I'm supposed to go flying over New Zealand's South Island with the director of the world's largest guidebook company, but I'm feeling haggard. Last night, Daniel Houghton and I made a little tour of Queenstown's bars: Winnies, the Buffalo Club, Zephyr, a few other places. There was a retractable roof, a lot of Red Bull and vodka, dancing and yelling, and a video of a man in a wingsuit tearing through narrow canyons. I left the last place—I think it was the Boiler Room—before Houghton did. “I don't feel anything yet,” he said, ordering another drink around 2:30 a.m.

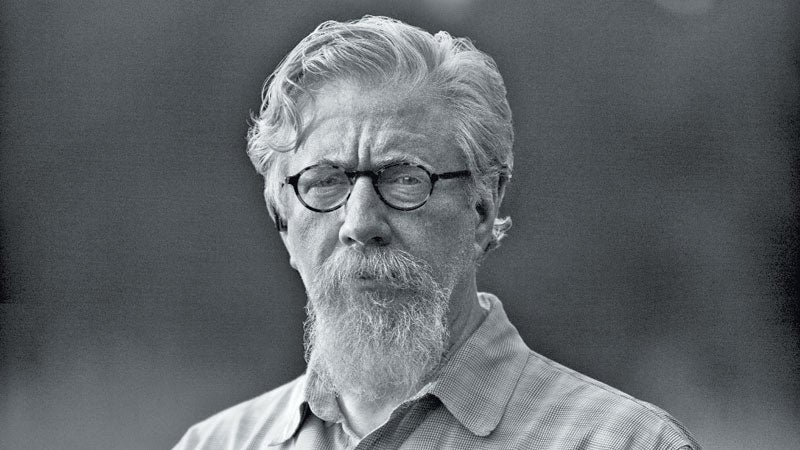

But when I knock on his hotel room door at 7:30, Houghton, now 25, is chipper. The space is fastidiously organized: bed made, camera gear in one neat pile, North Face and J.Crew clothes in another. Houghton, who is six foot four and 150 pounds, with a long neck and blue eyes, has rewired the sound system in the room to allow him to play M83 and the Lord of the Rings soundtrack from his iPhone. As he waves me in, he's on the line with his boss, billionaire Brad Kelley, the former tobacco magnate who bought Lonely Planet last year, when the storied company was in the midst of a financial nosedive. Houghton wishes Kelley a happy birthday, then we're off to ride what's billed as the steepest tree-to-tree zip-line on earth.

Houghton is in New Zealand to relax. He has been at Lonely Planet's helm for nine months, during which time he has invested heavily in a digital revamp and laid off nearly one-fifth of the workforce. “It's hard to turn a cruise ship around, so we had to get in a lifeboat,” he told me before we traveled to Queenstown. “A small one.” He has also come to see how the sausage gets made, accompanying a writer and a photographer on assignment for the company's glossy British magazine. The itinerary includes rafting the Class IV Shotover River, hiking the famed Routeburn Track, drinking Pinot at top wineries, off-roading in Houghton's dream truck (a Land Rover Defender, not available in the U.S.), watching the sunset over Lake Wakatipu, and searching for the moa, an enormous flightless bird capable of disemboweling a man with a claw swipe. Scientific consensus says that the moa probably went extinct about 400 years ago, but that doesn't dissuade Houghton. A typical guidebook-reporting trip, he tells me, “would be boring.”

A former wedding photographer, Houghton is documenting all this with his beloved GoPro for Lonely Planet's website. “We're paying people to survey the earth,” he's told me a few times, “and that's awesome. But readers should have the full experience writers are having.”

After a quick drive from the hotel and a short gondola ride, we're at Ziptrek EcoTours' mountainside course. Our launch point is a wooden platform built among some massive beech trees 1,650 feet up a hillside, where we clip into our harnesses and make our way to the pièce de résistance: line six, the steepest in the world. Houghton makes the leap. He flies upside down, holding his GoPro in one hand, his free arm relaxed behind his head and his legs crossed above him, swami style. He reaches 45 miles per hour, then flips back over smoothly as he meets the far-off platform in the trees, where a cute Ziptrek operator compliments his style. “This is gonna be a really cool video piece,” Houghton says with a smile.

