Abstract

Applications of sexual selection theory to humans lead us to expect that because of mammalian sex differences in obligate parental investment there will be gender differences in fitness variances, and males will benefit more than females from multiple mates. Recent theoretical work in behavioral ecology suggests reality is more complex. In this paper, focused on humans, predictions are derived from conventional parental investment theory regarding expected outcomes associated with serial monogamy and are tested with new data from a postreproductive cohort of men and women in a primarily horticultural population in western Tanzania (Pimbwe). Several predictions derived from the view that serial monogamy is a reproductive strategy from which males benefit are not supported. Furthermore, Pimbwe women are the primary beneficiaries of multiple marriages. The implications for applications of sexual selection theory to humans are discussed, in particular the fact that in some populations women lead sexual and reproductive lives that are very different from those derived from a simple Bateman-Trivers model.

Similar content being viewed by others

In other species polyandry takes one of two forms: a female may desert her first mate for a second, leaving the first to care for their mutual offspring (serial polyandry), or she may have several mates at one time (simultaneous or cooperative polyandry). In humans, we don’t have a name for the former behavior and we don’t even bother to study it. Perhaps we should (Mealey 2000:323).

When a man and a woman each have a single spouse we call it monogamy. When a man is concurrently married to two or more women we call it polygyny, and when a woman is concurrently married to two or more men we call it polyandry. When men marry women sequentially, or women marry men sequentially, we call it serial monogamy.

Serial monogamy is almost always viewed as favorable to male fitness and unfavorable to women’s fitness (e.g., Forsberg and Tullberg 1995; Käär et al. 1998). Multiple studies have demonstrated how some men, whether because they are tall (Mueller and Mazur 2001; Nettle 2002; Pawlowski 2000), rich (Borgerhoff Mulder 1988; Pollet and Netting 2007; Weeden et al. 2006), or otherwise viewed as attractive (see review in Gangestad and Simpson 2000), are more successful at accruing mates and producing children than others. Such men can marry multiply, even in a prescriptively monogamous society, through a strategy of divorce and remarriage that excludes less-competitive men from the marriage market (Buckle et al. 1996; Lockard and Adams 1981). Women, in contrast, are generally thought to suffer from divorce, either in terms of time loss (Buckle et al. 1996), stepfather interference with children of a previous mate (Daly and Wilson 1985), or fitness costs for offspring of unstable or broken marriages (Flinn 1988).

In this paper I argue that the currently dominant model of parental investment typically brought to the evolutionary study of human mating systems obscures some unpredicted but perhaps quite general patterning to the reproductive and sexual strategies of women. Preliminary data from a horticultural population in Tanzania practicing serial monogamy show that men and women do not have significantly different variances in reproductive success, and that women rather than men benefit from multiple marriages.

What Shapes Sex Roles? New Insights from Behavioral Ecology

The study of the sexual and reproductive strategies in mammals has been dominated by models predicated on the differential postzygotic investment of males and females. In systems where gestation and lactation fall exclusively to females, where paternity certainty is never assured, and where paternal care is facultative, male fitness is seen as limited by competition over mates, and female fitness by access to resources (Emlen and Oring 1977; Wrangham 1980). Evolutionary anthropologists were quick to see the relevance of these ideas for humans, particularly the notion of a limited (male) and limiting (female) sex. They energetically documented the prevalence of competition among men over women (Betzig 1986; Chagnon 1988; Daly and Wilson 1988; Hawkes 1991; Irons 1979), albeit mediated through variable channels, such as political office, violence, wealth accumulation, and the provision of public goods. Similarly they explored how women (or parents on their behalf) choose and compete for mates (Buss 1989; Dickemann 1979; Gangestad and Simpson 2000), again through a range of mechanisms, including cognitive preferences, dowry payments, and olfactory cues.

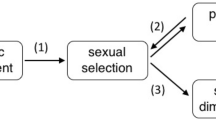

What sparked this explosion of insights on sex differences in mating strategies? While anisogamy lies at the heart of the story (and indeed the evolution of sex itself; Parker et al. 1972), it was Trivers (Trivers 1972; see also Williams 1966) who shifted the focus from gamete to zygote. By linking sex roles to relative post-zygotic investment he prompted the exploration of selective factors beyond those favoring anisogamy. With this simple step he drew attention to a new causal factor, parental investment, arguing that the lesser-investing sex (usually males) will be the more competitive and indiscriminate in its mating behavior while the greater-investing sex (usually females) will be more discriminating in its choice of mating partners. Grafting this logic onto Bateman’s (1948) classic findings regarding sex differences in the fitness benefits of mating with multiple mates, he provided an influential explanation for the distinct sex roles of males and females and their variability across taxa. Specifically his model drew attention to sex differences in the trade-offs between mate number and mate quality.

Over the years, however, there has been a blossoming of theoretical and empirical work in behavioral ecology that explores the influence of factors other than parental investment in shaping sex roles. First, both theoretical and empirical work shows that anisogamy does not always produce classic sex roles (Gowaty 2004; see also Snyder and Gowaty 2007) and also that competition and choice are neither mutually exclusive (Kokko 2006), as has long been recognized empirically in studies of nonhuman primates (Hrdy 1986), nor intrinsically linked to mating systems—for example, an individual can both be choosy in terms of mate choice and mate multiple times. In other words, choosiness is not simply a function of operational sex ratios, with the limiting sex enjoying the luxury of choice. One factor influencing choosiness is variance in mate quality; it is only worth paying the costs of choice if there are substantial gains to be earned from being picky (Johnstone et al. 1996; Owens and Thompson 1994). Another much-overlooked influence on choosiness is sex differences in the costs of reproduction (Kokko and Monaghan 2001; Maness and Anderson 2007); if reproduction is costly, it pays to be more choosy. A third important factor is the extrinsic survival rate (Gowaty and Hubbell 2005; McNamara 1999); for example, female crickets (Gryllus integer) change from choosy to indiscriminate under increasing predation risk (Hedrick and Dill 1993). Indeed, modeling shows that, because of these additional considerations, indiscriminate male and choosy female behaviors can be maladaptive even in systems where females exceed males in offspring care, latency to remating, and where their reproductive rate is lower than that of males (Gowaty and Hubbell 2005). These additional selective considerations can in part be thought of as recognition that males and females are limited by very different factors and therefore face distinct opportunities and constraints on their strategies (Clutton-Brock 2009). Recognition of this generates a much richer set of predictions about how competition and choice can be entailed in the strategy of each sex, and how they may vary over the lifetime and across populations, as recently reviewed by Kokko and Jennions (2008).

