-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Frank Costigliola, After Roosevelt's Death: Dangerous Emotions, Divisive Discourses, and the Abandoned Alliance, Diplomatic History, Volume 34, Issue 1, January 2010, Pages 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7709.2009.00830.x

Close - Share Icon Share

Thanks to the fierce winter of 1944–45 in Moscow, historians have a written account revealing how dangerous emotions and divisive discourses developed among U.S. and British officials. Spaso House, the huge, drafty American embassy building, was tough to heat. In December 1944, a kerosene stove was rigged up in the top floor room of Robert Meiklejohn, Ambassador W. Averell Harriman's secretary. Meiklejohn jotted in his detailed diary, “My room is very comfortable now,” and it has become “the usual gathering place in the evening.”1 Evenings the ambassador, his daughter Kathleen, the Pentagon's liaison to the Red Army General John R. Deane, embassy officials including George F. Kennan, British Ambassador Archibald Clark Kerr, Kennan's friend Frank K. Roberts, and liberated American prisoners of war clustered around the stove to review the day, gossip, and grumble. The Soviets dished out lots to grumble about. An embassy official “was going nuts here,” Meiklejohn recorded, “as not a few people appear to do when they stay too long.”2 Many diplomats and journalists were frustrated with their personal lives. They suffered anger, sadness, and even depression from being deprived of “normal” contact with Soviet citizens. The moods and cultural assumptions of these diplomats and journalists shaped how they interpreted Soviet policy and intentions. Their recommendations would have enormous influence once President Franklin D. Roosevelt left the scene.

The breakdown of the Grand Alliance and the formation of the Cold War in 1945–46 were not inevitable. Contingent factors of personality and attitude disrupted Big Three diplomacy following the death of Roosevelt and the defeat of Churchill. Neither the leaders who succeeded these giants, nor the “Soviet experts” who asserted a more decisive role than they had hitherto been allowed to play, shared Roosevelt's or even Churchill's commitment to Big Three accord. Josef Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov had little respect for Harry Truman and disliked Ernest Bevin. In the pivotal weeks after Roosevelt died, Harriman and Deane helped change how U.S. policy and opinion makers talked and thought about the Soviet Union.3 The attitudes and rhetoric of Harriman and Deane helped create a discourse of distrust and disgust. The Soviets were increasingly depicted not as valued allies, but rather as potential enemies, nonhumans, barbarians, and irredeemably evil.

In terms of methodology, this article aims to shrink the exaggerated divide between those historians who focus more on state power and those historians who focus more on discourses and texts. I use here a discursive analysis of conversations around that stove and in Washington and San Francisco to help explain a pivotal event, the shift in U.S. policy and attitudes toward the Soviet Union immediately following FDR's death.

In March 1945, Richard Rossbach, an ex-POW well connected to the New York elite, told those gathered around the stove about his experiences after liberation by the Red Army. Commenting that he “had a much better time with the Germans than with our allies,” he described the Red Army as operating under “primitive and chaotic conditions. … Their men live like animals, forage off the countryside for their food … and fight in a semi-drunken state maintained by a generous ration of vodka.” Soviet officers robbed Americans of their watches at gun point. Living conditions in the Red Army were so stark that many ex-POWs sought out local Poles, who “always welcomed and cared for our men as best they could.”4 The cultural and incipiently political lines of division already seemed obvious: affinities between Americans and Poles and even Germans, in contrast to enmity between Americans and Soviets. “Primitive,”“chaotic,” and animal-like men, who stole for sustenance and robbed allies, appeared not as postwar partners, but as a horde to be contained or fought. Kremlin bosses whose “generous ration of vodka” fueled soldiers' “semi-drunken state” seemed themselves bereft of judgment and a sense of limits. Americans and British reacted with understandable disgust as they saw Soviet soldiers raping, looting, and defecating without restraint. Rossbach and others reported that “rapes are constantly occurring.” Common were “cases of thirty or forty Soviet soldiers raping one woman and then killing her.”5 Searing stories habituated embassy officials to referring to the Soviets as “animal-like people” even when talking about such mundane matters as overcrowded trains.6

The Kremlin's policy of isolating foreigners embittered many of the people who shaped how the Soviets were seen in the outside world. The Russian friends, lovers, and wives of foreigners were subject to arrest, torture, and exile to Siberia. These harsh rules were enforced unevenly, raising both temptation and anxiety. The secret police tended to ease up when relations with the Allies improved and to crack down when they soured.7 Foreigners could feel played like a yo-yo. Meiklejohn commented that “when Stalin is mad at you everybody from the doorman to the bus conductor is mad at you.”8 Soviet citizens sought contact out of curiosity, love, friendship, desire for stockings, or eagerness to talk English. Some started out as informants or began informing once threatened. Sometimes officially conflicting loyalties did not conflict. Llewellyn “Tommy” Thompson, who decades later would become John F. Kennedy's ambassador to Moscow, cultivated a “close wartime liaison with a member of the Moscow ballet,” an aide recalled. The woman and her secret police connection “provided a pipeline through which [Thompson] could try out and receive suggestions that could not safely have been made officially.”9 Such coziness remained the exception. “We are living in a condition of total isolation” that was “terribly depressing,” Angus Ward, the U.S. consul in Vladivostok, complained to his Soviet counterpart, S. Gjukarev. When Russian guests begged off from his cocktail party, Ward felt “a slap in the face, which was still burning” a year later. Not just fear of the secret police, however, but also embarrassment at lacking the wherewithal to return the hospitality had kept some guests away. Unsympathetic to what he saw as Ward's “boredom,” Gjukarev advised the American to attend more concerts and theater.10 Like Ward, many Americans and Britons returned from Russia soured on cooperation with an alien system whose repression they had personally experienced or had seen up close.

Geoffrey Wilson, a Russian analyst in the British Foreign Office, pointed to the fallout from the “appalling isolation” of diplomats and journalists. “In all too many cases” their “whole attitude toward Russia is determined by the bitterness to which this [isolation] gives rise. Such [bitterness] is quickly sensed by the Russians and greatly resented.” The Russians were to blame for the vicious cycle. Nevertheless, British policy was skewed, Wilson worried, because experts on Russia found it difficult to retain “their capacity for balanced judgment.”11 In short, the personal could become the political—with harmful effects on diplomacy.

Though personal, these grievances were not petty because they linked to a key foreign policy objective. The right to associate with local people was the personal side of the Open Door policy. The logic of the Open Door entailed not just the prerogative to develop economic opportunities, but also the rights of individuals to move around, meet people, and build influence. The Kremlin's restrictions on contact violated emotionally resonant norms of individual opportunity and freedom. Americans and British regarded informal, personal contacts across borders as a means toward security. To the Russian government, however, whether under the czars or the commissars, the free competition of open contact threatened insecurity. Like their czarist predecessors, the Soviets resented uncontrolled contact with foreigners “as so much grit in the machine of government.”12 Conducting espionage in the West on a massive scale, the Soviets had a different set of practices for using personal contacts to gain influence in other nations.

