Looking at the list of winners for best director, one can see that the many different juries of Cannes did a great job time and time again. A large number of names here are considered to be best in the craft. Here are the 25 selected to best represent the award.

25. So Close to Life (1958, Ingmar Bergman)

The two most critically acclaimed movies of Bergman’s career up to this point had already been released (“The Seventh Seal,” “Wild Strawberries”) and how does he follow that? By making an intimate minimalist drama about pregnancy.

Even in his weakest days, the Swedish master is capable of making a film worthy of discussion. The main element for which this feature is worthwhile is its remarkable ensemble of female actors. Bergman was one of those directors that understood and could enter a woman’s psyche and here the character study is done during their most intimate condition – during pregnancy.

The movie is filled with Bergman’s regular collaborators. Ingrid Thulin and Bibi Andersson, already experienced in working with the director, deliver potentially the best roles of their careers, both playing mothers scared of pregnancy and the future it will bring; the former because of declining family love, and the latter because of the idea of raising a child as a single mother.

However, the scene stealers are the rarely seen Eva Dahlbeck as a woman from a happy environment awaiting acquisition, and Barbo Hjort af Ornäs as a pillar of support and morale to all the mothers.

What earned the director the accolade is the scene of bringing a “newborn” to the world. All the pain, bate and strain are presented in those few minutes of agony. Filled with fascinating dialogues from all three main actresses, “Brink of Life” (a title by which the movie is also known) may not be one of Bergman’s trumps, but it is a film worth giving attention to.

24. Empire of Passion (1978, Nagisa Oshima)

Sex and violence have been trademarks of Oshima since the beginning of his career, again and again used to criticize traditional Japanese customs and culture. This time there is a twist, because a ghost story is thrown into the narration.

The first half-hour is intended for breaking taboos and for opposing the tradition with a repeated showing of the act of infidelity between a middle-aged woman (never looking younger or more beautiful) and her youthful lover. They are short, yet perverse and in your face. One particular scene shows us the shaving of the clitoris, and while the organ is not shown, deftly hidden behind the man’s body, the process in and of itself causes polemics.

While these scenes will return later in the story (once in a form of a rape), the ones from the first half-hour are all the talk. With the murder of the husband, the story shifts from one taking place in the realm of the senses to a kwaidan.

Here, Oshima is at his most beautiful and his creepiest. What begins is psychological torture with a dash of unnatural. The lovers suffer, but the effects are felt by the entire village while the ghost of the drunken man expects balance and justice. Blood will be splattered, the characters will be emotionally crippled, and the viewers will feel the full nuisance. And traditional Japanese folklore never was more beautiful than under the watchful eye of Oshima’s camera.

23. After Hours (1985, Martin Scorsese)

The 1980s were a strange period in the creative works of Scorsese. After the financial flops of hardcore auteur films (“Raging Bull,” “The King of Comedy”), the director had an interesting, if questionable, string: a sequel to a classic that nobody wanted, a music video for the King of Pop, and a notorious religious film depicting Jesus as a sinner.

Before all of them, Scorsese released his most atypical project: “After Hours” is a stylized, if bizarre, black comedy. The concept was always somewhat present in his works, but here it takes center stage. And, master that he is, he draws the best from it.

Like in “Come and See,” we follow a character for whom situations are changing, every next one being gradually worse (but luckily, unlike in “Come and See,” they don’t become brutal and soul-crushing) and he, lamentable, is forced to go through this because luck is absolutely not on his side. In one moment he even starts to accept his fate (“I’ll probably get blamed for that”), but that does not help his case. All the while, the viewers have a grin from ear to ear.

It is easy to enjoy the misfortune of others. All the characters, especially the supporting ones (that includes, among others, the bumbling idiots Cheech and Chong), give the best of what they got in giving Griffin Dunne’s character the worst night of a lifetime, while at the same time amusing the viewer. Once the movie makes a full circle you will be glad (partially) that Paul’s nightmare is finally over. At least for that night.

22. Nostalghia (1983, Andrei Tarkovsky)

Often ranked among the weakest works of Tarkovsky, alongside “Ivan’s Childhood,” “Nostalghia” still showcases a lot of things worthy of attention. It is probably the most sincere choice when, among his seven magnificent works, we have to choose one that is the closest to visual poetry. Or is this film already a visual poem? Needless to say, the film does not disappoint in this aspect.

Like the rest of his filmography, every shot is a story in and of itself, full of life, even if the world shown is somber. With this film, Tarkovsky, away from his home country at the time, expresses his craving for a home many miles away, personifying himself as the protagonist of the story, who is also in a foreign land longing for the “safety” of homeland.

