1996

From left: "Three Friends", "The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well", "A Petal", "The Gingko Bed"

Although 1996 was a year that saw impressive debuts by some future giants of Korean cinema, perhaps the biggest debut of all was that of Korea's first international film festival. The launching of PIFF, the Pusan International Film Festival, was an ambitious and daring gamble that has proved to be one of Korean cinema's biggest success stories. Apart from its burgeoning importance to Asian cinema as a whole, the festival also served as the major catalyst in making Korea an active participant in the international film community, rather than just an observer.

The strong international reception of the festival also gave Korean cinema a platform on which to highlight some of its best films from the past and present. PIFF's first edition in 1996 featured debut works by Hong Sangsoo (The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well), Kim Ki-duk (Crocodile), and Yim Soon-rye (Three Friends). Hong Sangsoo has been described by many as Korea's most talented arthouse director; Kim Ki-duk's unique, tortured vision has fascinated international festival audiences, while Yim Soon-rye marks the first major female auteur to debut in contemporary Korea. PIFF was instrumental in launching these three directors onto the world film scene.

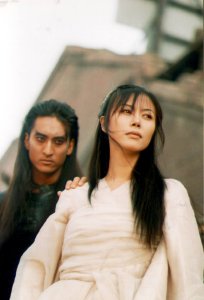

One last directorial debut of note was that of Kang Je-gyu with the fantasy romance The Gingko Bed. Although it proved a strong hit at the box-office and contributed to the emergence of actor Han Suk-kyu, it would be Kang's second film Shiri in 1999 that would really make waves in the industry.

Reviewed below: The Gingko Bed (Feb 17) -- Farewell My Darling (Mar 1) -- A Petal (Apr 5) -- The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well (May 4) -- Jungle Story (May 18) -- Festival (Jun 6) -- Their Last Love Affair (Jun 15).

| Korean Films | Seoul Admissions | Release Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Two Cops 2 | 636,047 | Apr 27 |

| 2 | The Gingko Bed | 452,580 | Feb 17 |

| 3 | Ghost Mama | 257,688* | Dec 21 |

| 4 | A Petal | 213,979 | Apr 5 |

| 5 | The Gate of Destiny | 200,570 | Oct 12 |

| 6 | Hoodlum Lessons | 176,757* | Dec 21 |

| 7 | The Adventures of Mrs. Park | 170,328 | Sep 21 |

| 8 | Born to Kill | 132,261 | Apr 19 |

| 9 | Corset | 114,777 | Jun 8 |

| 10 | Boss | 101,078 | Jul 6 |

| All Films | Seoul Admissions | Release Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Independence Day (US) | 923,223 | Jul 27 |

| 2 | The Rock (US) | 906,676 | Jul 13 |

| 3 | Two Cops 2 (Korea) | 636,047 | Apr 27 |

| 4 | Mission: Impossible (US) | 622,237 | Jun 15 |

| 5 | Jumanji (US) | 540,402 | Jan 20 |

| 6 | Eraser (US) | 516,721 | Jun 29 |

| 7 | Romeo + Juliet (US) | 491,435* | Dec 28 |

| 8 | The Gingko Bed (Korea) | 452,580 | Feb 17 |

| 9 | Twister (US) | 442,048 | Jul 13 |

| 10 | Daylight (US) | 434,099* | Dec 21 |

* Includes tickets sold in 1997.

Market share: Korean 23.1%, Imports 76.9% (nationwide)

Films released: Korean 65, Imported 382

Total attendance: 42.2m admissions

Number of screens: 511 (nationwide)

Exchange rate (1996): 851 won/US dollar

Average ticket price: 4,828 won (=US$5.67)

Exports to other countries: US$404,000

Average budget: 0.9bn won + 0.1bn p&a costs

Source: Korean Film Council (KOFIC).

Short Reviews

These are some reviews of the features released in 1996 that have generated the most discussion and interest among film critics and/or the general public. They are listed in the order of their release.

After telling French film critic Adrien Gombeaud that I was working on an essay about the significance of Kang Je-gyu's film Shiri -- a piece that thankfully was never published since I was far from fully happy with what I wrote -- I received an email from him wanting to make sure I didn't forget to underscore the success of Kang's debut film The Gingko Bed. Gombeaud made this extra effort with me because he wanted Shiri placed in its proper context. He didn't need to worry because I too wanted to challenge portrayals of Shiri as something that 'came out of nowhere.' Shiri wasn't out of its element, but instead a fish in water, a moment waiting to happen.