For Kennan, Elbridge Durbrow, Bill Bullitt, and “Chip” Bohlen, the limits on contact were especially tough to take. They remembered the honeymoon of 1933–34, when Stalin, hoping for U.S. aid against Japan, had allowed Americans to associate freely with Kremlin officials, literary lions, and Bolshoi ballerinas. The lost paradise of those prepurge years would forever haunt these future Cold Warriors. (The memory of such contact also endured on the Moscow street. An extravagant wedding in the diplomatic community sparked the “persistent rumor that Harriman was marrying a ballerina.”13) The enforced isolation saddened Kennan, who loved immersing himself in Russian culture.14 For all the horrors the Nazis perpetrated, they, unlike the Soviets, allowed scope for both private property and private lives. Durbrow later recalled that officials from the U.S. embassies in Moscow and Berlin “used to get in awful arguments … whether Hitler was the worse dictator or Stalin. The Moscow boys always won.” He added that Stalin “made Hitler look like a little kindergarten kid.”15 On the very night that Durbrow left Moscow in 1937, the secret police arrested his longtime girlfriend Vera, an opera singer. In 1945, “Durby” again met up with Vera when she returned from the labor camp. Interviewed decades later, Durbrow cited Vera's fate as proof of Soviet iniquity. His personal pain colored—not determined but colored—his overall attitude. His anger and contempt informed his work in heading the state department's Eastern European bureau, in encouraging Harriman's hard-line stance in interpreting the Yalta accords on Poland, in spurring Kennan to write the Long Telegram, in replacing Kennan as number two in the Moscow embassy in 1946, and, appropriately enough, in cementing ties to South Vietnam while ambassador there in the 1950s.

U.S. and British archives are filled with anguished reports by diplomats and journalists whose loved ones, like Durbrow's Vera, suffered arrest, torture, and exile. One example can suffice. The prize-winning New York Times journalist Harrison Salisbury recalled that Americans and British married to Russian women “were living on the edge of catastrophe all the time.”16 The Russian wife of a British diplomat never left the embassy because she was wanted by the secret police. One day her brother called. Their mother was deathly ill and was begging to see her. British diplomats warned of a trap, but the woman insisted. Salisbury related that the wife was “taken in a British car by a British embassy attaché to the rendezvous point—they got out of the car, and a [Soviet] car whizzed up and she was grabbed and forced into the car—while the English watched, unable to interfere—and that was the last they saw of her.” Even four decades later, Salisbury again grew agitated in telling the story. Everyone “was outraged by this goddamn thing as any human being would be but the journalists and diplomats with Russian wives—to whom it might also happen, well, I mean, Jesus Christ—you can IMAGINE what it did to them! Aaah!”17 What leaps out of the page here is the screaming-out-loud intensity of the anger by the people on the scene, by the diplomats and reporters in Moscow, and by Salisbury, even many years later.

Intensity characterized a variety of emotional responses toward Russia. Interviewed decades later, Durbrow searched for the right words to explain what precisely had motivated Bullitt, Harriman, and other diplomats to turn one hundred and eighty degrees from eagerly anticipating close ties with the Soviets to bitterly opposing such cooperation. “The best way to talk about it,” he decided, was to think of “a disappointed lover.”“It's the disappointed lover,” he reaffirmed after further thought.18 Others also arrived at this analogy. In a novel based on his experience in Moscow, the playwright Sam Spewack wrote that U.S. diplomats “came with love, and left with fury.”19 Ward affirmed, “I love Russians.”20 Harriman in 1953 explained the entire Cold War as originating in Bullitt's failed mediation in 1919. Conflict began “when Wilson did not support Bill Bullitt's idea of making love to Lenin.”21 The choice of words here is striking. The discourse of falling in love or of making love suggests that, on one level, key American diplomats regarded this giant, distant country with its very different traditions and ideology as an exoticized object of desire. In their quest for intimacy they risked vulnerability. No wonder that Bullitt, Harriman, and others reacted with fury when feeling scorned. The exotic object of desire could easily morph into the exotic object of danger.

Russia's Mongol heritage and stretch across Asia, the Kremlin's tyranny, Stalin's Georgian birth, and the prominence of supposedly not-quite-European Jews among the early Bolsheviks fed notions of an “oriental despotism.” London officials referred to the Soviet ambassador's “merry Jewish-Mongolian eyes.”22 Inspecting the embassy in Moscow, a U.S. state department official worried that Kennan, who already suffered “poor health” and “moody spells,” might succumb to “the spell cast by the semi-oriental, semi-savage atmosphere” of Russia.23 Because Marxism-Leninism could appear as a rejection of normative Euro-American values, Soviet ideology was also racialized as “Asiatic.”“Othering” the Russians had a long history. But such representations grew more barbed as the Red Army blasted its way toward Berlin. The atrocities of Soviet soldiers avenged earlier German outrages, which the Americans and British had not witnessed and did not take fully into account. The behavior and appearance of soldiers, some of Siberian ethnicities and riding Siberian ponies, led those clustered around the kerosene heater to brand the rollback of Hitler's armies a “barbarian invasion of Europe.”24 This was a description whose emotional implications differed radically from FDR's talk of the Four Policemen.

Imperatives of pride also imperiled cooperation.25 In 1940–42, Axis military triumphs had humiliated in turn the British, Russians, and Americans. Each regarded its subsequent efforts as the key to victory. The British had fought the longest and for a frightful year all alone. The Soviets had suffered the most blood and damage and had waited three years for the second front. The Americans had donated tens of billions in supplies while massing forces in different theaters on opposite sides of the globe. As victory neared, even the liberal Robert Sherwood found it “difficult not to be an eagle-screaming, flag-waving chauvinist.”26 Molotov pounded his chest exclaiming “I am proud, proud, I tell you, to be the foreign minister of this great country!”27

Swollen pride impelled each of the Big Three nations to expect from the others overt gratitude and respect. Cultural differences in signaling respect magnified the tendency of each to see the other's strutting as evidence of disrespect and aggression. Alexandra Kollontay—a hero of the Bolshevik Revolution, a feminist theorist, and the Soviet ambassador to Sweden—described her nation's leaders as “naive, clumsy, and blundering. … They have no idea of when or why they give offense.” Yet they easily took offense. In triumph “they want the world to feel their strength and to pat them on the back for their success.” To those in London and Washington who feared the Soviets as a rising menace, Kollontay advised, “They are children, and must be treated as such.” Deep down Kremlin leaders knew “that they must cooperate.” Until these adolescents outgrew their “unruliness,” the Allies had to “practice patience and more patience.”28

Kollontay was describing, in effect, the Soviets' emotional disposition. We can think of “emotional disposition” as the tendency to respond to certain situations with a distinctive pattern of emotion-suffused rhetoric and actions. Emotional dispositions are conditioned by the prevailing cultural paradigms. It follows that different emotional patterns prevail in different cultures. Supposedly universal feelings such as anger or fear are interpreted and expressed differently across time and in different societies. Moreover supposedly simple emotions, such as anger, usually appear on closer examination as complex, hard-to-separate-out blends of emotions. My methodology here is to avoid getting bogged down in parsing the precise differences among Russian, American, and British understandings of, say, “pride.”29 I focus instead on the originating conditions for the expression of such emotions. Each nation's emotional disposition shaped the particular anxieties its leaders attached to their supposedly objective appraisals of international affairs. U.S. leaders, Roosevelt not included, tended to fret over whether others saw them as tough enough. The Soviets overcompensated for their status anxiety. The British, staggering to victory, seemed frantic to assert their authority. These trends and tropes were neither absolute nor exclusive. But like a computer operating system, such tendencies organized more or less inchoate concerns into a pattern of emotionalized political issues.

