Abstract

Financial misconduct has come into the spotlight in recent years, causing market regulators to increase the reach and severity of interventions. We show that at times the economic benefits of illicit financial activity outweigh the costs of litigation. We illustrate our argument with data from the US Securities and Exchanges Commission and a case of investment misconduct. From the neoclassical economic paradigm, which follows utilitarian thinking, it is rational to engage in misconduct. Still, the majority of professionals refrain from misconduct, foregoing economic rewards. We suggest financial activity could be reimagined taking into account intrinsic and prosocial motivations. A virtue ethics framework could also be applied, linking financial behavior to the quest for moral excellence and shared flourishing. By going beyond utilitarian thinking and considering alternative models, we offer a fuller account of financial behavior and a better perspective from which to design deterrence methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Illicit practices accompany financial markets throughout history. While some work hard to develop innovative products, others develop schemes to defraud clients and reap a quick profit. Manipulation, corporate misconduct, outright fraud, and white-collar crime came into focus once again after the 2007–2009 financial crisis. In response, governments arrived at a renewed recognition of the need for institutions and tools to deter agents from exploiting the freedom of markets illegally. Deterrence methods rely mainly on the theory of subjective expected utility (SEU) that describes criminals as rational utility maximizers (Becker, 1968). In modern psychology, such behavior may be characterized as extrinsically motivated (Amabile et al.,, 1994), focusing on material goods for the actors themselves, not others (Batson, 2011). Financial accounting practice describes this behavior as having a positive “net present value” (NPV). Economic actors choose extrinsically motivated actions that maximize their own utility; hence, governments try to impose a cost on perpetrators of misconduct that would outweigh benefits.

This paper considers the enforcement efforts of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), a key regulator in the global financial market. We show how the current model of market supervision exemplifies the subjective expected utility (SEU) logic to deterrence. According to Yeager (2016), deterrence requires that penalties be severe and consistent in order to change the incentives of individuals and groups. Indeed, the total amounts ordered in penalties and disgorgements as a result of SEC enforcement activities have increased eightfold over the last three decades, from about $0.5 billion to over $4 billion per year (Steinway, 2014; US SEC, 2020a). However, despite these efforts, deterrence effects appear limited (Yeager, 2016). Punishment is turning out to be ineffective in curbing financial misconduct (Ciepley, 2019).

The main aim of this paper is to amplify the study of corporate misconduct by demonstrating the ineffectiveness of monetary penalties following the utilitarian logic in deterring crime in certain cases. We present evidence from the US financial market, which has been a reference for financial markets around the world. In the illustrative case we analyze, the economic benefits that accrue to perpetrators outweigh the costs and harms, yielding a positive NPV under any reasonable scenario. Due to unavoidable limitations in enforcement, in at least some cases crime pays in SEU terms.

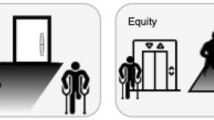

As a consequence of the above, we address a second aim: we attempt to explain why more financial agents do not commit crime given that “crime pays.” Apparently, the SEU framework does not accurately describe the human motivational system in general, nor specifically in financial activities. There are other reasons besides net economic gains for oneself that incentivize human action in finance, just as in other realms. A more comprehensive and accurate description of motivations from psychology, including intrinsic and altruistic motivations (Eisenberg et al., 2016), could contribute to improvements in deterring financial misconduct. Further, we would like to consider the rationality of financial activities from the viewpoint of virtue ethics (Sison et al., 2019), which examines not only utility and motivations but also the moral excellence of actors in relation to flourishing (Grant et al., 2018). Thus, we propose alternative models that extend from punishments and incentives (utility), through motivations, to the virtues to encourage fair and honest dealings in finance.

In light of the above-mentioned aims, the expected contributions are threefold. First, we hope to present some evidence for the ineffectiveness of financial crime deterrence exclusively focused on the utility approach. We apply the financial method of NPV in the analysis of misconduct to show that perpetrators secure gains despite fines and disgorgements. Second, we would like to present an alternative account of financial activity that bears in mind other motivations besides the extrinsic. That would open the door to a third contribution: the introduction of virtue ethics as a better explanation or rational model of financial activity that may curb illicit practices and promote honest behavior.

This is not a paper offering specific policy recommendations to curb financial misconduct. That would be too much to expect from the analysis of a case. Rather, it is a critique of the underlying utilitarian-economic rationality of the current legal regime. Neither is it a paper on how motivational theories apply to finance and inform particular behaviors. We would simply like to indicate that a motivational approach provides a better alternative to utilitarian-economic rationality in deterring financial misconduct. Likewise, this is not a purely theoretical paper on the precise way virtues are to be practiced in finance, following insights from Aristotle or MacIntyre, for instance. Too many intermediate issues would need to be settled first before such an attempt. Instead, we would merely like to broach this possibility as perhaps being a superior one, insofar as the virtues and the common good of flourishing combine both intrinsic and altruistic motivations, among other reasons.

The article is organized as follows. Section II defines corporate financial misconduct and presents the enforcement efforts of the US SEC. Section III frames financial misconduct as a rational decision according to the NPV method, discussing the benefits, costs, and the discount rate to be considered in illicit projects. Section IV analyzes a case of financial misconduct from the USA committed by a broker and applies the NPV method to illustrate the economic rationality of his actions. Section V presents a discussion of the findings from the perspectives of utility, motivations, and the virtues. Section VI outlines the implications for policy makers and managers. Section VII offers our conclusions.

Corporate Financial Misconduct

Corporate financial misconduct is generally addressed by civil law and involves civil statutes, although specific provisions may involve criminal penalties (Hanlon, 2009). Consequently, the use of the word “crime” in references to cases of fraud or money laundering, as it occurs in the media (Henry, 2017), is somewhat misleading. In fact, the wording used to describe such events varies from actor to actor (Vadera & Aguilera, 2015). Academic literature resorts to relatively neutral terms such as “corporate litigation” (Arena, 2018; Haslem et al., 2017) and “corporate misconduct” (Karpoff et al., 2017; Kedia & Rajgopal, 2011; Liu, 2016). When a study is devoted to a specific type of infraction, the authors tend to use terms defined in the statute considered. In the USA, securities fraud and accounting fraud is litigated under the Investment Companies Act of 1940, the Securities Act of 1933, or the Securities Exchanges Act of 1934, and the rules issued pursuant to them by the SEC. Misconduct by investment advisors falls under the same statutes and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Brokers can be disciplined by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), a self-regulatory organization. Corporate corruption in non-US jurisdictions involves the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (Schwartz & Goldberg, 2014).

Crime is not easily attributed to corporations, because crime is assumed to fall within the domain of individual human beings (Salinger, 2013, p. 219). First, punishment for criminal offenses involves sentences of incarceration or probation that can only be applied to individuals. The only type of punishment that can be ordered in the case of a corporation as a juridical person is a fine. Second, corporations are structured in a way that obfuscates responsibility and complicates the attribution of blame (Ciepley, 2019). Third, the pain of the punishment is not borne by the corporation per se, because it is not a real person. The punishment may result in layoffs and harm employees who had nothing to do with the crime. Corporate losses may hurt shareholders—including shareholders who did not own stock when the crime was committed—employees, and others saving for their retirement who have limited influence on the actions of the corporation. In sum, it has long been recognized in corporate litigation that the design of penalties is a complex problem (Coffee 1981).

Unless specific individuals can be identified as offenders, corporate offenses can rarely be enforced through the criminal justice system (Ciepley, 2019). The Federal Justice Statistics (US Department of Justice, 2017) published the following statistics: federal courts tried 8455 fraud cases in 2014, of which only 74 resulted in an order to pay a fine, indicating a possible corporate defendant. Thus, criminal cases do not typically involve corporations, despite the longstanding US legal tradition of treating corporations as if they were legal persons.

