Protests engulf west Iraq as Anbar rises against Maliki

-

Published

The tribes of the mainly Sunni western Iraqi province of Anbar are furious at Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, and have picked an unusual spot to showcase their anger.

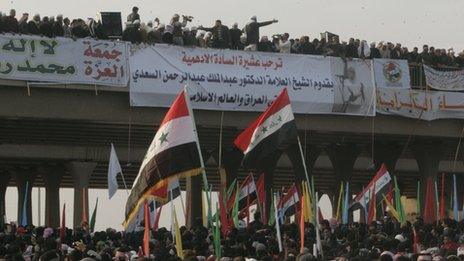

Along a stretch of the Iraqi international highway leading to Syria and Jordan, a tent city has sprung up, each tent bearing the banners of tribes and delegations from different cities.

The tent city, near the provincial capital of Ramadi, is the focal point of a wider protest movement which started after the army raided the office of a senior Sunni politician from the province, and arrested some of his bodyguards.

This comes more than a year after former Vice President Tariq al-Hashemi, another prominent Sunni leader, was charged with involvement in terrorism. He has since been handed three death sentences in absentia.

For the protesters, it all points to a campaign of revenge against the Sunnis of Iraq by a prime minister who they say is loyal to mainly Shia Iran.

They say the prime minister has unleashed a pliable judiciary on his political opponents in order to tame the opposition.

"We warn the sectarian government against dragging the country into sectarian war," says the banner on the Fallujah Youth Council tent.

"Al-Boudiab tribe demands that the Maliki government release the Sunni men and women of Iraq from the government's Persian jails," reads the banner on another.

The most emotive issue is that of women prisoners the protesters say have been arrested instead of husbands or sons who are wanted on charges of terrorism.

"It's now a question of honour," said Sheikh Ali Hatem Suleiman, one of the most powerful tribal sheikhs in Anbar, to loud applause from the protesters.

"Not politics, not the constitution, not even the United Nations can resolve it. We want the women released here in the square."

Wildcard

Sectarian division is written all over the dispute. Mr Maliki is supported by many Shia who believe they are the target of the regular bombings that strike Iraq.

He is anchored in power by a dominant Shia coalition, which despite its diversity, has remained mostly impenetrable to the Sunni opposition.

But there are exceptions. Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, who heads a powerful bloc in parliament, once split from the coalition and joined an unsuccessful campaign to unseat Mr Maliki.

Today, as Anbar simmers with rage, Sadr is playing a wildcard again.

He has lent his cautious support to the movement, sending delegations of his supporters from southern Iraq to the tent city, and opening a crack in the sectarian narrative.

After an initial outburst of sectarian rhetoric, everyone at the camp was keen to stress that this is "about Maliki and Iran, not the Shia".

"We've cleansed our hearts of this Shia-Sunni thing," said one activist. "They want to turn it into a sectarian struggle so they can keep the Shia on their side."

Among the protesters, there is an attempt to defuse the sectarian dynamic before it sets in. But suspicion is deeply rooted.

As they shared stories about intermarriages, tribal ties, and ordinary people getting along, one activist broke ranks and lashed out at the Sadrists.

"They're also loyal to Iran," he said. "Do you really want to allow Moqtada to use our movement in order to gain ground in his struggle with Maliki?"

'Iraq is not Syria'

The protest movement in Anbar poses a significant challenge to the government's authority, and Mr Maliki has responded with mixed signals.

He has acknowledged the possibility of abuse inside prisons, and promised investigations into the issue of women prisoners. But he also lashed out against "blabber" that would lead to civil war and the partitioning of Iraq.

"There are states sponsoring an attempt at creating a new Syrian situation within Iraq," he told the Iraqi television station Sumariya.

"But they and those who support them have miscalculated. Iraq is not Syria."

The regional dimension of the struggle is not lost on the protesters, although they would disagree with Mr Maliki's interpretation.

The flag of the Syrian revolution figures prominently among the assortment of banners in the tent city, along with the former flag of Iraq under Saddam Hussein's Baath party.

"No-one took our opinion when they changed the flag," Sheikh Ali Hatem told me.

Radical mood

In the "media tent", young men with laptops organise events, write statements, and update the movement's Facebook page.

"We shall continue the revolution which began in Syria," one of them told me.

He outlined the movement's demands, including the release of prisoners, the cancellation of anti-terrorism legislation - which he said targets Sunnis - and the revoking of the Justice and Accountability act, an extension of the de-Baathification law which was brought in after the fall of Saddam Hussein to remove the party's influence from politics.

What if the government concedes to the demands, I asked?

"Then we want an end to Sunni marginalisation, balance within state institutions, and jobs for the unemployed."

What then?

"Then we have a different set of demands which we will announce later," he said with a smile.

As Sunni clerics and delegates shuttle back and forth between Anbar and Baghdad, a radical mood is taking hold in Ramadi.

The deputy Prime Minister Saleh al-Mutlak, a Sunni who has had many quarrels with Mr Maliki, was chased off stage after protesters hurled shoes and water bottles at him.

Anti-government feeling here is extending to senior Sunni politicians who are part of the political process in Baghdad.

"Shame and dishonour to those who betrayed the cause," read the banner outside the Al-Boujaber tribe's tent.

Sheikh Ali Hatem took to the stage several times to assure the crowd that there would be no deals with Baghdad behind their backs.

"Let anyone who wants to negotiate come and negotiate here with you," he announced.

"This is the revolution of the youth, not of the tribes," he later told me. "The sheikhs can no longer control it."