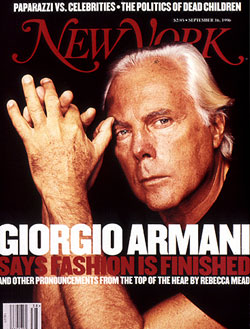

From the September 16, 1996 issue of New York Magazine.

Among the most exquisite of artworks in the city of Florence are the frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli that decorate the walls of the chapel in the Medici-Riccardi palazzo, a place of worship so tiny that no more than fifteen people are permitted to enter at any one time. Gozzoli’s purported subject matter is the Journey of the Magi: The three wise men, accompanied by scores of associates and retainers, process on horseback to pay homage to an unseen Jesus. But the actual subject of the frescoes is the glory of the Medici clan itself. Each figure on the walls has the face of this or that prince or nobleman, uncannily lifelike, gazing out at the onlooker. The chapel serves as a kind of fifteenth-century photograph album for the most influential family of the time, and even the Tuscan countryside—the dramatic, flowered hills through which the Magi ride—is depicted in glorious detail.

It was through those very hills outside Florence that, one Tuesday evening this July, another cavalcade of worthies ascended to pay their own kind of obeisance to contemporary power—not to a deity, but to a modern-day monarch of sorts: Giorgio Armani. During the few days prior, the men’s collections had been taking place in Milan, but Armani had determined to show in Florence rather than at his Milan palazzo. So that morning, the fashion caravan—that odd assortment of journalists and store buyers who travel from capital to capital, determining the rise and fall of the hipster pant or the patent-leather shoe—had climbed aboard trains or piled into rental cars and journeyed 200 miles south. Here they had witnessed not a mere catwalk show but a spectacular 90-minute-long performance and tribute to Armani created by the avant-garde director and choreographer Robert Wilson, who had created within the Stazione Leopolda, a vast, abandoned railway station, a series of surreal, beautiful tableaux, all peopled with models and dancers wearing Armani. There was a summer beach scene through which dancers dressed in the spring-summer 1997 collection wandered; a glamorous evening party in which the women wore gowns from Armani’s personal archive, which were in some cases as old as the bodies they hung from; a sculpture hall in which eight exquisitely muscled young men, barely dressed in swimwear, stood on podiums and affected the attitudes of sculptures, their hair whitened to connote marble, though it also bore a marked resemblance to Armani’s own stark-white coif. And after the show, a select group of spectators—Eric Clapton, Lee Radziwill, press, and buyers, as well as assorted Florentine bigwigs—were ushered into minibuses to ascend the dark hills above the Arno for a party in Armani’s honor, held on the candlelit terrace of a seventeenth-century villa.

They came bearing, if not incense and myrrh, then rich congratulations, even those who afterward admitted being bemused by the Wilson extravaganza and unable to focus on what was, after all, merchandise. (“I went to Florence to see the clothes, and I was a little disappointed that I didn’t see the clothes,” Kal Ruttenstein of Bloomingdale’s said later. “But I am sure it was beautiful: Everybody said it was beautiful, and fabulous-looking people said how beautiful it was, so I guess it was beautiful.”) Armani moved among his guests, speaking Italian to those who spoke Italian, French to those who didn’t, his manner one of quiet command. He wore a tight blue T-shirt and slim, tailored pants; he was, as usual, jacketless. With his deep tan and incongruously unlined face, his clear blue eyes, his impeccable limestone-white hair, his muscled arms and trim torso, Armani’s very person seemed to be fashioned from fabrics richer than those available to simpler, poorer folk.

For all the production values, though, it turned out to be a low-key evening, a party for people who are really too busy to party. The next morning, the fashion caravan was due to move on to Paris for that city’s men’s shows; the following week, it would shift en masse to New York, for the American collections. Long before dinner was served, the guests were comparing travel itineraries and declaring intentions to get to Florence’s minimal airport early enough to beat the crowds and, by implication, one another. Everyone was too busy wondering how to get back down to the city to enjoy being out of it. Armani himself slipped out before many of the guests had cleared, his social duties performed. Like those of the members of the fashion caravan, his thoughts were, presumably, already on what was to come next. The party was an essential display of power, but that power—the energy of a $1.7 billion business—takes more than late nights and glad-handing to sustain it.