Roosevelt believed he understood something of Russian psychology. Before setting off for Tehran, he commented that Stalin's reluctance to travel far meant that he, Roosevelt, would have to journey 6,000 miles. He said, “Stalin believed that Russia had grown so “strong, that she can impose her will, & must be treated at least as an equal.” Unlike Truman and every other Cold-War President, Roosevelt did not, however, bristle at such arrogance. Instead, he looked deeper, seeing Stalin as “may be too anxious to prove his point. … Stalin suffered from an inferiority complex.”30 Roosevelt calculated that addressing the dictator's craving for respect could reap substantive gains. As Harry Hopkins remarked appreciatively at Tehran, FDR “had spent his life managing men.”31 Walter Lippmann later explained that “Roosevelt was a cynical man. What he thought he could do was outwit Stalin.”32

Yet playing the game of respect/humiliation could backfire, as actually happened after Roosevelt's death. General Deane interpreted FDR's self-confident gesture to Stalin as humiliating. He declared, “No single event of the war irritated me more than seeing the President of the United States lifted from wheel chair, to ship, to shore … in order to go halfway around the world as the only possible means of meeting Stalin.”33 According to Deane's emotional reasoning, in that wheelchair was not just Franklin D. Roosevelt, a man who wielded power quite effectively while sitting down. Rather, the seated man was “the President of the United States”—symbolically, the United States itself—and it was being humiliated by having to travel so far in such a visibly helpless condition to meet an imperious Stalin. What proved dangerous in such thinking was that Deane and Harriman convinced others that Washington had to respond to the supposed humiliations of the Roosevelt years by getting “tough” with the Russians.

Before the Cold War polarized nearly everything, even Stalin could acknowledge some lag in Russian culture. When Finns asked about his postwar agenda for the Soviet Union, he replied, “first to make the people more human and less like beasts by stilling their animal passions, their fears and lusts.”34 At Potsdam, he volunteered that Soviet generals “still lack breeding, and their manners are bad. Our people have a long way to go.”35 Such hints at a more open perspective faded with the alliance. By 1946, Stalin boasted that Soviet culture would soon be “a hundred times higher and better than any bourgeois system.”36 Fini any campaign to make the Soviet people “more human.”

In eight separate interviews done late in life, Molotov boasted that he and Stalin had avoided the humiliation of being made “fools” by the West.37 (Seven times he detailed how careful he and Stalin had been to stick to territorial “limits.”38) It “was my main task … to see that we would not be cheated,” Molotov stressed.39 He repeated, “It was hard to fool us.”40“Fools” merited not respect, but rather contempt. Fools lacked the intellectual and cultural capital to hold onto what they had earned. Fools, proletarians, and colonials could be exploited by those who manipulated the rules. Molotov worried that sophisticated Westerners could steal at the conference table what Russians had died for on the battlefield. “Our people don't like being treated like colonial people,” he blurted out to a British diplomat.41 Adamant about not looking—or being—fooled, cheated, or otherwise disrespected, the Soviets behaved in ways that Americans and British interpreted as arrogant, grasping, and lacking in respect.

Difference in others was more likely to be interpreted as evidence of malevolence or of inferiority by those Americans and British who assumed they embodied cultural and racial normativity. Told by Averell that they were dining at the Afghan embassy, Kathleen could not “remember if they smell or not.” She mused, “It certainly will be nice when the day comes when I'll once more be able to associate only with ‘white’ folk.”42 Despite her understanding that the Russians had waited a long time for the second front, she found their “enthusiasm” over Eisenhower's drive across France “childlike.”“This certainly is an unexplainable country,” she concluded.43

Whether the Anglo-Americans were viewing them as “unexplainable” or as unidimensional, the Soviets worried about such reductive stereotyping. In March 1945, a group of Soviet editors and foreign ministry officials attended a lunch hosted by the London Times. A Soviet editor stressed, “the last thing the Russians wanted was ‘exotic’ reporting on Russia.” He “kept on repeating his objections to ‘exoticism.’ ” By exoticism he seemed to mean exaggerating and making a spectacle out of either the good or the bad in Russia. Groping toward a concept that scholars decades later would term “orientalism,” the Soviet editors urged “giv[ing] a picture of Russia as she [really] is.”44 Similarly, when Stalin was asked what he would advise Americans, he replied, “Just judge the Soviet Union objectively. Do not either praise us or scold us. Just know us and judge us as we are and base your estimate of us upon facts and not rumors.”45 It remains unclear to what extent self-deception prevented Stalin from seeing the contradiction between this invitation to “know us” and the isolation his secret police imposed on foreigners trying to do just that. Highly emotional issues involving Poland undermined such tentative efforts to bridge the cultural gap.

It proved tragic that a mix of sui generis issues centered on Poland became the test case for cooperation at the critical juncture between war and peace. Poland hit home for each of the Big Three. Roosevelt needed votes from Polish-Americans. Stalin nursed both old and new grievances against the Poles. He understood that only a Poland yoked to “friendship”could overlook the Soviets' 1940 massacre of Polish officers in the Katyn forest. Only close ties would close the Polish gate to another invasion. The British had gone to war over Warsaw's independence. Over 100,000 Polish troops reinforced British forces. “Appeasing” Russia on Poland could cost Churchill the upcoming Parliamentary election. Britain's ambassador to the London Polish government framed the alternatives as “abetting a murder” by “selling the corpse of Poland to Russia” or asserting “moral authority.”46 Roosevelt cared not so much. “I am sick and tired of these people,” he muttered in complaining about the Polish ambassador's badgering him about restoring prewar borders. He added, “ I really think the 1941 frontiers are as just as any.”47

Raising the stakes was the Warsaw uprising. In August 1944, street fighters attacked the Nazi occupier. Supported by the London Polish government, they sought national independence. Evidence suggests that some of the fighters may have been been trained in the United States and parachuted in by the British.48 Resisters wielded whatever weapons they could scrounge. The Germans pounded them for three excruciating months as Americans and Britons looked on with horror. Stalin refused aid until nearly the end. Nor would he agree, despite appeals from Churchill and Roosevelt, to allow relief planes to refuel at the Poltava base in the Ukraine.49 Kennan later pinpointed this as the moment for a “political showdown with the Soviet leaders.” Harriman was so “shattered by the experience” that he suffered what Kathleen referred to as a near nervous breakdown.50

Making Stalin's veto especially frustrating was that Poltava was a hard-won American base. That “little patch of America in the middle of the Ukraine,” as its commander called it, shone as the proudest achievement of Harriman and Deane.51 Established in June 1944 for shuttle bombing of German targets, Poltava and the smaller facilities at Mirgorod and Piryatin seemed for few months a wedge that just might open the Soviet Union to Far Eastern air bases against Japan, postwar civil air agreements, and other contact. Deane, watching U.S. bombers land at their base in the Ukraine, felt “a thrill beyond description.” Kathleen Harriman observed that her father had never “been so thrilled by anything.”52 Such intensity of feeling perhaps played a role in coining its ultimate code name, FRANTIC. As the original name, BASEBALL, suggested, the project dovetailed with plans for a U.S.-led, postwar global system of air bases and civil air agreements.

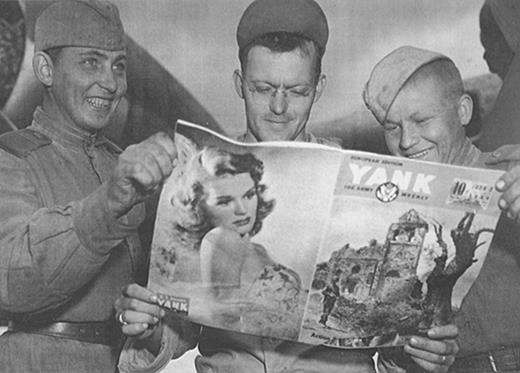

Cultural borrowing took off as the first planes landed. Airmen and technicians developed their own patois, and “after only a few weeks, some of the most amazing types of conversations could be heard between Russians and Americans,” an Army history noted.53 With Ukrainians sporting GI shirts and Americans displaying Ukrainian clothing, it was hard to “tell an American officer from a civilian,” a Soviet official complained.54 Copies of Life and Yank, permitted on the condition that they remain on base, soon circulated in nearby villages (see Figure 1). Like Harriman and other top officials who had invested emotions analogous to romantic “love” in their missions to Moscow, American pilots and mechanics nursed “a strange fascination for the Russian mission and a feeling … that its significance was far greater than its reputation.”55

Cultural borrowing took off with the establishment of the Poltava air base. Here two Red Army soldiers and an American GI appreciate the articles in one of the magazines that circulated on and off the base. Courtesy National Archives, Washington, DC.