When corporations cause harm to individuals or the public, enforcement is pursued through civil litigation and remedies. The literature documents cases of bodily harm or death caused by managerial decisions which could not be tried before criminal courts, because the offense was attributed to a corporation rather than an individual (Salinger, 2013, pp. 220–221). Civil procedure is used instead of criminal procedure. One potential defect of civil litigation is that it tends to frame harms in monetary terms, which may encourage companies to engage in cost–benefit analysis. This effect is strengthened by a broad reliance on settlements, which reduces the legal process to a negotiation of the amounts to be paid. Another drawback of civil law litigation is that injured parties need to initiate it and face heavily resourced corporate legal teams. In the case of financial misconduct, however, there exists an institution designated to represent the interests of the public by litigating civil cases.

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is an independent agency of the United States federal government created by the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to regulate the securities markets. It litigates offenses in cases of financial misconduct involving securities, a term defined in both the 1933 and 1934 Acts. The jurisdiction of the SEC covers a wide range of offenses such as insider trading, accounting fraud, market manipulation, misreporting by issuers of financial instruments, and corruption. The Commission can initiate civil or administrative actions when an infraction warrants it. Cases associated with SEC rules and regulations can be handled by SEC Administrative Law Judges. The Commission generally litigates offenses attributed to individuals in civil actions brought in Federal US District Courts. A parallel criminal action can also be brought by the US Department of Justice Attorneys, although this frequently leads to a delay in the civil action until the criminal case is adjudicated. Some cases against corporations are not brought in district courts but rather settled in SEC Administrative Proceedings.

The mission of the SEC, according to the agency’s website, is to protect investors, maintain fair, orderly and efficient markets, and facilitate capital formation. This mission is achieved through a range of activities: bringing civil enforcement action against violators of securities laws, adopting and administering rules and regulations, facilitating access to information about financial instruments, and educating investors. The litigation of financial crime is the domain of the SEC Division of Enforcement, which employs roughly 1300 staff, and consumes more of the SEC’s resources than any of its other divisions (US SEC, 2020a, 2020b). Enforcement activities of the SEC are well staffed and funded relative to other federal agencies. Resources available to the SEC have increased by half since the financial crisis of 2008, strengthening its ability to enforce financial market regulation (Kedia & Rajgopal, 2011).

Rationality in Illicit Projects

Financial misconduct can be construed as the result of a rational decision-making process for a number of reasons. First, illicit financial schemes usually require an organization to function. The theory of the firm, from Ronald Coase through Herbert Simon and Oliver Williamson to the present, holds that organizing business is a means for obtaining economic gains compared to individual activity or market-contracting, be it legal or not (Conner & Prahalad, 1996). Perhaps Simon (1997) makes the clearest argument that individuals can approach objective rationality when they form part of an organization, thus overcoming the constraints of bounded rationality. When creating organizations, individuals improve the setting in which they make decisions by establishing authority, enabling communication and knowledge sharing. Second, at the individual level, it has been argued that offenders respond to rational incentives (Becker, 1968; Ehrlich, 1972). Third, individuals employed in organizations that engage in illicit financial activities tend to be educated professionals, trained to make rational, evidence-based decisions (Egan et al., 2019) and respond to economic incentives (Meiseberg et al., 2017). They are not likely to be biased by their personal situation, such as destitute poverty that would leave crime as the only possibility for subsistence (Foley, 2011). One can safely assume that legal alternatives for earning an income would always be available to them.

Utilitarian rationality applied to finance, or illicit financial activities specifically, requires that the net present value (NPV) of an activity be positive (cf. Damodaran, 2012; Fernández, 2002; Fisher, 1930). A financial activity is deemed rational if the present value of the expected benefits is at least equal to (or preferably larger than) the present value of the expected outlay. In a classic investment decision setting, the benefits are the net profit the decision-maker expects to receive in each subsequent period, while the outlay is the initial investment. When both the outlays and benefits are spread over time, net present value calculations take the form of discounted cash flow calculations. This commonly used technique compares the present value of a stream of outlays with the present value of a stream of benefits. It is more appropriate when outlays may occur later in the course of the activity. The final product of both methods is a single amount, the net present value, which can be used in decision-making.

If the net present value or the present value of discounted cash flows of an activity is positive, a project is assessed as worthwhile in financial terms. Should a decision-maker consider a set of activities, rather than a single one, it would be rational for him or her to engage in all activities that beat the zero NPV threshold. Of course, a decision-maker faces resource constraints, which limit the number of projects one can engage in. Investment decision rules would suggest selecting a subset of projects which offers the largest positive sum of NPVs. A decision-maker can then attempt to sell the remaining projects to parties with the resources to execute them. Thus, in an ideal world of frictionless markets, all projects that beat the zero NPV threshold would be executed.

In sum, we can expect that illicit financial activities undertaken passed the NPV test. Hence, the decision to engage in them is rational ex ante. The three elements potential perpetrators need to consider when evaluating unlawful projects are: the stream of benefits, the stream of costs, and the discount rate to be applied. We apply these concepts to analyze a specific case of misconduct in Section IV.

The Benefits of Financial Misconduct

Financial misconduct benefits corporations and individuals in various ways, depending on the type of infraction. Traders and investment advisors can make profits by conducting transactions with parties who pay illicit fees, or by concluding trades at prices different from those communicated to clients. Investment companies can misappropriate funds collected from investors or withhold fees much greater than those permitted in contracts with them. They can also misinform investors regarding their performance to attract more clients (Egan et al., 2019). Corporations can increase their attractiveness by misstating accounting numbers so as to meet or beat analyst forecasts. Failing to report events that may affect the stock price negatively can help avoid problems in credit relationships. Managers may engage in fraudulent activities to exploit their incentive packages (Amiram et al., 2018).

The benefits of financial misconduct are typically spread over time, although the specific schedule depends on the type of illicit activity. To date there have been no studies, to the best of our knowledge, that would provide statistical evidence about these benefits. We resort, therefore, to presenting a selection of cases reported by the SEC in its litigation releases. Schemes that involve defrauding investors require time for the collection of funds and even more time for the transfer of benefits to perpetrators. For example, an investment company misreported the value of its portfolio, allowing it to obtain tens of millions more in funding than it would otherwise have secured (SEC Press Release, 2019, p. 166). The benefits in the form of additional funds accumulated over 18 months. In another case, a company offered ratings of blockchain instruments to investors without disclosing that it was collecting fees from the issuers of these instruments (SEC Press Release, 2019, p. 157). The benefits, in the form of unlawful fees, accrued each month. In contrast, accounting fraud typically aims to conceal negative information that may affect the stock price or business relationships. For example, a real estate company manipulated a performance measure so as to report that it had met its targets, when in fact it had not (SEC Press Release, 2019, p. 143). In another case, senior executives of an engine-manufacturing company misled their accounting personnel, leading them to inflate reported revenues by millions of dollars (SEC Press Release, 2019, p. 137). The benefits appeared before the discovery of the illicit action in the form of continued employment and pay despite incompetence.