This week, Giorgio Armani will be attending another series of parties, here in New York, as he arrives in town to promote two new stores, which open this Thursday on Madison Avenue. It’s Si Newhouse’s on Monday; the terrace of the new Giorgio Armani store at 65th Street on Wednesday; the downtown Armory for Emporio on Thursday.

The purpose of all the partying is to generate some heat around the name of Armani—who, at 62, is in the curious position of being routinely described as the premier fashion designer in the world, enjoying worldwide success rivaled only by that of Ralph Lauren, while at the same time being not, at the moment, particularly fashionable. In the past year, Armani has been repeatedly scornful of the clothes from houses like Prada and Gucci currently finding favor with tastemakers, castigating the designers for a thoughtless revival of the seventies and fifties, a willful ugliness, as contrasted with his stylistic consistency. He’s sounded, at times, a little cranky. “Maybe I went back to the thirties in my work, and they are turning back to the fifties,” he said in January. “The small difference is that in the thirties, the men were elegant; in the fifties, they weren’t at all.”

Armani’s irritation at his younger Italian rivals’ mining of fashion history (“I hope they will copy Armani from the eighties next, since we are in the seventies now,” he says, with sarcasm) is in part due to the fact that he is fashion history. He belongs to a tradition against which novelty is bound to react—particularly since the Armani aesthetic holds that novelty in fashion is not especially to be desired. Armani, says Richard Martin, the curator of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum, “is basically a design conservative. He is on the side of the argument which says that people don’t want this kind of rapid change in fashion. It’s a funny and strange alliance: The same attitude that leads people to say they are not going to spend money on clothes leads them to pay $3,000 for what they think of as a classic investment piece from Armani.”

And Armani has contributed to his own monumentalizing. As well as the Robert Wilson homage this summer, there was, several years ago, the film directed by Martin Scorsese, Made in Milan, a rather solemnly reverential, pre-Unzipped documentary about the man and his seams. He is of fashion, even at those times when he is not in it.

But for all the accolades, Armani shares the insecurity of anyone at the pinnacle of his achievement when that achievement is under constant evaluation in the marketplace: the isolation of success, and the necessity of maintaining it. “Nobody can tell me what to do—they are frightened to do it, because they think I am so sure of myself, so confident, and I have always got the right answer at the right time,” he says. “But I am just as full of insecurities as everyone else. My work has always demanded that I be very secure, that I have no doubts, that I make these decisions. In fact, Scorsese said to me, ‘When you arrive at the point of being the director, or the manager, everyone comes to you for comfort. But in fact, what you need is comfort from everyone else.’ “

Armani’s Milan office is dominated by a painting that bears its own passing resemblance to the Gozzoli frescoes in Florence, depicting a crowd of influential fashion folk from twentieth-century history. Chanel is there, as is Yves Saint Laurent. Valentino appears; so does Diana Vreeland. It hangs behind Armani’s desk, so that whoever sits opposite the designer also confronts his portrait, at the bottom left-hand corner of the canvas. A youthful-looking Armani—it was painted in 1978—is seated on the ground, his back turned toward the viewer, wearing only a pair of jeans shorts. He peers over his own bare shoulder, masking the lower half of his face with his upper arm. It’s a look that is both provocative and shy.

“I have chosen to make my work my life,” he says, speaking through a translator (Armani speaks no English, though he appears at times to understand it). “It is different perhaps with someone like Valentino. He has a very active social life, and he frequents a certain type of world, and I frankly don’t have time for that. I had to decide that I am going to enjoy my work. Every morning when I wake up and I jump out of bed like I did 30 years ago, I think: God, why don’t I just stay in bed and relax, have a leisurely breakfast? I could enjoy my wealth; I could rent a plane and go off for a week. But at the end of the day, I would be alone doing that, because I never lead that kind of life with people who are able to do that. And I don’t even have so strong a spirit of adventure.”

