Giant screen looks for standards in digital projection

by Joe Kleiman

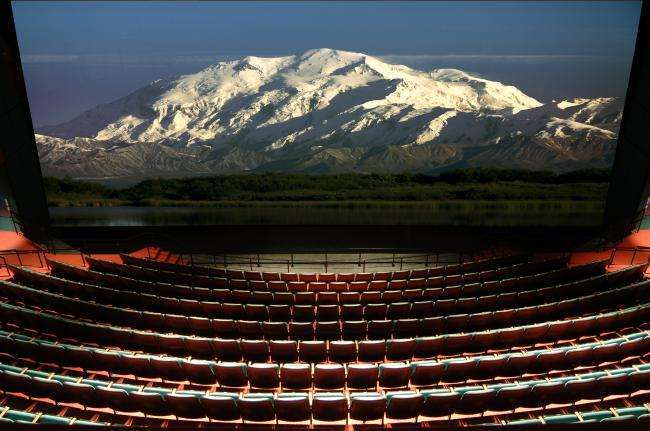

ABOVE PHOTO: IMAX digital projector. Photo courtesy of IMAX

Ben Stassen, founder of film production company nWave Pictures, has long been a pioneer in film-based attractions and giant screen cinema. He was one of the first to embrace film-based motion simulator attractions, with involvement in early breakthrough content such as “Devil’s Mine Ride” and the subsequent conversion of the simulation film library to digital and 3D formats. Always pushing the frontiers of distribution and production, Stassen entered the world of giant screen cinema, and his first 3D film in the format,1999’s “3D Mania,” was recognized by critics for its entertainment value and as proof of concept (Jim Bartoo of the Los Angeles Times: “a monumental breakthrough in 3D features that could easily have filmmakers pondering the idea of making the genre a part of filmmaking in the 21st century…” The nWave breakthroughs continued with the 2001 “Haunted Castle,” the first 40-minute giant screen 3D movie designed from the ground up solely as entertainment (and the first IMAX movie to receive a PG rating) and the 2008 “Fly Me To the Moon,” the first featurelength film conceived and designed for digital 3D from the very start.

“We’ve always been dedicated to the digital format,” affirmed Janine Baker, senior VP of distribution and development for nWave. We were at the annual conference of the Giant Screen Cinema Association (GSCA), which took place in September in Sacramento and San Jose. Baker was introducing nWave’s newest giant screen title there – Sammy’s Adventures: Escape from Paradise (also to be showcased at the IAAPA Attractions Expo this November in Orlando, in an abridged attraction version) as well as nWave’s upcoming documentary Last of the Great Apes.

But while nWave and other leading special venue producers have advocated digital projection for years, many giant screen exhibitors have stayed on the fence. Image quality is one issue: Current digital projection systems on the market do not match the high resolution or light output of traditional giant screen film systems. But changes in the business, such as the decline in the number of film prints struck each year, the desire to implement alternative and Hollywood content, and rising costs are prompting many to reconsider. Now, there’s an urgency to convert. I spoke with the director of one of New England’s most successful IMAX theaters, who summed it up, “Right now, ‘digital’ is the word on everyone’s mind. We’re here [at GSCA] because we know we need to do it and soon. But we need to figure out how we’re going to do it.”

As a giant screen projectionist, theater manager, and journalist covering the industry for the past 15 years, I too wanted to know the answer.

The hit-and-miss digital revolution in giant screen exhibition started as early as 1999 when IMAX purchased Digital Projection International (DPI) as a wholly owned subsidiary. IMAX/DPI went on to sign a partnership with DLP Cinema. After the development of a number of digital products, including the sale of DIGIMAX projectors, designed to project a 3-chip DLP image at 1080 resolution on a 50-foot wide conventional cinema screen, IMAX sold DPI in 2001.

IMAX would not introduce a giant screen projector to the digital market for another seven years, but some theaters chose not to wait. In 2006, as 2K digital projectors began rolling out to conventional cinemas, theaters such as Cinecitta in Nuremberg, Germany, began converting from IMAX film systems to digital projection using dual Christie 2K DLP projectors. Cinecitta’s sister company, Fantasia Film, began distributing digital 3D product, starting with “Haunted Castle,” to cinemas throughout Germany. By 2007, its customers included former IMAX theaters in Wuerzburg, Frankfurt (both operated by Fantasia Film), and Munich, all using the same dual Christie approach. The digital projection system launched by IMAX in 2008 uses similar equipment at its base combined with proprietary technology that enhances image and brightness.

