George H.W. Bush was the last of his kind.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jon Meacham, who wrote a biography of the 41st president, calls him "the last gentleman." He was the last American president to start a war, fight it and win it. And, most important in the sweep of American political history, he was the last president who embraced and embodied a moderate brand of Republicanism that was in decline before he took office and has all but disappeared since.

Bush straddled the divide between the movement conservatives of President Ronald Reagan and the old liberal, northeastern wing of the GOP led by figures such as former Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, landing a spot on Reagan's ticket in 1980 after a bitter primary fight. That launched him on the path to the presidency, which he would win in 1988 despite the misgivings of some grassroots conservatives.

From the Oval Office, Bush presided over the fall of the Berlin Wall, the swift defeat of Iraqi forces that had invaded Kuwait, the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the extension of the Civil Rights Act, the expansion of environmental regulations and a 1990 budget deal that both set the country on a path to fiscal stability while it permanently turned his right flank against him because the law included tax increases.

"He liked to legislate," said Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, who served as director of legislative affairs in the Bush White House.

But Bush's internationalist approach to foreign policy — a function in part of his experience as a Navy bomber pilot in World War II, a U.S. representative to the United Nations, an envoy to China and a director of the Central Intelligence Agency — was his greatest legacy, according to presidential historians.

"He should be given credit for how he performed in the presidency, that leadership role of internationalism, multilateralism, free trade, international law, international associations," said Barbara A. Perry, presidential studies director at the University of Virginia's Miller Center. "That was such a successful model for fighting the Cold War, ending the Cold War and going into the 1990s and the 2000s."

New England roots, Texas growth

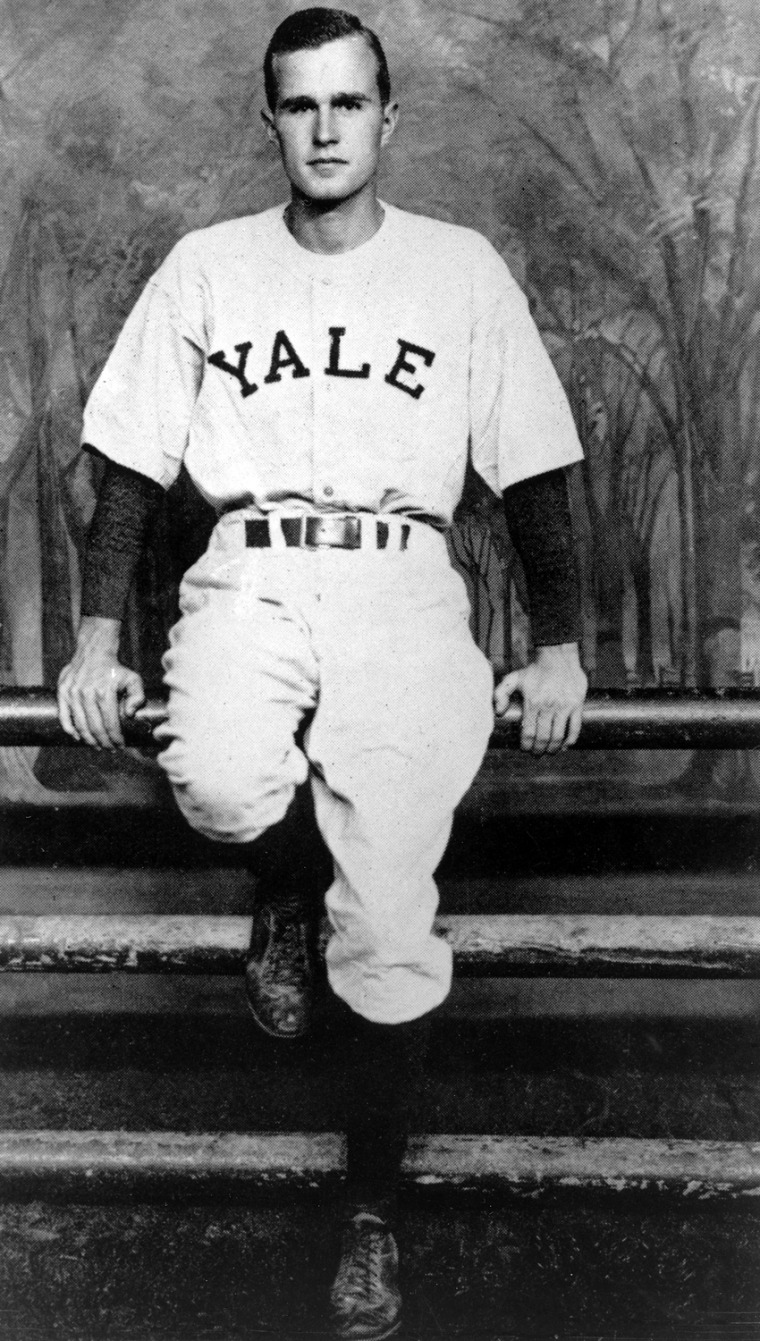

Rising in an era of self-made Republicans like Reagan and President Richard Nixon, Bush's politics were the product of two very different environments: the New England of his youth, where he grew up the son of investment banker and future Sen. Prescott Bush of Connecticut and played first base for the Yale baseball team, and Texas, where he took his growing family in search of oil riches.