The film honors the art of versification, filling the scenes with lyrical beauty that only the best of verses on paper can induce. Two scenes stick out in the mind: the self-ignition of the so-called madman on the town square while the impotent masses stay unfazed and Beethoven is playing (the agony of this, a scene worthy of a horror film, is felt even by the viewer); and a scene that comes shortly after, a nine minute uninterrupted cadre in which the poet transports a lit candle from one part of the drained pool to the other, giving honors to a recently departed friend, after which he collapses on the floor while a black dog keeps him company. Full beauty of moving pictures.

21. Ugly, Dirty and Bad (1976, Ettore Scola)

Right from the start, the film delivers what the title promises. A small, dilapidated, two-room house in, it seems, a Romani settlement near Rome. In the house, a family of more than 10 starts to wake up and we are greeted with screams, violent threats and karst. Humanity’s lowest. The impression we got initially remains till the end.

Scola, known for showing human relationships at their best, made a movie depicting the total opposite and out of his comfort zone. The men are pigs, least of all, and the women are reduced to sexual objects.

The film is vulgar and incorrect and bears that proudly, showing it surely and with nuance of surrealism. Fellini meets Waters. And we love it for that. The characters are many, but everyone gets enough screen time to show their “virtues.” There are whores, pussies, narcs, beggars, trannies, sicks, thieves – the types of people Travis would wash up from the street. Among them all, the scene-stealer is definitely the patriarch – one hypocritical piece of human waste, a potential culprit for how everyone ended up were they did.

It is a social critique, but primarily a comedy. A black one. Of the worst kind. You wouldn’t think that a slow death of a man in agony would make your stomach hurt from laughter, but here you are. We come to the question how the children, who are many, grow up in this hellish household. The answer – their future is grim (if the last scene is any indication).

20. All About My Mother (1999, Pedro Almodovar)

While entering an Almodovar film, one can expect eccentric characters; a story that is all over the place while at the same time being planned and focused; a warm and welcoming color palette; and an indescribable mix of all kinds of feels. “All About My Mother” delivers every trademark of the director in a double dose, and one can hate that or love it.

In this tale about loss, together on a screen we see a grieving mother, a transvestite, a lesbian actress, the actress’s heroin-addicted partner, and an AIDS-infected nun. A unique group, for sure, but from their interactions you will feel warm around the heart. This is a celebration of femininity, unity and friendship.

One of the many impressive things that Almodovar shows here is the ease of interactions that these actresses share with one another: one moment they meet each other, but right at the next a strong bond is established, so relationships are formed; mother-daughter, partner for life, a friend you can count on, etc.

Cecilia Roth is a pure enjoyment to watch; spending only a hour and 40 minutes with us, she almost effortlessly crafts a character that we feel like we’ve known our entire lives. Penelope Cruz and Marisa Paredes also deliver, giving memorable performances, but the star of the night should go to Antonia San Juan, who, despite a limited time on screen, steals every scene with her charm, stance and sweet-talk. Crying scenes are used sparingly, but once they hit, the hit hard. Welcome to Almodovar’s whimsical cabaret.

19. Fargo (1996, Joel Coen)

The Coens are definitely no strangers at Cannes, winning this award three times already. Once for the record-breaking “Barton Fink,” and the third for the noir revival “The Man Who Wasn’t There” (both worthy of a place on the list). Arguably, their greatest hour came with the second award. In a snowbound Minnesota, a real case happened. It would’ve been a perfect crime, were its perpetrators not, gently put, idiots.

“Fargo” is a pinnacle of irony, delicately stirring a grim story of a murder with subtle black comedy. First there is William H. Macy trying to get the oh-so-needed money, which he loses due to a set of stupid circumstances. The solution to return it back: by kidnapping his wife, of course.

For that he hires the never shutting-up Steve Buscemi (“I don’t have to talk to you either, man.”), probably in his full acting shine; and Peter Stormare, an unstoppable death machine (“And for what? For a little bit of money…”). The one who stands in the way of this scheme is Marge, the only sane person in the entire story, the basis of optimism and calculation and a delight to watch.

The most morbid scenes of the film (the kidnapping, the killing spree, the violence, the woodchopping remains) are the ones that bring the most laughs. Add into the mix the perfectly pulled-off accents from the northern Midwest, and you can be sure that watching this movie is time well spent.

18. Elephant (2003, Gus Van Sant)

“The movie could choose two desperate routes in presenting its story: 1.) Visceral, in which it is left to violence and is capable of exasperating and offending many people, covering media such as film, music, games and parading this data while the victims are motionless, or 2.) Manipulatively sentimental, where the performances of the creatures are perfect with ideal life, prematurely interrupted by the action of the evil pistol.”