And Kang's work on The Gingko Bed was as much a part of Korean Cinema's productive milieu than any other. The year 1996, in some ways, represents a moment of greater things simmering underneath celluloid packaging, all the ingredients were beginning to mix for a vibrant Korean cinema to soon emerge. Kang demonstrated his potential with a very respectable gross of roughly 450,000 Seoul admissions, the second highest grossing Korean film that year (behind Two Cops 2), and one of only two Korean films to finish the year in the top ten.

And Kang's work on The Gingko Bed was as much a part of Korean Cinema's productive milieu than any other. The year 1996, in some ways, represents a moment of greater things simmering underneath celluloid packaging, all the ingredients were beginning to mix for a vibrant Korean cinema to soon emerge. Kang demonstrated his potential with a very respectable gross of roughly 450,000 Seoul admissions, the second highest grossing Korean film that year (behind Two Cops 2), and one of only two Korean films to finish the year in the top ten.

The Gingko Bed tells the tale of time-crossed lovers court musician Jung-mun (Han Suk-kyu -- Christmas In August, Shiri) and princess Mi-dan (Jin Hee-kyung -- Sweet Sixties) whose love for each other was severed by the possessive General Hwang (Shin Hyun-jun, as equally fully mascara-ed here as he is in Guns & Talks) over 1,000 years ago. Present day print-maker and art teacher Su-hyun (also played by Han Suk-kyu) is about to find out through strange dreams that he is the reincarnated soul of Jung-mun. These visionary dreams lead him to acquire a finely crafted and extremely heavy bed made from the wood of two gingko trees. The trees are alleged to be reincarnations of our two immortal lovers. General Hwang has resurfaced in the present day through stealing the heart of a rapist in order to track down and kill Su-hyun before Mi-dan can reach him. Mi-dan realizes human form temporarily through borrowing the body of a patient of Su-hyun's girlfriend, Dr. Ryu Sun-young (veteran actress Shim Hye-jin who would later star in yet another film about the past lives of a tree, Acacia). Unfortunately, Dr. Ryu pronounces this patient dead, so when Mi-dan returns his body, the patient's resurrection causes controversy for Dr. Ryu and her hospital.

The Gingko Bed is not my kinda film, too overly melodramatic too often, but I can see why it was so successful. The story maintains its internal logic for the most part while tapping into successful melodramatic tropes. This idea of reincarnated lovers will be used again and again in Korean Cinema in films such as Bungee Jumping of Their Own and The Classic. Further, stories of unattainable love, where some type of barrier limits the opportunities for a couple to consummate their love, e.g., Ditto, Il Mare, Failan, and, well, Shiri, turn up almost every year. I'm not claiming that The Gingko Bed "started" this trend. I haven't seen enough older Korean Films to make such a claim, and I assume the theme has been around for years. Still, The Gingko Bed's success may have made such stories more likely in the future. Still, The Gingko Bed may inhabit an interesting place within this genre since Dr. Ryu, along with being very self-actualized, eventually displays a interesting sympathy void of jealousy for her husband's time-crossing "affair." As for other aspects of the film, the suspense is held up well, buffered by the score when the action is lagging, although I personally didn't need the coda and wish it would have closed with the scene where all parties meet and Dr. Ryu attempts to clear her name. Considering the other films produced in 1996 that I've seen, the special effects utilized by Kang are decent, particularly when General Hwang steals the rapist's heart. Still, a scene of ancient decapitation had this child of Monty Python and The Holy Grail unintentionally laughing -- 'Tis a Flesh Wound!'.

Although Kang is not why I come to Korean Cinema, The Gingko Bed is my favorite of his three films. Taeguki may have proved to many that Shiri was no fluke, but The Gingko Bed shows the firmly rooted ground that Kang began upon prior to reaching the mountainous heights of the modern Korean blockbuster. (Adam Hartzell)

Farewell, My Darling begins and ends with images that strangely allude to future films by Park Chul-soo. We begin with a woman Push-Push-ing a baby into a dream of the patriarch, Mr. Park (Choi Seong). And it ends, (don't worry, this doesn't spoil it), with a snapshot reminiscent of Kazoku Cinema. As much as any director in South Korea, this continuity across films further underscores Park's intent to chronicle the changes that a Modernizing Korea has wrought and gifted.