Houghton grew up in a leafy Atlanta suburb. His parents worked for Delta Air Lines: Dan was a mechanic, Jean a flight attendant. The family flew for free, so Daniel visited 28 states by age 15. He liked anything fast—he started skiing at three—or high-tech. Dan thought he might have a pilot on his hands.

He was a middling student, but by tenth grade Houghton had discovered his real passion: photography. He enrolled in the photojournalism program at Western Kentucky University in Bowling Green and worked as a stringer for the Lexington Herald-Leader. At the Kentucky Derby, he twice captured the winning horse crossing the finish line, beating out older cameramen. He regularly skipped parties to be up and shooting at dawn. On breaks he flew standby to Argentina, France, and South Africa, where he photographed orphans with AIDS. Professors gushed about the maturity of his work, and Dan began to think that his son might someday shoot for National Geographic. Houghton interned at the Seattle Times and made the Sunday front page four times.

During his junior year, he interviewed at the Chicago Tribune. It went well, but then the Tribune began layoffs. Houghton graduated in 2010 with a major in photojournalism, a minor in entrepreneurship, and no dream gig. He married his college girlfriend, Susan, whom he'd met in the marching band. (He played Coldplay's “Postcards from Far Away” for her on piano before proposing.) Ultimately, Houghton landed at a small marketing agency in Bowling Green, shooting bank interiors.

“I remember thinking, Damn, that's lame,” says college friend Luke Sharrett, a photographer who has shot for The New York Times. After six months, Houghton quit the agency, filing for a business license the same day. He'd created a website for his work: Houghton Multimedia. Marketing jobs trickled in. He shot weddings on the side and made a little extra money as digital media adviser for WKU's student publications.

While Houghton was shooting a Bowling Green furniture company in May 2011, his cell phone rang. A local businessman who'd seen his website wanted to meet. Houghton showed up in jeans at a modest downtown office with no name on the door. He shook hands with three men and sat down. They watched some of Houghton's work on Vimeo—a video called “The Beauty of Digital Film,” about his grandfather's film projector; a contracted piece on Auburn University's new athletic arena—and asked questions: How did you make it? What did it cost? Did you have help? He was pretty much a one-man show, he told them. They said little about the nature of their business but asked him to come back next week for a meeting with their boss.

This time, Houghton showed up in nicer clothes. In the lobby, he was greeted by a big red-bearded man: Kelley. A self-made billionaire raised on a nearby farm who'd dropped out of WKU, Kelley, 57, had earned the majority of his money from tobacco and was now the fourth-largest private landowner in the United States, with property in Tennessee, Wyoming, Florida, New Mexico, Kentucky, Texas, Colorado, and Hawaii. Kelley did most of the talking, mainly about new media but also travel, conservation, and music. At the end of the meeting, he made Houghton an offer: keep doing what you're doing, but work for me. It was a handshake agreement, no contract. He never asked Houghton his age. For the next year, Houghton helped found and run NC2 Media, Kelley's fledgling company, with a staff that topped out at five. NC2 is short for in situ, a Latin phrase meaning “in position.” They launched OutwildTV, a website featuring sponsored expeditions—including a cowboy-journalist's 10,000-mile trip on horseback from Canada to Brazil, advertised as “one of the most daring journeys of the 21st century.” They also produced a gear blog.

Less than a year later, Kelley saw an opportunity. Lonely Planet, the Melbourne, Australia, guidebook company, seller of 120 million books, was struggling. In 2007, the BBC had bought Lonely Planet from its founders, Tony and Maureen Wheeler, for $210 million. Profits had since cratered due to the global recession, appreciation of the Australian dollar, and the struggling book industry.