Such commitments led to disappointment, especially as the secret police regarded contact as contamination. A visitor to the base observed that Americans “dated civilian girls, and plenty of them.”56 Nevertheless, GIs' “main gripe” was “interference by the Secret Political Police (NKVD) with their dates with girls.” Jealous Red Army soldiers helped enforce this “interference.” Undeterred, some Americans started “keeping lugers in girl friends' houses just in case.”57 Cultural insecurity probably spurred the objections to closer contact. A Ukrainian explained that during the two-year German occupation, she and other young women had seen that “the Germans were much more cultured and civilized than the Russians, [and] if these girls were allowed to see that the Americans were even more cultured and civilized than the Russians in their way of living, they obviously would prefer the Americans to the Russians.”58 From the Kremlin's perspective, unrestricted contact was also nervous-making because of the anti-Soviet guerrillas fighting not far away.59

In February-March 1945, Poltava figured in another operation that poked at Soviet control while tugging at American hearts: evacuating from Poland some 7,000 U.S. and British ex-POWs. The Red Army regarded all POWS as more likely cowards than heroes. They forced the ex-POWs to hitchhike and forage (i.e., pillage), much as Red Army soldiers often had to do. In contrast, many Poles went all out for these strangers, partly in hope that gratitude in Washington and London might rescue them from Moscow. The Soviets swept the ex-POWS toward the port of Odessa, from which nearly all were evacuated by V-E day.60 Americans—who have mythicized and ennobled captives since the days of Mary Rowlandson and the Indians—were appalled at Soviet callousness. Harriman and Deane planned for U.S. planes based at Poltava to criss-cross Poland evacuating ex-POWS. Roosevelt urged Stalin to comply. Such rescue flights would give Poltava a new rationale, since German retreats had ended the need for shuttle bombing.

Stalin saw the rescue plan as yet further meddling in his sphere. As he knew or suspected, British Special Operations were already smuggling anti-Soviet agents in and out of Poland disguised as Allied ex-POWs.61 Harriman and Deane were pressing for a new air base in Soviet-occupied Hungary. Despite his resentment of the Soviets, Admiral Ernest Archer of the British military mission in Moscow was appalled at London's brazenness in getting into Soviet-occupied Poland. His government had “kept at the Russians for months until eventually permission was given to inspect an acoustic torpedo” from a U-250 boat at Gdynia. He added that “it came as something of a shock to hear from the [inspection] party that the visit was really only paid for political reasons, as plenty of information had become available from other sources. The same, I imagine, is true of many other desired visits or facilities, such as bomb damage assessment and the like.”62 Although such intelligence efforts were dwarfed by Soviet operations in Britain and America, a cloak-and-dagger contest was already under way.

Emotional reasoning linked oppression of Poland and oppression of Americans. As Deane's aide put it, “the Soviet attitude toward liberated American prisoners is the same as the Soviet attitude toward the countries they have liberated. Prisoners are spoils of war … They maybe be robbed, starved, and abused and no one has the right to question such treatment.”63 Deane would recall the quashing of the air rescue as “my darkest days in Russia.”64 Harriman cabled Roosevelt: “I am outraged” at the Russians.65 He warned FDR that when word of the POW story got out “there will be great and lasting resentment on the part of the American people” (see Figure 2).66

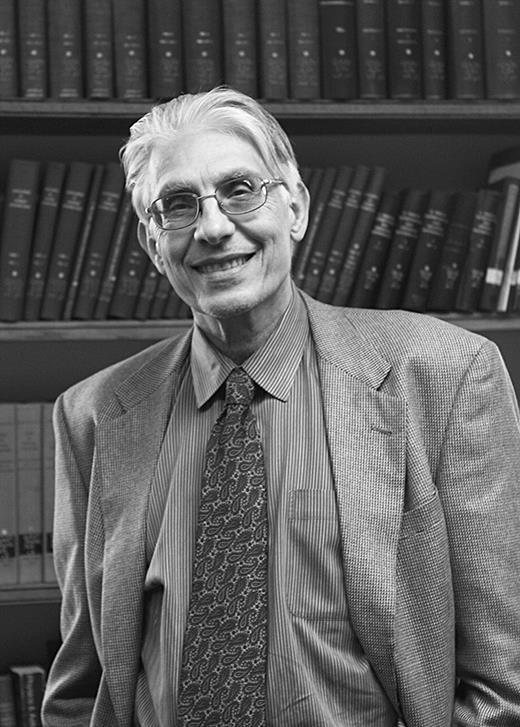

Harriman and Stalin increasingly had difficulty seeing eye to eye. Bohlen looks on grimly in this Yalta photograph. Courtesy Library of Congress. My thanks to Douglas Snyder for help in obtaining this image.

Though angry, the president refused to escalate the dispute. Unlike Harriman, Roosevelt remained committed to pursuing postwar cooperation. The president believed he had “worked it out”: by the spring of 1944 he had shifted his eating, smoking, and work habits to a regimen that he claimed would enable him to conserve strength and survive a fourth term.67

In his March 1, 1945 report to Congress on Yalta, FDR juggled two aims: first, not losing political support from the many Americans who cherished the Atlantic Charter's dream of universal democracy and the open door and second, preparing Americans for the reality of a more ambiguous world order, at least during the postwar transition. Four years earlier, Roosevelt had turned to Harry Hopkins to help craft another difficult pitch, Lend Lease aid. But their partnership had not survived Yalta. FDR had never forgiven Hopkins's December 1943 decision to move out of the White House in order to save his marriage and his health. The president felt abandoned.68 Though personal relations remained cool, Hopkins had resumed working in the White House in late 1944. Sent ahead to prepare for the February summit, he had arrived at Yalta debilitated by dysentery aggravated by immoderate drinking and eating. After the conference, instead of helping draft the report to Congress on the voyage home, Harry flew most of the way back. Roosevelt lapsed into procrastination. Speech writer Sam Rosenman would later complain that he “couldn't get [Roosevelt] to work. … He would sit up on the top deck with his daughter Anna [Boettiger] most of the day.”69 Determined to rest and unsure how to explain Yalta, FDR dawdled until the day before the Quincy docked. Desperate, Rosenman worked from a memorandum from Bohlen and input from Admiral William Leahy and Boettiger.

The president continued procrastinating until the very moment he sat down before Congress. He departed from his prepared text with lengthy, significant ad libs. Aside from the statement that he was sitting in order to avoid “having to carry about ten pounds of steel” braces, the most enduring sentence of the speech was a distortion: Yalta “spell[s] the end of the system of unilateral action, exclusive alliances, spheres of influence, balances of power, and all the other expedients which have been tried for centuries—and have failed.” To the contrary, Yalta had fostered tacit balance of power deals for a Soviet sphere in Eastern Europe, a British sphere in Western Europe and in the empire, and a U.S. sphere in Latin America, Japan, and perhaps China. How open those spheres would be remained uncertain.

An inelegant collage of contradictions, Roosevelt's March 1 speech nevertheless ranks as one of his greatest. In articulating his less mediated thoughts, he more accurately depicted the ambiguity, ambivalence, and accommodations of Yalta. He tried to tone down the already rampant triumphalism about America's victory. Discerning as ever, Lippmann caught the big picture. “Not for a long time, if ever before, has he talked so easily with the Congress and the people, rather than to them, and down to them.”70 Roosevelt warned that despite the power of the United States, the nation could not dictate the peace. He tried to lower expectations. He ad libbed a qualifier to his claim about the end of spheres of influence so that it began, Yalta “ought to spell” the end rather than “it spells” the end. A world order based on the Atlantic Charter would come about only gradually. The peace “cannot be, what some people think, a structure of complete perfection at first.” In talking about “interim governments,” he added to the written text the caution that free elections would only come “thereafter.”