And what more perfect a venue to explore those changes than the rituals surrounding that which never changes? Death. The family of Mr. Park returns to the village where the family was reared following Mr. Park's death. The cast of characters brings a circus to town of dreams met and deferred. Pal-bong (Kim Il-woo) returns from Seoul with the bling-bling of his new high-rolling status, fancy car, trophy wife, and child as accessory. Chan-sae (Park Jae-hwang) travels across the Pacific from America with his bible in hand and gospel music on tape. Chan-suk (Choo Kwi-jeong) finally makes the funeral only to open up old wounds that desperately need dressing. All the while Mr. Park's brother acts as the village elder who tries to wield an iron voice to force all to perform within his understanding of the proper rituals. His efforts are mostly in vain, however, for each party at this party mourns in their own way, from the calculated hysterics of the Aunties to the sincere gesture of Pa-yoo (Kim Bong-kyu) offering a bottle of pop (Yes, I'm from the Midwest) to deceased Mr. Park.

And what more perfect a venue to explore those changes than the rituals surrounding that which never changes? Death. The family of Mr. Park returns to the village where the family was reared following Mr. Park's death. The cast of characters brings a circus to town of dreams met and deferred. Pal-bong (Kim Il-woo) returns from Seoul with the bling-bling of his new high-rolling status, fancy car, trophy wife, and child as accessory. Chan-sae (Park Jae-hwang) travels across the Pacific from America with his bible in hand and gospel music on tape. Chan-suk (Choo Kwi-jeong) finally makes the funeral only to open up old wounds that desperately need dressing. All the while Mr. Park's brother acts as the village elder who tries to wield an iron voice to force all to perform within his understanding of the proper rituals. His efforts are mostly in vain, however, for each party at this party mourns in their own way, from the calculated hysterics of the Aunties to the sincere gesture of Pa-yoo (Kim Bong-kyu) offering a bottle of pop (Yes, I'm from the Midwest) to deceased Mr. Park.

Although I often mistakenly call this film Farewell My Concubine, the more appropriate films to compare with Farewell, My DARLING are Juzo Itami's The Funeral and Im Kwon-taek's Festival. Itami's film is a comedy that successfully transcended cultures in its display of Modern Japan's forgotten traditions. Several comedic moments also erupt throughout Park's film, such as Pal-bong, placing cashier's checks rather than won in the pot for Mr. Park's trip to the afterlife. Park's film, while showing what's been lost by South Korea's quick Modernization, also shows what traditions remain and what new ones have emerged. Interestingly enough, Im's Festival, about a matriach's passing, was made in the same year as Park's film. Im has said Festival served two purposes for him: to document Korean traditions at risk of extinction and to resolve his guilt around never performing hyodo (children's filial duty to their parents) for his mother. Park documents these same traditions, although not as meticulously as Im, such as feeding rice to the corpse and placing a marble between the corpse's lips. And including a director, Chan-woo, as one of the characters -- acted by Park Chul-soo himself -- we can not help but presume the character is a self-critique, similar to the role Ahn Sung-ki's character seems to play for Im in Festival. Interestingly, Chan-woo is asked to stand aside by his Uncle, allowing his younger brother to assume the role of the eldest son, since Chan-woo has been away from the village for so long, he is less familiar with the necessary rituals required.

Although the intrusion within the frame of disruptive sunlight in some scenes can be explained away as a desired documentary effect, the bad makeup, (or poor lighting of the actors and actresses that reveals the obvious makeup), is not something we can excuse. Such poor production reminds us how the high quality we've come to expect from Korean films had yet to take shape by 1996. Despite these flaws and the plethora of characters that are unnecessarily confusing at times, what Park's film shows most vividly is the community that emerges from moments that signify life's stages. As weddings are often more for the parents than the bride and groom, so are funerals often more for the living than the dead. This funeral is a time to eat, gossip, campaign, and transact business. And it is a time for traditions to be passed on through mimicry, such as the delightful scene where Pa-yoo repeats everything the men say, through repetition, such as the constant preparing and re-preparing of food, flipping of pa jun, pouring of soju, and through assimilation, such as the communal viewing of a Korean soap opera amongst the women, the snapping of gender-segregated photographs, and the very portrayal of all these events within this film. (Adam Hartzell)

The most earth-shaking event in Korean history after the end of the Korean War has to be the Gwangju Massacre in May 1980, when large crowds of students and citizens demonstrating for democracy clashed with special forces sent in by the government. The soldiers shot, stabbed and crippled large numbers of demonstrators (estimates of the dead range from an official government figure of 207 to a couple thousand), sending shock waves through the Korean populace. Ultimately this event more than any other would come to shape the future political development of Korea.

Director Jang Sun-woo was in jail at the time of the incident, arrested for organizing student rallies in Seoul. It was shortly after his release that he entered the film industry (he says, "I wanted to do something meaningful that wouldn't get me arrested"), and one of his longstanding goals was to make a film about the incident. Nonetheless, more than 15 years would pass before he found a producer with the desire and resources to bring these horrific and controversial events to the screen.