Kelley offered $77 million for the company and closed the deal on April 1, 2013. There was no search for a new boss; he'd already tapped Houghton to captain the sinking ship. A few weeks before closing, the president of BBC Worldwide, Marcus Arthur, announced the impending purchase. Houghton, who was less than three years out of college, made the rounds at Lonely Planet's international offices. In London, before he introduced himself, someone projected an image of the biblical scene of Daniel in the lion's den on a screen.

“That pissed me off,” he recalls, “but I tried not to show it.”

Staffers were predictably bewildered. “I figured there had to be more to the story than 'reclusive billionaire hires 24-year-old with no known experience to run the joint,' ” a veteran Lonely Planet author e-mailed me. “But I think it's as silly and fucked-up as it sounds.”

Lonely Planet's largest office is still in Melbourne, but the de facto headquarters are now located in Franklin, Tennessee, a wealthy town of 65,000 described by its chamber of commerce as “fourteen miles and a hundred years from Nashville.” In March 2012, Kelley bought a $24 million business complex there and placed NC2 Media in a 12,000-square-foot studio of a former stove factory.

In October, two months before our New Zealand trip, I come for a visit. Houghton shows me his handsome corner office, a Restoration Hardware–inspired, compulsively organized aggregate of wood, leather, plasma screens, and family heirlooms. “We spent a lot of time putting this together,” he says. By “we” he means himself and his father—the elder Houghton did the drywall himself.

Today the CEO is wearing a denim jacket, skinny khakis, desert boots, Burberry glasses, a $4,200 Bell and Ross watch (“a gift to myself”), and enough hair gel to spike his Lincoln-esque frame to six foot five. He recently gave up on growing a beard. Houghton's desk is huge, made out of hundred-year-old French wood, and empty save for his computer and an odd adornment: a brass nozzle. “That's a fire-hose nozzle that Brad gave me,” he says. “It's sort of an inside joke between us. Doing this work is like trying to drink from a fire hose. Business is moving all day, every day, in different time zones.”

Some 400 e-mails met him when he arrived at 5:30 this morning—messages from Lonely Planet's other offices, in Melbourne, London, Beijing, Delhi, New York City, Los Angeles, and Oakland, California. His energy is high, boosted by a thermos of coffee. “You could argue that this is a bad time to get into the business,” he says. “But I think otherwise. The best time to get into an industry is when it's in flux.” Whether he learned this in college, heard Kelley proclaim it, or had an epiphany in the past 24 months—”since the early days,” he says, not meaning to sound funny—it comes across with surprising authority.

Houghton is a technophile. He owns two iPads (both sizes), an iPhone 5S, an HTC One (unlocked), a Samsung Galaxy Note, a Microsoft Surface tablet, and a 13-inch MacBook Pro. He shows me his iPhone. “Check out this awesome app,” he says of Fitbit. “It tells you how much you slept last night. I got five hours and forty-nine minutes! And I took 14,096 steps yesterday,” he continues. “I love apps. Our challenge is to design one that will change the way people travel.”

His confidence seems natural. Then again, it doesn't hurt to have a billionaire backer. From the start, Kelley didn't make Houghton adhere to a budget. His guiding principle, according to Houghton: As much as necessary, as little as possible. “There are million-dollar decisions I can make without asking him,” Houghton says of Kelley. “And $10,000 decisions I need to make with him.”

Though he consulted with Kelley, the layoffs were ultimately Houghton's call. Last July, a few months after NC2 took over the company, 75 of Lonely Planet's 383 full-time employees were made redundant. “I walked up in front of a microphone in Melbourne, where most of the redundancies occurred,” he says, “and told them, 'Today is going to be a really tough day.' ” The Internet rushed to write Lonely Planet's obituary; the hashtag #lpmemories took off on Twitter.

Among those laid off was longtime editor Suki Gear, along with her five-person publishing team in Oakland. “We all knew there was going to be an announcement,” she recalls. A travel site called Skift had broken the news before Houghton. “We cried and we laughed,” she says, “like in the movies.”