The Costs of Financial Misconduct

The costs of financial infractions levied by the SEC include penalties and disgorgement of ill-gotten gains (Hall, 2009). Penalties are punitive in nature, while disgorgements are a form of restitution, an equitable remedy. However, the non-punitive nature of disgorgements was challenged as the SEC attempted to increase the amounts it sought in litigation. In Kokesh versus SEC the US Supreme Court (2017) raised a number of issues pointing to the punitive nature of disgorgements. First, disgorgements in SEC litigation result from harm to the public, not to any individual. Second, they need not be distributed to the harmed parties. Third, the amounts of disgorgements can be much larger than penalties, depending on the benefits that accrued to the perpetrators as a result of their crime. The median penalty in 2020 was about $200 thousand, while the median disgorgement ordered was about $500 thousand (US SEC, 2020a). The highest penalty ever, ordered to JPMorgan in 2013, was $200 million, while disgorgements can exceed a billion dollars (US SEC, 2019). The US Supreme Court ruled that disgorgements are punitive and therefore can only be applied within a five-year statute of limitations. Thus, Kokesh underscores the limits of using disgorgements as a deterrent to financial crime. In response to these developments, the US Congress defined money penalties sought by SEC as civil and explicitly authorized the SEC to seek disgorgements, setting the statute of limitations to 10 years for violations against provisions involving scienter and 5 years otherwise (National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021).

The SEC obtains orders for the payment of about $4 billion annually in disgorgements and penalties (US SEC, 2020a). Most of this amount is attributable to the top 5% of cases involving major Wall Street institutions and global firms. In addition, the Division of Enforcement obtains bars and suspensions on a few hundred individuals practicing finance. The division notes in its annual statement that “individual accountability is critical to an effective enforcement program”, and “experience teaches that individual accountability drives behavior and can also broadly impact corporate culture” (US SEC, 2020a, p. 8, 25). Cases brought against individuals typically involve small firms or small-scale violations, such as misreporting, but the SEC aims to pursue actions against top corporate officers. Large-scale crimes, in contrast, involve organizations where personal liability is not easily established (Ciepley, 2019).

Additional costs may occur in the form of damages resulting from civil actions brought to court by harmed parties. Civil actions are an alternative, private enforcement mechanism that can be employed in litigating financial misconduct. According to Choi and Pritchard (2016), who compare the effects of litigation by SEC with civil class actions, civil actions lead to greater stock-market effects and are more likely to force executives to stand down. Moreover, there are many cases for which class action is the only enforcement mechanism. The SEC selects which cases to pursue, while harmed investors typically face only one case which they can choose to pursue or not. For example, class actions are more likely than SEC litigation in cases of little public interest, in which few investors were harmed.

The direct costs of litigation are limited. Many individual investors lack the requisite knowledge and resources to pursue civil action, leading them to forgo opportunities for restitution. The US regulator recognized this problem in the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, which allowed the SEC to create and distribute civil fines collected in fair funds (Velikonja, 2015). The fair funds compensate investors in cases of customer fraud and other infractions committed by financial intermediaries who prey on the ignorance of individuals. However, this only takes place if the perpetrator is a large enough institution not to declare bankruptcy during litigation. Moreover, in some cases, litigation is not allowed. For instance, US corporate offenders are shielded from foreign litigants. Even in extreme cases, such as the Bhopal disaster in 1984, US courts refused to allow foreigners to seek civil remedies.

Companies incur the indirect costs of crime, although the evidence as to the severity of these costs is inconclusive. Indirect costs include damage to stock price (Choi & Pritchard, 2016; Flore et al., 2017), increased costs of financing (Arena, 2018; Gong et al., 2020; Nicholls, 2016), reduced leverage (Malm & Krolikowski, 2017), and reduced investment (Arena & Julio, 2015). The negative stock price reaction can be severe following the discovery of securities fraud, suggesting that investors punish companies for offenses against the market (Haslem et al., 2017). Once a settlement is concluded, however, the stock price recovers, even when a company formally admits wrongdoing (Flore et al., 2017). Overall, the literature provides a mixed picture of the indirect effects, which can vary from none to double the cost of litigation, or even ten times the cost of litigation. Karpoff et al. (2017) attribute the divergence of results to data collection issues. It is simply difficult to ensure that the data contains all the litigation events concerning a company, and that the details of each event are complete and correct.

Loss of reputation may be an important cost of misconduct, although the evidence is also inconsistent. Coffee (1981) considers sanctions that would affect reputation but concludes that they cannot be applied systematically. Haslem et al., (2017) argue that damage to reputation cannot be studied empirically unless it is separated from other effects of litigation, such as the increased probability of follow-up litigation, additional penalties and fees, or the financial distress brought about by sanctions. According to their study, much of the prior literature incorrectly measured reputation losses as all effects other than the direct cost of litigation. In their large sample study, they find no reliable indications of reputation losses following misconduct, with the exception of securities fraud.

Moreover, reputation may not be equally important to all companies. In fact, some companies appear to specialize in employing finance professionals with prior misconduct records (Egan et al., 2019). Banks with a track record of misconduct appear to attract clients who value prowess rather than integrity. During the recent financial crisis and its aftermath, press reports of misconduct by investment banks were positively correlated with higher fees and increased chances of participating in initial public offerings of companies in the US (Roulet, 2019).

Note that the aforementioned costs of crime are realized only if the crime is discovered, and perpetrators may be convinced this will not occur (Amiram et al., 2020). Indeed, several techniques for reducing the likelihood of discovery have been identified. Targeting individuals with lower levels of education, for example, decreases the chance the victims will notice they have been misled by financial advisors (Egan et al., 2019). Companies can choose to commit offenses in locations where authorities have fewer resources to pursue enforcement actions. Kedia and Rajgopal (2011) show that the distance to the SEC headquarters is associated with the probability companies will engage in account manipulation. Apparently, companies are aware that the longer the distance from headquarters, the lower the likelihood of enforcement actions. Fortunately, SEC offices are based in the main financial hubs of the East Coast and California, thus increasing the expected costs of committing crime in these locations. There are only 11 offices, however, indicating that the distance from the location of the offense to the nearest office may be thousands of miles. For instance, the San Francisco office covers the western states up to Montana, while the Denver office covers states from North Dakota, through Wyoming, down to New Mexico. Hawaii falls under the jurisdiction of the Los Angeles office. Indeed, Habib et al. (2018) find that money laundering, a specific type of financial crime, is systematically more common in some states than others. Interestingly, this leads auditors to demand higher fees from companies incorporated in these states, but crime rates continue to be high.

Organizations that engage in financial misconduct can avoid bearing the costs of crime, even once the crime is discovered and litigation begins. Small organizations can declare insolvency, or otherwise benefit from limited liability status. Large organizations, such as investment banks, can build legal teams and other resources that reduce expected costs or delay payments that can result from litigation. Such resources are effective because civil litigation generally takes the form of negotiations over the type of agreement and specific provisions. In cases litigated by federal authorities, deferred prosecution agreements and non-prosecution agreements move cases out of the courtroom and allow corporations to settle with authorities without admitting guilt (Flore et al., 2017). Companies can also reach more beneficial agreements by employing independent directors with strong social networks (Kuang & Lee, 2017). Further, systematic financial contributions to political action committees are effective in reducing the likelihood of SEC enforcement and the amounts of penalties (Correia, 2014), especially if the supported politician holds a seat on relevant congressional committees (Mehta & Zhao, 2020). These various methods for reducing the cost of enforcement are similarly effective in other countries, including China (Wu et al., 2016).

Finally, it should be noted that the amounts ordered may never be collected. According to the SEC financial statement for the year ending on September 30, 2020, as much as $1.2 billion of penalties or disgorgements were yet to be collected, but $1 billion of these were deemed uncollectable by the SEC staff, bringing net receivables down to roughly $0.2 billion (US SEC, 2020a, 2020b, p. 80). Payments can also be ordered by federal courts and paid directly to the courts, rather than to the SEC. It is unclear what proportion of these amounts is ever collected. The SEC does not provide information about collections on a case-by-case basis. One may assume that large corporations pay the sums stipulated in agreements with the SEC, while small corporations and individuals may avoid paying penalties due to lack of funds.