To a nation accustomed to simplifying foreign issues and universalizing the American experience, the president ad libbed that postwar issues were “very special problems. We over here find it difficult to understand the ramifications of many of these problems in foreign lands, but we are trying to.” In a long addition he instructed Americans on Russia's case for Poland's new borders. Alluding to the dispute between the Lublin and London Poles, he said that the government in Warsaw would not immediately, but rather “ultimately” be selected by the Polish people. Yalta “was a compromise,” he stressed. To give a sense of how the Soviets felt, he described the Germans' “terrible destruction” in the Crimea. Speaking seven weeks before President Truman would say that the Russians could go to hell if they objected to America's program, Roosevelt emphasized “give-and-take compromise. The United States will not always have its way a hundred percent—nor will Russia nor Great Britain. We shall not always have ideal answers to complicated international problems, even though we are determined continuously to strive toward that ideal.” Roosevelt—who considered himself the first diva while complaining about the “many prima donnas in this world”—was tragically remiss in not explaining his off-the-cuff remarks to the vice president.71

FDR also seemed prepared to tell Stalin about the atomic bomb project. At Yalta he had allowed Churchill to dissuade him.72 By March 9, he said, “the time had come to tell [the Russians] how far the developments had gone,” even though “Churchill was opposed to doing this.”73

Harriman and his boss disagreed until the latter's death. Roosevelt, seeking to end his spat with Stalin over the Italian surrender negotiations in Berne, cabled the dictator: “in any event, there must not be mutual distrust, and minor misunderstandings of this character should not arise in the future.”74 Instead of delivering the telegram, the ambassador, astoundingly, tried to change it. He urged the president to eliminate the word “minor” because “the misunderstanding appeared to me to be of a major character.”75 FDR insisted: “I do not wish to delete the word ‘minor’ as it is my desire to consider the … misunderstanding a minor incident.”76 Two aspects here bear emphasis. First, Roosevelt understood that a dispute he considered minor might remain so, and a dispute he considered major would become so. Second, an angry Harriman was so intent on “toughening” U.S. policy that he risked his ties to the president.

Denied permission to come to Washington, Harriman on April 10 wrote an extraordinary telegram. He made the emotionally explosive, difficult-to-dislodge argument that the policy of cooperating with Stalin had “been influenced by a sense of fear.” Charging that a policy was influenced by fear was, in effect, deliberately delegitimating that policy. The draft of this telegram offers evidence of how the ambassador tried to smear Roosevelt's policy by describing it as based on cowardly fear even though he had little proof of such fear. At first, he seemed unsure how to argue his far-fetched proposition. Exactly what did the United States fear? In the draft, he first wrote that U.S. decisions “have been influenced by a sense of fear of the Soviet Union.” He evidently then decided, however, that it would be difficult to convince the president that he, Roosevelt, feared the Soviet Union. So Harriman scratched out “fear of the Soviet Union,” and wrote the vaguer formulation “fear of it.” Then he crossed that out and settled for the still vaguer, but even harder to refute, formulation that decisions were “influenced by a sense of fear on our part.” Harriman then repeated the word “fear” five times by representing policy concerns as cowardly “fears.”77 He used the word “insult” five times in detailing the “almost daily,”“outrageous” indignities he was suffering in Moscow.78

After Roosevelt died on April 12, Harriman got permission to brief the new president. Rushing to Washington, his plane knocked seven hours off the previous flight record. In the hubbub, the Soviets neglected to check departure documents. Ever mindful of the personal contact issue, those on board rued the missed chance to smuggle out some Soviet wives.79 Agitated, the ambassador displayed a nervous tic in his eye. To Durbrow he appeared “just steaming.”80 Meiklejohn believed that U.S. policy toward Russia was “letting a Frankenstein loose upon Europe. … Until that Frankenstein is disposed of, there will be no peace in the world.”81 Also aboard was British ambassador Clark Kerr, who described Harriman as having careened from “high elation” to the “deepest melancholia. … His melancholia had turned into something like hate, and he was determined to advise his government to waste no more time on the effort to understand and to cooperate with the Russians.”82 Once in Washington, Harriman hit it off immediately with Truman, himself anxious about whether he measured up to his daunting job.83

Arguably, it was the anger at the Soviets over the Warsaw uprising, anger over the ex-POWs, over the brutal domination of Poland—anger also building from frustration at the forced isolation and stoked by Soviet arrogance in victory—arguably, it was such anger that blinded Harriman and his advisers to the weakness of their negotiating position on implementing the Yalta agreement on Poland. While in the United States in April and May, Harriman would exercise enormous influence with Truman administration officials, legislators, and journalists. With his on-the-scene authority, the ambassador argued that Soviet insistence on the dominance of the pro-Moscow Lublin Poles violated Yalta. The Yalta accord was ambiguous.

But three authoritative American and British sources independently agreed that the Soviets had the stronger case in arguing for retaining the Lublin government and merely adding other Polish elements. Clark Kerr confided to Lippmann that following Yalta, London officials had “overruled” him and “asked for an interpretation of the Crimean agreement which made the problem insoluble.”84 Frank Roberts, who had worked with the London Polish government and who would write his own “long telegram” in 1946, reported on first arriving in Moscow that the Yalta agreement “was interpreted not only by the Russians but also by … independent and by no means pro-Russian journalists here as being a Russian victory in the sense that we, for the first time, completely ignored the Polish Government in London and went some way towards recognition” of the Lublin government. “In so far as we want a new deal, and, in fact, the elimination or subordination of the [Lublin] group, we are fighting for something which the Russians … are not prepared to concede.”85 Finally, Jimmy Byrnes, who was at Yalta, acknowledged in June 1945 “that there was no question as to what the spirit of the agreement was. There was no intent that a new government was to be created independent of the Lublin government. The basis was to be the Lublin government.”86 Even though many of Roosevelt's March-April cables regarding Poland were drafted by his more hard-line advisers, particularly Leahy and Bohlen, they recognized the primacy of the Lublin Poles to a degree that neither Churchill nor Harriman and Truman would accept.87

What Clark Kerr characterized as Harriman's “hate” influenced four discourse-changing conversations in Washington and in San Francisco. First Harriman spoke with Truman alone, thereafter with Truman and other advisers, and then the president confronted Molotov. A week later, America's top “Soviet expert” briefed journalists at the San Francisco conference. The talks framed an argument that made it seem not just permissible, but also necessary and realistic to regard the Soviets as more foe than friend. Roosevelt almost certainly would have resisted this discursive revolution and the attitudes and policies flowing from it. In tone and language, FDR's report on Yalta had sought to rein in America's appetite for triumphalism, exceptionalism, and railing at an evil “other.” Harriman and Truman rejected such emotional restraint. By emphasizing America's global power and righteousness, they fed the vicious circle of pride and anxiety that would soon destroy the wartime alliance.

