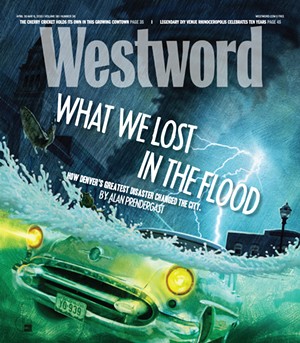

Those who lived through it will tell you that the spring of 1965 was not like other springs in eastern Colorado. From Fort Collins to La Junta, the land shuddered and groaned, afflicted with mini-earthquakes and baby twisters, freak hailstorms and gale-force winds.

But to say people should have paid attention is to wrap yourself smugly in half a century of hindsight. At the time, the bad winds and unfriendly skies were seen as mere anomalies, a little Wild West weather, nothing more. Nobody could anticipate what was coming because there had been nothing like it around here for generations, and the past was not much studied in these parts.

Yes, it was wet, but after three years of drought, the farmers welcomed the rain. June arrived gray and damp, more like a New York November than the parade of dry, sunny days and mild nights the citizens of Denver had come to expect. A cold front from the Northeast butted against the Front Range and camped out, entwined with a flow of warm, humid air oozing up from the Gulf of Mexico. The unholy coupling went on for days, blotting out the sun and generating bursts of what the meteorologists called “orographic precipitation.”

A few parched burgs got hosed. For the most part, though, the bank of dark thunderclouds just sat there over the mountains, swollen and ominous. Then the signs, the portents, became too violent to ignore.

On Monday, June 14, southeast Colorado Springs was hammered by golf-ball-sized hail. Fort Carson soldiers shoveled tons of the stuff out of basements in Stratmoor Hills. Funnel clouds were sighted to the north, and one tornado touched down in Loveland, smashing trees and cars.

On Tuesday, the rain and hail swept northeast, a procession of storms from Greeley to Sterling and on to the Nebraska line. The hail came so fast and thick that it blocked storm drains. Pawnee Creek and Lodge Pole Creek, both tributaries of the South Platte River, jumped their banks and submerged roads in Logan and Sedgwick counties. Sheep and cattle drowned, and areas of some towns were soon under three feet of water.A photographer in a helicopter described the bloated river as "a knife of mud, slicing across the green countryside."

tweet this

But all of that was just tuning up. The main event came on Wednesday, June 16, starting at about half past one in the afternoon. It began on the southern edge of Douglas County, with a hard rain and a tornado that ripped through the tiny town of Palmer Lake, peeling the roofs off thirty houses like so many soup-can lids. The twister scooped up water from the lake and dumped it into the houses, mixed with frogs, fish and gravel.

Then it went away. But the rain kept coming.

The rain was torrential. It was record-busting. It was biblical. It was as if a sword-swinging angel had cracked open the piñata of wrath.

Fourteen inches of rain fell on Dawson Butte, north of Palmer Lake, in four hours. The small, natural channels of the butte’s steep slopes couldn’t handle the runoff, so the water cut fresh ones. It did the same thing when it found its way to the gullies and streams below, overwhelming the banks and gouging new paths. “Creeks overflowed, roads became rivers, and fields became lakes — all in a matter of minutes,” wrote flood-watcher H.F. Mattai in a report to the U.S. Geological Survey.

On a family ranch south of Castle Rock, fifteen-year-old Jim Lowell waded to the barn to try to save the livestock. The water was up to his waist, then his chest. He climbed onto the barn roof to wait out the storm.

The rain pushed into Castle Rock. So did East Plum Creek, wiping out roads and bridges in its path. Lou Blanc, manager of the local Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph office, was inundated with complaints of downed phone lines. But Blanc had more immediate concerns about being inundated himself: Water was seeping under the door. It was raining so hard that it was difficult to breathe when you stepped outside, like you were standing under a waterfall. Blanc and the boys set to work ripping up the saturated front lawn and packing the sod outside the door as makeshift sandbags.

Then four linemen reported back to the office. They told Blanc they’d just saved an elderly couple from a half-submerged car on U.S. 85, using a winch to tear off the car’s roof.

The east and west branches of Plum Creek joined forces just outside Sedalia. Around five in the afternoon, the combined surge swallowed the town’s main street, including seven homes, a church and the grange hall. The creek, typically no more than a few feet wide on its best days, now stretched over an expanse of nearly a mile as it headed north.

