Lincoln's War Powers: Part Constitution, Part Trust

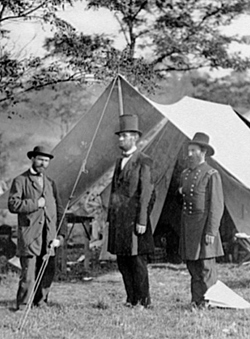

Lincoln at Antietam in the autumn of 1862, flanked by Allan Pinkerton and Maj. Gen. John Alexander McClernand. Photo by Alexander Gardner

Abraham Lincoln’s presidency was in crisis from the very start. By the time he was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, seven Southern states already had seceded.

And with the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston, S.C., on April 12, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln faced a rebellion “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.”

The Constitution lacked a definition of the war powers that could be exercised by the president, and there were few precedents upon which Lincoln could rely in responding to the war. Yet, believing that he held an awesome power as commander-in-chief and that suppressing rebellion was more an executive function than legislative, Lincoln acted in a way he saw best for the survival of the nation as a union of states. After all, his presidential oath prescribed by the Constitution required him to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” and “to preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Lincoln’s message to Congress in special session on July 4, 1861, in defense of his unilateral actions, including suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, makes this clear:

“The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed were being resisted, and failing of execution in nearly one-third of the states. … Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the government itself to go to pieces, lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the government should be overthrown, when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it?”

Lincoln also believed the president is best positioned to determine how much power he needs. Early in the war, Gen. David Hunter issued an emancipation order for Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. Lincoln revoked it, describing the decision to free slaves as power “I reserve to myself.”

It was not until Sept. 22, 1862, that Lincoln issued a preliminary emancipation proclamation under his powers as commander-in-chief “to take any measure which may subdue the enemy.”

‘GOOD MEDICINE’

Lincoln also recognized that the extraordinary powers granted the president during wartime were limited to the duration of the emergency. His reply to Erastus Corning and a group of New York war Democrats who had criticized his actions was evidence that President Lincoln was no dictator:

“I can no more be persuaded that the government can constitutionally take no strong measures in time of rebellion, because it can be shown that the same could not lawfully be taken in time of peace, than I can be persuaded that a particular drug is not good medicine for a sick man because it can be shown not to be good for a well one.

“Nor am I able to appreciate the danger apprehended by the meeting—that the American people will, by means of military arrest during the rebellion, lose the right of public discussion, the liberty of speech and the press, the law of evidence, trial by jury and habeas corpus throughout the indefinite peaceful future which I trust lies before them—any more than I am able to believe that a man could contract so strong an appetite for emetics during temporary illness as to persist in feeding upon them during the remainder of his healthful life.”

Read all the articles in our special report:

- An Inescapable Conflict

- Lincoln and Davis: A Friendship That Made History

- Secession: How the South Nearly Won

- Lincoln’s War Powers: Part Constitution, Part Trust

- The Dawn of a Republican Court: Lincoln’s Justices

- The End of War and Slavery Yields a New Racial Order

- The Conspirators: Tried by Military Commission

- Gallery: Civil War-Era Legal Figures

Although the bases for Lincoln’s actions were rooted in the Constitution, in the eyes of many his acts were extraordinary and unprecedented expansions of executive authority. Supporters as well as opponents criticized him as a “dictator.” A dictator does not go out of his way to respect legal limits as Lincoln did, including elections, despite his belief that the emergency required special measures.

How can we describe Abraham Lincoln as war president? It is beyond cavil that he saved the Union, and that there was no one else in his time who could have done so. He had a high standard of leadership as he called forth the resources of the country. He set strategy and took the necessary steps to restrain those who cooperated with disunionists. His rhetoric inspired the people—all within a constitutional framework.

Today, we face issues similar to those that confronted Lincoln. It is the perennial struggle between national security and civil liberties as the United States is the target of many who would destroy it. If those responsible for the preservation of our country are not permitted measures to save it, there will be nothing left to save. But we can only hope that our presidents will be as Abraham Lincoln: patient, pragmatic and possessing political sensitivity.

Frank J. Williams, founding chairman of the Lincoln Forum, is the retired chief justice of the Supreme Court of Rhode Island. For this article, he was assisted by Nicole Dulude, Esq.