Meeting with the new president on April 20, Harriman tossed the fear bomb. He said that FDR's policy had rested on shameful fear. Proud and insecure, Truman quickly interjected that “he was not in any sense afraid of the Russians.” Harriman then undercut the rationale for the alliance by presenting as a fatal contradiction that which Roosevelt had regarded as a fact of life. During the postwar transition Moscow would seek both cooperation with its allies and dominance over its neighbors. The ambassador made still another alarmist claim: the Soviets lacked any sense of limits. Therefore getting along with Russia would require the United States to endure a humiliating passivity. He concluded with a flatly wrong prediction. Because the Kremlin “did not wish to break with the United States … we had nothing to lose by standing firm.”88

Roosevelt, understanding that cultural differences could doom the alliance, played them down. Harriman played them up. Indeed, he inflated them. To Truman, who liked reading about Genghis Khan, Harriman repeated the kerosene-stove comment that the armies rolling back the Nazis amounted to a “barbarian invasion of Europe.” Bohlen liked the zing. While his minutes paraphrased the rest of the conversation, this was the only phrase to appear in quotation marks.89 Deane meanwhile made similar arguments to Pentagon officials.90

On April 23, Truman canvassed advisers before meeting with Molotov. He set the tone by declaring that the Russians “could go to hell” if they did not attend the San Francisco conference. Harriman and Deane reconceptualized the problem of Poland so as to directly and morally involve the United States. “The real issue,” he insisted, “was whether we were to be a party to a program of Soviet domination of Poland.”91 According to this provocative formulation, unless Washington escalated Poland into a crisis, U.S. leaders themselves would become “a party” to Moscow's brutal domination—perpetrators rather than bystanders. In other words, Washington had to assume responsibility for freedom up to the very border of its victorious, touchy, and insistent ally. Or else Polish blood would stain American hands. Such dangerous reasoning greased the slide from the Atlantic Charter to the Cold War.

In the meeting with Truman's advisers, Deane's insinuation was equally explosive: “If we were afraid of the Russians, we would get nowhere.” Washington had to act in order to regain Moscow's respect. Charges of being afraid were an effective slur: easy to make, difficult to disprove. Once someone raised the issue of fear, it became harder to argue against confronting the Russians. Even readier to scuttle the alliance was Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, who argued that if the Russians did not retreat, “we had better have a show down with them now than later.” Leahy, who had stood at Roosevelt's side at Yalta, informed the group that the agreement on Poland “was susceptible to two interpretations.” Nevertheless, he also insisted on “a free and independent Poland.”92

In keeping with the customary discourse of official minutes, Bohlen's record flattened the emotional tone of the talk. The meeting was actually, however, quite emotional as a participant soon informed Felix Frankfurter. There was “much ‘banging of fists’ on the table in arguing that it was ‘high time’ to take a ‘tough line’ with Russia.” Harsh talk was “the only language the Russians could understand.” Stalin had sent an “insulting” note to Roosevelt.93 Such proto-Cold War, masculine-tough-guy renderings implicitly faulted the late president. Almost in caricature they were implying that the wheelchair-bound Roosevelt may have been unwilling or unable to stand up to the Russians, but the new leadership was eager to prove its grit.

Only Stimson and General Marshall sounded caution. Stimson worried that emotional thinking was distorting perceptions of national interest. He had noted in his diary that Harriman and Deane “have been suffering personally from the Russians' behavior on minor matters.”“Influenced by their past bad treatment,” they were arguing “for strong words by [the] President.”94 Stimson did not see U.S. vital interests as extending deep into Eastern Europe, especially since “25 years ago all of Poland had been Russian.”95 Truman, however, ignored Stimson's skepticism.

Molotov was meanwhile lunching with Joe Davies. Molotov told Davies that in the Kremlin the president's death weighed as “a great loss and an irreparable one. … Stalin and Roosevelt understood each other.” Despite post-Yalta tensions, Stalin had believed that “any difference could always be adjusted through mutual discussions and tolerance, for there was a will to achieve cooperation.” Davies urged Molotov to “specifically ask the President” not to commit himself on the Polish government “until he has heard all the facts and the Soviet point of view.” A poker buddy of Truman, Davies feared “the principle danger … would come from a ‘snap judgment.’ ”96

In meeting with Molotov Truman lectured rather than listened. Echoing Harriman's provocative new formulation, he warned that America “could not agree to be a party” to Soviet domination of Poland. Molotov tried to make two points on how the Big Three had managed to function. First, despite their differences, “the three Governments had been able to find a common language and decide questions by agreement.” Second, they “had dealt as equal parties, and there had been no case where one or two of the three had attempted to impose their will on another.” Truman repeated that the Yalta agreement on Poland was clear cut. He seemed undeterred by Leahy's admission that Yalta was open to two interpretations. He probably did not know, and may not have cared about, the views of Clark Kerr and Roberts. It remains a puzzle precisely what Byrnes did and did not tell Truman about Yalta. In any case, the president told Molotov that Stalin was violating the agreement. Molotov snapped that unlike other allies, the Soviets had stuck by Yalta. Moreover, Poland loomed on their border, and they would not tolerate anti-Russians in Warsaw. Truman interrupted that there was no use discussing that further. When Molotov brought up the Far Eastern war, where the Red Army would be needed, Truman cut him off, saying, “That will be all, Mr. Molotov.”97 Durbrow, who observed the Russian leave, would later recall, “I've never seen a man come out more ashen in my life.”98 As Davies had feared, his friend had reached a “snap judgment” after refusing to consider the Russian viewpoint.

Bohlen would recall the conversation as, quite literally, a discursive break: “probably the first sharp words uttered during the war by an American President to a high Soviet official.”99 Memories of an exciting event can become indelible. Decades later Bohlen could still exclaim, “How I enjoyed translating Truman's sentences!” Perhaps on some level he also enjoyed avenging what he and other young American diplomats had lost in the post-1934 purges. Rather than editing the emotions out of his minutes, Bohlen highlighted them. He probably realized that his new boss would fancy a record of himself talking tough. Afterward, Truman bragged, “I gave it to him straight. I let him have it. It was straight one-two to the jaw.” Yet the champ remained insecure. “Did I do right?” he asked.100

A week later in San Francisco, Harriman invited a dozen top journalists to his apartment. He ominously announced that “on long range politics there is an irreconcilable difference” between the Soviet Union and the Western allies. He used emotion-evoking words that had circulated around Meiklejohn's stove. Kennan would employ similar rhetoric in his 1946 long telegram and in his 1947 “Mr. X” article. The ambassador blamed everything on the Kremlin's “Marxian penetration.” The phrase suggested assault that was simultaneously ideological, political, and sexual. The trope caught on. The first question posed by a journalist asked the difference “between the Russian policy of penetration, as you put it, and Nazi policy.” Repeating the word “penetrate,” Harriman answered that the Soviets probably did not intend military aggression. Other journalists also picked up on the emotional phrase. While some journalists bought this scare argument, others grew furious. Lippmann and Raymond Swing, a popular radio announcer, stormed out in protest. When another reported asked “has our policy changed since Roosevelt?” Harriman nervously backtracked. The reporter pressed him: “But it is obvious there IS A CHANGE.”101 Once back in Moscow, the ambassador continued efforts at “indoctrinating” visiting congressmen and senators, Meiklejohn noted.102

Harriman helped establish the long-lasting discursive frame for U.S. Cold War policy. His emotional language amplified the impact of his authority as a Soviet expert. Policy and opinion makers got the message: it was normal and realistic to refer to the Soviets as dangerous aliens with whom there was an “irreconcilable” ideological conflict. This discursive attack on the alliance persisted even when political relations warmed, as they did on and off for the remainder of 1945. Truman never made a splashy statement to stem the tide. Fanning fears proved easier than quieting them. Donald Nelson, a wartime production administrator who had found Stalin eager to expand trade, now feared war. Nelson “put the responsibility chiefly on Averell Harriman.”103 Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson faulted his friend's attitude and tactics. “Averell is very ferocious about the Rouskis. … He seems in favor of any stick to beat them with.” Nevertheless, Acheson accepted the ambassador's argument that the Russians “are behaving badly.”104 Although Harriman and his cohort sought not armed conflict, but rather a calibrated policy of containing Russia and building alliances in the West, their pushing for a tougher stance fed public fears of war.