The real-life Armani often folds his arms across his chest in conversation, a gesture of reserve and defensiveness—but one that also allows him to flex his substantial biceps, demonstrating his reined-in power. Armani is, says designer Patrick Robinson, who worked for him in Milan, “very fortresslike. He shares the world that he wants with you.” Armani is notoriously disciplined, dedicated to a self-control and self-containedness that can come off as coolness. “I think Giorgio is an extremely warm, witty person,” says Gabriella Forte, his former right-hand woman, who now is president of Calvin Klein. “But he chooses not to put it on the table for anyone. It is not an assortment of hors d’oeuvre; it is not a buffet table. It is reserved for those who are close to him.” (It can be served up when necessary. When Armani stopped behind my chair at the Florentine party to say good evening, he gently ran his hands over my shoulders and stroked my hair—a surprising gesture with many layers, some of them certainly unconscious. It was partly, perhaps, some kind of paternalistic Mediterranean affection, and certainly a deliberate transgression of the boundary between subject and journalist. It felt like both a good-humored seduction and the mild pulling of rank: My being welcomed into the family entailed the expectation that I would not betray it.)

This tension between potency and restraint runs through his entire life, from the clothes he designs to the manner in which he lives, which seems to combine a monkish asceticism (he is, says his architect, Peter Marino, “Mr. Tidy Paws”) with an infinite luxury. He operates with what those who know him describe as an extraordinary focus, working long hours and exercising rigorously. A trainer works out with him every day, and he swims in the pool he had built in the basement of his Milan palazzo. It’s clear from his body that Armani takes great care to stay in shape, though he is blasé in a typically European manner about how he manages it: He eats less, and he has wine only with dinner, not with lunch. He saw himself on television about four years ago, he says, and realized that he had gotten fat. “So I began a strict diet for a week, and lost about six pounds.” And a week’s diet did it? “I don’t think it was that that changed me so much,” he replies. “I think it was a psychological thing. What affected me physically was that I wanted to be different.”

Director and choreographer Robert Wilson staged the Armani show at an old train station. “I went to Florence to see the clothes, and I was a little disappointed that I didn’t see the clothes,” said Kal Ruttenstein of Bloomingdale’s.

Yet along with the discipline there is the indulgence: Armani collects luxurious homes—he has a weekend house outside Milan and another in St. Tropez, as well as a compound on the remote island of Pantelleria. His headquarters will move several doors down the street this fall, to a grand eighteenth-century palace that is currently being restored. This arrangement, he hopes, will provide him with more privacy, though it is clear that the apartment is less a home than an extension of the office. “It doesn’t really feel like my house now; people wander in and out because they know I am there at a certain time,” he says. “So now finally I will have my house where I go in the evening and I close the door.” The expansiveness of his business has been built upon the narrowness of his life: One of his closest associates is his sister, Rosanna, who works for the company, and he has dinner with his 88-year-old mother at least twice a week.

In talking of his life and his priorities, Armani is, if not morbid exactly, then palpably conscious of his own mortality. “I like living with luxury, but I am not greedy for it,” he says. “I like it, but I am removed, because I know all this is temporary; at some-point, I have to leave these things because I am going to die. So I begin to prepare psychologically for this event. I could be very possessive, because I am a Cancer, so I am training my brain to leave earthly things. I am training myself to live the life still left with a different psychology.” He has, he says, reached a point where he is trying to focus on things other than the continuing expansion of his empire.

“I am enjoying the subtle things of life,” he says. “With this crazy race that I did to make myself known—to have some power, to have a position in the world, to have a name—maybe I often forgot some values that could seem less important but at the end give you a great deal of serenity.

“So I am learning to value even the simplest things in life: It could be a relationship with a person with a person; it could be a sentence; it could be a gesture, a way of dressing some woman; it could be the kindness of a look. Appreciating the things that I had forgotten.”