Director Jang Sun-woo was in jail at the time of the incident, arrested for organizing student rallies in Seoul. It was shortly after his release that he entered the film industry (he says, "I wanted to do something meaningful that wouldn't get me arrested"), and one of his longstanding goals was to make a film about the incident. Nonetheless, more than 15 years would pass before he found a producer with the desire and resources to bring these horrific and controversial events to the screen.

At the time that A Petal -- a big-budget (2.8 billion won) production by the standards of time -- opened production in late 1995, Korea had changed greatly but was still dealing with the aftershocks of the massacre. Now headed by its first civilian government, the country was witness to a public investigation into the events of 1980 that saw former presidents Chun Doo-hwan and Roh Tae-woo brought to trial (and eventually convicted, though for crimes unrelated to the massacre). With so much public attention focused on the incident, Jang saw less need to shoot a documentary-style presentation of the events themselves, and instead decided to depict the massacre's lingering effects in an indirect fashion. He has since referred to the film as a kind of ssitkkim-gut, a shamanist ritual meant to relieve a burdened soul (this is the same ritual Jang depicts at the start of his 1995 documentary on the history of Korean cinema, Cinema on the Road).

A Petal takes place somewhat after the massacre, focusing on a young girl who obviously suffers from severe psychological damage. The girl's dirt-streaked face and wild eyes (she is played brilliantly by actress Lee Jeong-hyun, who later went on to become a well-known techno pop star) seem not to register pain or normal emotions, and she can barely communicate. She attaches herself to a callous, disabled manual laborer (Moon Sung-keun), who sexually abuses her, partly in an effort to drive her away, but she refuses to go. At the same time we follow a group of four students who are searching for her -- she is their deceased friend's younger sister -- though they haven't any idea where to find her (among the actors playing the students are a young Choo Sang-mi and Sol Kyung-gu).

Jang's film uses flashbacks, haunting music, disjointed editing and even animated sequences to create a highly disturbing and initially confusing collection of scenes and impressions. We soon realize that this is not going to be a simple indictment of the government and the soldiers' actions -- as guilty as they may be, everyone in the film possesses the will and capacity for violence. Jang's disturbing use of rape to develop the film's themes has opened it up to attack from certain critics, although it should be said in Jang's defense that its role in the film is far more complex than the standard raped-woman-as-symbol-of-ravaged-nation allegory that so many films fall back on.

Despite the intensity of many scenes, what stands out most from A Petal is a black-and-white flashback at the film's end, which has to rank as one of the most powerful, heartbreaking moments contained in any Korean film. This is the ssitkkim-gut of which Jang spoke, a scene in which the nightmare is revisited and re-experienced in all its terror. Viewers should not expect any easy reconciliation or solutions after the massacre is re-played. Nonetheless the process may lead to recognition, and a chance of loosening one's grip slightly on the horrors of the past. (Darcy Paquet)

The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well

The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well

Made while Hong Sangsoo still held a day job at SBS, The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well fell into acclaim at international festivals, winning him dual Tigers, that is, the VPRO Tiger Award at Rotterdam and the Dragons and Tigers Award at Vancouver. It was not without success at home either, for Hong also doubled up on the Dragons by winning the Best Director at Korea's Blue Dragon awards. Although Hong would still keep a second job teaching film at Korean National University of Arts, the critical success of A Day a Pig Fell Into the Well did not prove fleeting, for Hong is still considered one of the primary auteurs of the new Korean Cinema that began to form after 1996.

Separated into four narratives, we slowly learn how each character is connected. Hyo-sub (Kim Eui-sung) is a struggling writer who isn't really struggling because of his writing, but because of his impulsive, angry tendencies. He is sexually involved with both Min-jae (Cho Eun-suk) and Po-kyong (Lee Eung-kyung) who each are followed in the final two narratives. Min-jae is a 24 year old woman making due with random jobs, both of which enact surveillance of her movement and voice. She pursues the affections of Hyo-sub even though he treats her like crap. Po-kyung is treated a little better by Hyo-sub because he claims he loves her. Po-kyong appears to walk, as if pulled along, in and out of Hyo-sub's embrace. It even appears that she might be leaving her husband for him, however, if this is the case, this effort is thwarted like so many efforts in Hong's films. Her husband Dong-woo (Park Jin-song) is followed in the second narrative and he heads to Chunjoo for business that is never consummated. Instead, he spends the night in a love motel with a prostitute trying to obtain something from her he could never have.