After Harriman's talks in April-May, it became more customary to talk about the Soviets not as fellow world policemen as Roosevelt had often depicted them, but rather as international criminals. Parallel changes were propelled by Churchill and others in London. British military officials, some already branding Russia the enemy, were emboldened by Churchill's request for a contingency plan to attack the Soviet Union in July.105 Anti-Soviet stalwarts in the state department and other hardliners, such as Forrestal, did not need Harriman to turn them against FDR's priority of getting along with Moscow. The ambassador had his greatest impact on Truman, particularly in claiming that Roosevelt's policy had reflected cowardly “fear” of the Soviets. This argument touched a nerve with the insecure new president, anxious to show he feared neither Stalin nor his new job. For all Truman's public praise of Roosevelt, he liked to think that he was in certain respects a better president because he could act decisively. Harriman was not alone in driving the discursive shift. Yet he voiced the authority of firsthand experience in dealing with Stalin.

The Soviets did do terrible things. Harriman and others were justified in their anger and disgust at the isolation, at the rape and pillage by Red Army soldiers, at Stalin's co-responsibility for the crushing of the Warsaw uprising, at the callousness toward the liberated POWs, and at the oppression of Poland. Nevertheless, personally and morally satisfying expressions of anger produced a rhetoric in which measured, judicious strategic thinking was, tragically, blinkered. Despite the egregiousness of Soviet actions, these actions—and the jabs and counterjabs that followed—did not justify the Cold War. The costs of that conflict proved far higher: deadly proxy wars, the atomic arms race (the full price of which we perhaps have not yet paid), the militarizing of U.S. society, and, probably, the deepening and prolonging of Soviet oppression. It was unfortunate that Roosevelt died and that Harriman, Kennan, and company came to the fore at such a critical juncture between war and peace. Roosevelt had planned for the Big Three jointly to manage the gradual transition to a stable, more multilateral world. Differences that might have been papered over during such a transition instead blew up into an ideologically fueled, tit-for-tat conflict.

The spring of 1945 was a critical juncture in history—like August 1914, November 1989, or September 2001. At such turning points, the contingency of personalities, feelings, and cultural assumptions can propel massive events with dangerous (or positive) momentum. Once the discursive shift became public, the kind of quiet deals formerly reached by the Big Three became unworkable in the glare of domestic politics. Rhetoric about the Soviet threat and the vicious spiral of fear and disrespect opened the way for far-Right anti-Communists who within a few years were labeling even Truman an appeaser. The change from Roosevelt to Truman occurred on many levels, not least in a shift from emotional control to a venting and exaggerating of differences that would explode the wartime alliance.

When Kennan arrived in Moscow in 1933 and Harriman in 1943, they were each excited about becoming a key go-between linking America and Russia. Bitterly disappointed, they became advocates of a tougher policy—but they did so expecting that this pressure would force the Soviets to yield. Ironically, decades before Russia did open up, both Kennan and Harriman had reversed their earlier tough stances and had become voices for reengaging Moscow. Harriman went so far as to conclude that “FDR was basically right in thinking he could make progress by personal relations with Stalin. … The Russians were utterly convinced that the change came as a result of the shift from Roosevelt to Truman.”106 Harriman bore much of the responsibility for that tragic change.

Finally, that stove: The grumbling around the Spaso house hot stove sparked rhetorical incendiaries that burned for decades. As a nation, we're still, in effect, grumbling around the stove about a world that we cannot remake in our image.

Footnotes

Robert P. Meiklejohn diary, February 23–25, 1945, box 211, W. Averell Harriman Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Meiklejohn diary, August 18, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

For an account that minimizes the shift between presidents, see Wilson D. Miscamble, From Roosevelt to Truman (New York, 2007). Vladimir Pechatnov, Stalin, Ruzvel't, Trumen (Moscow, 2006) is based on both Russian and U.S. archival sources. See recent assessments in David B. Woolner, Warren F. Kimball, and David Reynolds, eds., FDR's World: War, Peace, and Legacies (New York, 2008).

Meiklejohn diary, March 17, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

Ibid.

Meiklejohn diary, March 25, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

Meiklejohn diary, October 4, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

Kemp Tolley, Caviar and Commissars (Annapolis, MD, 1983), 64.

S. Gjukarev diary, March 7, 1944 (Archive of Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation, Moscow (hereafter AVPRF), f., op. 28, pap. 155, ll. 24–26.

Minute by Geoffrey Wilson, August 4, 1944, F. O. 371/43305, National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

“Survey of Contact,” July 2, 1944, F. O. 371/43305.

Kathleen to Averell, May 4, 1946, box 5, Harriman Papers.

Reminiscences of Elbridge Durbrow (1981), pp. 76, 78, Columbia University Oral History Research Office Collection, New York (hereafter CUOHROC).

Whitman Bassow interview with Harrison Salisbury, July 6, 1985, box 3, Whitman Bassow Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Bassow interview with Salisbury, July 6, 1985, box 3, Bassow Papers.

Reminiscences of Durbrow, pp. 69, 74, CUOHROC.

Samuel Spewack, The Busy Busy People (Boston, 1948), 144.

S. Gjukarev diary, March 7, 1944, AVPRF, f. op. 28, pap. 155, ll. 24–26.

“Off the Record Discussion of the Origins of the Cold War,” May 31, 1967, box 869, Harriman Papers.

Clark Kerr to Foreign Office, April 6, 1945, F. O. 371/47881; Roberts to Bevin, “Report on Leading Personalities in the Soviet Union,” May 22, 1946, F. O. 371/56871.

J. K. Huddle, “Personnel Conditions at the Moscow Embassy,” April 17, 1937, box 102, Inspection Reports on Foreign Service Posts, Record Group (RG) 59, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Meiklejohn diary, March 17, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

For an introduction to the theory, see Gabriele Taylor, Pride, Shame, and Guilt: Emotions of Self-Assessment (Oxford, 1985); William Ian Miller, Humiliation (Ithaca, NY, 1993); Robert A. Nye, Masculinity and Male Codes of Honor in Modern France (New York, 1993).

Robert Sherwood to Hopkins, April 4, 1945, box 4, series III, Harry L. Hopkins Papers, Georgetown University, Washington, DC.

Clark Kerr to Anthony Eden, August 31, 1944, N5598/183/38, F. O. 371/43336.

Clark Kerr to Foreign Office, April 6, 1945, F. O. 371/47881. Harriman alluded to his talk with Kollontay in his unsent telegram of April 10, 1945, box 178, Harriman Papers.

For an introduction, see Jerome Kagan, What Is Emotion? (New Haven, CT, 2007); Robert C. Solomon, ed., What Is an Emotion (New York, 2003); Amelie Oksenberg Rorty, ed., Explaining Emotions (Berkeley, CA, 1980); Richard Immerman, “Psychology,” in Michael J. Hogan and Thomas G. Paterson, eds., Explaining American Foreign Relations History (New York, 2004), 103–22.

Geoffrey C. Ward, ed., Closest Companion (Boston, 1995), 253 (emphasis in original).

Lord Moran, Churchill at War 1940–45 (New York, 2002), 162.

Reminiscences of Walter Lippmann, p. 217, CUOHROC.

John R. Deane, The Strange Alliance (New York, 1947), 160.

Frank Roberts to Foreign Office, October 19, 1945, F. O. 371/47807.

A. H. Birse, Memoirs of an Interpreter (New York, 1967), 209.

Geoffrey Roberts, Stalin's Wars (New Haven, CT, 2006), 331, 333.

Albert Resis, ed., Molotov Remembers (Chicago, 1993), 11, 19, 23, 44, 53, 55, 69, 77.

Ibid., 8, 52, 59, 65, 66, 73, 74.

Ibid., 53.

Ibid., 69.

Molotov conversation with John Balfour, December 13, 1943, AVPRF, f. Secretariat V. M. Molotov'a op. 5, pap. 17, ll. 57.

