Story highlights

Clinton delivered a speech attacking the movement

The alt-right has been accused of racism, misogyny and anti-Semitism

Previously confined to darker corners of the internet, the alt-right is moving into the spotlight.

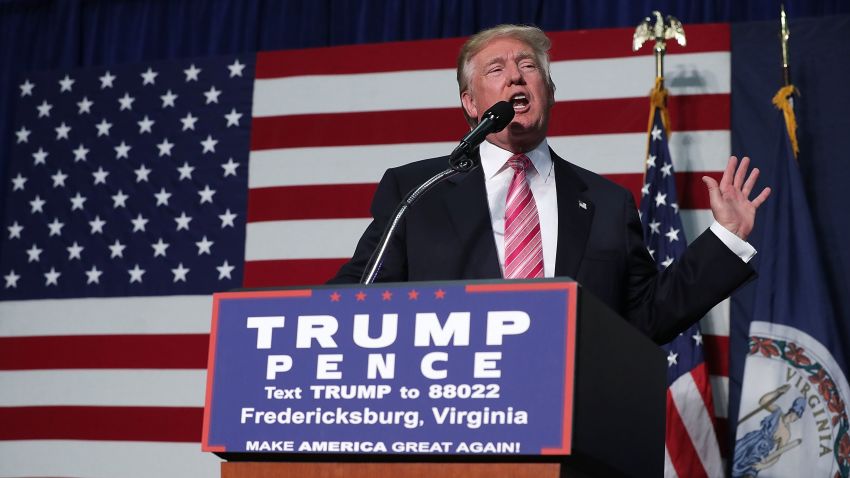

Donald Trump linked himself to the movement last week by hiring Breitbart’s Steve Bannon as his campaign CEO, elevating one of the leading purveyors of an ideology steeped in white nationalism, misogyny and anti-Semitism to his inner circle.

Though the alt-right movement is not a Breitbart creation, the site has served as a reliable outlet for its more polished and popular advocates. In July, Bannon bragged to Mother Jones that his site had become “the platform for the alt-right.”

Hillary Clinton on Thursday afternoon delivered a speech aimed at connecting her opponent to the movement’s ugliest elements.

“He is taking a hate movement mainstream, peddling bigotry and prejudice and paranoia,” Clinton told CNN’s Anderson Cooper on Wednesday night.

In Nevada, Clinton took on the alt-right by name, singling it out as an “emerging racist ideology.”

“The de facto merger between Breitbart and the Trump campaign represents a landmark achievement for this group, a fringe element that has effectively taken over the Republican party,” she said, tying the movement to “the rising tide of hardline, right-wing nationalism around the world.”

Trump, during remarks earlier on Thursday in Manchester, New Hampshire, lashed out at Clinton.

“The news reports are that Hillary Clinton is going to try and accuse this campaign and all of you and the millions of decent Americans – … it’s a movement like we’ve never seen before – and they’ll accuse decent Americans who support this campaign, your campaign, of being racists, which we’re not,” Trump said.

Here’s a look at the alt-right movement, what it stands for, and why it’s stirring up so much controversy.

What is the alt right?

First, what it is not. The alt-right is not a traditional, hierarchical political movement. It is not rooted in a single organization, founding alliance or ideology.

But at its grassroots, the alt-right is animated by many of the same class, gender and racial anxieties that have helped fuel right-wing nationalist movements across Europe and, as Trump’s critics argue, the Republican nominee himself.

In late March, Breitbart published something close to a manifesto. Titled “An Establishment Conservative’s Guide To The Alt-Right,” writers Allum Bokhari and Milo Yiannopoulos presented the movement as an intellectually vibrant – in contrast with “1980s skinheads” – band of merry right-wing pranksters “eager to commit secular heresies” while striking out at political elites, regardless of their party affiliation.

They exist almost exclusively online, talking to each other on alt-right blogs and select reddit or 4chan forums. To the extent a “normie” – alt-right and web slang for a normal person – is likely to encounter them, Twitter has emerged as the preferred avenue for the harassment and trolling of assorted rivals, enemies and other targeted groups, often women and Jews.

And that is very much central to understanding the alt-right. As Yiannopoulos wrote, many of its self-identified members are drawn less by a desire to enter the current political debate than an instinct to undermine it while delighting in a sense of “fun, transgression, and a challenge to social norms they just don’t understand.”

But the reality is less rosy. Yiannopoulos was banned from Twitter for serial aggressions, including his part in the recent campaign targeting comedian Leslie Jones.

What do they believe in?

The alt-right is at its core a rejection of American multiculturalism and the conservative establishment, its leaders’ writings show.

The National Policy Institute’s Richard Spencer, an alt-right founder, writes on his RadixJournal.com that the site is “dedicated to the heritage, identity, and future of European people in the United States, and around the world.”