Second, it is quite possible that females, despite being the principal caregivers, compete more frequently and more intensively with each other than do males (e.g., Clutton-Brock 2007; Holekamp et al. 1996; Le Bas 2006). In meerkats (Suricata suricatta; Clutton-Brock et al. 2006), and several other cooperatively breeding vertebrates (Hauber and Lacey 2005), females gain greater reproductive benefits from dominance than do males (e.g., Engh et al. 2002) and accordingly are more competitive with one another, demonstrating that sex differences in parental investment are not the only mechanism capable of generating sex differences in reproductive competition (see Clutton-Brock 2009 for a review).

Third, there are two well-documented breeding systems in which females have higher variance in fitness than males—cooperative breeders (both mammalian and avian), where there is a single breeding pair (as mentioned above; Hauber and Lacey 2005), and sex-role-reversed species such as dusky pipefish (Syngnathus floridae; Jones et al. 2000) and wattled jacanas (Jacana jacana; Emlen and Wrege 2004). Indeed, in role-reversed species female fitness increases as a function of the number of reproductive partners (Jones et al. 2000). Hauber and Lacey (2005) use these findings to suggest that both a reversal of parental roles (as in the pipefish) and social suppression (as in some of the cooperative breeders) can be powerful determinants of individual fitness and can modify sex-specific patterns of reproductive variance from the classic pattern described by Bateman. Although the pattern of sexual selection cannot be drawn directly from sex differences in fitness variance (see “Discussion”), these findings do raise questions about some of the basic assumptions we make about the operation of sexual selection in mammals, as reviewed specifically for humans by Brown et al. (2009).

Finally, there is now considerable evidence that females who mate with multiple males are more fertile and show higher offspring survival (as reviewed in Hrdy 2000); in some cases this results from increased paternal provisioning, as in the case of alpine accentors (Prunella collaris; Nakamura 1998) and dunnocks (Prunella modularis; Davies 1992). There is also evidence in the avian literature that females benefit reproductively from divorce more than males do (Dhont 2002).

Here I build on these recent behavioral ecological insights, namely that competition and choice are not the exclusive provenance of males and females, respectively, that females can exceed males in reproductive competition, and that females can have higher variance in reproductive success than males (perhaps through solicitous mate choice), to develop a new suggestion regarding human mating systems: specifically, that women can benefit from multiple pair bonds as much as men (or even more so). The relatively atypical female behavior reviewed above is seen most commonly in sex-role-reversed or cooperatively breeding species (Hauber and Lacey 2005). In humans we might expect the same patterns in societies that would conventionally be characterized as serially monogamous. Other precipitating factors might be populations where males vary significantly in the investments they make in mothers and children, where women can sometimes rely on assistance from their kin, or where women might benefit from the genetic advantages of mating with multiple men. I focus on preliminary data from such a population.

Serial Monogamy

How do these recent developments within the nonhuman literature affect the way we analyze human mating systems? The argument developed here is that we rely too heavily on models based on Bateman’s gradients and parental investment theory (see Brown et al. 2009). To support this argument I will examine serial monogamy. I will derive conventional predictions from parental investment theory regarding expected outcomes associated with serial monogamy and test them with new data from a postreproductive cohort of men and women in a primarily horticultural population in western Tanzania. The analyses are still somewhat rudimentary, since the data are to be supplemented with more nuanced analyses of currently reproducing individuals. Nevertheless the data at hand demonstrate that there are populations where women seem to lead sexual and reproductive lives that are very different from those derived from a Bateman-Trivers model.

Serial monogamy is typically viewed by evolutionary anthropologists as a form of polygyny—in other words, a strategy whereby some men monopolize more than a single female reproductive lifespan through repeated divorce and remarriage (e.g., Starks and Blackie 2000, for contemporary US society). This can be done through various means, such as marrying women younger than themselves, and replacing divorced spouses with women younger than the previous spouse (as shown in Utah; Kunz and Kunz 1994); both of these strategies effectively lengthen the reproductive lifespans of some men relative to those of women. Indications that men show higher variance in reproductive success than women, even in strictly monogamous systems, come from historical studies in Sweden (reviewed in Low 2000), Germany (Voland 1998), and the US (Starks and Blackie 2000), though see Brown and Horta (1988) for a different situation in the Pitcairn Islands. These effects are usually achieved through multiple marriage (Forsberg and Tullberg 1995; Mueller and Mazur 2001) or presumed extramarital reproduction (Hopcroft 2006).

If serial monogamy is a form of polygyny, we predict that men (compared with women) are more likely to have never married (Prediction 1.1) and to have higher variance in reproductive success (1.2). Looking only at ever-married individuals, the prediction is that men have more spouses than women (2.1), and men remarry more rapidly after a divorce or widowing in first marriage than do women (2.2). To gain reproductive years, men marry women younger than themselves (3.1) and marry replacement wives who are younger than their predecessors (3.2). Finally, men are expected to gain more reproductive benefits from multiple marriages than do women (4).

Ethnographic Materials and Demographic Methods

Demographic records come from a single village (Mirumba), representative of a primarily horticultural population in western Tanzania, the Pimbwe, residing in the Rukwa Valley (Mpimbwe Division, Mpanda District). The area is low elevation, characterized by flat and undulating terrain, has sandy soils, and consists largely of a dry deciduous (miombo) woodland and seasonal floodplains, with an annual rainfall of 750 mm/year that falls between November and April. The village lies at the north end of the Rukwa Valley at latitude 7˚05′S, longitude 31˚04′E. Until the mid twentieth century Pimbwe were mixed farmer-foragers, relying heavily on fishing, hunting, honey production, and their small gardens of cassava (Willis 1966).