Many of those laid off were, like Gear, book editors. Houghton's not a print purist. “I woke up the other night thinking about digital publishing,” he says, pacing his office. “I know we want to do a digital magazine. When I see opportunities, my instinct is to jump on them. Ripping a book's pages out and putting it in an e-book: We can do that, and it's great. But that's not a paradigm shift.” He pauses. “We'll keep publishing books. We can make the crap out of books. And books are going to remain relevant to people who like to hold things.”

I ask what the market research says about all that. “I didn't really look at it,” he says, lowering his voice conspiratorially. “I don't really go with market research. I kinda go with my gut.”

Lonely Planet's head of mobile products, Matthew McCroskey, 26, knocks. He resembles a young Steve Jobs: the glasses, the hair, the beard, the pallor. McCroskey was running his own mobile-consulting firm in Nashville when Houghton saw his website and hired him. They discuss a postcard app, which Houghton calls low-hanging fruit. Using reader-submitted photos, the app will offer a stream of postcard-style travel pictures for aspirational viewing on a smart device. Houghton shows me a few images on his iPad and suggests some design elements to McCroskey. “

We can get this knocked out in a week,” he says. “Travel porn in time for Christmas!”

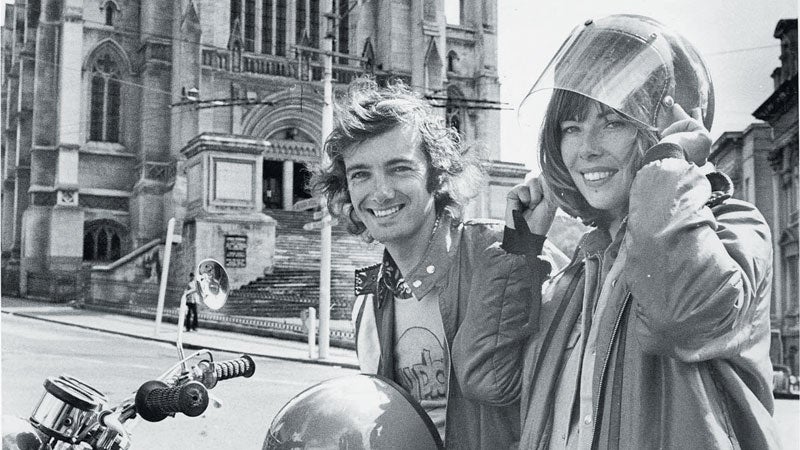

This is a far cry from the rough-and-tumble beginnings of Lonely Planet. In the early seventies, a newlywed couple from England and Ireland took off on an adventure and wrote a how-to book about it for their friends, called Across Asia on the Cheap. Along with standard travel advice, Tony and Maureen Wheeler offered political and religious commentary, tips on dope (“Have your last drag before you get to the Iranian border”), and financial advice during emergencies (“Several places have a good price for blood”). It became the first Lonely Planet text in 1973. The company name came from Tony's mishearing of a lyric in Joe Cocker's “Space Captain”: Once I was traveling across the sky/This lovely planet caught my eye. Lonely Planet found authors in bars.

Before long, the company was dominating the guidebook market in the UK, Australia, and much of the rest of the world by, as former CEO Judy Slatyer says, “telling it like it is, without fear or favor.” By 1999, it had sold 30 million guidebooks. As Lonely Planet pursued wealthier readers, it inevitably became more mainstream and flush. Authors enjoyed profit sharing and weeklong bacchanals in Australia on the company dime. These events culminated in a Christmas ball at the Melbourne office, to which authors were chauffeured in limousines. “The events were renowned for their scandals, brawls, and general tomfoolery,” says longtime author and former publisher Ryan Ver Berkmoes. “In the morning, you'd tamp down your hangover by gleefully figuring out who'd slept with whom the night before. Utterly ridiculous, but very fun to live through.”