At the GSCA conference, I sought to learn whether any issues had come up for exhibitors that had made the kind of film-to-digital transition described above, which would involve trading a 1.33:1 image at resolutions higher than 10K for a 1.9:1 image (the standard aspect ratio of digital cinema) at a resolution just slightly higher than 2K. To find out, I sat down with Tim Hazlehurst, VP of operations for the Marbles Kids Museum in Raleigh, North Carolina USA.

(As an aside, I consider Hazlehurst and his Chief Projectionist Tim Rectanus not only as colleagues, but selfless heroes of the industry. In former days as Director of Attractions at the National Infantry Museum in Columbus, Georgia USA, I received a call in 2009 that my IMAX print of “Star Trek” would not be available for a Friday opening at my theater due to a lack of shipping cases, I pulled together three of our own cases, rented a cargo van and made the 9-hour drive to Raleigh. Hazlehurst and Rectanus worked overnight unspooling the film from its platter and preparing it for shipment. To give you an idea of the work involved, a single second of IMAX film is about 5 1/2 feet long. And Star Trek is a 2-hour movie. “We wouldn’t have that problem anymore,” Hazlehurst noted, “Everything’s stored on hard drives now.”)

The Wells Fargo IMAX Theater at Marbles was an early institutional convert to IMAX digital projection, which Hazlehurst estimates cost the museum $560,000. “Our screen’s the same size – 52 ft high and 70 ft wide and only about 10 feet of the screen is not used with the digital image.” The IMAX digital projector uses a proprietary engine to bump up light output to 22 foot lamberts, 8 fL higher than the standard for digital cinema. And although the light output drops to 5.5 fL for 3D, mainly due to polarization, this is still twice as bright as the industry standard for digital.

Marbles has had no complaints from patrons regarding the new digital format, and finds one of the advantages of going digital is the ability to show a wider range of content. “We can show non-IMAX content on our system, but when we do we only use one of the two projectors.” That content has included National Geographic titles such as “Forces of Nature” and “Lewis & Clark: Great Journey West.” “As a children’s museum, we’ve done very well with our kids program that we get from distributor Big & Digital,” Hazelhurst told me. “Right now we’re showing “The Gruffalo.”

I asked Hazlehurst why IMAX was chosen over other options. “We decided on IMAX because of the brand. The brand has been very good to us.” The marketing power of the IMAX brand was also a governing factor for the Pacific Science Center in Seattle, where the Eames IMAX Theater was recently retrofitted with both digital and film-based IMAX systems interchangeable on rails. Other theaters, selecting different hardware, have dropped the IMAX brand and adopted the term “Giant Screen,” with a number prominently featuring their GSCA certification. COSI in Columbus, Ohio USA, converted its SimEx-Iwerks Extreme Screen Theater to a digital system designed and installed by Claco, a digital integrator for conventional cinema based in Salt Lake City, for $300,000. COSI then struck a licensing deal with SimEx-Iwerks for extended use of the Extreme Screen name. COSI marketing director Chris Hurtubise estimates the institution has saved 90% on maintenance costs with the new digital system.

The Putnam Museum in Davenport, Iowa USA went through two re-brandings. When first it replaced its IMAX system with twin Barco 4K DLP projectors from integrator D3D for $475,000, its theater became the “Putnam Giant Screen Theater.” That was eventually re-branded as the “National Geographic Giant Screen Theater,” joining National Geographic’s Museum Partnership Program, which was announced at the American Alliance of Museums conference in late 2011. I met with Mark Katz, president of distribution for National Geographic Cinema Ventures. “We launched the program in response to museums telling us they wanted a brand,” he told me. “For us the most important part is that they partner with us on content.” The program currently has nine partners.

National Geographic plans to distribute a minimum of 2 new digital 3D films per year and partner museums receive exclusivity on these films for their immediate market. Under the program, qualifying theaters may run Nat Geo content on any of their existing systems. “Museums not only gain access to the film library,” said Katz, “but they also gain unique access to the entire National Geographic organization, including our television, print, and exhibition divisions, and, most importantly, our members.”