It was difficult to measure the full force of the runoff. The gauging station at Louviers was swept away. But later calculations indicated that the flow of Plum Creek increased a thousandfold in less than three hours, from 150 cubic feet per second to 154,000 cubic feet per second.(A discharge of one cubic foot per second amounts to about 450 gallons a minute.) North of Louviers, the raging creek poured into the roiling South Platte and became an Irwin Allen production. A photographer in a helicopter described the bloated river as “a knife of mud, slicing across the green countryside.”

It was no longer simply a flood. It had leapt in rank to a hundred-year flood, or even a five-hundred-year or thousand-year model, a millennial event. State patrol officers reported a wall of water estimated to be twenty feet high headed for Littleton, carrying in its wake a tangle of trees, asphalt, cars and other debris, with a second crest not far behind.

The beast was expected to hit downtown Denver at eight that evening.

It would be the darkest night in Denver’s history, a night of destruction far exceeding anything the city had ever known. The ’65 flood claimed 21 lives and resulted in property losses statewide estimated at $543 million — adjusted for inflation, that’s more than $4 billion in 2015 money — with the worst damage in the Denver metro area. Other floods in the state’s history have resulted in a greater loss of life; the Big Thompson flash flood in 1976 killed 143 people, while the death toll from a 1921 flood in Pueblo has been set as high as 1,500 people. But no natural disaster has had a more profound or lasting impact on state policy — or in shaping the Denver we know today.

The flood ravaged hundreds of homes and all but obliterated dozens of businesses; many never recovered. But it also triggered a painful re-examination of a century of haphazard growth and myopic planning, during which the city had abused and poisoned its main waterway and ignored the communities on its banks. The disaster became a trigger for long-delayed flood-control projects, ambitious urban-renewal plans and a bitter diaspora for longtime residents of Auraria.

It was also the start of a renaissance along the South Platte itself. What was once the city’s greatest eyesore is now its showcase. But the transformation of the river didn’t occur overnight, or even over a decade. It took the determination of many officials, businesses, philanthropists and volunteers, as well as a still-evolving discussion of what the city lost — and found — in the flood.

“With a massive stroke the South Platte, the funny, forgotten nothing of a river, remembered itself to everyone,” wrote former state lawmaker Joe Shoemaker in a 1981 account of his post-diluvian battle to clean up the river. “A century of disrespect and disregard had been revenged in a few unforgettable hours.”

Shoemaker’s son Jeff succeeded him as executive director of the Greenway Foundation, the nonprofit that has become the river’s champion. He talks about the flood’s impact in similar terms. “On one day, the river gave back to Denver what Denver had been giving it for over a century,” he quips. “It just said, ‘Here — take it back.’”

Denver got its start on the river, at the confluence of the South Platte and Cherry Creek. In 1858, the first significant gold strike in the area was made several miles farther south on the Platte — and petered out quickly. But that didn’t stop prospectors and land speculators from setting up competing settlements on opposite sides of Cherry Creek and giving them fancy names. Auraria. St. Charles City. Denver City.

Within a few years it was all one boomtown, building out from the confluence and crowding out the Arapaho and Cheyenne from their seasonal encampments. The departing natives offered the white men some friendly advice: Don’t build so close to the water.

The riverbed might look dry, they explained, but it wasn’t always that way. Every few years Cherry Creek got a notion to jump its shallow channel and raise hell. The Platte, too, went berserk now and then. Back in 1844, the river had risen twenty feet, sweeping away everything in its path.

The white men didn’t believe it. The white men weren’t around in 1844. To them, the Platte was a sorry, sickly excuse for a river, nothing at all like the Mississippi, the Missouri, the Arkansas. Mark Twain described it as “the shallow, yellow, muddy South Platte, with its low banks and its scattering [of] flat sand-bars and pigmy islands — a melancholy stream straggling through the centre of the enormous flat plain.”

The white men had traveled across the Great American Desert. Snow on the distant peaks aside, they knew that Denver City, or whatever you wanted to call it, only averaged a few inches of rainfall a year. It did not occur to them that in the desert you sometimes get ten years of rain all at once.

The white men didn’t believe any of it. The white men were idiots.