Kathleen to Mary, February 16, 1944, box 171, Harriman Papers. Smells can jolt thinking. While sights, sounds, and tactile sensations are first processed by the brain's thalamus, smells can bypass the thalamus to activate the cortex directly. See Kagan, What Is Emotions?, 45. The salient olfactory dimension of the Soviet capital hit Kathleen on her arrival: “Moscow makes an impression on you—[a] mixture of dank smells.” She added, “It's a town where foreigners get depressed, because they can't become part of the town.” (Kathleen to Pamela Churchill, [November 1943], box 170 Harriman Papers.) My thanks to Sherry Zane for sharing this document. I have benefited from conversation with Andy Rotter, who is writing on the connections between the senses and international relations.

Kathleen to Mary, August 30, 1944, box 173, Harriman Papers.

Frank Roberts to Christopher F. A. Warner, March 14, 1945, F. O. 371/47934. An article in Bolshevik criticized a tendency of the British to describe as an “ ‘enigma’ anything which will not fit into their conception of things.” D. Zaslavski, cited in minute by George Hill, April 18, 1945, F. O. 371/47853.

“Stalin Voices Aim for Amity and Aid of U.S. in the Peace,”New York Times, October 1, 1945, copy in box 206, Harriman Papers.

Owen O'Malley to Eden, January 22, 1944, F. O. 954/20.

Lt. Miles, “The President at Home,” December 20, 1943, F. O. 371/38516, PRO. The visit ended on Tuesday, November 2, 1943.

Jonathan Walker, Poland Alone: Britain, SOE and the Collapse of the Polish Resistance, 1944 (Stroud, Gloucestershire, 2008), 204–61.

Mark J. Conversino, Fighting with the Soviets, (Lawrence, KS, 1997), 67.

Frank Costigliola, “ ‘I Had Come as a Friend’: Emotion, Culture, and Ambiguity in the Formation of the Cold War, 1943–45,”Cold War History 1 (August 2000): 116–17.

William R. Kaluta, History of Eastern Command, U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe (1945), Reel B5122/1473, p. 57, U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. GI pranksters primed Russian soldiers to greet American officers with “Good morning, you lousy S.O.B.” Ibid., 58.

Conversino, Fighting with the Soviets, 182.

Kaluta, Eastern Command, 66. Even as the practical utility of Poltava was declining, commanders worried that closing it “would deprive the United States Army of any base whatsoever on Russian soil.” Deane to Spaatz, March 4, 1945, box 65, entry 311, RG 334, National Archives.

Tolley, Caviar and Commissars, 202.

Kaluta, Eastern Command, 146.

Kaluta, Eastern Command, 144.

See Jeffrey Burds, Borderland Wars: Stalin's War against “Fifth Columnists” on the Soviet Periphery, 1937–1953, forthcoming.

SOE memorandum, “Answers to Questions”[no date but 1945], HS4/211, National Archives, Kew.

Archer to Rushbrooke, April 16, 1945, ADM223/249, National Archives, Kew.

Lt. Col. James D. Wilmeth, “Report on a Visit to Lublin, Poland February 27–March 28 1945,” box 22, entry 319, RG 334, National Archives, Washington, DC.

Deane, Strange Alliance, 182.

Harriman to the President, March 8, 1945, box 34, Map Room files (hereafter MR), Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library (hereafter FDRL), Hyde Park, New York.

Ibid.

Marquis Childs, “Report of a Conversation with President Roosevelt on Friday, April 7, 1944,” box 4, Marquis Childs Papers, Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison, Wisconsin. For discussion of FDR's health, see

Costigliola, “Broken Circle,” 694–707.

Samuel I. Rosenman oral history, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library, Independence, Missouri.

Walter Lippmann, Today and Tomorrow, March 3, 1945.

“Address of the President to the Joint Session of the Congress, March 1, 1945,” box 86, Master Speech File, FDRL. On the drafting of the speech, see undated memorandum by Rosenman, “Yalta Speech,” box 18, Samuel I. Rosenman Papers, FDRL; Rosenman, Working with Roosevelt, 526–30.

Martin J. Sherwin, A World Destroyed (New York, 1977), 290.

William Lyon Mackenzie King diary, March 9, 1945, http://canadaonline.about.com/cs/primeminister/a/kingdiaries.htm.

Stalin's Correspondence with Roosevelt and Truman 1941–1945 (New York, 1965), 214.

Harriman to the President, April 12, 1945, box 178, Harriman Papers.

Roosevelt to Harriman, April 12, 1945, box 178, Harriman Papers.

Harriman to Secretary of State [unsent], April 10, 1945, box 178, Harriman Papers.

Pentagon generals, however, examined a list of similar complaints from Deane and judged them “irritating” but “of relatively minor moment.”

Meiklejohn diary, April 15–17, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

Reminiscences of Durbrow, 65, CUOHROC.

Meiklejohn diary, April 9, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

Archibald Clark Kerr to Christopher Warner, June 21, 1945, F. O. 371/47862.

For Truman's concerns about assuming the presidency and about the connection between height and presidential greatness, see Robert H. Ferrell, ed., Off the Record: The Private Papers of Harry S. Truman (New York, 1980), 16; Margaret Truman, ed., Where the Buck Stops (New York, 1989), 77–79. On the activities of Harriman and Deane in Washington, see Clemens, “Reversal of Cooperation,” 293–303.

Lippmann to Hans Kohn, May 30, 1945, box 82, Walter Lippmann Papers, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Frank K. Roberts to Christopher F. A. Warner, March 14, 1945, F. O. 371/47934.

Joseph E. Davies diary, June 6, 1945, box 17, Joseph E. Davies Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Though Davies sympathized with the Soviets, historians have not questioned the veracity of his diary. The entry cited here is an original, not one of the reworked passages that Davies did in the early 1950s.

Warren F. Kimball, ed., Churchill & Roosevelt (Princeton, New Jersey, 1984) 3: 593–97.

U.S. State Department, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1945 (Washington, DC, 1967), 5: 232 (hereafter FRUS).

Ibid.

Clemens, “Reversal of Cooperation,” 293–303.

FRUS, 1945, 5: 253.

FRUS, 1945, 5: 253–55.

Davies conversation with Frankfurter in Davies journal, May 13, 945, box 16, Davies Papers.

Stimson diary, April 23, 1945, Stimson Papers, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

FRUS, 1945, 5: 253–54.

Davies journal, April 23, 30, 1945, box 16, Davies Papers.

Charles E. Bohlen, Witness to History 1929–1969 (New York, 1973), 213.

Reminiscences of Durbrow, 70, CUOHROC.

Bohlen, Witness to History, 213.

Davies journal, April 30, 1945, box 16, Davies Papers. The quotation is from Davies's notes after his talk with Truman.

Clark Kerr sent a transcript of the exchange to London. Archibald Clark Kerr to Christopher Warner, June 21, 1945, F. O. 371/47862 (capital letters in original).

Meiklejohn diary, September 10–11, 1945, box 211, Harriman Papers.

John Morton Blum, ed., The Price of Vision (Boston, 1973), 447.

Dean Acheson to Mary Bundy, May 12, 1945, reel 4, Dean Acheson Papers, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Joint Planning Staff, “Operation ‘Unthinkable’,” May 22, 1945, Churchill to Ismay, June 10, 1945, CAB 120/691, National Archives, Kew.

Andrew Schlesinger and Stephen Schlesinger, eds., Journals 1952–2000 Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. (New York, 2007), 335–36.

Author notes

For helpful suggestions, I am indebted to Garry Clifford, Bob Dean, Bob Gross, Warren Kimball, Molly Hite, Emily Rosenberg, Andy Rotter, and Sherry Zane. My thanks also to Irina Bystrova for her research in Moscow.