Impacts from German, Belgian, and British colonial escapades in this central African region were indirect since the region primarily served as a labor reserve (Tambila 1981). More severe were the effects of colonial wildlife policies. First in the 1920s, then in the 1950s, and most recently in 1998 areas protected initially for trophy hunting and more recently for wildlife tourism were established, rendering habitation, fishing, and hunting illegal in much of the Pimbwe traditional lands (Borgerhoff Mulder et al. 2007). In the peak of the socialist era (mid 1970s) Pimbwe families were settled in government villages, but many have now returned to ancestral lands that lie outside wildlife protected areas. Mpanda District is one of the poorest in the country, with between 40% and 50% of households below the basic needs poverty line (United Republic of Tanzania 2005), probably an underestimate for Mpimbwe, which lies far from the District town. Poverty largely results from poor transport and infrastructural development; there are no surfaced roads, and virtually no houses have electricity or running water. Furthermore, economic progress in the whole region is seriously impeded by activities related to witchcraft (Kohnert 1996).

Pimbwe rely on maize as a staple subsistence and cash crop, with additional cash crops (peanuts, sunflower, tobacco) and food crops (beans, sugar cane, banana, tomato, sweet potato, millet, and pumpkin) supplemented by greens collected in the bush; less than 10% of families keep goats, but many attempt poultry keeping. Unlike the Sukuma who have moved into the region, they keep no cattle. There are a number of additional economic activities, such as trading, traditional medicine, hunting, fishing, honey production, and carpentry for men, and beer brewing for women. For several reasons livelihoods are unpredictable. First, the highly seasonal rainfall leads to critical periods of food shortage and labor demand (Hadley et al. 2007; Wandel and Homboe-Ottesen 1992) that create serious stresses for women (Hadley and Patil 2006). Second, the poor infrastructure makes cash cropping risky; sacks of uncollected produce can be observed rotting on roadsides. Third, health services are minimal, making disease a constant threat. Fourth, educational facilities are extremely poor, such that remittances from salaried relatives living in town are negligible.

The traditional marriage pattern, reported as clan controlled, monogamous, exhibiting low divorce rates, and accompanied by bridewealth (Willis 1966), must have been seriously challenged by the high rates of labor outmigration in the colonial period (Tambila 1981). Marriage increasingly became a pattern of cohabitation associated with an optional transfer of bridewealth and a celebration. Polygyny appears never to have been common. Nowadays marriage can be defined as sharing in the production and consumption of food and shelter, with the expectation of exclusive sexual relations. Marriages are very often precipitated by pregnancy, such that number of marriages in this population probably closely approximates the number of individuals with whom a man/woman has regular sexual relations. Divorce has become much more common, perhaps reflecting curtailed male economic roles with the restrictions on hunting (see above) and, like marriage, can be defined by the physical movement of one partner out of the house, requiring no legal or formal procedures. Often divorces occur when one spouse starts an extramarital relationship, with both sexes tending to claim (at least to the anthropologist) responsibility for abandoning the relationship. After the divorce, children under the age of 8 are supposed to go (or stay) with the mother (or the mother’s kin), whereas older children should go (or stay) with their father. In reality the fate of children is quite variable. Sometimes fathers “kidnap” very young children from their mothers, sometimes mothers leave a recently weaned child with a divorced husband. Older children may live with a range of maternal or paternal kin and may desperately try to track down the whereabouts of their biological parents (sometimes calling on the anthropologist’s help).

Given these residence patterns, parental care is highly facultative. Regarding direct care, typically wives take primary responsibility for small children, with assistance from older children and/or other kin, including their own mothers. Regarding indirect care, the bulk of farming is done by husbands and wives, but there is considerable variability within marriages as to how the fruits of joint farm labor are allocated among family subsistence needs, joint family benefits (like health and education), individual cash purchases, or capital for individual economic enterprises (for example, using maize for beer brewing). These allocations prompt frequent spousal arguments; indeed a man or his wife will sometimes place a lock on the family granary to exclude “inappropriate” use by their spouse. Finally, with respect to transmitted resources there are no significant heritable resources in this population; men and women get access to land and houses opportunistically from maternal or paternal relatives who happen to have unused land or living sites available in the village, and otherwise there is very little to inherit in the way of bequests.

Basic demographic data were collected in all Mirumba households in six different study periods between 1995–1996 and 2006. Each round provides a check on previous records in addition to furnishing a longitudinal record of deaths, births, marriages, divorces, and the residential trajectory of individuals between different households. The flexibility of marital and residence patterns made the collection of demographic records over an 11-year period challenging. Fortunately, names are constant, and in almost all cases a child is given the name of the man the mother believes is its father; if a mother wants to conceal (or does not know) the father of her child, she gives her child her father’s name. Every household in the village was censused each demographic round to avoid missing unstable households or children who might be overlooked in a sampling scheme based on a random selection of households identified by village leaders or easily identifiable distinct structures. The sex ratio of the whole village in 2006 is slightly female-biased: 96:100, or 97:100 if restricted to individuals over 15 years of age. Only the reproductive/marital records of individuals recorded in the village on one or more occasion are included in the sample—in other words, not reports on previous spouses in other villages, even if complete. On three occasions (1998, 2002, 2004) the majority of household heads (male and female of all ages) were classified by a group of 3–5 village women living in different parts of the village to determine work ethic (works hard/works/lazy) and drinking habits (drinks heavily/drinks/light drinker or does not drink; a great deal of locally brewed maize beer and spirits are available in the village almost on a daily basis). Data were available for 252 (86%) of the 292 men and women in the reproductive sample (below). When more than one ranking was available, rankings were consistent for 85% of the sample; discrepancies were solved using the modal ranking, or in the absence of a mode, the most favorable (most hardworking, least drinking) value.

Analyses presented here include only individuals who are assumed to have completed their reproduction (>45 years of age). The sample consists of 138 men with a mean age of 60.3 years (range 45.3–92.7) and 154 women with a mean age of 59.2 years (range 45.0–86.8). Although men can and do reproduce beyond this age, this same cutoff was used to make the samples comparable, and age was controlled in all analyses. To ensure results were not an artifact of curtailing men’s later potential reproductive lifespan, all tests were rerun, dropping men who had not yet reached their fifty-fifth birthday (see caption to Fig. 1).

Variance in (a) fertility and (b) reproductive success for men and women who have reached their forty-fifth birthday. The sex difference in variance in fertility is significant, but not the sex difference in reproductive success (see text). Comparing women with men who have reached their fifty-fifth birthday (n = 87) shows no significant differences in variances for fertility or reproductive success (see text)

The majority of the sample are ethnic Pimbwe, but a small percentage (15%) are Fipa, Rungwe, Konongo, or other related ethnicities represented in the Rukwa Valley; the few Sukuma families with houses in the village were dropped because of their very different (polygynous) family system (Paciotti et al. 2005).

