- India

- International

Marlon Brando’s documentary is a post mortem from beyond the grave: Stevan Riley

British documentary filmmaker Stevan Riley on the enigma that was Marlon Brando and going through thousands of tapes to bring the actor to life again.

British documentary filmmaker Stevan Riley on the enigma that was Marlon Brando and going through thousands of tapes to bring the actor to life again.

British documentary filmmaker Stevan Riley on the enigma that was Marlon Brando and going through thousands of tapes to bring the actor to life again.

Blue dots and lines flicker in the centre of the screen and gradually, as though in a dance, merge to form a section of Marlon Brando’s face. Much before his death in 2004, in the 1980s, the actor had undergone a procedure to have a 3D scan of his head, rendered by Hollywood’s visual effects wizard Scott Billups. In his documentary feature, Listen To Me Marlon, based on the life of Hollywood’s “greatest actor”, Riley uses the scan to great effect — and the ghost of Brando speaks to the audience.

Riley is as chameleon-like as his latest subject. While his first documentary, Rave Against the Machine (2002) explored the underground music scene in Sarajevo during the Bosnian War, his second, Blue Blood, was about varsity boxing rivalry between Oxford and Cambridge universities. In 2010, he won a slew of awards for Fire in Babylon, about the record-breaking West Indies cricket team of the 1970s and ’80s, before making Everything Or Nothing: The Untold Story of 007, about the James Bond franchise in 2012. In Mumbai last month for a screening of his latest film at Johnnie Walker The Journey, a multi-disciplinary arts festival, Riley chats about listening to Brando’s tapes, the divide between myth and reality and why the actor’s daughter walked out of the first screening. Excerpts:

You seem to be interested in an eclectic range of subjects — from boxing to the West Indian cricket team, James Bond, and now Brando. How did this film come about?

The same production company that I have done those films with got in touch with me and asked if I would be interested in doing a film on Marlon Brando. I like taking on new topics — I didn’t know much about boxing or West Indian cricket, I don’t like Bond, so I’m usually looking for a story within these subjects that I would like to tell. You’ve got to please yourself, too, if you’re working on something for a year, two years.

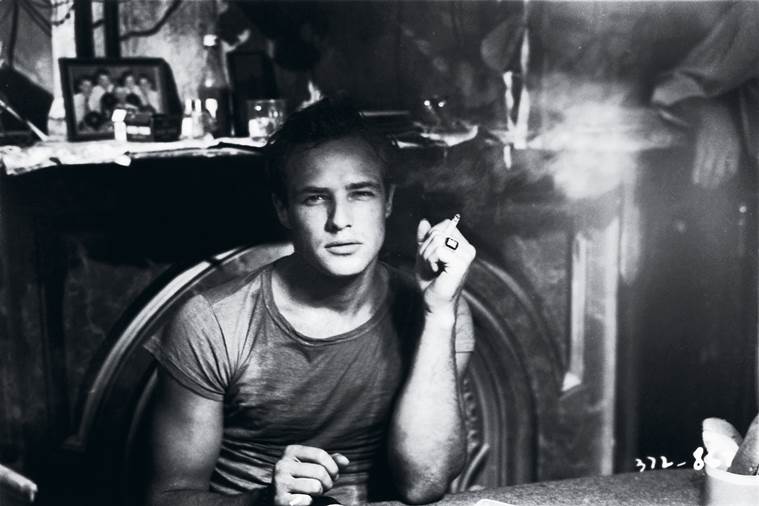

Songs his mother taught him Marlon Brando in the Broadway play, A Streetcar Named Desire; and Riley

Songs his mother taught him Marlon Brando in the Broadway play, A Streetcar Named Desire; and Riley

With Marlon, I had a blank canvas. I knew that he was psychoanalytical and in therapy for most part of his life. He recorded his conversations with himself and other people, his creative exercises, his self-hypnosis tapes, even his answering machine tapes. So I thought, what if Brando could do a psychoanalysis of himself? I read all the books about him but I started to get a little confused because of the different versions of him and I wondered, who was the real guy in between?

Brando’s estate gave you all his audio recordings of conversations with himself, over 200 hours of recordings, and many times, you were the first person to listen to them. How did you decide the direction your film was going to take?

He was an obsessive examiner of his self and human behaviour or consciousness. The archives were just being catalogued around the time the film was coming into being, 10 years after he passed away in 2004. I don’t know if those tapes will ever be released to the public, it was a big enough task to get them for the film.

Firstly, I wanted to figure out his character, who he was. He constantly asked himself, “Why is it we behave the way we do?” and I was applying that question to him. He was a very philosophical man, he was in search of meaning all his life. I’d listened to some of the tapes that had come out of the boxes and there was promise there. I thought it would clear all the confusion I was going through if Marlon was the person delivering his own story, which is what he had always wanted to do.

I took the title of the film from one of his many self-hypnosis tapes and the film was financed on the basis that the story would be in Marlon’s own words. I did interview his friends and family but it was a backup plan, only if the original tapes could not be used. His personal assistants were most interesting — these were women who worked for him, had relationships with him. If the tapes hadn’t worked out, I would have looked at the story through these women.

In the movie, one gets a sense of watching Marlon find himself in a house full of mirrors. There’s a constant collision between myth and reality. What did making the film teach you about the phenomena of celebrity and myth-making?

All his life, Marlon cherished his freedom. He was a voyeur, he liked to watch people in coffee shops and cigar shops in Manhattan, see if he could figure them out in a few seconds. The acting was always an extension of his search for truth. He was always an idealist but he got to a point in his life where he thought, “acting is a lie. Life is a lie”. He was constantly exploring myth versus truth, how quickly we lose sight of reality, how willingly we want to escape it. In his career, he liked to explore extremes, to look at good and evil and know the boundaries of experience.

But the effects of fame deprived him of that. When you tell people that Brando didn’t like being famous, they turn around and say that’s just rubbish, all actors like fame and if they don’t, they’re in the wrong profession. I don’t think that should be the case; we don’t treat artists that way, do we? Eventually, Marlon was overcome by the myth of Brando. And in the film, I look at how he went to regressive hypnotherapy to find his childlike self, the little boy (he was), and to parent himself before the wolves came in. It’s a post mortem from beyond the grave.

Was there anything you decided to leave out of the film?

Well, there was stuff where he was with women and he’d put the recorder on because he thought it would be fun; they knew he was recording them. There was nothing really off-limits with Marlon, because he went to all sorts of places, dark places too.

There was one love affair he had with an actor he met on the set of Candy (1968). When I was speaking to people, asking who was Marlon’s true love, her name, Jill Banner, kept popping up. I investigated her story a bit more: they had a tempestuous relationship but Marlon pushed her away completely. They reconciled later but she died in a car accident two weeks after that.

How has Brando’s family reacted to the film?

When I showed Rebecca, Marlon’s daughter, the film, she walked out after an hour. I was very anxious but she came back to tell me that it was overwhelming to see her father like that, he was too present for her at that moment. But she’s been very supportive of the documentary and has attended many screenings since.

Click for more updates and latest Hollywood News along with Bollywood and Entertainment updates. Also get latest news and top headlines from India and around the World at The Indian Express.

Photos

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05