The Discount Rate on Financial Misconduct

The discount rate has a decisive effect on the results of NPV calculations and thus needs to be considered carefully. First, the higher the discount rate, the fewer the criminal activities that will surpass the threshold of zero NPV. As a result, fewer offenses are committed. Second, one can only observe the offenses committed, not those foregone. Since we take a rational perspective, we need to conclude that financial crimes are expected to be highly beneficial to perpetrators; otherwise, they would not be undertaken. Finally, a high discount rate causes the present value of potential litigation and enforcement costs to be reduced drastically with delay. Should the discount rate be equal to 30%, for example, the present value of any penalties or disgorgements to be paid in five years is only a fifth of the actual amount. Consequently, a high discount rate lowers the importance attached to costs in the decision-making process. Potential offenders only consider the spread of benefits over time and strongly prefer short-term projects.

The discount rate is defined in finance as the required rate of return (Fisher, 1930), framed similarly to bank interest. The rate is assumed as constant over time in the calculations of net present value for business projects. If a business uses the cost of capital framework for investment decisions, the rate would be the same for any project regardless of the level of risk. In contrast to the business setting, the literature provides ample evidence of wide variations in the discount rates applied by individuals (Warner & Pleeter, 2001). Research in the criminal setting shows that the discount rate varies with the probability of detection (Davis, 1988). Consequently, it is not feasible to apply a single discount rate to all decisions involving financial misconduct.

Economists are advised to adapt the discounting model to the specific domain they study, as no model appears to be universally validated (Frederick et al., 2002). We rely on the NPV approach used in financial decision-making, as the persons involved in financial crime are likely to have been trained in using this method.

One would assume the discount rate on crime to be higher than the discount rate applied to any legal activity in finance. Since organizations can engage in a variety of legal profit-making activities, we need to ask, why would they engage in financial crime instead? We can then attempt to estimate the discount rate on financial crime by referring to the rates of return on alternative, legal activities. A recent survey of discount rates used in equity markets serves as a useful benchmark (Fernández et al., 2017). Low-risk investments in the US equity market would involve a discount rate of 8%, while similar investments in China would require a 11% discount rate. Investments in large emerging countries would involve rates of about 15%, with rates of 20% to 30% being applied in high-risk countries. In light of the above, we provide results for discount rates ranging between 10 and 40%.

Illustrative Case

In this section, we investigate what net benefits a potential perpetrator of financial misconduct might expect to obtain. An organization or a person who considers engaging in misconduct would do well to take guidance from cases that are covered by the media, released by the SEC, or resolved by US courts. They provide insight into the workings of illicit schemes, the benefits and costs involved, and the time frame over which a scheme is organized and litigated. For illustration purposes, we select a highly visible case of a Main Street broker, Charles Kokesh, who was brought to court by the SEC, found liable for several infractions by a jury, and ordered to return ill-gotten gains to defrauded investors (Securities and Exchange Commission vs. Charles R. Kokesh, D.N.M. 2015). The case received much attention when the US Supreme Court reduced the amount to be returned by Kokesh and set new limits on disgorgements that would apply in subsequent SEC litigation (Kokesh vs. SEC, 581 U.S., 2017). We provide references to official documents available from US courts and the SEC to support case description.

Kokesh vs. SEC

Charles Kokesh is an investment adviser whom a jury found liable for converting nearly $35 million of funds invested in four business development companies to his own use (Securities and Exchange Commission vs. Charles R. Kokesh, D.N.M. 2015). According to the SEC Complaint, Kokesh exploited a common feature of the financial industry, viz., that the invested funds and the advisory company that manages them are both controlled by the same entity or person. Kokesh formed two investment advisory companies in 1987: TFL and TFI. The former company was registered in El Dorado Hills, California, and the latter in Santa Fe, New Mexico, as a Delaware corporation. Both companies registered as investment advisory services with the SEC were controlled by Kokesh. He also controlled four closed-end investment companies, which were advised by TFL and TFI. These companies chose to be regulated as business development companies (under the Investment Company Act of 1940) and registered a class of securities with the SEC. Their objective was to sell the securities and collect proceeds from individual investors for the purpose of investing them in small companies. Kokesh offered clients the possibility of benefiting from venture capital opportunities. He raised roughly $128 million from 21,000 investors, with average investment totaling $6,000 (Complaint, Securities and Exchange Commission vs. Charles R. Kokesh, Docket No. 6:09-cv-1021 SMV/LAM, Document No. 1, Filed Oct. 27, D.N.M. 2009).

The SEC charged in its complaint that the scheme—begun in 1995 and involving fees collected from the investment companies by the advisory firms, TFL and TFI—generated fees far in excess of those stipulated in the advisory agreements, and reimbursements prohibited by these same agreements (Complaint, p. 1). For example, the companies allegedly paid as much as $6 million in illegal distributions to Kokesh in 2000 alone (Complaint, p. 6). Bonuses were paid to Kokesh and other individuals charged from the assets of the investment companies, directly. In order to conceal the scheme, the companies controlled by Kokesh filed fraudulent proxy statements and reports (e.g., 10-Qs and 10-Ks) with the SEC (Complaint, p. 8). The fraudulent filings were carried forward, rendering subsequent filings equally fraudulent. Kokesh continued his activities until 2006. Altogether, the SEC assessed that the scheme generated $45 million in net benefits to Kokesh. Eventually, a jury verdict reduced this amount to $35 million.

The case was adjudicated over a number of years. The SEC filed its complaint in 2009, seeking a permanent injunction, disgorgement of the benefits illegally obtained, prejudgment interest, and civil monetary penalties. Following a trial in 2014, the jury found Kokesh liable for converting funds to his own use in violation of the Investment Company Act of 1940, aiding and abetting in the organization of a fraudulent scheme in violation of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, and misreporting to the SEC in violation of the Exchange Act of 1934. In 2015, the court entered the final judgement ordering Kokesh to pay a civil penalty of $2 million, to disgorge $35 million of ill-gotten gains, and to pay $18 million of prejudgment interest (Memorandum Opinion and Order, Docket No. 1:09-cv-1021 SMV/LAM, Document No. 184, Filed March 30, D.N.M., 2015). The total order amounted to $55 million. The court also ordered an injunction, enabling the SEC to commence administrative proceedings and issue a bar order (SEC, 2015).

The case did not end there, however, as Kokesh contested the amount of disgorgement before the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit and, finally, before the Supreme Court of the United States. His lawyers argued that the disgorgement was punitive in nature and thus subject to a five-year statute of limitations. This would limit the time over which the disgorgement amount was calculated to the period between 2002 and 2006, rather than the initial period between 1995 and 2006 considered by the SEC. Fraudulent gains captured prior to 2002 would fall beyond the statutory limit and, hence, be unreachable. The fraud’s most lucrative early years would thus be safe from recovery. In 2017, the Supreme Court ruled in his favor in Kokesh vs. SEC (581 U.S., 2017). In 2018, the Court of Appeals consequently reversed the judgement of the district court and remanded, with instructions to order a disgorgement of $5 million plus prejudgment interest of $3 million, instead of the initial $35 million plus $18 million of prejudgment interest (Docket No. 0:15-2087, 10th Cir. 2018).

While direct litigation costs are much lower than the benefits Kokesh obtained, he suffered material indirect costs. The SEC banned him from practicing his profession, potentially crippling his future ability to earn an income. The litigation itself took over a decade, a period during which his ability to earn a living was also impaired by the associated publicity. His very name is invoked each and every time the Supreme Court’s ruling is discussed. On the other hand, the literature reviewed in the preceding section suggests that his skill set would be valued in gray areas of the financial markets, indicating that he might be able to find employment there. There is certainly no suggestion that Charles Kokesh will undertake any such activities in the future.

