When Julia Child spent Thanksgivings cooking at her home in Cambridge, Mass., she was never alone.

With her telephone number listed in the local directory, fans frequently dialed the famed chef on Thanksgiving to share their turkey troubles. Child never turned a fan away.

Amusing anecdotes such as this one are in plentiful supply in the new biography, “Dearie: The Remarkable Life of Julia Child.”

Author Bob Spitz pays tribute to Americas’ first culinary queen in this book, which will be in stores on Aug. 15, the year that would have marked Child’s 100th birthday. The 500-page tome also reveals some surprising insecurities that plagued the tall, eccentric chef with the loud, lilting voice in her early life.

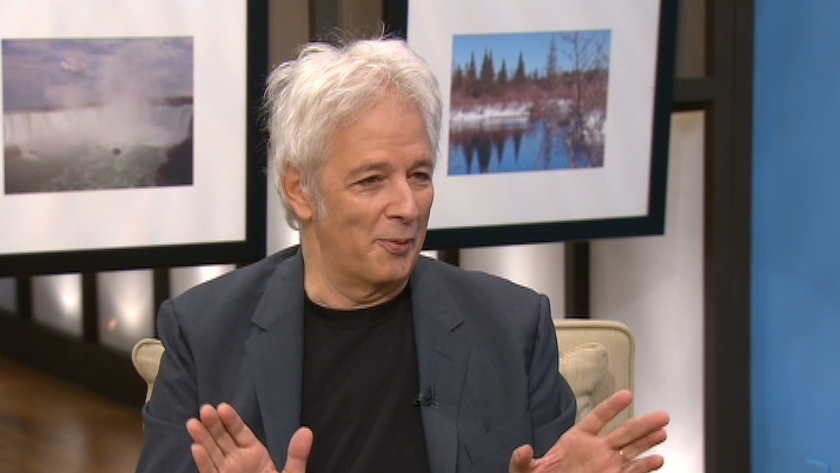

“I thought she was a remarkable woman…but she was a lost soul after college,” Spitz told CTV’s Canada AM on Tuesday.

“At the age of 40 she had never cooked. She couldn’t even boil water. At 50 she had never been on television. She remade her life at 50, so there’s hope for all of us,” said Spitz.

Known for her celebrity biographies, Spitz first met Child in Italy in 1992, while he was working on an assignment for a magazine.

During that visit, Spitz received a call from a friend at the Italian Trade Commission asking him if he would like “escort a woman” who would be travelling alone through Sicily.

“I told them I didn’t do that sort of thing,” Spitz said, with a grin.

When Spitz learned the woman’s identity, however, he jumped at the chance and spent several weeks touring Italy with the ground-breaking star of the 1960s’ cooking show, “The French Chef.”

“Julia poured her entire life out to me, and it was a life I thought was an adventure story,” said Spitz, who had Child’s blessing for this biography.

The book begins with Child’s first television appearance in 1962, then backtracks to her younger years she spent living with a wealthy, conservative father who believed that women were not equal to men.

Unlike many of her classmates, Child neither married nor had children after she completed her studies at Smith College in Northampton, Mass.

When the Second World War began in 1939, Child moved to Washington and worked as a typist in the State Department. She later became a clerk in the Office of Strategic Services, the first intelligence-gathering agency in the United State. That position took Child to China, Ceylon and India.

Those years abroad led some to believe that Child was a spy. Spitz squashes that theory, however, in his book.

“She knew the names of all the spies in Southeast Asia, but she herself was no spy,” he said.

During her postings in Asia, she met Paul Child, another civil servant. The couple fell in love and married in 1946.

When the Childs returned to America after the war, husband Paul was posted to Paris by the federal government. That fortuitous move introduced Julia Child to French cuisine and changed her life forever.

“Julia was relentless,” said Spitz.

Child woke at 5 a.m., started cooking at 6 a.m., and often worked until 2 a.m. perfecting her recipes.

Such dedication helped Child produce her 1961 book, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” The book was considered a groundbreaking achievement during that era and introduced millions of American housewives to French cooking.

“Julia cooked with shallots, leeks, and other ingredients things that American women could not find in their local supermarkets at the time,” said Spitz.

Thanks to Child’s book, Americans turned away from Jell-O molds, frozen dinners and converted rice and embraced the idea of cooking from scratch.

Child’s also encouraged fans to press food retailers to carry more exotic items in their stores, and thereby set a trend that would reshape the way North Americans would cook and eat in the decades to come.

“Julia was someone who wanted homemakers to have the ability to be stars in their own kitchens. That was feminism in its own way,” said Spitz.

“You never knew what she was going to say and she never liked things or people that were ordinary. But people embraced her wicked spirit,” he said.

“She taught us all how to eat and live,” said Spitz.