Though it often cloaks itself in an impenetrable mix of pseudo-intellectualism and internet memes, the movement’s underlying themes are pretty simple.

They oppose any level of immigration that would threaten white demographic dominance and advocate for a muscular white nationalism. The alt-right is also particularly concerned with “political correctness” – which its adherents despise – viewing any attempt to reconcile across cultures and races as evidence of weakness in those who seek it.

Some of the alt-right’s harshest rhetoric has been directed at establishment conservatives, often derided as “cuckservatives”– a joining of the words “cuckold” and “conservative” – whose moderate political positions on immigration and race are met with misogynist slurs and mocking.

A glossary of alt-right terminology and coded language on “The Right Stuff” blog defines the shorthand “cuck” as a “an epithet for a weak man” – in their worldview, one of the most damning insults.

Why are we talking about the alt-right now?

That Clinton is addressing the movement at all is being taken by leaders and followers as a mark of its success.

More broadly, their terminology and signage have begun to trickle into more mainstream venues. When New York Times editor Jonathan Weisman announced in June that he planned to quit Twitter because of harassment by anti-Semitic trolls, the abuse included alt-right imagery and signals.

In particular, the use of “echoes” or a parentheses surrounding his name – “Hello ((Weisman)),” @CyberTrump tweeted at him after Weisman shared an opinion piece critical of Trump – has direct ties to “The Right Stuff” and its podcast, “The Daily Shoah.”

To moderate conservatives, the alt-right represents the latest front in a long war for control of the broader movement. Trump’s ascendance has renewed fears that the right as a whole could be consumed or at least lose its mainstream appeal if the Breitbart voice gains too strong a foothold in GOP party politics. Bannon’s arrival in particular heralded a setback in a decades-long struggle.

As Matthew Continetti wrote in Commentary before the hire, the man regarded as the father of modern conservatism, the late William F. Buckley Jr., plotted its ascendance by shutting out extremists on the right.

“By exiling anti-Semites, Birchers, and anti-American reactionaries from its pages, the magazine and its editor determined which conservative arguments were legitimate and which were not,” Continetti argued. “By denying a platform to quacks and haters, they broadened their potential audience.”

The alt-right is regarded as a threat to the sustainability of that mainstream conservatism as a national political force.

Why does the alt-right love Trump?

For the alt-right, the Trump campaign has been a more natural landing place than the broader Republican party. Trump’s aggressive anti-immigrant policies, proposed Muslim ban and authoritarian rhetoric, along with the rage and frustration it stokes on the left, mirror many of the group’s beliefs.

Like the candidate, when Breitbart’s Yiannopoulos is confronted over some provocation or degrading comment he will most often pivot and try to pin the blowback on a “politically correct” culture bent on silencing its opponents.

“Twitter is holding me responsible for the actions of fans and trolls using the special pretzel logic of the left,” he said after being suspended permanently from the service last month for repeatedly inciting abuse.

Trump has not veered as far afield of the mainstream, but the sense of an American identity having come under assault by a coalition of the US establishment and “globalist” forces is a recurring theme in the alt-right and in his campaign.

Clinton’s speech, as “Right Stuff” blogger “Tharru” speculated on Wednesday, could be a defining moment for the campaign.

“For him, (being asked to disavow the ideology) would likely be the defining moment for his campaign, our future prospects, and the possible avenues Whites in America will tread. He either has to man up and take on the anti-White press and their financiers explicitly in the name of the Alt-Right or he leaves us high and dry,” Tharru wrote.

“There was a market for this. It was us. He filled it.”

Minutes after Clinton’s speech wrapped on Thursday, the white nationalist magazine “American Renaissance” put out a statement saying that while “the Alt Right generally supports Donald Trump because of his positions on immigration,” he would not qualify as a member.

“Claims that Donald Trump, his campaign, or his mainstream media allies such as Breitbart.com are part of the Alt Right are wrong,” American Renaissance said. “Mr. Trump and Breitbart stand for a civic nationalism and believe in secure borders. They take no position on white identity or race and IQ, which are central positions of the Alt Right.”

Why does the alt-right hate Clinton?

As both a political actor and individual – as a woman – Clinton neatly encompasses nearly all of the alt-right’s most prevalent hobgoblins.

Her longstanding and comfortable relationship with the big banks and global finance community fits their caricature of an elite that, as one Twitter user put it, would have Clinton be “a friend to every country but her own.”

But the more visceral alt-right anger tends to revolve around her campaign’s embrace of multiculturalism – across race, gender and religion – and the fact that Clinton, now aspiring to the most powerful elected office, is a woman.

The language of the movement is soaked through with the tone and terminology employed by “male rights” activism. The imagery it uses to depict Clinton – either in unflattering photos or body-mocking illustrations – is divorced from any policy dispute or debate.

For the alt-right, the idea of socially progressive, female commander-in-chief is a “heresy” they cannot bear.