Case Analysis

One can learn much from the case about just how profitable it might be to organize a similar scheme. Following the experiential guidance provided by this widely known and broadly discussed case, a potential perpetrator would plan on controlling both the investment advisory companies and the business development companies, a key feature of the scheme. The investment advisory companies would make outlays for the creation of the business development companies and the marketing of investment products to retail customers. These initial investments would likely be recoverable from legally obtained proceeds. Once the companies accumulated a sizable amount in client amounts—say, $100 million—a perpetrator would be able to begin converting the funds to his own use without risking immediate discovery. It would only be after many years that the total amount of converted funds would become large enough for clients to notice.

The NPV of the scheme would be based on expectations regarding the flow of benefits and costs over time, including litigation costs resulting from the scheme being discovered. The case illustrates that payments in violation of the contractual amounts can be diverted continuously for as long as a decade in the form of salaries and bonuses. Funds in violation of contractual amounts might also be diverted to reimburse the expenses of other operations, such as rent. Given the scale of this operation, one could expect benefits to reach $3.5 million per year and to accumulate for a decade. Assuming that the scheme was discovered, as it was in Kokesh’s case, a court might order the perpetrator to return the nominal value of the gains. Following the Supreme Court’s statute-of-limitations ruling, however, it can only order the return of the gains obtained over the most recent five-year period. Moreover, court proceedings are time-consuming, and sentencing could easily be delayed by filing appeals. For instance, Kokesh’s final judgement was entered in 2015, nearly a decade after the scheme ended. The Supreme Court’s adjudication delayed the final order by another three years.

Figure 1 shows the present value of such a scheme as a function of the discount rate. The calculation assumes an annual net benefit of $3.5 million accumulated over the period of a decade, a 14-year delay in litigation followed by a court order to return the benefits accumulated over the preceding 5 years amounting to $17.5 million, plus pre-judgement interest of $10.5 million. The dollar cost of litigation (not including legal fees and sundry expenses) could plausibly be expected to amount to $28 million. Under these assumptions, the project nevertheless appears highly profitable at any reasonable level of the discount rate. The present value of the benefits ranges from $22 million for a discount rate of 10% to $8 million for a discount rate of 40%. What is most striking, however, is the negligible cost in every scenario because of the decade-long delay in litigation and the five-year limitation on disgorgements. Even at the lowest discount rate, the present value of the litigation costs is a mere $3 million. Consequently, the scheme obtains a positive NPV of $19 million at the 10% discount rate.

Discussion

Neoclassical economic theory is built upon the notion of utility as the driving force in the choices of individual consumers and workers. Thus, rationality is defined as the ability to maximize utility. Edgeworth (1881, p. 16) claimed that “the first principle of Economics is that every agent is actuated only by self-interest.” Although he corrected himself later, saying it would be better to consider humans as impure egoists or mixed utilitarians, this perspective has persisted in economic and psychological models. The influence of utilitarianism goes beyond economics to law and ethics (McGee, 2009; Yunker, 1986). Becker’s (1968) theory of subjective expected utility (SEU) describes criminals as rational utility maximizers in conditions of risk. Accordingly, he analyzed the amount of resources and punishment needed to enforce legislation. Regulators should determine how many offenses can be permitted and which offenders may go unpunished for the greater good (Becker & Stigler, 1974). However, some economists suggest that the neoclassical approach only considers the impact of external interventions on behavior and ignores the intrinsic motivation of economic actors (Frey, 1997). In social and developmental psychology other types of motivation, apart from utility, have also been analyzed (Bolino & Grant, 2016; Carlo, 2014; Penner et al., 2005; Wuthnow, 1993).

Psychology offers a richer understanding of human behavior by acknowledging other motivations besides the extrinsic or utilitarian. Woodworth (1918, p. 70) was probably the first to distinguish between activities “driven by some extrinsic motives” and those “running by their own drives” (intrinsic). Half a century later, de Charms (1968) followed through by differentiating the “locus of causality” among actors: those who have the “locus of causality” external to them are extrinsically motivated, while those who find it within themselves are intrinsically motivated. More recent scholars speak of extrinsic motivation “whenever an activity is done in order to attain a separable outcome” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 60) or when work is carried out to obtain external outcomes, such as rewards or recognition (Amabile, 1993; Amabile et al., 1994; Brief & Aldag, 1977). By contrast, intrinsic motivation occurs when an activity is desired for its own sake, when it is performed for some inherent satisfaction, such as the fun or challenge it entails (Locke & Schattke, 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2000). People are intrinsically motivated “when they seek enjoyment, interest, satisfaction of curiosity, self-expression, or personal challenge in work” (Amabile, 1993, p. 186), showing competence and task involvement (Amabile et al., 1994). They engage in behaviors even in the absence of reward or control (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Furthermore, besides extrinsic and intrinsic motivations, there is a third type, called “altruistic motivation,” which has been studied since the late 1970s. Altruistic motivation is the desire to benefit others or to expend effort out of a concern for them (Batson, 1987), to protect or enhance their welfare (Schwartz & Bilsky, 1990). Examples of altruistic motivation at work would be seeking the welfare of one’s family, wanting to “make a positive impact” on society, truly looking out for the benefit of clients, and so forth. Altruistic behaviors include acts of helpfulness, charity, self-sacrifice, and courage, out of concern for others, without seeking rewards (Monroe, 1996, 2002; Rosenhan, 1972). Other scholars use the terms “transitive” or “transcendent” to designate altruistic motivation (Caprara et al., 2005; Grant, 2008; Guillén et al., 2015; Penner et al., 2005; Perez Lopez 2014; Torres, 2001). In extrinsic and intrinsic motivations, the agent is self-centered, looking for social or material rewards (money, recognition, prestige, and so forth) or the enjoyment of an activity or personal achievement. In altruistic motivation the main purpose of action is the welfare of others (although secondary motivations are also admissible).

Utilitarian rationality and extrinsic motivation are transposed into the realm of financial investing in the following manner: An action is deemed rational if and only if its resulting net present value is greater than zero. Actors are extrinsically motivated in their behaviors by separable monetary rewards or outcomes exclusively, not by any values intrinsic to their performance. Correspondingly, an expected net present value less than zero would be considered irrational; it would not be motivating. A net present value of exactly zero indicates an exact balance of benefits and costs, implying indifference. Deterrence efforts by regulators and authorities, presumably, should endeavor to reduce the net present value of financial misconduct and fraud to below zero by increasing their costs in the form of monetary penalties and other sanctions to individuals and organizations. Extrinsically motivated actors refrain or curb their behaviors in response to external controls or punishments alone.

As suggested by the illustrative case and the terms of the foregoing rationale, a reliance on legal action directed primarily towards securing monetary penalties and other extrinsic sanctions is insufficient to obtain the predicted outcome. For an individual broker it is profitable to convert the funds invested by clients and file false statements over many years. Even if such a scheme is discovered and successfully prosecuted, the statute of limitations curtailed by the Supreme Court assures a positive NPV. Expected benefits outweigh the costs, making a choice to engage in misconduct “rational” in accordance with a standard utilitarian perspective. Thus, if financial activities are seen to be driven exclusively by the extrinsic motivation of monetary gains or external rewards, misconduct is unavoidable.