Separated into four narratives, we slowly learn how each character is connected. Hyo-sub (Kim Eui-sung) is a struggling writer who isn't really struggling because of his writing, but because of his impulsive, angry tendencies. He is sexually involved with both Min-jae (Cho Eun-suk) and Po-kyong (Lee Eung-kyung) who each are followed in the final two narratives. Min-jae is a 24 year old woman making due with random jobs, both of which enact surveillance of her movement and voice. She pursues the affections of Hyo-sub even though he treats her like crap. Po-kyung is treated a little better by Hyo-sub because he claims he loves her. Po-kyong appears to walk, as if pulled along, in and out of Hyo-sub's embrace. It even appears that she might be leaving her husband for him, however, if this is the case, this effort is thwarted like so many efforts in Hong's films. Her husband Dong-woo (Park Jin-song) is followed in the second narrative and he heads to Chunjoo for business that is never consummated. Instead, he spends the night in a love motel with a prostitute trying to obtain something from her he could never have.

Many of the themes consistent throughout Hong's later films find their origins here in The Day A Pig Fell In The Well. We follow separate narratives, although a greater number of them than we've followed before. Each main character is presented with serious flaws that inhibit their chances of finding fulfillment in their personal and professional lives. And moments that may initially seem irrelevant or represent bad editing choices amount to significant scenes with multiple viewings.

Yet what is most interesting about this film is what Hong chose to portray that he has since stayed away from in his later work. Dong-woo and Hyo-sub are probably the most pathetic men Hong has ever portrayed. The image of Dong-woo with his head down, arms and legs clamped, body shaking vigorously as he sits on the bed of the Love Motel is one of the most harrowing we've seen in Hong's films because this man appears to be losing it right before our eyes. Also, Hyo-sub and one of the side characters in this film are portrayed much more violently than any other character in any of Hong's films to follow. And it is the presence of these two differences, (plus, perhaps, the lesser production quality present here that we find throughout the Korean film industry until 1998), that give this film a feeling of hopelessness that I have not felt in any of the three films to follow this one. In the later films, although each main character traveled in a trajectory of poor choices, I always felt that there were positive trajectories available to them that could help them stray from their unhealthy patterns if they would only simply choose these alternate routes. Here, everyone seems to be trapped in their own personal wells with a rope not long enough to scale their way out, but definitely long enough to hang themselves. (Adam Hartzell)

According to Kim Hong-joon's harshest critic, Jungle Story is "The most boring rock movie ever made!" That unrelenting critic is director Kim himself. Kim is, of course, being somewhat facetious with that self-critique. What he really means is this is not the rock movie many might expect. As Akira Mizuta Lippit has noted, Jungle Story refuses to follow the basic rock film genre narrative trajectory: band forms, band rises to fame, band falls from grace, band learns moral lesson and/or rises again. Like later films such as Waikiki Brothers and Mr. Gam's Victory, we have a protagonist whose star doesn't shine as brightly as one expects in a usually star-studded genre. The boredom audiences might feel watching Jungle Story may be mainly from the dissonance certain genre expectations cause within viewers when not fulfilled by the director.

The story follows the character Yun Do-hyun, a young man fresh out of military service who decides to keep pursuing his rock star dreams in silent disagreement with his father's stern counter commands to pursue a direction that leads to a more reliably profitable profession. Yun instead takes a job selling guitars at a music store so he can practice while working and eventually slacks into the lead singer slot of a hard-rock-ish band. He is later discovered by a record executive through whom he also acquires a manager. The record he is contracted to make is pop-oriented, requiring aesthetic and ethical compromises fromYun. I'll stop with the plot trajectory here, since telling any more risks ruining some of the unique subtle shifting of this anti-rock, rock film.

The story follows the character Yun Do-hyun, a young man fresh out of military service who decides to keep pursuing his rock star dreams in silent disagreement with his father's stern counter commands to pursue a direction that leads to a more reliably profitable profession. Yun instead takes a job selling guitars at a music store so he can practice while working and eventually slacks into the lead singer slot of a hard-rock-ish band. He is later discovered by a record executive through whom he also acquires a manager. The record he is contracted to make is pop-oriented, requiring aesthetic and ethical compromises fromYun. I'll stop with the plot trajectory here, since telling any more risks ruining some of the unique subtle shifting of this anti-rock, rock film.

Yun Do-hyun is played by none other than Yun Do-hyun, a real-life 90's Korean rock star. However, he is not intended to be himself. Kim has utilized many 90's rock stars in this film, such as the members of Easy Rider, Anti-Social, and Monkeyhead. He also procured an actual rock basement venue, Rock World, as an onsite location within the film. And Yun's manager is played by Shin Ha-chul, whom Kim notes as one of the rare successful Korean rock stars before the 90's. In this film, Shin's character later becomes a concert promoter, underscoring his real-life charge to help bands acquire the recognition he feels they deserve. Kim is often asked if this film is of actors playing musicians or musicians playing actors, to which Kim responds, neither. These are "Musicians playing musicians."