Things changed after 9/11, as fewer people left home and the travel industry took a major hit. The growth of online publishing also hurt. Lonely Planet's profits suffered from 2001 to 2007. Then came the recession. Between 2007 and 2012, combined sales from the top five travel publishers fell from $125 million to $78 million. Online resources like TripAdvisor and Wikitravel gained ground as Lonely Planet, Rough Guides, Frommer's, and others struggled to make a digital footprint. Lonely Planet soldiered on, creating an online forum for travelers called Thorn Tree and pursuing opportunities in television and burgeoning markets in Asia. By 2008, however, the parties were over and the books had lost even more of their signature spunk. “They were editing like every verb might have a bogeyman underneath,” says Ver Berkmoes. “You couldn't say a town was bad.”

“We should have moved much more aggressively into creating a digital space where travelers could engage, interact, write their own guides,” says Slatyer, Lonely Planet's CEO at the time of the BBC purchase.

After the BBC bought the company from the Wheelers, it appeared to embrace a strategy of overspending and underimagining. “The BBC's culture is inherently conservative,” says Vivek Wagle, Lonely Planet's director of editorial for digital platforms from 2004 to 2011. “It's tough to innovate.” Tony Wheeler, watching his old company from the sideline, grew concerned. “If I have a single look-how-it-went-wrong pointer,” he says, “it's TV. Lonely Planet made more television in the five years before the BBC's purchase than in the five years after.”

Lonely Planet wasn't for sale when Kelley first approached the BBC, in April 2012. But the broadcasting corporation quickly made it clear that it would prefer to be unburdened of its investment. So why did Kelley buy? He didn't respond at first when I posed the question to him through Houghton—he famously avoids press attention—but those who know him insist that he doesn't make vanity purchases. Kelley, who says he has never smoked, founded tobacco company Commonwealth Brands in 1991 and sold it a decade later for $1 billion. He also owns Calumet Farm, a producer of thoroughbred horses, and a northern Colorado business park called the Center for Innovation and Technology.

Houghton did much of the due diligence in preparation for the Lonely Planet purchase. By December 2012, he felt that he was going to have a major role in the takeover. A month later, they were sitting in the Franklin office. Kelley said, “There's something important I need to ask you. Do you need to be liked?” Houghton replied, “Well, I want to be liked.” ”That's not what I asked,” Kelley said. “I don't need to be liked,” Houghton said. “Good,” Kelley said. “Needing to be liked is a problem. As long as you understand that, this will be fun.” Recalling that conversation now, Houghton says, “I became the director, 24 years old, and I go fire a bunch of people. They think I'm an idiot. It didn't make me popular. Brad prepared me for that. The guy is a fucking genius.”

After repeated requests, Kelley finally consented to a written interview about Houghton's hire. Houghton mediated it, because Kelley doesn't use e-mail. It was one of the land baron's only interviews in the past decade and the only time he has spoken publicly about Lonely Planet. His answers totaled 118 words. He wrote, “Daniel has created his own opportunity. While we share some characteristics, such as drive and an ability to adapt, his superior organizational skills along with personal and communication skills have made him invaluable to the business.” About that first meeting with Houghton, in Bowling Green, Kelley wrote: “Kismet. Simply put, a fortunate event.”

Like most everyone else, Dan Houghton still wonders why exactly his son has been given such power. Kelley provided a clue when they met one day at NC2 headquarters. “Did Daniel tell you what I called him the other day?” Kelley asked, according to the elder Houghton. The Delta mechanic shook his head. “Well, I told him he's like a Mennonite. You just don't find that many young people who are so focused on becoming something.”