An inference and a question follow from the above. The inference is that, under the US regime, the costs of illegal financial activity, calculated in direct (fines, penalties, disgorgements, and so forth) and indirect (reputational, insofar as it affects stock price and profits) losses, do not outweigh economic benefits to organizations and individuals. Therefore, deterrence measures alone are ineffective given the terms of the subjective expected-utility approach. The extrinsic motivation of increased wealth sustains financial misconduct. Due to a positive expected NPV, it remains rational to engage in financial fraud and misconduct.

The question is why more people and organizations do not engage in illicit financial activities, given how profitable they are. Let us leave aside the instances of financial malfeasance which are neither discovered nor prosecuted. Given the favorable odds, why is not everyone committing financial misconduct, since it is supposedly the rational and profitable thing to do? Egan et al., (2019) find an incidence rate of 7.3% among financial brokers, half of which is attributed to settled disputes, leaving some 3.6% for illicit activities. The rate drops to 1%, if one considers the entire industry (Parsons et al., 2018). The vast majority of agents appear to be behaving honestly and honoring their fiduciary commitments. They do not actually behave as the simple utilitarian model predicts. There ought to be other models of rationality, therefore, that are not based on utilitarian premises. We have already seen how the utilitarian, neoclassical economic framework aligns with extrinsic motivation, insofar as external rewards and controls explain financial behaviors. This model of rationality can be depicted as egoistic as well, because of the focus on the actors’ own benefits and harms. Accordingly, other motivations beyond the extrinsic ought to be employed in describing the behavior of financial actors.

Our contention is that, given the inadequacy of utilitarian thinking and extrinsic motivation to explain actual financial behavior, we need to consider intrinsic motivation and altruistic motivation as well. Economists have gathered empirical evidence of motivations other than self-interest and external rewards (Fehr & Schmidt, 2006; Frey, 1997). Altruism, fairness, and reciprocity have been considered as strong motivators, apart from self-interest. Although psychologists held at first that motivation for all intentional action is egoistic, in the past thirty years researchers have gathered support for altruistic motivations (Batson & Shaw, 1991; Penner et al., 2005). Not only do utility and extrinsic motivation fail to deter financial misconduct, but they are also insufficient to explain and predict the full range of actual financial decision-making. For this, recourse to intrinsic and altruistic motivations is necessary.

Financial organizations would do well, then, to acknowledge that, besides external economic utilities, actors take intrinsic motivation and altruistic motivation into account in their decision-making processes. These represent goals which are not externally separable and egoistic: in the case of intrinsic motivation, an improvement in a professional skill or ability, or the enjoyment of a task or job (Kanfer et al., 2017); in the case of altruistic motivation, the direct welfare of others. Naturally, given the social nature of agents, one may at the same time benefit others indirectly and secondarily.

The different types of motivation affect not only the agents’ decision-making processes, but also their organizations. Many studies have confirmed the organizational benefits of intrinsic motivations (Cho & Perry, 2012) and altruistic motivations (Bolino & Grant, 2016; Thompson & Bunderson, 2003). Intrinsic motivation generates a sense of autonomy and competence (Deci & Ryan, 2000). It partially mediates the psychological empowerment-work performance relationship, and promotes a positive relation to research and development, contextual and innovation performance (Li et al., 2015). Altruistic motivation enhances well-being and performance, productivity, and persistence (Bolino & Grant, 2016; Thompson & Bunderson, 2003). It creates ripple effects in organizations, increasing job satisfaction and making teams more successful (Aknin et al., 2011). It predicts higher profitability, productivity, efficiency, and customer satisfaction, as well as lower costs and lower turnover rates (Podsakoff et al., 2009).

When applying this alternative model of rationality, it is important to note that different kinds of motivations can enter into play simultaneously (Schmidtz, 1993). For instance, financial actors could be motivated to provide excellent service (altruistic), while seeking to earn money for themselves (extrinsic motivation) and improve job-related skills (intrinsic motivation). It is worthwhile to consider the interactions among extrinsic, intrinsic, and altruistic motivations. The interaction most studied until now is the one between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, also called the “crowding in /crowding out” effect (Staw, 1974). Despite situational variance, it seems that adding extrinsic rewards corrupts natural intrinsic motivations (Deci, 1975; Frey, 1997). Once again, the utilitarian, neoclassical economic approach of the self-interested and extrinsically motivated actor offers a very limited account of actual behaviors.

Besides the motivational aspect of the agents, the impact of financial activities on the moral excellence or virtues of the actors themselves, especially insofar as these are constitutive of the flourishing they seek as a common end-goal, is also worth considering (Grant et al., 2018; Sison et al., 2019). Unlike motivations, largely limited to providing explanations of particular behaviors, virtues carry out descriptive and especially normative or evaluative functions of the actors themselves (Alzola, 2012, 2015). Virtues present a fuller picture of actors’ mental states (beliefs, desires, and emotions), more enduring explanations of conduct through stable character traits, and a reflection of value systems made firm through deliberate choices. Moreover, virtues are a necessary condition and partially constitutive of flourishing (Hursthouse, 1999). In the neo-Aristotelian version, flourishing encompasses utility (external, instrumental, and material goods such as wealth) and intrinsic (self-regarding) as well as altruistic (other-regarding) motivations. How, one might ask? The answer is through a hierarchical ordering, which actors establish by exercising the virtues. The challenge then becomes how to exercise the virtues in financial activities and business dealings in general. To the extent they are successfully exercised, not only will financial crimes and all sorts of misconduct be avoided, but the financial professionals themselves will also come closer to achieving flourishing while excelling in finance.

How does virtue ethics view utility, and by extension, extrinsic motivations such as wealth, outcomes separable from economic actors? They are seen as goods, not only as objects of desire, but as things that perfect the agents, satisfying their needs (Sison et al., 2019). However, they are conceived as instrumental goods, desirable not in themselves but insofar as they lead to other goods, and eventually, to other goods desirable in themselves (and ultimately, to flourishing). There is nothing wrong in seeking profits or positive NPV in financial and business dealings, as that provides the means necessary to satisfy basic needs (food, clothing, housing) and others (health, education, leisure, and so forth) in a market economy. Among the goods material wealth obtains, some continue to be instrumental (food for sustenance), while others are goods in themselves (leisure).

Problems arise when we turn instrumental goods, such as wealth, into goods in themselves, mistakenly pursuing them in this manner. Also known as improper chrematistics, money or wealth is accumulated for its own sake, effectively converting it into an end instead of a means to acquire other goods (Rocchi, 2020). This would occur when we choose material wealth or NPV as an absolute end, regardless of anything else. Then we would not hesitate to mislead our clients about the pricing of trades or the use of their funds; neither would we have scruples about filing false reports with regulatory agencies or otherwise deceiving the SEC. The only thing that matters then would be to increase the financial return on transactions. Moreover, we would then fail to recognize any limit to the amount of material wealth propitious to flourishing, we would deduce that more is necessarily better and that we should accumulate as much as possible. This unrestrained pursuit of profits alone also often entails succumbing to an extremely short-term horizon or vision of success in finance (Van de Ven, 2011; Wyma, 2015). In virtue ethics, this would be giving in to the vice of greed or avarice, whose opposite virtue, moderation, establishes that there is a certain level past which wealth no longer contributes to flourishing but detracts from it (Rocchi et al., 2020).

Although it might be the intent of punitive measures (e.g., jail time, fines, sanctions) to counteract the unbounded desire for wealth and profits, we not only have reason to doubt their effectiveness (in light of the illustrative case cited above), but also to suspect that by falling prey to the same assumption (more is good, less is bad), exclusive reliance on them might contribute to the very problem they seek to fix. It could even be argued that given the incentive structure in a capitalistic system, these financial actors were simply doing what they were supposed to according to their roles, and thus, without fault (Van de Ven, 2011). Having given in to falsehood and an unbridled desire for wealth, agents no longer balk at committing injustice, short-changing business partners, or engaging in craftiness, even seeking ways and means to hide wrongdoing. This same cunning is employed to make use of legal loopholes such as statutes of limitations, settlements, and so forth to wring out the best deal for oneself financially, without admitting guilt or expressing remorse. Thus, virtue ethics shows how instrumental goods (or extrinsic motivations) such as wealth and profits can be corrupted, with agents falling into opposite vices.

