents who had come to Britain from the Caribbean in the late 1940s and 1950s to help "the motherland" with post-war rebuilding.

And there were high-profile success stories among Britain's black community. Trevor McDonald had been presenting the news on television since 1973, Lenny Henry was a popular comedian having won a TV talent show aged 17 in 1975 and Daley Thompson had won decathlon gold at the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

'Sus' law

But below the surface tensions had been building up and on 11 April 1981 they boiled over in Brixton, an area where 25% of residents were from an ethnic minority group.

The days of full employment were long gone and in Brixton around half of young black men had no job.

More than 100 officers were injured during the clashes

|

An amended Race Relations Act had become law in 1976 but police forces were granted an exemption from its conditions.

Many young black men believed officers discriminated against them, particularly by use of the 'Sus' law under which anybody could be stopped and searched if officers merely suspected they might be planning to carry out a crime.

In early April, Operation Swamp - an attempt to cut street crime in Brixton which used the Sus law to stop more than 1,000 people in six days - heightened tensions.

Unsubstantiated rumours of police brutality against a black man later led an angry crowd gathering to confront officers on the evening of 10 April for a few hours before the disturbances were contained.

But an arrest the following night sparked off the rioting in earnest.

But although its immediate causes were specific to Brixton, the rioting was perhaps a sign of the times.

The mixture of high unemployment, deprivation, racial tensions and poor relations with police were not unique to Brixton.

By the time Lord Scarman's report on the events in Brixton was published in November 1981, similar disturbances had taken place in a raft of other English cities, most notably Liverpool and Manchester.

Task force

In his report Lord Scarman said there was "no doubt racial disadvantage was a fact of current British life".

But he concluded that "institutional racism" did not exist in the Metropolitan force.

Eighteen years later Lord Macpherson would famously come to the opposite conclusion in his report following the killing of black teenager Stephen Lawrence.

Lord Scarman said the police were not "institutionally racist"

|

Lord Scarman recommended "racially prejudiced" behaviour should be made a specific offence under the Police Discipline Code with offenders liable to dismissal.

His report led to an end to the Sus law, the creation of the Police Complaints Authority and police/community consultative groups as well as new approaches to police recruitment and training.

But it would be another 20 years before the police came under the scope of the Race Relations Act with a duty to implement racially-sensitive policies.

And after the trouble spread to Toxteth in Liverpool in July the government announced the creation of an Inner City Task Force with a £90m budget to spend nationwide.

Political progress

As well as the political fallout on a national scale, events in Brixton added impetus to black people becoming politically active, first on a local and then on a national level.

In 1985 Bernie Grant became the first ethnic minority leader of a London council (Haringey) and two years later was one of the first four people from an ethnic minority to be elected to parliament (as MP for Tottenham) in modern times.

Increased black political participation followed the riots

|

The riots also helped crystallise plans by entrepreneur Val McCalla to start a newspaper aimed at the black British community.

The Voice, launched at the Notting Hill Carnival in 1982, quickly became a financial success largely due to job adverts by London boroughs which wanted to increase their diversity.

By the mid-1990s the Voice's influence in black British society was such that the then-Metropolitan police commissioner Sir Paul Condon accused it of sparking a race riot in Brixton over its reporting of the death of a young black man in police custody.

Deprived area

But the financial success of the Voice was not duplicated by many other black-run businesses.

In spite of initiatives such as the Inner City Task Force and subsequently City Action Teams and the New Deal, the "buppies" - young, upwardly mobile black people - of the 1980s were largely a passing phenomenon.

Major race riots returned to the UK during the summer of 2001

|

Since 1981 there has continued to be sporadic outbreaks of public disorder both in Brixton and other major cities, most memorably in the north of England when white and Asian youths clashed during the summer of 2001.

Eradicating the underlying social problems which are at the heart of many of the disturbances has swiftly climbed up the political agenda. The Labour government set up the Social Exclusion Unit to tackle issues such as poverty and unemployment after its election victory in 1997.

At the time of the 2001 census, nearly 40% of Lambeth residents were of ethnic minority origin. And although pockets of Brixton have gone upmarket, mainly due to an influx of city workers attracted by the area's central location, in 2004 the London borough of Lambeth was ranked the 23rd most deprived out of 354 English local authorities.

Reports since the Social Exclusion Unit was created have shown significant progress in some areas, such as reducing the number of children living in poverty and the number of people who sleep rough.

But other problems, such as the low academic achievement of boys of African Caribbean and Bangladeshi origin have proved harder to overcome.

And in spite of a government drive to bring more people into work, unemployment among ethnic minority communities is still twice the general rate.

~RS~q~RS~~RS~z~RS~08~RS~)