The city was scarcely five years old when the inhabitants got their first taste of what the Arapaho were talking about. In May 1864, after several days of rain and heavy snowmelt, Cherry Creek barreled through the heart of town like a tsunami. It took out the Larimer Street bridge and the Blake Street bridge and swept away the city hall. It almost claimed the night shift of the Rocky Mountain News, too; founder William Byers had set up his shop in the creekbed, the better to serve both sides of the Denver-Auraria rivalry. Staffers had to make their way to shore with the aid of ropes thrown by rescuers. At least fifteen people died that night, and businesses were buried in up to twelve feet of mud.The departing natives offered the white men some friendly advice: Don’t build so close to the water.

tweet this

Cherry Creek overran its banks again in 1875. And in 1878. And four more times in the next fifty years. By the time of the 1912 flood, the city fathers had put up retaining walls and greatly improved the channel, but it still wasn’t enough to contain the creek’s tendency to raise hell. Cattle and mill baron John Kernan Mullen, who lived downstream from where the improvements stopped, filed suit against the city for turning its back on the residents of “the Bottoms” in its flood planning.

A dam built in Castlewood Canyon in the 1890s was supposed to help tame the creek. But in 1933, the Castlewood Dam failed under heavy rains, sending a fifteen-foot-high wall of water toward Denver, 35 miles away. Thanks to heroic efforts to send out the alert, 5,000 people were evacuated in its path; only two died.

The creek continued to menace the city until the completion of the Cherry Creek Dam in 1950. But curiously, little was done about the South Platte itself — even though several of its other tributaries were almost as unpredictable as Cherry Creek. A 1945 study had recommended building a dam and reservoir southwest of the city, where Plum Creek converged on the Platte. In 1950, the proposed Chatfield Dam was authorized by Congress, but the project stalled out. Property owners in the area didn’t want the dam, and there was little political will to build it.

And why would there be? Over the first century of Denver’s existence, the South Platte had mustered only one notable flood, in 1885. Most residents paid little attention to the river and what went on there. Since the 1870s, it had been a place of factories and rail yards, a dumping ground for whatever the city didn’t want: animal carcasses and human waste, used oil and old tires, rejected feathers from a pillow factory, paint and wood shavings, and effluent from dozens of other plants.

By the 1960s, half a dozen landfills had been created along the river. No fewer than 250 drains poured directly into it, spewing storm water and salt from city streets, unknown gunk and sometimes raw sewage. Its banks were choked with weeds, abandoned cars, hobo camps and trash. It was an open sewer flowing through an industrial wasteland, flanked by the city’s poorest neighborhoods — places like Globeville and Sun Valley, Lincoln Park and Valverde and Overland.

The locals had learned their lesson about Cherry Creek. But not the South Platte. The river had no advocate, no guardian, no constituency. Its festering problems, like those of a broken toilet, weren’t something you brought up in polite company. It’s not as if the succession of city leaders who ignored it had a clear picture of what was to come. Not one of them had a crystal ball, a way of seeing the consequences of their arrogance and indifference. Not one had the foresight of Louis XV, who was said to have summed up the impending fate of the House of Bourbon in four little words.

Après moi, le déluge.

By five in the afternoon of June 16, 1965, the Denver Police Department had cleared its radio traffic for emergency calls only. News of the flood’s shambling progress from Castle Rock to Sedalia was all over the broadcast channels, though the reports didn’t do full justice to the devastation it was leaving behind. Now the race was on to get people to high ground and close off all the bridges that spanned the river. Police officers knocked on door after door of homes and commercial buildings along the river, urging occupants to get out while there was still time.

For all its tremendous force, the wall of water rumbling into town was only one concern. Even more worrisome, perhaps, was all the hazardous material in its debris flow. As the flood roared from the relatively unpopulated countryside to the outskirts of the metro area, it helped itself to fuel storage tanks along Santa Fe Drive. Then heavy equipment from the rail yards. Then mobile homes from trailer parks in Littleton and Englewood. Then once-stationary houses of brick and wood, foundation and all, not to mention a devil’s brew of cement chunks and old cars and junked appliances and the contents of landfills along its banks.

The water cut a wide swath, making quick work of the Centennial racetrack. Most of the thoroughbreds had already been vanned out, but the flood buried the stables in mud. Meanwhile, the debris in the core of the current smashed against the river’s bridges like a battering ram. Radio reporter Bill Gagnon watched the old Hampden Avenue bridge buckle, telling listeners, “It looked like an entire lumberyard was jammed up against the bridge.”

Three men watching the demolition from the riverbank found themselves chin-deep in water when the bridge collapsed. National Guard troops pulled them out. Gagnon hustled to interview them, wondering how long the rest of the city’s bridges would last.