Virtue ethics enriches the understanding of the extrinsic, intrinsic or altruistically motivated agent’s impact on her- or himself and on others, by proposing the ultimate goal of flourishing as a common good (Sison et al., 2019). Virtues as personal moral excellences constitutive of flourishing effectively combine intrinsic and altruistic motivations. As we have seen, some approaches only consider the existence of actors’ self-interested motivations. This is part of the liberal, post-Enlightenment legacy which views human beings essentially as individuals, capable of independent existence and agency (anthropological and methodological individualism), whose interactions are governed by quasi-mechanical laws, not very different from those of physics (MacIntyre, 1998). Thus the attempt in economics, business, and most social sciences to quantify human behavior and “discover” inexorable laws that predict behavior: for instance, the belief that rationality consists in maximizing individual utility, in whatever form. In MacIntyre (1999), such individualism is closely linked to bureaucratic compartmentalization, the separation of human existence into independent life-spheres, each with its own set of rules and values. As a result, human life becomes fragmented, issuing in a loss of an overarching moral agency and responsibility.

By contrast, given its pre-Enlightenment roots, virtue ethics subscribes to a personalist view of human beings: people are always, simultaneously, and on equal counts, individuals and relational or social beings (Sison & Fontrodona, 2012; Sison et al., 2019). Evidence for this may be found in biology (sexual reproduction), developmental psychology (the extended need for nurturing of children by parents within families to reach mature human status), and politics (humans as linguistic animals who use language and abstract thought to organize themselves into complex communities) (Kass, 1999). Similarly, MacIntyre (2007 [1981]) insists that human identity and final end (telos) are socially determined by our belonging to a variety of groups, not necessarily of our own choosing, which situates our existence in a web of reciprocal duties and obligations. Human beings are not originally individuals who only later choose to enter into social relationships to pursue self-interest. Rather, they are persons born into families who can achieve their ultimate goal of flourishing only within a political community and as a common good. Their flourishing, telos or final end is never achieved in a universal, abstract way, but always in a socially, historically, and culturally embedded manner.

A common good is one that can be achieved only insofar as everyone else in the community achieves it; it is not divided and distributed, but shared and participated in (Sison & Fontrodona, 2012). A common good is an object of cooperation, not competition; it is not zero-sum, nor merely Pareto optimal distribution. Because human beings are personal, their ultimate goal of flourishing in political communities can be reached only if each member reaches it as well (MacIntyre, 2016). In the liberal, individualistic mindset, virtues are at best only a means to attain each one’s version of the good life, understood as the satisfaction of individual preferences, whatever these may be. But for MacIntyre (2007 [1981]), virtues themselves are constitutive of flourishing, and true flourishing is one necessarily shared amongst all members of society. This understanding of flourishing sheds new light on the conceptual dichotomy between self-interested and other-interested motivations because among persons, there can be no strictly individual interest without repercussions on others; and conversely, there can be no purely social interest that does not affect one’s own. Given the personal nature of human beings, intrinsic motivations have a positive impact in others. The same holds true for extrinsic motivations. This does not deny the possibility of egoism or selfishness; rather, it shows why such behavior is an anthropological misconception that augurs moral failure.

How do financial activities, and excellence in them, contribute to the common good of flourishing (Grant et al., 2018; Sison et al., 2019)? Flourishing requires two kinds of goods: external, material goods, and internal, non-material ones (Nicomachean Ethics 1099a, The Politics 1323b–1324a). External, material goods lie within the purview of the economy, of which finance forms part (The Politics 1253b). Finance as a form of “wealth-getting” or chrematistics (The Politics 1253b) represents the efforts, through proper investments or resource-allocation, to obtain the material goods or “returns” whose consumption forms part of the good life. But which financial activities, how, and in which measure? For all of these questions we need the virtues: an element of the internal, non-material goods we develop in ethics. The virtues enable us to respond appropriately to these questions. For instance, studiousness and diligence allow us to discover creative and productive investment activities; obedience ensures conformity with the law; truthfulness helps to gain trust among clients; justice encourages fair market competition; moderation curbs inordinate desires for instant wealth and promotes sustainable, long-term profits; and practical wisdom guarantees that we choose to do the right thing at the right time for the right reasons. Therefore, excellence in financial activities through the practice of the virtues affords us the material goods whose consumption leads to our common flourishing.

A MacIntyrean version of the neo-Aristotelian account of the virtues would pose further requirements. Above all, it would have to overcome MacIntyre’s explicit critique of finance (MacIntyre, 2015), “business ethics” (MacIntyre, 1977), and institutions of capitalism (MacIntyre, 1995 [1953]) as realms hostile to virtue. Only then could it put forward an understanding of financial activity as a “practice” with its own internal goods and standards of performance excellence supported by institutions (Moore, 2012), explain how the goods of such a practice may be sought by individuals navigating through multiple, often conflicting roles in their personal narratives or biographies (Robson, 2015), and demonstrate how both the goods of practice and the goods of individual practitioners contribute to the common good of flourishing of their communities embedded in their own traditions (MacIntyre, 1994, 2007 [1981]). Each of these steps are fraught with problems. Different authors have different accounts of how finance qualifies as a MacIntyrean “practice” (Sison et al., 2019; Van de Ven, 2011; Wyma, 2015) or “domain-relative practice” (Rocchi et al., 2020). Likewise, there are several narratives of how financial actors pursue professional excellence through a variety of seemingly incompatible duties and obligations (Roncella & Ferrero, 2020), and how their efforts further not only their practice and professions but also community flourishing (Sison et al., 2018). Examining these issues in detail and drawing inferences and policy recommendations for financial crime deterrence is beyond the scope of this paper and constitutes directions for future study.

Implications for Policy-Makers and Managers

Let us now turn to the ways in which intrinsic and altruistic motivations, on the one hand, and virtue ethics, on the other, may contribute to better financial behavior than just fines and sanctions. How does the consideration of other types of motivations besides extrinsic, egoistic utility affect the regulation of financial conduct?

Among the generic remedies for corruption are increased monitoring, higher wages, and less discretion (Becker & Stigler, 1974; Kwon, 2012). According to some studies, extrinsic motivation, in the form of higher wages, for instance, leads to less corruption, but strong intrinsic and altruistic motivation can also boost ethical behavior. Bureaucrats with a strong public-service motivation, which includes attraction to public policymaking, commitment to the public interest, civic duty, social justice, self-sacrifice, and compassion possess stricter standards against corruption (Bolino & Grant, 2016; Perry, 1996). It seems that with higher wages as extrinsic motivation, one can “bribe” workers to observe a certain level of compliance, but intrinsically motivated workers have superior integrity. That is, they do not need to be bribed to be good.

Work motivation is of critical importance to public policymakers and organizations, given the repercussions on work environments, human resource policies, individual well-being and organizational success (Kanfer et al., 2017). However, the current focus of regulation is mainly on punitive economic sanctions in response to extrinsically motivated financial misconduct. We believe financial misconduct can be more effectively deterred by introducing and reinforcing intrinsic and altruistic motivations within organizations, through a leadership style and an organizational culture that promotes them. These interventions would not be merely reactive to misconduct, but proactive and preventive as a result. They would foster an alignment of goals of better performance, well-being, and long-term success between financial regulators and agents instead of the conflicts brought about by external rewards or profits.