Tony Wheeler used to have a routine in which he'd hold up his laptop, GPS, and cell phone and say, “Here's the guidebook of the future.” Then he'd hold up a PalmPilot and continue, “All we have to do is squeeze it into this.” The technology to do just that exists, of course, but neither Lonely Planet nor any of its competitors has got a handle on the squeezing yet. No one seems to know what, exactly, the guidebook of the future should look like. Google bought the U.S. company Frommer's in 2012 for a reported $23 million, announced plans to discontinue the print edition—then sold the company back to founder Arthur Frommer without explanation for an undisclosed amount. Since then, the publisher's biggest move has been releasing 30 significantly smaller guides this past winter. London-based Rough Guides is digitizing its entire travel catalog and acquiring author rights “for a fully flexible future,” according to its publisher, Jo Kirby. Let's Go and Fodor's are doing much the same. But these are minor adaptations. “

I travel as often with digital guidebooks as print ones these days,” says Wheeler, “but they're far from perfect. It's often way faster to find things in a book than on an iPad. And the batteries don't go flat.” But is Houghton the guy to reinvent Lonely Planet? “If you're going to do something different,” Wheeler says, “you better do it with somebody different. Certainly you don't want someone old and set in his ways—like me—at the controls. Is he the right 25-year-old? Jury is out on that one. He seems a nice guy.”

Of course, there's a saying about nice guys. Some observers are skeptical that Houghton has the skills necessary to run a multinational business. One former editor, a victim of the layoffs who asked not to be named because he still freelances for the company, says, “Houghton's age isn't an issue, but his lack of experience is. Daniel has never run a company of any size before and has only a few years' experience of even being in the workforce. Kelley himself has never run any sort of content business or global company before. There has been no articulation of future strategy other than vague, empty phrases such as 'digital first.' ”

Suki Gear, the former head of the Oakland office, worries that Lonely Planet will become like TripAdvisor—crowdsourced, free, often unreliable. “I hope they keep the authors,” she says. “They're a goldmine. If they go with user-generated content, it's all over.”

Still others think that the company will only succeed if it ditches books entirely. Last year, at the All Things Digital conference in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, Myspace cofounder Chris DeWolfe approached Houghton and asked, “Are you the young guy running Lonely Planet?” According to Houghton, DeWolfe said that the company wouldn't succeed unless it moved to Silicon Valley.

“I have great respect for him,” Houghton says of DeWolfe, “but when he said that, I got even more amped about succeeding. Everyone is entitled to their opinion. But what really frustrates me is when they say things that aren't true. People continue to claim that we're getting out of the content business. I'm like, What? That's not right at all.”

One day in his office, Houghton reveals a bit more about his content strategy, drawing a pyramid bisected by four horizontal lines on a piece of paper. In the top section he writes authors. “There aren't many of them,” he says, “but they're really important.” The next section says residents. It's followed by somewhat vague and overlapping categories: freelance, super fans, and online community. Some of these “content producers” will be paid. But most will not.

“It's not perfect,” he admits. “But the system of sending one author to write about a vast place is antiquated. And there's a lot more information we need to supply more quickly to remain relevant. We want the latest content, in real time.”

That means apps. Lonely Planet's apps have been downloaded 11 million times, about the same number as Yelp. (Houghton wouldn't comment on the company's profits since he took over, but he says that digital now accounts for 30 percent of Lonely Planet's revenue.) In November, Lonely Planet purchased TouristEye, an app for planning trips and discovering new things to do while traveling. It was a six-figure deal, but not just for a cool app. Houghton was most excited about recruiting the talent behind it to help him answer what he and his team consider to be a billion-dollar riddle.

“Can you tell a traveler what he should be doing right now?” asks McCroskey. “Based on time of day and where he is and the weather and a million other factors? A lot of people have made headway in that space but hit a wall because they didn't have enough information. Well, we have tons of information—all of Lonely Planet's historic content. And we're building really great technology to analyze that content and understand all the ways you can put it together.”

McCroskey then offers a concrete example of how the system will work: “You're in Rome, standing by the Colosseum. It's 3 P.M. on a Thursday in summer. You open your phone, and it says, 'Hey, glad you enjoyed the Colosseum, which was on the itinerary we helped you make. We know you love coffee. Time for a cappuccino! The best cappuccino place in Rome is two blocks away. Here are walking instructions. And while you're walking, you should know: Don't order a cappuccino in the afternoon in Italy; they only drink them for breakfast, and they're going to think you're a stupid American. So you should get a macchiato. And this is how you ask for it.'”