Standing on top of Ruby Hill with his wife and a clutch of other sightseers, Denver Post staffer John Buchanan watched an enormous butane tank narrowly clear the Florida Avenue bridge. Then trailers got pinned against the bridge. Then a small house. In addition to the roar of the water, there was a constant grinding sound as one object after another joined the scrum. Buchanan saw explosions and flames rising to the south and “something that looked like skyrockets” in the sky above the Gates plant, even as much of the city was going dark from downed lines and swamped power stations.

One by one the bridges fell, all the way to the Colfax viaduct, which miraculously held. (The Evans Avenue bridge survived the night but collapsed two days later.) The flood knocked out thirteen of the 24 spans across the river. At Sixth Avenue and Platte River Drive, two large butane tanks ruptured under the assault; the explosion could be heard for miles. As the night dragged on, police and firefighters eyed the tanks and other debris piling up under the 16th Street viaduct, smelled the seeping gas, and wondered if the structure would last through the night. It did, but just barely.

Among the hardest-hit areas were the Valverde and Athmar Park neighborhoods. The Valley Highway at Alameda Avenue was soon submerged, the river quickly spreading out across Alameda from Santa Fe to Tejon Street and beyond. A boxcar smashed into a building on South Jason Street, and firefighters watched in frustration as two warehouses caught fire, a moat of turbulent water around them. Seven people were spotted inside a nearby building and on its roof. Denver Fire Chief Cassio Frazzini and one of his fire captains, Robert Hyatt, tried to reach the stranded group in a rowboat.

The current was too strong. The boat capsized in the middle of Jason Street. Although the water was only four feet deep in some areas, it was moving too fast for the chief to stand up. Frazzini held on to a pile of debris that had made an island in the torrent. Hyatt hugged a tree. It took the fire crew another two hours to rescue them and the seven civilians, using another rowboat, powerboats and ropes.

An even more dramatic maritime rescue went on for most of the night just a few blocks up the street. A telephone company test deskman named Kenneth Fisher was helping his grandmother evacuate on the west side when he heard a police radio call for a boat, any boat, in the vicinity of Alameda and Santa Fe, where officers had seen flashlight signals for help from someone on top of a sign at the Gaslight Motel. Fisher got his grandmother resettled, then headed out with his motorboat in tow.

At Alameda and Tejon, which had become an informal dock heading down into the heart of the flood, Fisher introduced himself to two police officers, Jack Peachey and Robert Bott, explaining that he had some experience boating rapids on the Colorado River. Shortly after midnight, the three of them launched into the murk.

The current was fast, the waterway mined with trees, cars and pieces of houses. Fisher had to tack from the north to the south side of Alameda and back again to keep from being carried away by the current. Rubble battered the boat repeatedly, but Fisher somehow kept her steady. Once at the Gaslight, he pulled up close to the side of the motel while the officers, armed with flashlights, helped three men off the sign and into the boat.

Accounts vary as to how many lives Fisher, Peachey and Bott saved that night. Some newspaper summaries say six. An account written by Fisher says sixteen. What is clear is that after getting to high ground with the men from the Gaslight, they went back for more. They heard voices from on top of a store, where the wall had been washed away and water was cascading over the opening like a waterfall. They took on three passengers and headed back to the Tejon dock. The water was ten feet deep, fifteen at some points, and the boat scraped over the tops of cars. They went back into the flood, drew up to the second-story window of a frame house, and saw a middle-aged couple and an elderly woman playing cards by candlelight. They collected them over the old woman’s protests. The house washed away later that night.

They pulled a shrieking teenage girl from the top of a flooded garage and picked up two men and a woman at another motel. After that, they put the boat on a trailer and took it to 47th and Sherman and rescued a family of three from their home. At one point they went into a coffee shop, muddy and bedraggled, and ran into Denver mayor Tom Currigan, who asked the officers to deliver a full report to him. The letter signed by Peachey and Bott praises Fisher’s courage and nautical skills: “We feel proud to have been of assistance to this caliber of a man.”

Just as predicted, the flood muscled into downtown Denver around eight. Unlike the bridges to the south, most of the viaducts survived the pounding. But the flood had its way with the rail yards, the Tivoli Brewery, the warehouses and modest homes of the Bottoms west of downtown. A call went out concerning forty brand-new cars, swept out of a garage at Fourth and Walnut; anybody who happened to see them floating by was urged to contact the Ford Motor Company. The power outages spread. Some television and radio stations went silent, while the Rocky Mountain News was forced to use the printing presses at the Denver Post to get out the next morning’s sodden disaster coverage.