If Armani is looking to the end of his life, it might be because his success has been intricately tied up with death. It was eleven years ago that Sergio Galeotti, his former partner and the man he describes as his “intimate friend,” died at the age of 40, the cause variously described in press reports as heart failure after a long illness, and cancer. Galeotti was eleven years Armani’s junior and an architecture student; they had met in 1966. Armani, who had grown up in the provincial Northern Italian town of Piacenza, where his father was a shipping manager, had drifted into fashion, first becoming a buyer for a department store, then going to work as a designer for Nino Cerruti; in 1975, Galeotti urged Armani to go out on his own. Galeotti died just as the Giorgio Armani label was on the threshold of becoming an international phenomenon. In speaking of Galeotti, Armani becomes his most animated, vividly affectionate, urging his translator to do a good job.

“It was a relationship of great complicity,” he says. “A strong understanding. Without many words, we understood each other on everything: what we loved, what we didn’t love. And then there was a lot of courage on his part, which I was lacking, being more adult and therefore more cautious. He had a great deal of strength, and maybe even some form of irresponsibility. And I operated with a dose of realism, and maybe even a little genius that has been very useful to me in my life.” By the end of his life, Galeotti had tired of the business and talked of retiring. “We lived without even saying a word about his illness, without even letting it weigh,” Armani says. “He never saw me cry. He himself never said anything. In a whole year, he said once, ‘Giorgio, look how thin I have become’—that’s all.”

While talking of Galeotti, Armani notices that he is missing a ring he usually wears, one of two gold bands he wears with a triple-banded Russian wedding ring on the third finger of his left hand. When it is retrieved, he is asked what the rings signify.

He indicates the first gold band: “This band is one that Sergio had bought while by himself one day in the car. He stopped in a jewelry store and bought it for himself. It belonged to Sergio. But it was not given by me. He bought it for himself.” He moves to the next ring. “This is from somebody else”—he pauses—”who wanted to imitate Sergio.” He laughs. “And this”—the last ring—”is a present from a person very loved by me.” It’s as revelatory as Armani gets: the form of a confidence without the content.

“I don’t much like rings on a man,” he continues, “but this reassures me quite a lot. I am often moving my hands, like a good Italian. This allows me to move my hands.”

Armani’s representatives like to encourage a sense of the lone genius hovering over every aspect of the business, running it almost unaided; and though it is certainly an exaggeration, there is much truth to the image. After Galeotti died, Gabriella Forte became the formidable guardian of the Armani fortress, working as his head of international sales and handling his press. Her defection to Calvin Klein shocked the industry. About Forte Armani is polite, but still a little stung.

“In the end, I think, Gabriella wanted power,” he says. “I think she is doing a great job: Everyone is talking about Calvin; people are talking about her and what she has done for Calvin. What has been emotionally a little bit hard for me is that she has taken, or tried to take, quite a lot of my personnel to go and work for her at Calvin, which I think in America is quite normal but in Italy is not.” (Forte, who speaks feelingly of her personal indebtedness to Armani, says she can think of only two people who have followed her to Calvin Klein.) Armani asks for discretion on the subject of Forte, saying, “Gabriella has been very successful. I hope she will be happy with Calvin Klein. I have been shown to have survived without her.” Then he pauses, unable to resist a further comment. “May I add something? Maybe I am much more serene since she is not here. Very relaxed.”

Armani, though, is tart on the subject of Forte’s new boss, his new neighbor on Madison Avenue. “Calvin Klein, as [journalists] have said, not me, has moved from doing an Armani style to doing a Prada style,” he says. “He still has to find a more definite route. I think that it is a little more difficult for somebody who started off by designing underwear to move up to another product, as opposed to someone like me, who started doing an almost-couture line and then worked down to also doing underwear.”

Armani rolls his chair across the floor of a design room in his Milan headquarters, a girl in a plain muslin prototype for an evening dress before him, a clutch of serious-looking aides around him. Along one side of a long table, a phalanx of staff sits with sheafs of drawings and swatches of fabrics, their heads lowered, taking notes as Armani pieces together his designs.

