Forgotten stories of the great escape to Hong Kong across the Shenzhen border

Vast numbers of mainlanders fled across the Shenzhen border from the 1950s to the 70s, fuelling Hong Kong’s boom years, says Chen Bingan

Chen Bingan, a writer from Shenzhen, spent more than 20 years interviewing sources and compiling information on an untold story involving millions of people, which has now been published as The Great Exodus to Hong Kong. The book, which came out in October, documents an important but forgotten slice of history, when mainlanders fled en masse between the 1950s and 70s to seek better lives in Hong Kong. This enormous movement of people was long considered too sensitive to discuss until a few years ago, when mainland authorities first began to ease up on secrecy. Chen talked with the Sunday Morning Post about why such a large number of people left the mainland, how they did it and where they are today.

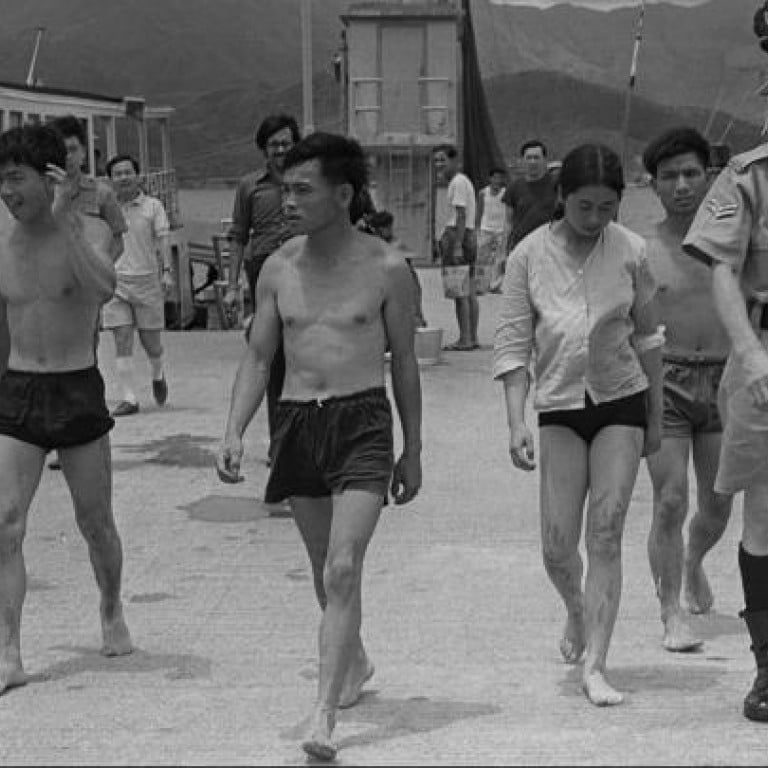

It all happened between the '50s and '70s, when Shenzhen was a small fishing village. Every single dark night during that time there were many mainlanders leaving their homeland, diving into the deep and dirty Dapeng and Shenzhen bays, and swimming the deadly four-kilometre journey to Hong Kong. The years 1957, 1962, 1972 and 1979 marked the four major booms in illegal emigration to Hong Kong, as mainlanders had suffered greatly from the Cultural Revolution, which included vast famine.

According to my research and investigations, about two million people flooded into Hong Kong as illegal immigrants, often with great personal loss, and more people died on their way or were caught and repatriated.

Neither East Germans climbing the Berlin Wall nor the tens of thousands of North Koreans crossing the Yalu River to the Chinese city of Dandong could compare to the exodus from the mainland to Hong Kong. It’s an epic account of the fate of communists seeking a better life in a capitalist harbour, at a cost of life and blood. So I called it The Great Exodus to Hong Kong.

How many refugees escaped successfully from Shenzhen to Hong Kong, and how did they make it?

There is still a lack of official statistics, because the incidents were documented in secret archives or considered too sensitive for mainland authorities to record, let alone publish publicly.

Some mainland media outlets and scholars say that about 560,000 residents from 62 cities and counties in 12 provinces escaped to Hong Kong between 1949 and 1974, according to documents released by the Guangdong archives bureau. Some Hong Kong media put the figure at about 700,000 people. But I found, by spending two decades interviewing refugees and researching a large amount of historical material scattered throughout the country, the real figure to be two to three times higher. Most of those who escaped were young, strong peasants, leaving behind their old and under-age family members in deserted villages in Guangdong. Others included city dwellers, students, educated youths, workers, soldiers and officials. The shortest and most popular escape route was to swim from the Shekou area of Shenzhen to Yuen Long in [northwest] Hong Kong. But it was also dangerous and often fatal, through drowning or being shot dead by People’s Liberation Army soldiers. There was even a job in Shenzhen that involved helping officials collect and bury the bodies of the countless people who failed to make it.

What drove you to work on this book?

The huge number of escapees was one of the main contributors to the booming Hong Kong economy in the '70s and '80s. And they were also the key to inspiring and spurring central authorities to start the reforms and opening up in Shenzhen.

In the '60s, Hong Kong started to embrace its booming manufacturing industry, with a rising demand for migrant workers, as millions of mainlanders arrived seeking better lives. This hungry army of refugees satisfied a rising city’s appetite for cheap labour.

The runaways were all good people who had been physically and spiritually tortured. To them, Hong Kong meant freedom, food and a future. They were humble and willing to bear the burden of hard labour; they forged the backbone of the working class in Hong Kong. They were the main support behind Hong Kong becoming the Pearl of the Orient and an economic power in Asia.

Additionally, in the late '70s, some of these runaways who became Hong Kong residents turned around and became the first batch of Hong Kong businessmen to set up factories in Guangdong. Because of the funds, advanced technologies and management experience Hongkongers brought in, the central government and Deng Xiaoping decided to make Shenzhen China’s first special economic zone, and the nation’s window to the world. And the reform and opening up followed.

The people who escaped to Hong Kong should have been engraved in history, but in reality, most of them were eventually forgotten and abandoned by most of society. Now they are old, retired labourers without a reputation or decent income.

Neither the mainland nor Hong Kong governments want to propagandise or memorialise the escapees, because of the associated political taboos. By April 1, 2007, about 12,000 documents about the people had been declassified and released by the Guangdong archives bureau. But, there are still very few documentaries, movies or novels about their careers and fates.

It’s extremely unfair, and I want to record their stories. Over the past years, I have interviewed hundreds of the escapees, and I will try to interview more of them. I also call upon authorities to launch projects to record the Great Exodus to Hong Kong.

What do readers think of the book?

My book is disputed among readers. Because of a lack of support and sources, I could only investigate and research the historical facts myself. Some Hong Kong scholars and readers think the true number of the refugees from the mainland, as well as their contribution to Hong Kong’s economic development, was not as great as I described.

But I am happy to see that such an issue can be controversial among the public. It helps society still remember people who tried their best to seek better futures and freedom at the cost of their lives and blood. Some of them were buried in unknown hills in Shenzhen, while some are getting old in Hong Kong and overseas. But I believe they are all heroes and should be recorded in China’s history.

Chen spoke to He Huifeng