Homophobia in Black Communities Means More Young Men Get AIDS

Social stigmas have paralyzed prevention efforts, activists and scientists say.

The AIDS epidemic is a solvable problem. Ending AIDS is not just an aspiration. But despite recent advancements in diagnosis and treatment, explained Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease at a recent Atlantic forum, the rate of new infections has stopped decreasing, remaining at a plateau over the last decade.

Why? At least part of the cause is the stigma against homosexuality in the black community, Fauci and others agreed.

“We can’t forget that in this country, the risk [of HIV infection] for a young gay man, particularly a young African-American man—the risk is really huge,” Fauci said. “But there’s still discrimination and stigma.”

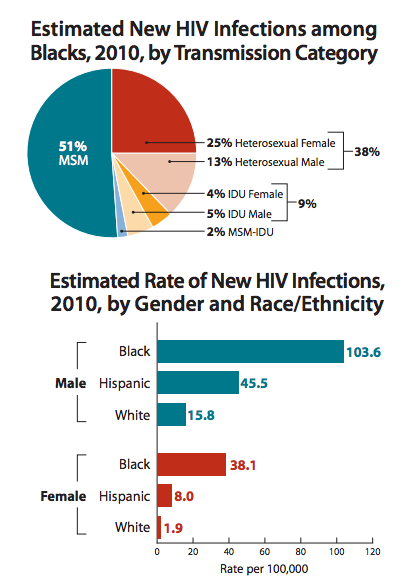

Fauci described how this problem has taken shape in Washington, D.C., where about half of the population is black. In predominantly white areas, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS is very low, he said, but in predominantly black areas, “the rate is seven or eight percent. The disparity is not only of African Americans who are disenfranchised from health care, but also the difficulty of social acceptance in the African American community of a gay man of color.”

men who have sex with other men, or "MSM." (CDC)

This may have contributed to a shocking statistic: As of 2013, black gay and bisexual men aged 13 to 24 accounted for more new infections than any other group in the United States. Phil Wilson, the president and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute, cited an estimate that half of young, black, gay men are infected.

Yes, it’s as shocking as it sounds: Half of gay black men under the age of 24 may be infected with HIV. “We have a serious problem in this country,” Fauci said.

Pinpointing where exactly social stigma comes from and how it manifests is a big challenge, though. When asked whether this is largely the fault of religious communities, Wilson was careful.

“It’s a moral issue,” he said. Wilson pointed to a speech on homosexuality made by the prominent African-American pastor T.D. Jakes. “He said, ‘We can’t save their souls if we can’t save their lives.’ This is about meeting people where they are. The goal is to expand the prevention toolbox so that everyone can find something they can use.”

Others pointed to the growing stigma against the disease within the gay community itself. “In the eighties, 50 percent of [gay men] were HIV-positive,” said Peter Staley, an activist who was recently featured in the documentary How to Survive a Plague. “We felt we were all in it together—we fought it together.” Now, that openness to admitting to having the disease has changed among gay men. “There’s a sense of stigma—they know if they come out, they’ll be treated terribly by their peers.”

And that means more infections happen. “It’s a vicious loop, because you can take a pill and stay healthy,” Staley said. “Instead, people stay closeted.”

But prevention isn’t only an issue in the gay community: Women, and particularly black women, struggle with the continued prevalence of the disease. HIV is the leading cause of death among black women aged 25 to 34. And according to the CDC, the incidence of HIV/AIDS among black women is 20 times higher than among white women.

Many straight women get exposed to HIV during unprotected sex, but as Wafaa El-Sadr, the director of ICAP, a global health organization at Columbia University, pointed out, it might not be their fault. “The male condom is important—the data is definitive. But in many situations, [condom use] is not under the control of the woman. We need to find prevention methods that women can use to protect themselves.”

Finding protection can also be a problem for sexually active kids and teens. “Condoms take money, but kids don’t have money,” said Deborah Persaud, a professor at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. “Parents have money, but they often don’t know their kids are having sex.” Around 40 percent of sexually active kids and teens don’t use protection, she said.

Despite the apparent urgency of this issue, especially in the black community, funding for AIDS prevention has stagnated in the last half decade. “We’re dealing with a level of apathy that we have not witnessed since the earliest years of the crisis,” Staley said. “People think it’s over.”

For researchers and activists, this combination of widespread apathy and social stigmas is particularly frustrating, especially because scientists have finally figured out effective methods for managing and preventing the spread of the disease. And according to Jeffrey Sachs, a Columbia University professor and special advisor to the UN on issues like AIDS prevention, it’s not a financial issue, either. The funding needed to stop the spread of AIDS looks “chump change” in the context of the multi-trillion dollar global economy, he said.

“I’m the only living macroeconomist still talking about billions,” Sachs said. “All my friends think I’m a joke, because they’re all talking about trillions. Five billion dollars from the world: That’s three paychecks to the top three hedge fund owners.

“This is chump change, and yet this is our hard part. We do not have a financial crisis. We do not have an economic crisis. We have a moral crisis.”