Variables used in the analysis were sex, number of spouses over the lifetime, age (based on self reports, birth cards, or estimates of kin), number of live births, and (as a measure of reproductive success) the number of offspring surviving to five years of age, beyond which mortality is low. Speed of remarriage was estimated in two ways: (a) the mean interval between marriages (closed intervals only, n = 91 owing to missing marriage years) and (b) the interval of time since last divorce or widowing to the latest census or death (latest intermarriage interval), coded according to whether or not a remarriage had occurred (n = 138). To examine spousal age differences the dataset was restructured as independent marriages (n = 156 with known spousal ages); a much smaller sample of these marriages (n = 21) also had data on the age of the replaced spouse at death or divorce. The statistical tests used are noted in the results.

Results

If serial monogamy is a form of polygyny, men should be more likely than women to have never married (prediction 1.1). Among men and women who had completed their reproductive careers only 3 (2.2%) men and 2 (1.3%) women had never married, indicating that marriage is virtually universal (Table 1).

Prediction 1.2, that men have higher reproductive variance than women, is supported for fertility but not for reproductive success (children surviving to five years). The variances in reproductive performance for both sexes are shown in Fig. 1.Footnote 1 Although men show greater fertility variance (16.16) than women (11.34; Levene’s test for equality of variances F = 5.87, p = 0.016), for completed reproductive success there is no difference in the variance (men = 9.00; women = 7.27, Levene’s test F = 2.15, p = 0.15). Furthermore, restricting the analysis to compare women past their forty-fifth birthday with men past their fifty-fifth birthday (n = 87), to allow for the fact that men can reproduce at older ages and may be gaining greater fitness in later years, revealed no significant differences in variance, neither in fertility (men’s variance = 13.97, Levene’s test F = 1.007, p = 0.317) nor in reproductive success (men’s variance = 7.87, Levene’s test, F = 0.317, p = 0.574).

When only ever-married individuals were considered, the expectation was that men marry multiply more than do women (2.1), and remarry more rapidly after divorce or widowing (2.2). Regarding the first prediction men do indeed exceed women in their multiple marriages (Table 1). The probability of marrying more than one spouse (i.e., 1 vs. >1 spouse) varies as a function of sex (logistic regression: Wald 5.79, p = 0.016), age (5.09, p = 0.024), and their interaction (6.79, p = 0.009), with women being less likely to marry more than one spouse than men, and to do so less as they age. In terms of the speed of remarriage, the data are somewhat contradictory. The mean interval between divorce or widowing and remarriage, as averaged over the lifespan, is shorter for men (3.42 years, SE = 0.62) than for women (4.56 years, SE = 0.88), but the difference is not statistically significant (t = 1.091, df = 89, p = 0.278). However, a survival analysis (using Cox’s regression) of the latest intermarriage interval for Pimbwe men and women shows significant effects of sex, age, and their interaction (Fig. 2). In effect, as they age men marry more quickly than women after a divorce or widowing.

To gain reproductive years men are predicted (3.1) to marry younger women, and they do (matched-pair t-test = 13.18, df = 155, p < 0.001). However, the more crucial prediction for serial monogamy being a strategy whereby men gain reproductive years is that they replace their deceased or divorced wives with a younger woman (3.2). For the 21 marriages in which the age of the original and replacement wives are known, there is no evidence that men replace divorcees/widows with younger women (matched-pair t-test = 1.331, df = 20, p = 0.198), although the test has little power because of the small sample.

Finally, men are expected to gain more reproductive benefits from multiple marriages than do women (prediction 4). Fertility (Fig. 3a) and numbers of offspring reaching 5 years of age (Fig. 3b) are shown in relation to number of spouses (1, 2, and 3 or more) and an unexpected pattern emerges. Whereas men fail to benefit in terms of fitness from multiple marriages, women (at least those who marry three or more times) are favored in terms of production of surviving children. Fertility (Table 2a) and completed reproductive success (Table 2b) were regressed on age, sex, and number of spouses in a number of different models. Generally, across models, number of spouses is negatively associated with fertility and number of surviving offspring, and interaction effects between spouse number and sex reflect the pattern shown in Fig. 3, namely that men suffer reproductively from multiple marriages in a way that women do not. The models also show that age is positively associated with fertility, and less pronouncedly with reproductive success, suggesting (in this postreproductive sample) that levels of fertility were higher in cohorts that finished reproduction in the 1970s than in the 1990s, which is to be expected in a community in the early stages of demographic transition.

The associations between number of spouses and (a) fertility and (b) reproductive success for men and women. The mean is shown with a circle, and the standard error (*2) with a bar. For statistics see Table 2

The particularly high fitness of women and low fitness of men in high-order marriages prompted a cross-tabulation of number of spouses with results from a participatory research methodology designed to categorize men and women according to various characteristics. Although classifications of work and drinking habits were not available for the full sample, a chi-square test for linear association showed that men with single marriages were more likely to be “hardworking” (and less likely to be “lazy”) than men with two, and particularly three, marriages. The opposite pattern was found for women—namely, a higher proportion of women in third marriages were “hardworking” than those with only one or two marriages (Fig. 4). The results for alcohol consumption showed a weaker pattern, and only for men. Among men with three or more spouses, “heavy” drinkers predominate, although this is only marginally significant; there is no pattern to the drinking habits of women (Fig. 5).

Discussion

The predictions generated by the view of serial monogamy as polygyny found little consistent support in this study (Table 3). First, there is no evidence that men are less likely to have ever married than women. Second, variance in reproductive success is not statistically significantly higher for men than women. Looking only at married individuals, men do indeed marry more spouses over their lifetimes than do women. Results for the speed of remarriage after a widowing or divorce are inconsistent; the average waiting period between a divorce (or widowing) is no shorter for men than women, but in the most recent intermarriage interval men replace their spouses more rapidly than do women, with women delaying longer as they age. Furthermore, while men marry wives who are younger than themselves (an almost universal finding), the more precise prediction that they replace those wives with relatively younger women is not supported (although the power of this test is weak). Since the sex ratio is very close to unity, these results suggest more than simple demographic constraint. Finally, there is no evidence that men benefit from multiple marriages more than do women; in fact, the beneficiaries of third and higher-order marriages are women.