Our claim that disutility, a negative extrinsic motivation, is insufficient to prevent financial misconduct in individuals and firms is supported and reinforced by the observation that there appears to be no single effective method for the deterrence of financial misconduct. Schell-Busey et al. (2016) focus on formal, legal, and administrative prevention and control strategies to deter corporate misbehavior in the US. In their meta-analysis of deterrence measures they find strongest evidence in favor of a mixed approach that includes law, punitive sanctions, and regulatory policy, all of which are examples of extrinsic motivation. Law and punitive sanctions refer to threats or the imposition of fines, prosecution, conviction, and imprisonment. Their effects on company or individual deterrence are inconclusive. Similarly, regulatory policy by itself, which comprises inspections and monitoring, yields mixed results on deterrence. Only a combination of these methods consistently produces a significant deterrent effect on corporate misconduct. Their tentative conclusion does not inspire confidence. Not only do extrinsic deterrents fail the test of NPV, as we have shown, but their composition and mix are apparently indeterminate.

We do not claim that utility or profit considerations are irrelevant or can safely be ignored. After all, a commitment to ethical behavior is correlated with superior corporate financial performance (Verschoor, 1998). We contend rather that in order to explain and predict the actual behavior of financial actors, other motivational factors must be taken into account. Consequently, the adoption of alternative methods of deterring financial malfeasance is likely to reinforce the actual bulwarks against it and improve results: e.g., educational efforts aimed at broadening the scope of financiers’ considerations, aims, and motivations. The main problem with focusing predominantly on utility or extrinsic motivation is that it reinforces an egoistic model of thinking in which agents seek their financial gain above everything else. Thus, it confirms financial actors in the very attitudes that prove inadequate to explain and predict their behavior. In a word, it is unrealistic. In the extrinsic deterrence model, whatever regard financial actors may have for others is subordinated to their own welfare, as if they really do not care about the consequences of their decisions and actions on others. Minimally, that flies in the face of evidence supporting acknowledgment of the effects that altruistic motivations exert on actual behavior. The challenge is to acknowledge and promote the development of motivations other than mere economic benefit for oneself. This implies designing deterrence strategies that promote intrinsic and altruistic motivations.

What further contributions can we expect from virtue ethics? Remember the prime objective of virtue ethics is to promote human excellence and flourishing; efforts to prevent misconduct are just means to this end (Sison et al., 2019; Sison & Fontrodona, 2012). Pursuing virtues insofar as they are constitutive of flourishing in effect combines intrinsic with prosocial motivations. While motivations have been the object of numerous empirical studies in conformity with modern scientific standards and the virtues have rarely, if at all, been convincingly measured, nonetheless they possess certain advantages. Not only do virtues provide explanations of the purposes of behaviors, but they also fulfil descriptive functions of mental states and express normative or evaluative judgments of the actors themselves. Further, recall that virtue ethics is not opposed to external material goods, wealth, or extrinsic motivation; it only requires they be kept in their proper place as instrumental goods. Nor is virtue ethics contrary to punitive laws and regulations; their necessity is acknowledged in the form of “exceptionless prohibitions.” Virtue ethics is distinctive in advocating a three-pronged approach that includes laws, an account of goods, and instruction in the virtues to achieve its goal.

What does this mean for finance? First, accommodate all legitimate laws and regulations, recognizing, however, that they represent just a third of the solution. At their core would be the “exceptionless prohibitions”: regardless of intentions or circumstances, it is never permissible to lie or state the contrary of what one knows to be the truth in regulatory filings, for instance. Second, provide an account of the goods finance is supposed to deliver. These are external, material goods in the form of financial resources that are instrumental in nature. They are not goods in themselves that ought to be pursued at all costs. There is a limit beyond which they no longer help, but instead hinder flourishing. Moderation, among other virtues, helps one realize where this limit lies. In any case, external material goods such as wealth should always be subordinated to internal, non-material goods such as the virtues, with both put at the service of the common good of flourishing in society. From a MacIntyrean perspective, the goods to be pursued with the virtues are actually three-fold: the goods internal to financial “practices” (sustained by the external goods of “institutions”), the goods embedded in the individual lives of financial practitioners, and the goods that financial practices and practitioners contribute to the shared flourishing of their communities. And third, emphasize training in the virtues through character formation; this is the crucial factor. Virtues are essentially good habits that develop through repetition. Just like mental habits (speaking a language) and mechanical habits (driving), we can acquire the moral habits or virtues through instruction, the presentation of role models, and personal commitment and practice. Perhaps the educational function of the SEC could be broadened to cover not only the technical, but also the ethical, virtue-focused aspects. Certification in this area could be required as well as taking a professional oath, just as lawyers and doctors do. And to help nudge finance professionals toward virtuous practice, we could make use of tricks already learned in psychology regarding motivations. For example, something similar to the Federal Corporate Sentencing Guidelines could be enacted for financial regulation, creating incentives for providing ethical training among professionals in the sector (Palmer & Zakhem, 2001). Thus, we see how rules or laws, goods or motivations, and the virtues come together in the quest to push financial practice toward professional and moral excellence as well as flourishing.

Conclusions

This paper provides evidence to establish that on an NPV basis, crime pays. After inquiring as to why more financial actors do not engage in financial impropriety given that it is presumably “rational” under prevailing assumptions, it sketches alternative methods of deterring financial misconduct, given that crime pays. It examines the utilitarian and egoistic rationality embedded not only in the neoclassical economic account of financial behavior, but also in the legal and ethical measures employed to prevent misconduct. It draws the parallel between economic utility and extrinsic motivation in psychology. By way of a representative case, we show that regulatory measures depending exclusively on utility considerations and extrinsic motivations are ineffective on those terms. Under the current US regime, the NPV of illicit financial dealings can be positive and therefore deemed an example of rational conduct.

The fact that the US financial system perdures attests, however, that not everyone is behaving as this model of rationality describes; they are not taking advantage of an unfailingly favorable calculus. This leads us to think there is a need for change in the framework underlying the regulatory regime that could better explain actual financial behavior and better shape future deterrence efforts. We consider two options: the first, founded on the motivational approach, and the second, on virtue theory.

The motivational approach suggests there are other motivations at work besides utility or self-interest and indicates that intrinsic motivation and altruistic motivation may be operative in the economic and financial behavior of both individuals and organizations. Intrinsically motivated and altruistically motivated financial actors are unlikely to engage in misconduct.

Second, we examine virtue ethics insofar as it provides not only an explanation of behavior, as motivations do, but a descriptive and a normative account of agents as well. Further, the virtues link individual conduct to both personal moral excellence and the quest for the common good of flourishing within communities. Thus, the virtues combine intrinsic and altruistic motivations. Virtue ethics underscores the instrumental value of financial wealth in respect of the final end of flourishing. MacIntyrean virtue ethics, in particular, requires that financial activities constitute “practices”, that that these “practices” be embedded in the individual lives of practitioners who fulfil complex roles, and that “practices” and “practitioners” be embodied in the traditions of communities, contributing to their shared flourishing. A detailed explanation of these stages and their incidence on specific deterrence efforts, however, would merit a separate study of its own.

From the above we draw at least three conclusions.

The first conclusion concerns the very limited effectiveness of deterrence measures based exclusively on utility and extrinsic motivation, as the neoclassical economic theory and its extension into law and ethics dictates. In the current US regime, there are instances in which the NPV of illicit financial activities are overwhelmingly positive. It may also be the case that workers, through high wages, are in fact “bribed” into behaviors compliant with the law. But that cannot be a definitive or long-lasting solution, because the stakes can always be raised.