Tasked with closing down all southbound traffic on I-25 and diverting those trying to use the bridges, the police had little time to worry about looters. But not much crime was reported other than a midnight raid on the Jonas Brothers fur repository on Broadway. The bigger problem was all the rubberneckers going down to the river, absorbing the horrific spectacle of houses floating by and bridges collapsing. The gawkers were heedless of the downed lines, gas leaks and other dangers. The cops begged the radio stations that still had power to get the word out: Go home. Nothing to see here.The Valley Highway at Alameda Avenue was soon submerged, the river quickly spreading out across Alameda from Santa Fe to Tejon Street and beyond.

tweet this

And after a while, there wasn’t anything to see hardly anywhere. Harold Price, main district plant superintendent for Mountain States Telephone, headed downtown on the 14th Street viaduct at half past four in the morning, after the floodwaters had begun to ebb, and saw a city plunged into darkness. He could make out the shapes of boxcars flipped over in the train yards, but there were no streetlights. The police were directing traffic with flashlights.

Dawn revealed a Denver with a suppurating brown wound snaking down its middle. The downed bridges from Douglas County to Colfax left thousands of people stranded, with no way to get home. Cars were gone, never to be seen again; houses, too, in some cases. In all, 1,720 buildings in the city were destroyed or damaged by the flood. Trash, twisted metal and ruined furniture lined the streets by the river, along with a thick coating of mud, a fine and repugnant silt that had the color and adhesive quality of melted milk chocolate.

Jim Lowell made it off the barn roof, but his prize calf was found drowned more than ten miles downstream. Livestock losses were heavy. People also reported seeing human bodies in the flood, but with phones dead and power sporadic, deaths were difficult to confirm. Richard Andrus, 21, was killed when his light plane crashed in the storm. Linda Rae Beeman Rein, thirteen, died in a flash flood in the foothills west of Loveland. Adam Haffnieter, 69, died of a heart attack at the height of the flood. David Wilson, 21, a Bible student, went missing when the collapse of earthen dams inundated the small cabin where he was sleeping near Cripple Creek. Other casualty reports trickled in over the next few days, as the storm front and flooding shifted to the Arkansas Valley, prompting evacuations from Pueblo to Dodge City, Kansas.

The flooding on the plains had its own moments of drama. In the tiny town of Deer Trail, a couple headed back to Denver found themselves stranded in their truck on First Street, the flood water swirling around them. When it reached the seat, they climbed up on top of the cab. A man in a hotel across the way saw the expression on their faces as a 5,000-gallon gas tank came bobbing their way. Locked in each other’s arms, they kissed each other goodbye. But at the last moment the current pulled the tank away from them. It grazed the back of their truck and headed downstream.

It all could have been much worse. If not for the construction of the Cherry Creek Dam, the deaths in the Denver metro area could have numbered in the hundreds. The reservoir rose sixteen feet the night of the South Platte flood, but the dam held.

Four days after the flood hit Denver, President Lyndon Johnson declared 27 counties in Colorado a disaster area. Colfax was jammed with traffic for weeks as dazed commuters tried to figure out how to navigate their broken city. Volunteers, including Ann Love, the governor’s wife, worked long hours at Red Cross shelters and Salvation Army depots; neighbors pitched in to scour mud out of homes and get businesses back on their feet. But it was clear that things couldn’t go on as they had before. The river had spoken.

The flood “forced us to look at the Platte River Valley, and challenged us to do something about it,” Mayor Currigan observed. But people had very different notions of what that something might be.

The first priority, the one point of agreement among civic leaders, was the need to jump-start the long-delayed proposal for a dam at the southwest edge of the city. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began work on the massive Chatfield Dam in 1967 and completed it in 1975. During its construction, the South Platte flooded twice, in 1969 and 1973; though neither event approached the sheer fury of the ’65 disaster, they both underscored the need to take the river seriously. The Corps leased the area surrounding the reservoir to the state. Ironically, the dams at Chatfield and Cherry Creek, erected with great reluctance and with the principal aims of flood control and water storage, have produced the two most heavily used state parks in Colorado.

An equally significant development was the 1969 creation by the state legislature of the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District. An independent agency spanning six counties, the district represents a metro-wide approach to floodplain management that has become a national model of multi-jurisdictional coordination.