Severe limitations to the current analyses must be acknowledged. It would be analytically much cleaner to look at the probability of bearing a child, or the probability of raising a child to age five, as a function of the marital status of the parents. Currently, overall reproductive performance is analyzed simply in relation to the number of spouses married over the lifetime. Furthermore, the findings do not take into account the marital status of the spouse. It is tempting to think that women who have married many husbands are married to men who have had many wives, but this is not necessarily the case given the structure of the sample. Finally empirical analyses of economic performance (in progress) will be far preferable to reported work ethic, although for the families I know well these rankings were very accurate. The findings, while illuminating, are therefore not conclusive. New work with a larger dataset that includes currently reproductive women and analyzes production of children per year suggests a similar pattern (Borgerhoff Mulder 2009).

Regarding fitness variances, it is clear that sex differences are not pronounced. Men show greater variance in fertility than women, at least in the sample of individuals who had reached their forty-fifth birthday. After excluding men who had not yet passed their fifty-fifth birthday the statistical significance disappears, suggesting a cohort effect, namely that it is younger men who are showing higher sex-specific variance in fertility. Furthermore in both samples the number of children surviving to age five is not significantly different between the two sexes, suggesting that men with very high fertility successfully raise few of these “extra” children. Recent theoretical work demonstrates that secure conclusions about the operation of sexual selection cannot be drawn from observations about sex differences in variance. This is because variation can arise from random, non-heritable factors (Hubbell and Johnson 1987; Sutherland 1985). Much more important for our understanding of reproductive strategy is the relationship between breeding success and physiological or behavioral phenotypes (Clutton-Brock 1988), and therefore we turn to partner number.

A key finding here is that while men do not benefit from multiple marriages, women do (at least in higher-order marriages). Although the data are very variable (large standard errors), women appear to gain more from multiple mating than do men. Furthermore, results from the ranking exercise indicate that the men who engage in many marriages tend to be “lazy” workers and “heavy” drinkers, whereas the women who marry multiple times tend to be “hard” workers.

These findings raise two questions. First, what parallel evidence do we have for other populations, human or nonhuman, and second, what are the possible explanations? Regarding parallel evidence, I know of no cases in which males (nonhuman or human) fail to benefit from multiple serial mates; the Pimbwe case is therefore unique (as discussed below). For females the number of reproductive partners is associated with fitness in sex-role-reversed and other species, as discussed in the section on behavioral ecology above, reflecting either direct contributions to the protection and nutrition of offspring or possibly indirect benefits arising from female choice for high-quality males. In humans there are indications from South American “partible paternity” cultures (where women have sexual relations with more than one man) that children born with “secondary” fathers have higher survival rates than children born without “secondary” fathers—for example, among the Bari (Beckerman et al. 1998, where one but not two secondary fathers is beneficial) and the Ache (Hill and Hurtado 1996), an effect attributed to the gifts and protection the co-fathers provide. Overall effects of multiple paternity on a woman’s fitness are not known, although modeling suggests such systems might thrive at in populations with female-biased sex ratios (Mesoudi and Laland 2007), not apparently characteristic of the Pimbwe population. In terms of more typical marriage systems, women’s second marriages are much less productive than their first marriages (e.g., Käär et al. 1998, for the preindustrial Sami in Finland), such that there is no net benefit of multiple marriages to women. Forsberg and Tullberg’s (1995) study of modern Sweden shows a fitness benefit to men of serial marriages but also concludes that there are no reproductive benefits of remarriage to women. Rather amazingly, I could find no evidence in the demographic, sociological, or economic literature on how divorce affects women’s overall fitness in other Western populations; it is simply assumed that the reduced period at risk dominates any selection effects such as non-marital fertility (pregnancy prompting a new marriage). Recent data from the Indian Khasi (Leonetti et al. 2007) suggest that women in second marriages have shorter interbirth intervals than women in first marriages, although it is unclear how much of this effect is attributable to the fact that most women in second marriages are not living with their mothers (who appear to be protective against high fertility); furthermore, the implications for the overall fitness of women in multiple versus single marriages are not examined. In short, the reproductive benefit of multiple marriages to women requires much further empirical scrutiny.

The remaining question then is why do Pimbwe men and women mate multiply? One possibility is that multiple marriages result from male coercion (Smuts 1992). Marriages and divorces are often precipitated by pregnancies. Insofar as high-order marriages are common among the heavy drinking and slack working men in Mpimbwe, these men’s multiple marriages might reflect an associated lax sociosexual lifestyle. Nevertheless, men in multiple marriages do not father more children, so unless all such pregnancies end up in miscarriage, this is unlikely to be the sole route to multiple marriage. Ethnographic observations drawn from household surveys suggest that lazy and heavy-drinking men are often divorced and end up marrying postreproductive women, often for economic support in raising their dependent children. Their multiple marriages may therefore, rather counter-intuitively, reflect a parental rather than a mating strategy, although who exactly marries these men remains a puzzle.

Why might women marry multiply in Mpimbwe? The host of hypotheses in the literature (e.g., Jennions and Petrie 2000) can be separated into direct and indirect benefits. With respect to direct benefits, women may mate with and marry multiple men to obtain the resources needed to support reproduction. This explanation seems quite plausible in that women can benefit from the farming activities of men, as well as from the products of their hunting, fishing, honey production, and other enterprises. Men’s provisioning activities are highly unpredictable, in part because of poor farming conditions and in part because of the current illegality of utilizing many natural resources (Borgerhoff Mulder et al. 2007). Given the potentially high inter- and intra-individual variability in men’s provisioning abilities (see ethnography, above) it is quite possible that women switch mates to maximize economic income, the “musical chairs” hypothesis reviewed by Choudhury (1995; see also Maness and Anderson 2007). These findings for the Pimbwe suggest parallels with Schuster’s (1979) “new women of Lusaka,” who marry and remarry in search of supportive husbands, as well as Malawian women who use sexual relations to negotiate dependencies somewhat akin to patron-client relationships (Swidler and Cott Watkins 2007). Similar arguments have been made for the instability of marriages among the poor in the contemporary USA (Kaplan and Lancaster 2003). There are also some similarities with baboons, among which serial if nonexclusive pair bonds produce temporary male protectors for mothers (whose reproductive success is heavily influenced by social networks and matrilineally inherited resource access, as reviewed in Silk 2007). The idea here then is that hardworking women have higher mate-choice standards and do not put up with lower-quality mates. However, without further analysis of the economic data, and of the initiation of divorce, it is not yet possible to determine the validity of this explanation. Furthermore, it is somewhat odd that the women who marry more than two times are for the most part very hardworking and presumably relatively economically independent; for them the marginal benefits of men’s contributions would be lowest, suggesting the need to consider indirect benefits.