Herein lies my main interest in Kim's film, the same aspect that, sadly, resulted in the weak turnout of paying customers, poor reviews from critics, and considerable humility upon the part of the director. Kim's main intent was to document the lives and methods of South Korea's 90's rock scene, not to follow mainstream film conventions. Perhaps Kim should have done a documentary instead, as he has suggested, but conveying such subculture specifics is fine for fictional features as well, it's just that doing such runs counter to mainstream cliches. And without those mainstream cliches, one can risk not obtaining mainstream success. So instead Kim has provided simple, smirk-inducing pleasures for those familiar with the underground scene, such as Yun's constant visits to the pharmacy to pick up a case of "Bacchus", a caffeine tonic that acts as a surrogate for the less accessible harder drugs for these harder rockers. Throwing back about 10 cans in one sitting apparently gives a considerable enough high that one would come back for more, as our pharmacist knows by eventually not even having to ask Yun what he wants when he enters her shop.

Kim attended Temple University in Philadelphia where he studied Anthropology. Such knowledge comes in handy when documenting a subculture. Particularly poignant is the explication of the Korean underground rock culture's own established ethical system. One of the ethical tenets Kim was exposed to was that which declares 'Thou Shalt Not Lip-Synch.' This tenet stands because it is believed each performance should be spontaneous and unique from the previous one. Kim has noted that this was the most frustrating part of making the film because of the subculture's resistance and, since this went against their ethics, they had little experience synching their performance to a soundtrack. (The drums were the most difficult to convey realistically in this process since even the most un-musically-skilled eye will notice mistakes in drum-synching.) Kim demonstrates this very frustration by including a scene in the Rock World venue where a video director runs up against this obstacle while filming. Such lip-synching of such raucous performances on such a grand scale places Jungle Story as an important film within Korean cinema's recent popular surge because the film broke sound ground from which later films could further advance. Although most commentators have focused on the advances in the visual production values of South Korean cinema, Jungle Story provides a turning point for sound production that scholars would benefit from investigating further.

Since this "boring" film failed at the box office and was panned by critics, one could say that the film was unsuccessful. Yet, to his credit, this reviewer, who has never found himself much enjoying the hard-rock genre, found himself appreciating a few of the songs appearing in the film, such as the last song played at Rock World's final day of business, a scene that eerily foreshadows the closing of the real-life Rock World after a long and antagonistic relationship with the local authorities. Yet even without an appreciation for hard rock, watching it within proper context rather than constrained within genre expectations and, to use film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum's term, "economic correctness," one finds that the film was indeed in sync with the people, the movement, and the time depicted within the film. And the narrative actually ended up being prophetic of the film's eventual reception. To have had Jungle Story perform otherwise would have been, according to this subculture, downright unethical. (Adam Hartzell)

Director Hinar Saleem's film Vodka Lemon (2003) has one of those unforgettable opening scenes. As quick as the crunching of the snow we hear upon the scene's arrival, an old man is dragged through the snowy streets of an Armenian village while still in his bed, a surreal scene that causes the viewer to stutter in their head wondering 'Huh?' We eventually discover this immobile man was being taken to a funeral to play his wind instrument. As he plays another man sings in Armenian. Brought back to the reality displayed in this fiction, I found myself reflecting on the fact that many foreign films released in the United States refuse to subtitle funeral songs. Funeral singing has been deemed something unnecessary to translate for United States viewers since, with the graves foregrounded, we get the picture. This makes Im Kwon-taek's Festival all the more unusual since not only are the funeral songs subtitled, but Korean viewers were offered titles that identified each step of the burial traditions, and English-viewers were provided with even more non-dialogue, ethnographic subtitles that documented the rationale behind each multi-theistic tradition.