He holds a fragment of sequined fabric up against the bosom of the girl wearing the muslin prototype, envisioning from this scrap a complete gown. He moves quickly, definitely, as another girl comes forward, wearing a long, sleeveless coat. “Molto ottanta,” Armani says, looking at her: “Very eighties.” He toys with the coat a little, pinning and tucking, trying to engineer timelessness.

Armani is widely considered the one designer since Chanel who can be said without exaggeration to have effected a lasting change in the way people dress: With his power suit of the last decade, Armani created a uniform that defined an era, albeit a uniform most people could only aspire to wear. And though the contours of his cuts may have changed slightly, Armani is basically creating the same relaxed, comfortable, luxurious clothes today as he always has done. “It is as if he is not fashion,” says the Metropolitan Museum’s Richard Martin, who wears only Armani. “When you see Dolce & Gabbana or Gucci, fashion as it is understood, Armani does transcend the moment.” Robert Wilson talks of Armani unequivocally as a fellow artist: “I think that if you are designing a dress, or if you are designing a chair, or you are designing a building, if you have to sing an aria, if you have to play a violin, Matisse making a drawing, it is all the same in one sense: It is line; it is shape; it is form; it is color.”

And yet Armani’s artistry is not the kind to be supported by grants from the NEA or friendly foundations. His only patron is the marketplace, which, in the realm of fashion, operates by whim at least as much as it does by any rational mechanism. Armani embodies an essential contradiction of fashion, which is the tension between the demand for novelty and the enduring appeal of a certain style. The fashion industry depends on obsolescence—those acid colors that were hot this spring are already burned out; the plum colors you buy this year will be past their sell-by date in March—while Armani’s clothes are predictably subtle, well-proportioned, and slow to date; they don’t cry out to be noticed.

“Fashion is finished; for me, the diktat is finished,” Armani says. “That is, ‘This is fashion, and you must dress this way.’ It’s finished. Fashion is what a woman makes: She puts on an Armani jacket, a skirt by Gigli. This is fashion. It’s old-fashioned when the magazines have this diktat. Old,” he adds in English, nodding for emphasis. “In the last ten years, too much has been done too fast, with everybody always looking out for something new; so every season there had to be something new, and everything was changing very quickly. So in the past ten years, everything has been done—so much has been done. And this is the negative side of fashion, in a sense, that has made it a bit ridiculous today, I think.”

In declaring fashion finished, Armani is, of course, being entirely fashionable: Even the New York Times weighed in recently with a front-page obituary. And if Armani’s vision of life after fashion still includes people wearing his jackets and Romeo Gigli’s skirts, then retailers needn’t be too worried. Fashion hardly looks finished, either, when you consider the activity taking place on upper Madison and Fifth Avenues this year. Versace, Prada, Valentino, and Ferragamo are also opening stores this year. Armani’s, like everyone else’s, are there not only to satisfy a demand for his clothes but to help create one afresh, to urge the ineffable whim of public desire to lean in his direction.

But it is true that while the fashion industry may, at least at the top end, be thriving, the notion of fashion itself is becoming more and more meaningless. Any discipline in fashion has long since evaporated; the idea of a single fashionable skirt length, or heel height, is incomprehensible. The definition of the fashionable has become so skimpy that it refers not to the mode of dress of everyday people—the clothes that have sufficiently caught the popular imagination to be worn in a widespread manner—but only to the styles that momentarily excite members of the fashion caravan.

If fashion is finished, if the struggle for preeminence in that sphere is bound to fail, then one option left for a fashion designer is to do precisely what Armani does: create clothes that aspire to a stylistic perfection, a classicism in the Greek sense. In the face of fashion’s demise, Armani continues to hold that there is, after all, such a thing as an ideal beauty. And that notion is one to strive toward, an idea as luxurious as Armani’s clothes themselves.

“People don’t need a lot,” he says. “They need much less—much, much less—than what we who make fashion think, or you who write about it.” The billionaire tailor is not being disingenuous. Armani maintains that people do need something, and that need is answered not by the temporality of fashion but by the eternal appeal of a harmony of form for which style is a wholly inadequate name.