As regards indirect (or genetic) benefits, numerous mechanisms have been proposed (including the maximization of male genetic potential, bet hedging, prevention of inbreeding, and confusion of paternity certainty to avoid infanticide). The most plausible in this context is the idea that a woman can afford to forgo the benefits of paternal care (and to risk the dangers of a stepfather in the house) for mates with high genetic potential. This argument has been made most forcefully for humans by Gangestad and Simpson (2000), and it is particularly plausible in environments with high disease loads where demonstration of heritable fitness is so important (Hamilton and Zuk 1982). In support of this explanation is the fact that the division of Mpimbwe is beset by all of the health problems typical of rural tropical Africa (Hadley 2005; Hadley and Patil 2006; Hadley et al. 2007) and minimal health care infrastructure. In addition, it is the economically autonomous women who appear to be most concerned with potential genetic quality. On the other hand, female choice for indirect benefits is usually associated with polygyny (Hamilton 1982; Low 1990) insofar as males with heritable resistance to disease are differentially attractive to females. If choice for good genes were the explanation in this population we would expect a correlation between a man’s number of partners and fitness, which we do not find. Indeed, indirect benefits could only be driving polyandry if pathogen evolution is rapid, such that there is no single “best” male, or if mate choice is self-referential, such that there are many “best” males (Roth et al. 2006).

Conclusion

The Pimbwe results suggest that we should think about serial monogamy as a form not just of polygyny but also of polyandry. This finding will not surprise authors such as Sarah Hrdy, Barbara Smuts, and Patty Gowaty, who have been encouraging human behavioral ecologists to focus more on the strategies of women. However, this plea is usually interpreted as a call to pay more attention to the female side of the conventional model—male competition and female choice. The argument here is that we need to revise the simple Triversian assumptions, and more specifically that the source of our limited understanding of women’s strategies lies in an overemphasis on the parental investment model. Pimbwe women, despite being the principal investors, mate multiply, and may be doing so because of being so choosy, although this appears not to be a strategy open to all women. Mate number and mate quality are not necessarily traded off against each other.

This paper also offers albeit very preliminary empirical evidence depicting the nature of women’s strategies in serial monogamy (though further analysis is still required). Sarah Hrdy (2000:82) was on the right track when she appended to her question “Why is polyandry so rare in humans?” another question: “Or is it?” Hrdy drew the distinction between the extremely rare cases of “formal polyandry,” in which women marry groups of men simultaneously, and the possibly much more common “informal polyandry,” both of which result from a constellation of factors, including a shortage of women (Peters and Hunt 1975), the difficulty for a single man to make adequate provisions for a family (Haddix 2001), and the custom of men sharing their wife or wives with potential allies (see discussion in Hrdy 2000). This informal polyandry Guyer (1994) labeled as “polyandrous motherhood,” depicting the reproductive careers of women who raise the children of different men (e.g., Schuster 1979). Although the term has not caught on, the idea has—for example, in recent work on how African women’s relationships with multiple men are not prostitution but long-term transactional strategies for making good in life (Swidler and Cott Watkins 2007). My point then is that polyandry is everywhere, but by labeling it as serial monogamy we tend to think of it as polygyny!

As Linda Mealey (2000) so perspicaciously noted, those rare, exotic polyandrous cases in which women marry groups of men, often brothers, have garnered a lot of interest. However, the much more common pattern of women mating with multiple men over their lifetime is simply referred to as serial monogamy, and has conventionally been seen as a male strategy. I have argued here that this is because conventional parental investment theory has led us to believe that serial monogamy is simply another form of polygyny, and I have presented data to suggest that we may learn more about human nature by studying serial monogamy with a more open mind, and maybe even giving it its real name—polyandry.

Notes

-

The mean values of fertility (men = 8.41; women = 8.17) and number of surviving offspring (men = 5.99; women = 6.14) are not statistically different from each other, which suggests that there is no distortional sex bias to the sample.

References

Bateman, A. J. (1948). Intrasexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity, 2, 349–368.

Beckerman, S., Lizarralde, R., Ballew, C., Schroeder, S., Fingelton, C., Garrison, A., et al. (1998). The Bari partible paternity project: Preliminary results. Current Anthropology, 39, 164–167.

Betzig, L. L. (1986). Despotism and differential reproduction: A Darwinian view of history. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (1988). Reproductive success in three Kipsigis cohorts. In T. H. Clutton-Brock (Ed.), Reproductive success, pp. 419–435. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2009). Tradeoffs and sexual conflict over women’s fertility preferences in Mpimbwe. American Journal of Human Biology. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20885.

Borgerhoff Mulder, M., Caro, T. M., & Msago, A. O. (2007). The role of research in evaluating conservation strategies in Tanzania: The case of the Katavi-Rukwa ecosystem. Conservation Biology, 21, 647–658.

Brown, D. E., & Horta, D. (1988). Are prescriptively monogamous societies effectively monogamous? In L. Betzig, M. Borgerhoff Mulder & P. W. Turke (Eds.), Human reproductive behaviour: A Darwinian perspective, pp. 153–159. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, G. R., Laland, K. N., & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2009). Bateman’s principles and the evolution of human sex roles. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, (in press).

Buckle, L., Gallup, G. G., & Rodd, Z. A. (1996). Marriage as a reproductive contract: Patterns of marriage, divorce, and remarriage. Ethology and Sociobiology, 17, 363–377.

Buss, D. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences. Brain and Behavioral Sciences, 12, 1–49.

Chagnon, N. (1988). Life histories, blood revenge, and warfare in a tribal population. Science, 239, 985–939.

Choudhury, S. (1995). Divorce in birds: A review of the hypotheses. Animal Behavior, 50, 413–429.