Korean film scholar Han Ju Kwak states Festival is based on the writings of writer Yi Chong-jun. The film based on these stories follows a fictional author named Joon-sup (Ahn Sung-ki -- from The Housemaid to Arahan) who has returned to his home village due to the death of his mother. Upon leaving, his daughter Un-ji (Baek Jin-a) asks innocently "Grandma's dead again?", noting that there have been false alarms before. And it turns out Joon-sup's Mother fooled everyone again, because she is alive upon his arrival. (The actress playing Joon-sup's Mother is Han Eun-jin, who passed away in July 2003. She has been in close to 200 films, making me wonder, 'Should call her the Im Kwon-taek of Korean actresses or, since she outdoes Im twofold, if we should call Im the Han Eun-jin of Korean directors?' She debuted in 1939 in Mujeong and is most recognizable from Surrogate Mother.) However, Joon-sup's Mother does eventually pass away, bringing to the home family members, business associates, government officials, fellow villagers, and conflict. Much of the conflict involves impressions others have of Yong-sun (Oh Jeong-hae -- Sopyonje) and Hae-lim (Jeong Kyung-soon -- Taebaek Mountains, Segimal). Yong-sun is a niece whom Joon-sup's older brother had with a local prostitute. After Joon-sup's brother killed himself, Joon-sup's Mother insisted that the family take in Yong-sun. Yong-sun always felt like an outsider to the family, exacerbating this outsider status by stealing money from the family when she left for Seoul, and returning wearing garish makeup and clothes. Hae-lim is a magazine reporter who has followed Joon-sup's career and has come to the funeral to write an article. It is suggested that their relationship is more than just professional, and Hae-lim's presence discomforts Joon-sup's wife as much as the hole in the butt of her jeans delights the young children.

Korean film scholar Han Ju Kwak states Festival is based on the writings of writer Yi Chong-jun. The film based on these stories follows a fictional author named Joon-sup (Ahn Sung-ki -- from The Housemaid to Arahan) who has returned to his home village due to the death of his mother. Upon leaving, his daughter Un-ji (Baek Jin-a) asks innocently "Grandma's dead again?", noting that there have been false alarms before. And it turns out Joon-sup's Mother fooled everyone again, because she is alive upon his arrival. (The actress playing Joon-sup's Mother is Han Eun-jin, who passed away in July 2003. She has been in close to 200 films, making me wonder, 'Should call her the Im Kwon-taek of Korean actresses or, since she outdoes Im twofold, if we should call Im the Han Eun-jin of Korean directors?' She debuted in 1939 in Mujeong and is most recognizable from Surrogate Mother.) However, Joon-sup's Mother does eventually pass away, bringing to the home family members, business associates, government officials, fellow villagers, and conflict. Much of the conflict involves impressions others have of Yong-sun (Oh Jeong-hae -- Sopyonje) and Hae-lim (Jeong Kyung-soon -- Taebaek Mountains, Segimal). Yong-sun is a niece whom Joon-sup's older brother had with a local prostitute. After Joon-sup's brother killed himself, Joon-sup's Mother insisted that the family take in Yong-sun. Yong-sun always felt like an outsider to the family, exacerbating this outsider status by stealing money from the family when she left for Seoul, and returning wearing garish makeup and clothes. Hae-lim is a magazine reporter who has followed Joon-sup's career and has come to the funeral to write an article. It is suggested that their relationship is more than just professional, and Hae-lim's presence discomforts Joon-sup's wife as much as the hole in the butt of her jeans delights the young children.

Along with this straight, realist narrative, Im includes flashbacks of Joon-sup's Mother's gradual, developing dementia, along with fantasy sequences narrating Joon-sup's first children's book where, told from Un-ji's perspective, grandmother's dementia is described as her passing on her wisdom to her granddaughter. These fantasy sequences are presented as stage-like, with a background of fake scenery, to differentiate them from both the flashbacks and the regular narrative, which Han Ju Kwak notes is a "rare formal experiment in Im's filmography." These scenes serve several purposes. Besides helping Un-ji understand her grandmother's transformations and deal with her passing, they also serve as wish-fulfillment for Joon-sup since, unlike what is presented in the children's story, he did not take his mother into his home during her illness. Also, since Im himself has said that he regrets not performing hyodo, or filial duty to one's parents, for his mother, we can see this story within the story, as well as the entire work of Festival itself, as Im's attempts to resolve the guilt he himself carried.

Many films allow wonderful comparison prospects for Festival. Although Juzo Itami's The Funeral (1984) would be the one that would come to most world cinema viewers, in Korean cinema, Park Chul-soo's Farewell, My Darling is perhaps the most interesting comparison since it was released in the very same year and is a funeral film with which the director is equally, intimately entwined by the very fact that Park plays the character of a director returning home to his father's funeral. Yet, Im's eminent status as the present patriarch of Korean cinema, representing the national cinema on the world stage, causes me to reflect back and forth upon Festival's relation to the The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), the masterpiece of Iran's premiere director Abbas Kiarostami. Both films are, in a sense, self-critiques; however, I find myself preferring Kiarostami's because we do not end up with a white-washing, positive view of Kiarostami's director surrogate, but a complicated one. Whereas, Im's novelist surrogate ends up being the hero that patriarchally leads everyone back to their rightful place in the family, a source of major contradictions that Han Ju Kwak finds in the film in his chapter for the book Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema.