“Drainage doesn’t respect political boundaries,” says Kevin Stewart, the manager of UDFCD’s flood-warning program and information services. “The ’65 flood was really our birth. An ad hoc group of county engineers got together and said we needed a uniform way to deal with flood control in the Denver metropolitan area.”

Mayor Currigan, for his part, pushed for an array of redevelopment projects along the trashed-out Platte River Valley. His planning team came up with a handsomely illustrated brochure, “In Response to a Flood,” that invited readers to imagine “a beautifully sculpted channel with inviting walkways…new and modern industrial parks throughout the valley…. Picture old Auraria at the confluence of the Platte and Cherry Creek, and a separate village when Denver was founded, transformed into a vibrant urban college.”

The vision also included a “stadium complex or a college-oriented technical center,” a “magnificent” transportation museum, and the most fascinating “cultural-historical center in the nation, with museum, theater, and living pageants which bring our Indian, Spanish and Yankee heritage back to life.”

The brochure outlined 35 projects in all, at a staggering cost of $650 million. Most of the money was supposed to come from various urban-renewal funds, but Denver would be on the hook for more than $80 million in new bond debt. The city put together a task force with an optimistic acronym, SPARC (South Platte Area Redevelopment Committee), but it went the way of most committees — lots of memos and no action. There was no spark, and soon no SPARC, either.

Other than the Forney Transportation Museum — occupant of the Denver Tramway powerhouse prior to the arrival of REI — only one major component of the redevelopment plan ever became reality. In the late 1960s, the Denver Urban Renewal Authority mounted a skillful campaign to convince voters that the Auraria neighborhood was hopelessly blighted, with three-fourths of its housing stock “dilapidated or damaged beyond repair,” in part because of the flood. Actually, less than half of the area had been impacted by the flood, but many civic leaders were inclined to eradicate as much of the Bottoms as possible and start over. A bond issue to create the Auraria campus narrowly passed, leading to contentious condemnation proceedings and the dispersal of a core of “displaced Aurarians” who still mourn the loss of their neighborhood.

Local historian Gregorio Alcaro, whose grandparents operated the Casa Mayan restaurant out of their Auraria home for decades, notes that DURA was racing against a growing movement toward historic preservation in lower downtown and elsewhere, starting with the birth of Larimer Square. At the last minute, several Auraria landmarks were saved from the bulldozers, including the Tivoli, St. Cajetan’s Catholic Church and the modest nineteenth-century homes along Ninth Street Park. “The timing was so close,” Alcaro says. “If the flood hadn’t happened, the momentum could have gone in a different direction. The river had a lot of problems; it needed improvement. But they didn’t incorporate the community that was already there.”

Despite all the studies and proposals, for several years after the flood the city’s riverfront remained a grim, inaccessible place. Its rehabilitation was gradual and roundabout and owes a great deal to one man’s ability to break through the red tape. Joe Shoemaker had been Denver’s manager of public works in the early 1960s, back when city officials treated the river as a dump. After the flood, he began to think about it in other ways. He sponsored the bill that created the UDFCD and would later become the agency’s lawyer.

“It was the flood that really opened Joe’s eyes,” says Jeff Shoemaker. “He had great guilt — unnecessarily, I feel — because of what had been done to the river when he was manager of public works. Well, when you tore up a road, where did you dump the rubble?”

Joe Shoemaker left the legislature and ran for mayor. He lost. But one day in 1974, a full nine years after the flood, he walked into the office of Mayor Bill McNichols without an appointment and asked him what he planned to do about the river.

“It’s funny you should ask,” McNichols said.

The mayor had $1.9 million in leftover federal revenue-sharing funds that he’d tagged for river improvements. He wanted Shoemaker to head a committee that would figure out how to spend it — and how to get more money.

This was not SPARC. Shoemaker assembled a bipartisan group of community activists and businesspeople, including Dana Crawford, Hiawatha Davis Jr. and Daniel Trujillo. The seed money went to construction of the original Confluence Park and another modest riverfront park in Globeville. It wasn’t much, but people wanted more of it. The committee evolved into the Greenway Foundation, a nonprofit that would end up working with foundations, municipalities, state lottery funds and any other sources available to advance the cause."If we had more than a foot of rain in six hours, we could have a major event."

tweet this

Piece by piece, the waterfront got a makeover. Shoemaker worked closely with UDFCD on projects designed to improve water quality and flood control while making the river a safer, more attractive place. “Those are the guys that make shit happen,” says Jeff Shoemaker of the agency. “What I call a multi-use recreational trail, they call a flood-channel maintenance road. What I call a beautiful natural area, they call a flood-control detention pond. We’ve shown that you can get multiple bangs from a single buck.”