Clutton-Brock, T. (ed). (1988). Reproductive success: Studies of individual variation in contrasting breeding systems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clutton-Brock, T. (2007). Sexual selection in males and females. Science, 318, 1882–1885.

Clutton-Brock, T. (2009). Sexual selection in females. Animal Behaviour, 77, 3–11.

Clutton-Brock, T. H., Hodge, S. J., Spong, G., Russell, A. F., Jordan, N. R., Bennett, N. C., et al. (2006). Intrasexual competition and sexual selection in cooperative mammals. Nature (London), 444, 1065–1068.

Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1985). Child abuse and other risks of not living with both parents. Ethology and Sociobiology, 6, 197–210.

Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Evolutionary social psychology and family homicide. Science, 242(4878), 519–524.

Davies, N. B. (1992). Dunnock behaviour and social evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dhont, A. A. (2002). Changing mates. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 17, 55–56.

Dickemann, M. (1979). The ecology of mating systems in hypergynous dowry systems. Social Science Information, 18, 163–195.

Emlen, S. T., & Oring, L. W. (1977). Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science, 197, 215–223.

Emlen, S. T., & Wrege, P. H. (2004). Size dimorphism, intrasexual competition, and sexual selection in wattled jacana (Jacana jacana), a sex-role-reversed shorebird in Panama. Auk, 121, 391–403.

Engh, A. L., Funk, S. M., Van Horn, R. C., Scribner, K. T., Bruford, M. W., Libants, S., et al. (2002). Reproductive skew among males in a female-dominated mammalian society. Behavioral Ecology, 13, 193–200.

Flinn, M. V. (1988). Mate guarding in a Caribbean village. Ethology and Sociobiology, 9, 1–28.

Forsberg, A. J. L., & Tullberg, B. S. (1995). The relationship between cumulative number of cohabiting partners and number of children from men and women in modern Sweden. Ethology and Sociobiology, 16, 221–232.

Gangestad, S. W., & Simpson, J. A. (2000). The evolution of human mating: Trade-offs and strategic pluralism. Behavior and Brain Sciences, 23, 573–644.

Gowaty, P. A. (2004). Sex roles, contests for the control of reproduction, and sexual selection. In P. M. Kappeler & C. P. van Schaik (Eds.), Sexual selection in primates: New and comparative perspectives, pp. 37–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gowaty, P. A., & Hubbell, S. P. (2005). Chance, time allocation, and the evolution of adaptively flexible sex role behavior. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 45, 931–944.

Guyer, J. (1994). Lineal identities and lateral networks: The logic of polyandrous motherhood. In C. Bledsoe & G. Pison (Eds.), Nuptiality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Contemporary anthropological and demographic perspectives, pp. 231–252. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Haddix, K. (2001). When polyandry falls apart: Leaving your wife and your brothers. Evolution and Human Behavior, 22, 47–60.

Hadley, C. A. (2005). Ethnic expansions and between-group differences in children’s health: A case study from the Rukwa Valley, Tanzania. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 128, 682–692.

Hadley, C., & Patil, C. L. (2006). Food insecurity in rural Tanzania is associated with maternal anxiety and depression. American Journal of Human Biology, 18, 359–368.

Hadley, C., Borgerhoff Mulder, M., & Fitzherbert, E. (2007). Seasonal food insecurity and perceived social support in rural Tanzania. Public Health Nutrition, 10, 544–551.

Hamilton, W. D. (1982). Pathogens as causes of genetic diversity in their host populaton. In R. M. Anderson & R. M. May (Eds.), Population biology of infectious diseases, pp. 269–296. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hamilton, W. D., & Zuk, M. (1982). Heritable true fitness and bright birds: A role for parasites? Science, 218, 384–387.

Hauber, M. E., & Lacey, E. A. (2005). Bateman’s principle in cooperatively breeding vertebrates: The effects of non-breeding alloparents on variability in female and male reproductive success. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 49, 903–914.

Hawkes, K. (1991). Showing off: Tests of an hypothesis about men’s foraging goals. Ethology and Sociobiology, 12, 29–54.

Hedrick, A. V., & Dill, L. M. (1993). Mate choice by female crickets is influenced by predation risk. Animal Behavior, 46, 193–196.

Hill, K., & Hurtado, A. M. (1996). Aché life history: The ecology and demography of a foraging people. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Holekamp, K. E., Smale, L., & Szykman, M. (1996). Rank and reproduction in the female spotted hyena. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility, 108, 229–237.

Hopcroft, R. L. (2006). Sex, status and reproductive success in the contemporary US. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 104–120.

Hrdy, S. B. (1986). Empathy, polyandry, and the myth of the coy female. In R. Bleier (Ed.), Feminist approaches to science, pp. 119–146. New York: Pergamon Press.

Hrdy, S. B. (2000). The optimal number of fathers: Evolution, demography, and history in the shaping of female mate preferences. In D. LeCroy and Peter Moller (Eds.), Evolutionary perspectives on human reproductive behavior (pp. 75–96). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 907.

Hubbell, S. P., & Johnson, L. K. (1987). Environmental variance in lifetime mating success, mate choice, and sexual selection. American Naturalist, 130, 91–112.

Irons, W. (1979). Cultural and biological success. In N. A. Chagnon & W. Irons (Eds.), Evolutionary biology and human social behavior, pp. 252–272. North Scituate: Duxbury Press.

Jennions, M. D., & Petrie, M. (2000). Why do females mate multiply? Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 72, 21–64.

Johnstone, R. A., Reynolds, J. D., & Deutsch, J. C. (1996). Mutual mate choice and sex differences in choosiness. Evolution, 50, 1382–1391.

Jones, A. G., Rosenqvist, G., Berglund, A., Arnold, S. J., & Avise, J. C. (2000). The Bateman gradient and the cause of sexual selection in a sex-role-reversed pipefish. Proceedings of the Royal Society (London), B: Biological Sciences, 267, 677–680.

Käär, P., Jokela, J., Merilä, J., Helle, T., & Kojola, I. (1998). Sexual conflict and remarriage in preindustrial human populations: Causes and fitness consequences. Evolution and Human Behavior, 19, 139–151.

