The Georgia Secession Convention of 1861 represents the pinnacle of the state’s political sovereignty. With periodic interruptions, the convention met in Milledgeville from January 16 to March 23, 1861, and not only voted to secede the state from the Union but also created Georgia’s first new constitution since 1798. Politically the convention was a watershed event that hastened the Civil War (1861-65) and dramatically changed the course of Georgia history.

The idea of state secession emerged in the late eighteenth century as tensions developed over the interpretations of state versus federal powers as enumerated by the U.S. Constitution. Earlier conventions, including various nullification conventions in the 1830s and the southern conventions surrounding the crisis over slavery in 1850, considered the act of leaving the Union. Still, none adopted an official proclamation until the South Carolina Secession Convention in December 1860.

The escalating sectional crises over slavery in the 1850s contributed to the volatile tensions that arose during the 1860 presidential campaign. Abraham Lincoln’s election in November of that year caused a fiery backlash in the southern states, which feared the abolitionist policies of the Republican Party. The result was a series of state conventions across the South, beginning with South Carolina’s in December. The fifth such convention occurred in Georgia, a pivotal state in the debate due to its geographic importance to the region, the stature of its congressional delegation as leading voices for southern grievances, and its economic value as a major cotton producer.

On January 2, 1861, a miserably rainy day, Georgia voters went to the polls and selected delegates to a convention that would decide the state’s response to Lincoln’s election. In many counties the candidates divided along two divergent views. Immediate secessionists advocated leaving the Union without further consideration. Cooperationists, however, tended to be more conciliatory. Their opinions ranged from maintaining a devout Unionism, to desiring a scheme in which the South acted in unison, to advocating a delay of the act of secession. Low voter turnout due to the poor weather may have affected the election’s outcome, but the immediate secessionists finished with a slight majority of delegates. Political speeches, newspapers, and the contentiousness of state leaders reveal the deep divisions over the issue of secession at that time.

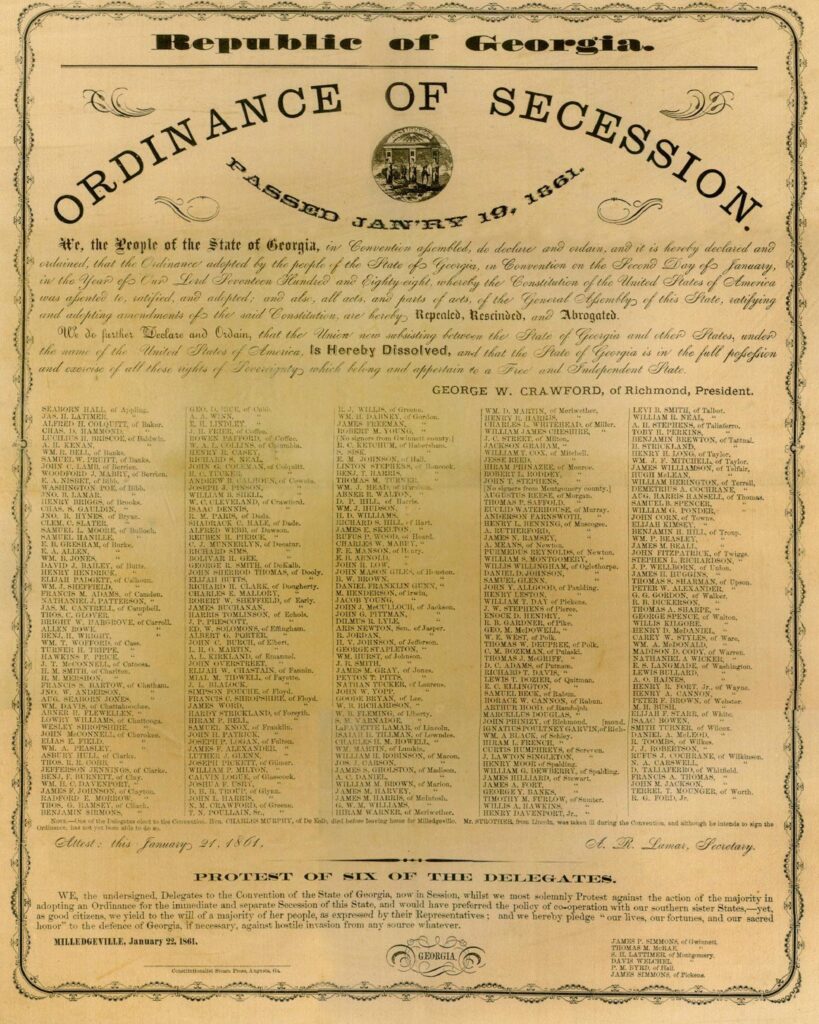

Once the delegates convened in Milledgeville on January 16, they wasted little time in testing the mood of the convention. After the rules and procedures for the meeting were established on the first day, countering proposals alternated between such immediate secessionists as Eugenius A. Nisbet and cooperationists like Herschel Johnson. Early votes indicated that there might be a close contest: one resolution demonstrated that the split between the immediate secessionists and the cooperationists was as close as 166 to 130 respectively. In the end, however, the final vote on January 19 revealed a major shift in the convention for immediate secession, when the cooperationists failed by a tally of 208 to 89. With this vote at two o’clock in the afternoon, the convention president, George W. Crawford, proclaimed Georgia officially seceded from the Union. Celebrations across the state drowned any lingering dissent from cooperationists or Union loyalists.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The delegates reconvened on January 21 to begin a new phase of the convention—that of writing a new constitution for the state. In many aspects the Georgia Constitution of 1861 resembled that of the Constitution of 1798. There were, nevertheless, some notable differences. The 1861 document made specific provisions for the protection of slavery in the state. The new constitution also took away the amending power of the assembly and gave it solely to a constitutional convention chosen by the people of Georgia specifically for that purpose.

The convention adjourned temporarily to allow a committee time to write the new constitution and to await the outcome of the Confederate Convention at Montgomery, Alabama, in February 1861. Reconvened in March, the Georgia Secession Convention, now a constitutional convention, ratified the new Confederate Constitution and voted to submit the new Georgia constitution to the people by ballot in July. The delegates adjourned for the last time on March 23, 1861. Nearly three weeks later, on April 12, Confederate batteries fired on federal troops at Fort Sumter, in South Carolina, and thus began hostilities in the Civil War.