Festival is not one of Im's better films. All the films I've compared Festival with here in this review are much more accomplished works. The portrayal of Joon-sup's brother's widow Wedong-taek (Baek Seung-tae -- Chihwaseon, Silmido) comes off as choppy, as does much of the stage play entrances and line deliveries directed of some of the performers. Yong-sun's reconciliation with a family member who has nagged her throughout the film arises too implausibly. As a result, the film doesn't hold my heightened attention as does Park's. What Im has accomplished here is a studied detailing of the burial traditions. Interestingly, these pre-modern traditions, being a mix of Shamanism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and even Taoism, present a lie to the belief that Post-Modern collaging of cultural influences is anything new. Just as Han Ju Kwak notes that Joon-sup's mother's delayed deaths suggest "...the possibility that she is still alive, even after her actual death", Im's documentation presents how these traditions are still with us in hidden and visible forms, assimilating with and accommodating of the contemporary in order to survive along with us. (Adam Hartzell)

From their very first meeting, there is something desperate to the way that the journalist Kim Young-hee and the poet/professor Choi Young-min are pulled towards each other. Having read her glowing review of his poetry, he asks a colleage to invite her along for dinner and drinks. Perhaps he had lost his mind for her even before they met. He is married, with two children. She is single, but feeling the urge to settle down. They are wrong for each other in every way, but powerless to stop their mutual attraction, and very quickly they are in over their heads.

Adultery is one of the oldest topics in cinema, but Lee Myung-Se's Their Last Love Affair makes you feel like you are watching it for the first time. The relationship he portrays in this film is never romanticized, although the emotions it unleashes are nothing if not intense. The late Kang Soo-yeon gives a shimmering performance, reminding us of how much she contributed to Korean cinema through the sheer force of her presence. Kim Ghap-soo also gives one of the most effective and multi-layered performances of his career.

Adultery is one of the oldest topics in cinema, but Lee Myung-Se's Their Last Love Affair makes you feel like you are watching it for the first time. The relationship he portrays in this film is never romanticized, although the emotions it unleashes are nothing if not intense. The late Kang Soo-yeon gives a shimmering performance, reminding us of how much she contributed to Korean cinema through the sheer force of her presence. Kim Ghap-soo also gives one of the most effective and multi-layered performances of his career.

But Lee Myung-Se makes the film stand out in other ways, too. He is a master of mood through his precise control of color, movement and light, and the various spaces and locations that the characters move through play a big part in communicating their shifting emotional states. In the second half of the film, the couple relocates to an improvised home by the sea, and there's something both movingly down-to-earth and otherworldly about this temporary, contradictory space that makes it incredibly memorable.

But there are also very dark moments in this story, when the hopelessness of their situation causes the couple to lash out at each other. Young-min in particular is prone to fits of jealous violence, sometimes quite frightening. He is hateful in these moments, and the film doesn't ask us to understand or forgive him. Nonetheless there remains something quite sad and lingering about the doomed nature of this romance, so that by the end of the film we are feeling many different emotions at once.

From today's perspective, we can see that Their Last Love Affair marked a moment of transition for director Lee Myung-Se. There are some enigmatic, brief scenes in this film that don't connect in any way with the plot, but which now look like a foreshadowing of Lee's shift to crime and action-based storytelling in Nowhere to Hide. If the playful, innovative style he showed in the early part of his career could sometimes be described as fanciful, that word no longer applied to the films he would make from this point on. Lee's creativity would become more focused and sharp, and his worldview darker. It would result in some amazing films, and this one stands among the best of them. (Darcy Paquet)

Other films released in 1996

The Adventures of Mrs. Park (dir. Kim Tae-gyun), Armageddon (dir. Lee Hyun-se), Born to Kill (dir. Jang Hyun-su), Change (dir. Lee Jin-seok), Channel 69 (dir. Lee Jeong-guk), Corset (dir. Jung Byung-gak), Crocodile (dir. Kim Ki-duk), Ghost Mama (dir. Han Ji-seung), The Gate of Destiny (dir. Lee Kyung-young), Hoodlum Lessons (dir. Kim Sang-jin), Kill the Love (dir. Im Jong-jae), Love Story (dir. Bae Chang-ho), Piano Man (dir. Yoo Sang-wook), Seven Reasons Why Beer Is Better Than My Lover (dir. various), Three Friends (dir. Yim Soon-rye), Two Cops 2 (dir. Kang Woo-suk), Yuri (dir. Yang Yoon-ho).