Kaplan, H. S., & Lancaster, J. B. (2003). An evolutionary and ecological analysis of human fertility, mating patterns, and parental investment. In K. W. Wachter & R. A. Bulatao (Eds.), Offspring: Human fertility behavior in biodemographic perspective, pp. 170–223. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Kohnert, D. (1996). Magic and witchcraft: Implications for democratization and poverty-alleviating aid in Africa. World Development, 24, 1347–1355.

Kokko, H., & Monaghan, P. (2001). Predicting the direction of sexual selection. Ecology Letters, 4, 159–165.

Kokko, H., & Jennions, M.D. (2008). Parental investment, sexual selection and sex ratios. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21, 919–948.

Kokko, H., Jennions, M. D., & Brooks, R. (2006). Unifying and testing models of sexual selection. Annual Reviews of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, 37, 43–66.

Kunz, J., & Kunz, P. R. (1994). Social setting and remarriage: Age of husband and wife. Psychological Reports, 75, 719–722.

Le Bas, N. R. (2006). Female finery is not for males. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 21, 170–173.

Leonetti, D. L., Nath, D. C., & Hemam, N. S. (2007). In-law conflict: Women’s reproductive lives and the roles of their mothers and husbands among the matrilineal Khasi. Current Anthropology, 48, 861–890.

Lockard, J. S., & Adams, R. M. (1981). Human serial polygyny: Demographic, reproductive, marital, and divorce data. Ethology and Sociobiology, 2, 177–186.

Low, B. S. (1990). Marriage systems and pathogen stress in human societies. American Zoologist, 30, 325–339.

Low, B. S. (2000). Why sex matters. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Maness, T. J., & Anderson, D. J. (2007). Serial monogamy and sex ratio bias in Nazca boobies. Proceedings of the Royal Society (London), B: Biological Sciences, 274, 2047–2054.

McNamara, J. M., Forslund, P., & Lang, A. (1999). An ESS model for divorce strategies in birds. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (London), B: Biological Sciences, 354, 223–236.

Mealey, L. R. (2000). Sex differences: Developmental and evolutionary strategies. San Diego: Academic Press.

Mesoudi, A., & Laland, K. N. (2007). Culturally transmitted paternity beliefs and the evolution of human mating behaviour. Proceedings of Royal Society (London) B: Biological Sciences 274, 1273–1278.

Mueller, U., & Mazur, A. (2001). Evidence of unconstrained directional selection for male tallness. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology, 50, 302–311.

Nakamura, M. (1998). Multiple mating and cooperative breeding in polygynandrous alpine accentors, I: Competition among females. Animal Behaviour, 55, 259–275.

Nettle, D. (2002). Height and reproductive success in a cohort of British men. Human Nature, 13, 473–491.

Owens, I. P. F., & Thompson, D. B. A. (1994). Sex differences, sex ratios and sex roles. Proceedings of the Royal Society (London), B: Biological Sciences, 258, 93–99.

Paciotti, B., Hadley, C., Holmes, C., & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2005). Grass-roots justice in Tanzania. American Scientist, 93, 58–64.

Parker, G. A., Smith, V. G. F., & Baker, R. R. (1972). The origin and evolution of gamete dimorphism and the male-female phenomenon. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 36, 181–198.

Pawlowski, B., Dunbar, R. I. M., & Lipowicz, A. (2000). Evolutionary fitness: tall men have more reproductive success. Nature, 403, 156.

Peters, J. F., & Hunt, C. L. (1975). Polyandry among the Yanomama Shirishana. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 6, 197–207.

Pollet, T. V., & Netting, D. (2007). Driving a hard bargain: Sex ratio and male marriage success in a historical US population. Biology Letters, 4, 31–33.

Roth, E. A., Ngugi, E., & Fujita, M. (2006). Self-deception does not explain high-rsk sexual behavior in the face of HIV/AIDS. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 53–62.

Schuster, I. M. G. (1979). New women of Lusaka. Palo Alto: Mayfield.

Silk, J. B. (2007). The adaptive value of sociality in mammalian groups. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (London), B: Biological Sciences, 362, 539–559.

Smuts, B. (1992). Male aggression against women. Human Nature, 3, 1–44.

Snyder, B. F., & Gowaty, P. A. (2007). A reappraisal of Bateman’s classic study of intrasexual selection. Evolution, 61, 2457–2468.

Starks, P. T., & Blackie, C. A. (2000). The relationship between serial monogamy and rape in the United States (1960–1995). Proceedings of the Royal Society (London), B: Biological Sciences, 267, 1259–1263.

Sutherland, W. J. (1985). Chance can produce a sex difference in variance in mating success and account for Bateman’s data. Animal Behavior, 33, 1349–1352.

Swidler, A., & Cott Watkins, S. (2007). Ties of dependence: AIDS and transactional sex in rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning, 38, 147–162.

Tambila, A. (1981). A history of Rukwa region (Tanzania) ca 1870–1940: Aspects of economic and social change from precolonial to colonial times. Hamburg.

Trivers, R. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual selection and the descent of man 1871–1971, pp. 139–179. New York: Aldine.

United Republic of Tanzania. (2005). Tanzania poverty and human development report. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota.

Voland, E. (1998). Evolutionary ecology of human reproduction. Annual Reviews of Anthropology, 27, 347–374.

Wandel, M., & Homboe-Ottesen, G. (1992). Food availability and nutrition in a seasonal perspective: A study from the Rukwa region in Tanzania. Human Ecology, 20, 89–107.

Weeden, J., Abrams, M. J., Green, M. C., & Sabini, J. (2006). Do high-status people really have fewer children? Education, income, and fertility in the contemporary U.S. Human Nature, 17, 377–392.

Williams, G. C. (1966). Adaptation and natural selection. Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press.

Willis, R. G. (1966). The Fipa and related peoples of south-west Tanzania and north-east Zambia. London: International African Institute.

Wrangham, R. W. (1980). An ecological model of female-bonded primate groups. Behaviour, 75, 262–300.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the L.S.B. Leakey Foundation and UC Davis for funding, to the Commission for Science and Technology (Dar es Salaam) for permissions, Marietta Kimisha and Jenita Ponsiano for special assistance in data collection, Sarah Hrdy for helpful comments on the manuscript, Shelly Lundberg for suggestions regarding the literature in demography, and four referees for useful suggestions.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Borgerhoff Mulder, M. Serial Monogamy as Polygyny or Polyandry?. Hum Nat 20, 130–150 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9060-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9060-x