Starting with McNichols, city leaders began to see the river as an asset worth cultivating. Federico Peña came up with a Central Platte Valley master plan that consolidated rail lines and removed several viaducts, making the river more accessible and changing the warehouse district into something called LoDo. Wellington Webb declared 1996 the Year of the River and advanced the central greenway by leaps and bounds, including the dedication of Commons and Cuernavaca parks. Family attractions, such as the Children’s Museum and Elitch’s, suddenly saw the value in locating close to the river — and so did the people behind the Pepsi Center and Coors Field. Sports bars, fancy restaurants and high-rise condos also began sprouting nearby.

Over the past forty years, the Greenway Foundation has been involved in the construction of more than a hundred miles of hiking and biking trails along the Platte and its tributaries; the creation of more than twenty parks, including ten built on former landfill sites; and a total of $130 million in cleanup and improvements, including eight projects under way now that are expected to be completed in 2018. “That $130 million is directly related to, and responsible in great part for, over $13 billion of economic development right alongside the river,” Jeff Shoemaker says.

Joe Shoemaker died in 2012, on his 88th birthday. This June marks not only the fiftieth anniversary of the flood, but Jeff’s 34th year with the Greenway Foundation. He plans to celebrate both events with a rafting flotilla of dignitaries and volunteers down miles of the revitalized river, possibly hijacking the patio at My Brother’s Bar at its conclusion.

“People just assume that the river’s always been nice,” he says. “People assume it just happened. But the guy who gets the credit for that isn’t the guy you’re talking to.”

People also assume that the river and its tributaries have now been tamed, thanks to decades of flood-control efforts. That isn’t necessarily so. “Big floods are always going to happen,” says the UDFCD’s Stewart. “It would be a stretch to say Plum Creek could cause that kind of damage now. But we could get a large flood out of the metro area. If we had more than a foot of rain in six hours, we could have a major event.”

Stewart points out that downstream from Chatfield are less-controlled Platte tributaries. During the 2013 floods, the flow of Sand Creek peaked at around 17,000 cubic feet per second. One of its tributaries, Westerly Creek, overflowed its banks and inundated open space in Stapleton. “We do have dams to protect us that we didn’t have before, but there’s always the chance that something larger could occur,” he says.

Filmmaker Marshall Frech has made documentaries for public broadcasting about flash floods in Texas and the policy failures that have contributed to some of the nation’s worst flood disasters. For the past several years, he’s been working on a project about flood risks along the Front Range. Colorado is a good place to study “big storms stalled along mountain fronts,” he says — such as those that caused the 2013 Boulder Creek and St. Vrain Creek floods, the 1976 Big Thompson flood, the 1965 South Platte flood. He sees a pattern to many western floods: people lulled into a sense of complacency by the supposed lack of rainfall in a semi-arid climate.

“Even people who’ve grown up here somehow have it in their psyche that rain is going to come with more consistency,” he says. “But almost every year, we’re going to get a lot of rainfall in just a few events.”

And sometimes those events are apocalyptic. “The 2013 event sticks out to me because of how rapidly we’re able to throw those roads back in place now,” Frech says. “It had a really quick response. But did we make significant changes? That remains to be seen.”

Out here in the dry creekbed, our notions of risk keep changing. In 65 years, the spillway of the Cherry Creek Dam has never been tested; the normal pool of the reservoir lies sixty feet below it. But the once-rural area below that has been built up considerably, raising the expected death toll if something ever did go wrong. Hydrologic engineers no longer plan for hundred-year floods but a dreaded rare event known as a PMP, or “probable maximum precipitation.” The Army Corps of Engineers is now engaged in a four-year, $4 million dam safety modification study for Cherry Creek that conjures up a scenario in which a PMP of 24 inches of rain falls in a three-day period. The result is a three-foot overtopping of the dam, which is not good.

The odds against such a catastrophe, the Corps assures us, are 90,000 to one. Yet what are probabilities, except our way of trying to paper over what cannot be absolutely known? Fifty years ago what could not happen, what no one believed ever would happen, did. Imagine two days of rain like the one that started it all in 1965, and we are there, like Noah, back in the flood again.