“If I were you,” continues McCroskey, “I'd assume we don't know how to do that. It's not here now, it's not trivial to build, and I'm not going to give a release date. But we've got most of the people who can deliver that kind of experience. And Daniel is finding more.”

One morning in Franklin, as I walk into the Lonely Planet offices, Houghton is seeing out a serious-looking young man named Joe Bochenek. When Houghton reappears, he says, “Dude, he's a particle physicist. He helped discover the God particle! And he just explained to me why time travel won't work.” The man—who did indeed contribute to the discovery of the Higgs boson—has just accepted an offer to be a Lonely Planet data scientist. His role is to analyze the company's vast stores of travel information, helping McCroskey's team categorize customers. Lonely Planet is no longer hiring in bars.

Personally, I'm not sure I'd hand over a company valued six years ago at a quarter of a billion dollars to a 25-year-old. But if I did, he'd be a lot like Houghton: impossibly driven, optimistic, charismatic, with a tech fetish and a welcome dose of humility. “Zuck,” Houghton tells me, referring to Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, “has a card that says 'I'm CEO, Bitch.' I'm the opposite of that.” Houghton prefers not to use titles at all. During the week we spend in New Zealand, he repeatedly takes pains to avoid discussing his job. If pressed, he just says, “I work for Lonely Planet.”

Houghton also displays very little fear. While rafting the Class IV Shotover, he paddles with the zeal of a GoPro-clad Ahab. In Queenstown, the adrenaline capital of the world, he wants to try out a frightening thing called a canopy swing—basically a free fall from a cliff while attached to a rope that swings outward instead of plummeting straight down. Against my deep reservations, he convinces me to join him. Fortunately, it's closed when we arrive.

Instead, we head to Fergburger—a hyped-up burger joint in Queenstown whose fame is partly due to Lonely Planet's recommendation—and then back to our hotel, where we sit on the patio and drink: water for me, wine for him. Houghton makes a call, hoping to lock down new office space in London. He laughs a lot on the phone. “I've got a great team,” he says, sincerely, after hanging up.

I can't help but nod my head when, moments later, he utters one of his motivational standbys, apropos of nothing in particular: “Travel is a force for good.”

We try that mantra out a few days later on the Routeburn Track, one of the most famous walks in the world. The three-day hike is fairly busy for a remote place, with people trudging along happily in small groups. Ours consists of about 15 people, including a TV producer from New York, a lawyer from Colorado, and a biology professor from Massachusetts. One day we eat lunch in a hut with a young couple from Belgium, who've mentioned their love of the company's books. When Houghton gets up to refill his coffee, I can't resist telling them his secret.

“He's a writer?” asks the man.

“No,” I say. “He's the CEO.” The woman turns pink and adjusts her hair. When Houghton returns, the man eagerly pitches his brother as a candidate for a guidebook-writing job. Houghton, used to this, patiently tells the man to have his brother e-mail someone at the company. “They read every e-mail,” he says. “I promise.”

The quietest member of our group is a college kid from Colorado who packed his MacBook. At the lodges where we stay each night, the kid sits down after dinner, puts his headphones on, and codes. Even on his 21st birthday, with a forgotten beer nearby, he's coding. He's working on an app, the third or fourth one he has written. He and Houghton quickly bond over apps and their mutual dislike of Zuckerberg. “I got off Facebook a few years ago,” says Houghton.

“Yeah, it's really just for old people now,” says the kid. “Our parents are on it. It's not the future anymore.”

The kid eventually describes the app he's been coding, a social-media tool that sounds a lot like Twitter. But Houghton is impressed with his ambition and work ethic. “You know,” Houghton says to me later, “given the right opportunity, he might end up doing some pretty awesome things.”