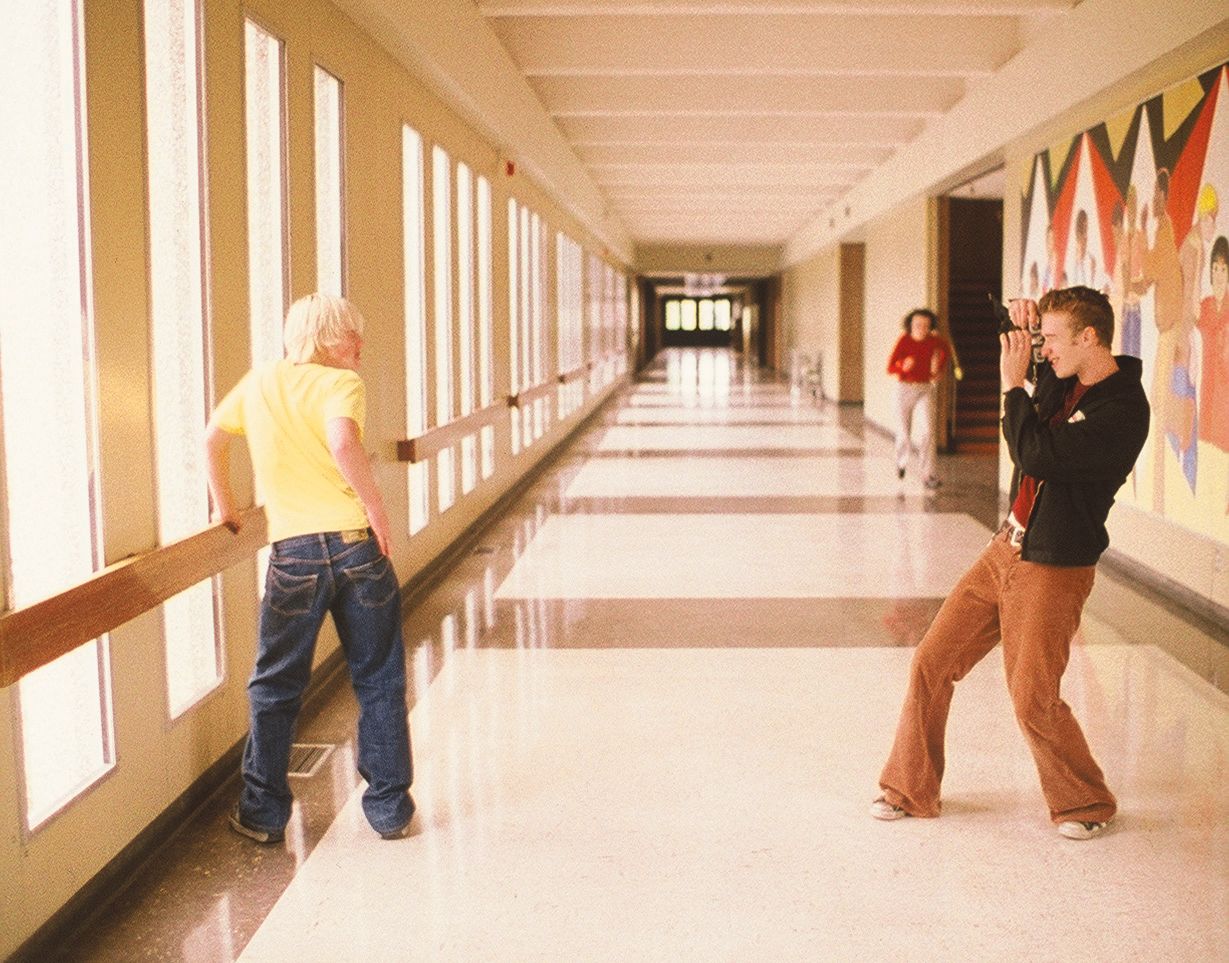

Fortunately, under the steady direction of Gus Van Sant, the film is neither. This accomplishment can be viewed as literal, but also metaphorical. Inspired (actually done) by true events (in this case Columbine), this film is a special and occasionally horrifying experience.

This impression is first contributed to by a specific shooting mode, where the camera is set to follow the characters from the back, creating such an effect to make you an actor in the story, better bringing you into the site and people who are there. The characters are another feature that make this film special.

At first glance they all look like cardboard clichés: there’s an athlete, a nerd, a popular girl, enthusiasts, traitors, discarded, those with family issues, etc. But as the film moves away and how the camera “alternately” implements the appointment of moments with them, you become more aware of them and they become what they truly are: children, with all virtues and defects, are real human beings.

Another thing I would like to mention as a big plus is that the movie is slow-paced (which is amazing for an 80-minute movie), gradually but intensively building the upcoming tension and neutrality it occupies, and if you’re informed of the above-mentioned event that inspired it, you know it’s crucial.

The film does not blame anybody, it does not take sides, it only shows the situation as it unfolds. It will do a lot without showing you much, but it leaves you to come to the conclusion yourself. One of these scenes is the very end of the film, underlined with a strong sense of frustration and indescribable sorrow. By the end, you have a feeling of waking from an awful nightmare and as much as you say it’s not true, this dream stays in your subconsciousness, ready to re-appear in the near future.