Another company stepping up to meet the digital conversion needs of institutional cinemas is Giant Screen Films, which has been a key player in the giant screen industry since entering it in 2000 with a documentary on

basketball superstar Michael Jordan. Formation of its digital cinema arm, D3D, was “a classic case of ‘necessity is the mother of invention’,” said company president Don Kempf. “Several years ago, we worked out an arrangement with the exhibits company AEI whereby our large-format film “Mummies” became the official companion film of the King Tut exhibit. “Mummies” was an off-the-charts success at every Tut giant screen venue. With the exhibit scheduled to go to several museums that did not have giant screen venues, we worked with AEI to install digital 3D venues at these museums in time for their Tut runs. While not traditional giant screens, the attendance at these digital 3D theaters was incredibly strong.”

D3D has since installed a number of digital systems in giant screen theaters worldwide, including the Putnam, the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and Millennium Point in Birmingham, UK. In 2011 and 2012, D3D co-hosted the Moody Gardens Digital Symposium in Galveston, TX (in 2013, this event will be combined with GSCA’s spring cinema expo). Kempf told me, “We’re proud to have helped pioneer these symposia and facilitate many industry ‘firsts,’ including: first 4K giant screen demonstration, first 4K 3D giant screen film presentation, first back-to-back 3D technology showcase, first giant screen 1570 vs 4K shootouts (16:9 and 4:3), first high frame rate demonstration on a giant screen, first 3D audio demonstration in a giant screen theater, and first giant screen laser light engine demonstration.”

Another option is Global Immersion introduced its GSX system for flat giant screen theaters, placed into service on October 20, 2012 with the opening of the Peoria Riverfront Museum in Peoria, Illinois USA. According to Global Immersion’s CEO Martin Howe, “We use a twoprojector system that easily switches between aspect ratio – 16:9, 1.85:1, 1.89:1, 2:39:1, and what we call True 4:3. The system is capable of projecting in 3K x 4K resolution for a total of 12 million pixels.” In 3D (using technology from REALD), the GSX system can output 6-foot lamberts of light, a brighter 3D image than the Christie 2K-based IMAX digital projector (IMAX is expected to introduce a new digital projector using dual Barco 4K projectors at its core shortly). Global Immersion calls its GSX the “world’s highest performance and most versatile” digital giant screen projection system and believes the Peoria theater to be “the highest resolution digital Giant Screen theater in the world.” The theater is fully DCI (Hollywood studio’s digital cinema standards) and DIGSS compliant.

Within the industry, laser light is widely considered the holy grail of digital giant screen projection. IMAX, through its partial ownership of Laser Light Engines, LLP, licensing of Kodak laser projection patents, and partnership with Barco is forecasting a digital IMAX laser projector to be on the market possibly as early as 2013, promising richer color saturation, darker blacks, and the ability to brightly illuminate and fill a screen up to 120 feet wide. Other manufacturers, such as digital camera manufacturer RED, are entering the laser projection market. In addition to Barco’s continuing demonstrations of its laser projection technology, Christie showcased the Martin Scorsese 3D film “Hugo” to a packed house at a conference in Amsterdam this past August, using its prototype 4K DLP laser projector. D3D is also positioning itself to compete on laser projector turf.

According to Casey Stack, co-managing director of the Laser Illuminated Projector Association, the major hurdle in bringing laser projection systems to cinemas is government regulation. In the US, lasers are regulated by the FDA, with a number of states having additional local regulations. One of the big advantages to laser projection is the overall cost savings to the exhibitor. Whereas a xenon bulb usually has a life expectancy of 500 hours, lasers can operate up to five years at reduced operating and maintenance costs.

While the giant screen industry continues to pursue a number of options for digital projection, it also is working hard to establish standards. GSCA led in 2009 with the development of a giant screen specification and certification program (details can be found at www.giantscreencinema. com). Museum consultant John Jacobsen and his White Oak Institute (www.whiteoakinstitute. org) followed up with the Digital Immersive Giant Screen Specifications, funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation. DIGSS, now administered by GSCA, addresses giant screen domes as well as flat screens.

In 2005, Ben Stassen told my colleague Ray Zone (as documented in Zone’s book “3-D Filmmakers: Conversations with Creators of Stereoscopic Motion Pictures”), “. . . I am absolutely convinced that the Large Format industry will not survive unless it converts to digital projection technology within three to five years.” It’s no longer a question of when – it’s an issue of how. • • •

Joe Kleiman (www.themedreality.com) is a journalist, PR and marketing professional with a background in museums and special venue cinema.