Will British people ever think in metric?

-

Published

-

comments

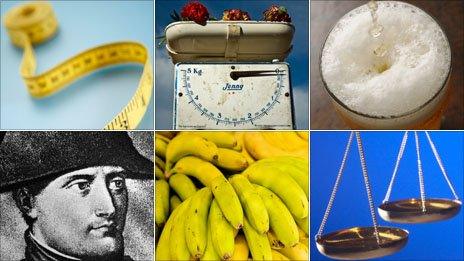

It is 200 years since Napoleon backtracked on his grand scheme to make his empire metric, but today the British remain unique in Europe by holding onto imperial weights and measures. With the UK's relationship with its neighbours under scrutiny, can it ever adopt the metric mindset?

It's an existential question that reveals much about how you make sense of the world. Is your ballpoint pen 6in long or 15cm?

Do you buy petrol by the gallon or the litre? Cheese by the ounce or the gram? And just how far is Dover from Calais - 21 miles or 34km?

Call it a proud expression of national identity or a stubborn refusal to engage with the neighbours. Either way, the persistent British preference for imperial over metric is particularly noteworthy at a time when its links with Europe are under greater scrutiny than ever.

Supporters of traditional weights and measures may have rejoiced in 2007 when the European Commission announced it was dropping its attempts to bring the UK into line with the rest of the EU.

But a looming anniversary is a reminder to decimal sceptics and enthusiasts alike that successful resistance to metrication is not always permanent.

In February 1812, some 17 years after France first went metric, Napoleon I introduced a system for small businesses called mesures usuelles - French for customary measurements. These were based on the old, pre-revolutionary system, in response to the unpopularity of the new decimal codes.

Only after Napoleon's departure did France go fully metric in 1840, using the law to enforce metrication.

But if the French eventually learned to think in units of 10, the UK, so far, has not. All the evidence suggests that, despite more than decade-and-a-half of goods being labelled in both metric and imperial, the British remain defiantly out of step with their counterparts across the channel.

In May 2011, a survey by supermarket chain Asda suggested 70% of customers found metric labelling confusing and wanted products labelled in imperial instead. In response, the company reverted to selling strawberries by the pound for the first time in over a decade.

According to social historian Joe Moran, author of Queuing For Beginners, the notion that imperial measures embody tradition and reassurance accounts for much of their appeal to the British.

"It may also have something to do with the poetic, concrete names used in the old imperial system, particularly for coins - tanner, half a crown, guinea, etc, that just seem more familiar, friendly and native than metrics."

Nonetheless, the legal requirement to display measurements for most products in both systems means many Britons have become adept at making the mental switch from ounces to grams and back again.

Nowhere is this duality more apparent than in relation to alcohol. Imperial measurements for spirits were phased out in 1988. Yet it remains illegal to sell beer and cider in any other units than pints.

It is a discrepancy that is reportedly mirrored in the illegal drugs market, with cannabis typically sold in ounces while cocaine is packaged in grams.

However, support for traditional measurements has gone beyond shoppers merely expressing a consumer preference.

In 2001, grocer Steve Thoburn became a cause celebre - if French terms are not inappropriate in this context - after being convicted for using scales showing only imperial weights. The Metric Martyr group's appeals against conviction were rejected all the way up to the House of Lords and, in February 2004, by the European Court of Human Rights.

Given the widespread association in the UK between the metric system and the European Union, it's tempting to view the battle simply as an expression of hostility towards political integration.

For one of the Metric Martyrs, Neil Herron, however, it was primarily concerned with how we understand the world around us.

"It's about the language and vernacular with which we relate to each other," he says. "Even with kids who have been educated in metric for the past 30 years, watching a football match talk about a penalty kick being 12 yards or the striker being six foot tall.

"It goes to the core of who we are. If we are going to change we will do it organically, with the consent of the people. We won't have it imposed."

Despite its popular identification with European bureaucracy, British attempts to scrap imperial measurements stretch back long before the UK came under the jurisdiction of Brussels.

In 1863 the House of Commons voted to mandate the metric system throughout the Empire, and in 1897 a parliamentary select committee recommended compulsory metrication within two years. In 1965 the Confederation of British Industry threw its weight behind the cause and the government set up the UK metrication board in 1969, four years before the UK joined the European Common Market.

Joining the community meant signing up to directives on standardised measurements, although the deadline for implementation was repeatedly pushed back. Since 1995, goods sold in Europe have had to be weighed or measured in metric, but the UK was temporarily allowed to continue using the imperial system.

This opt-out was due to expire in 2009, with only pints of beer, milk and cider and miles and supposed to survive beyond the cut-off. But ahead of the deadline, the European Commission admitted that persuading the British to accept grams over ounces was a lost cause, and shops could continue to label products in both systems.

To supporters of metric measures, it is a source of frustration that what they regard as a more logical mechanism has never achieved predominance.

Robin Paice of the UK Metric Association insists there is nothing intrinsically British about miles and pints and, for that matter, nothing inescapably foreign about kilometres and litres.

"I don't believe things are hard-wired into the national mentality," he says.

"The government has done very little to explain why it would be to the benefit of the UK to use the world's system. If people are asked to change the habits of a lifetime without explanation they are naturally quite reluctant. It's very much a failure of leadership."

The UK may have the failure of Napoleon's armies to cross the channel to thank or blame for the resistance of imperial. But it is not the only country to fail to enthusiastically embrace metrication.

Japan's traditional shakkanho system was supposed to have been replaced by metric in 1924, but remained popular. It was forbidden in 1966 but is still used in agriculture.

And of course the US continues to weigh and measure in customary units, a system derived from imperial. According to Moran, the similarities between the two codes has served to reinforce UK Atlanticism.

"Our residual attachment to imperial weights and measures is really to do with a resilient fact about our geo-political position: we are an island with one eye on America and an ambivalent attitude to the continent," he says.

"In Britain the metric system has been associated with mainland Europe and also, since Napoleon, with European imperialism. The Americans used a set of weights and measures that was a variant on the imperial - and Americans coming over here in the war probably strengthened the sense that we had this in common."

Switching between imperial and metric, the UK's approach to the issue may mirror the debate about its place in the world. But whichever way you measure it, the Channel isn't getting any larger or smaller.