He won election to the House in 1966, and, in a show of the favor he would continue to cultivate in Republican circles, wangled a rare freshman assignment to the tax-writing House Ways and Means Committee. Bush's landmark legislation was the creation of Title X, which provides federal funding for family planning programs, a push that earned him the derisive nickname "rubbers" from his colleagues and marked him as a social moderate at a time when the party was in the early stages of a hard right turn on cultural issues.

After losing a 1970 Senate race against Lloyd Bentsen — who portrayed him as too liberal and a Nixon stooge — Bush's loyalty to the party was rewarded when Nixon appointed him to the U.N. post. He would leave that job for the chairmanship of the Republican National Committee, where he was charged with leading the party during, and in the immediate aftermath of, the Watergate scandal. He leaned on Nixon to resign for what he said was the good of both the party and the country.

And then Bush went to China to represent the U.S. as President Gerald Ford's top diplomat there. His title, chief of the U.S. liaison office to the People's Republic of China — rather than ambassador — suggests just how new and delicate the relationship between the two powers was at the time.

Reagan's No. 2

Surely, no one in either party had a resume to match Bush's when he won Iowa, the first contest in the 1980 GOP primaries. But eventually he succumbed to Reagan, who had nearly thwarted Ford's renomination bid in 1976. Reagan didn't want Bush — who had called his supply-side theories "voodoo economics" — but he needed balance on his ticket to unify his conservative populist wing of the party with the party establishment.

Reagan first homed in on Ford as his running mate, but decided he couldn't manage the presidency with an ex-president who demanded near-parity. Ultimately, Reagan turned to Bush as a backup choice for the second slot on the ticket.

Bush was "a little bit of a strange bedfellow in the Reagan administration" because he didn't fit in with the hard-edged conservatism of the Reagan revolutionaries, Perry said. Like many vice presidents, he was relegated to the role of representing the president at official functions, including funerals for important figures.

"They die, we fly," Bush and his aides joked about his job.

But Bush also demonstrated a knack for making a political moment. In 1984, speaking about his debate the previous night with Geraldine Ferraro, the first woman nominated for vice president by a major political party, Bush said "we tried to kick a little ass."

While the left was outraged at what was perceived as a sexist remark, Bush was also signaling that he was the tougher candidate for the job he held.

'Selfless patriotism'

Bush easily defeated Sen. Bob Dole and evangelical leader Pat Robertson for the GOP nomination in 1988, but a tepid endorsement from Reagan underscored the discomfort of movement conservatives, who felt that he would swing the political pendulum away from them and back toward moderates.

He ran a sharp-elbowed general election campaign against Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis, the Massachusetts governor, that seized on a state prison furlough program and an inmate named "Willie" Horton. Horton, who is black, raped a white woman while out on furlough, and became a theme of Bush's speeches and the subject of an ad run on behalf of Bush that was criticized for fear-mongering and race-baiting.

Bush would go on to win the election with a whopping 426 electoral votes, nearly four times Dukakis' 111.

Just two years later, he would give conservatives reason to believe that their worst fears about his political instincts had come true.

After a briefing from Treasury Secretary Nicholas F. Brady about mounting budget deficits and their potential effect on the economy, Bush determined that the country's fiscal books had to be brought into better order.

"The president was convinced that if something wasn’t done, it would come back to hurt middle class families and the economy," said Portman, who was in the room for the session.

For months, Bush negotiated with congressional leaders from both parties and eventually decided to renege on his campaign pledge of "no new taxes" in the interest of cutting a deal with Democrats that also curtailed spending. Many analysts say that was the beginning of the end of his re-election effort, as conservatives abandoned him in a three-way 1992 race against Democrat Bill Clinton and Reform Party candidate Ross Perot.

Anita McBride, executive-in-residence at American University's Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies and an aide to Reagan and both presidents Bush, said George H.W. Bush exhibited a "selfless patriotism" in both international and domestic politics — as evidenced by his decision to break such a major campaign promise.

"He had the courage to do something he knew would lose him an election, the way Lyndon Johnson did with the Civil Rights Act," McBride said. "This had to be done for the country, when faced with all the realities of where the economy was and was headed. ... So, he didn't kick the can down the road."

Despite his break with his party's base, Bush's defeat was particularly stunning because his approval rating had risen to nearly 90 percent at the end of the Gulf War in early 1991.