The 1964 Election

“In the election this fall ... we stand for the election of President Lyndon B. Johnson.”

“In a society like ours, where every man may transmute his private thought into history and destiny by dropping it into the ballot-box, a peculiar responsibility rests upon the individual. Nothing can absolve us from doing our best to look at all public questions as citizens, and therefore in some sort as administrators and rulers. For, though during its term of office the government be practically as independent of the popular will as that of Russia, yet every fourth year the people are called upon to pronounce upon the conduct of their affairs. Theoretically, at least, to give democracy any standing-ground for an argument with despotism or oligarchy, a majority of the men composing it should be statesmen and thinkers.”

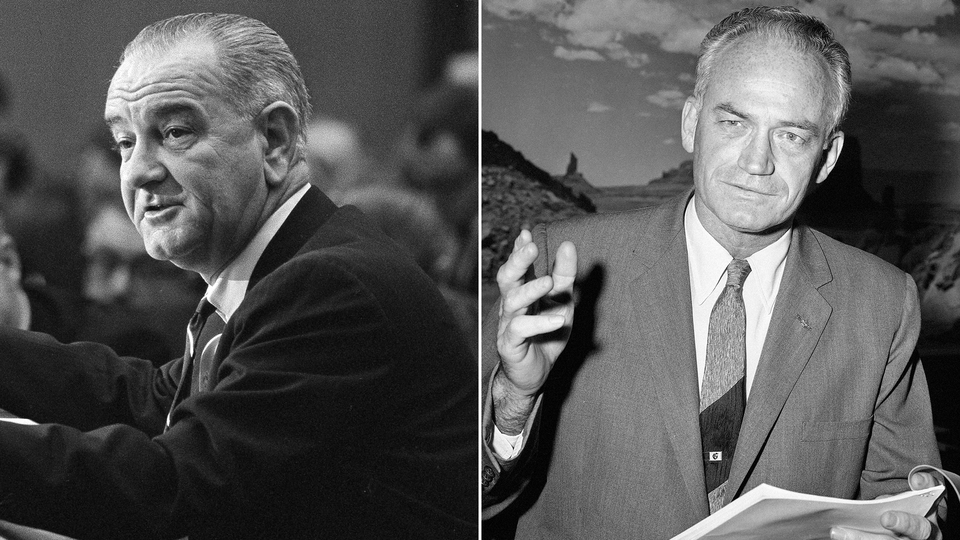

In the election this fall, which will go far to determine the conduct of the United States in the next twenty-five years, we stand for the election of President Lyndon B. Johnson. We admire the President for the continuity with which he has maintained our foreign policy, a policy which became a worldwide responsibility at the time of the Marshall Plan. We respect the quiet confidence which he has engendered among American businessmen and in the unions. We believe that as the first Southerner to occupy the White House since the Civil War, the President will bring to the vexed problem of civil rights a power of conciliation which will prevent us from stumbling down the road taken by South Africa. The firmness and the common sense with which he pressed for the passage of the tax cut and the bill on civil rights recall a remark which the late President Kennedy made to a trusted reporter when he was stumping California in the primary. “Of us all,” said JFK, “Lyndon Johnson is the best qualified for the office.”

The methods and strategy by which a politician rises to power are an index of his character. In his drive for the nomination, and ever since, Senator Goldwater has accepted the proposition that a ruthless minority taking over first the Republican Party and then the nation shall break with the past as it chooses. His proposal to let field commanders have their choice of the smaller nuclear weapons would rupture a fundamental belief that has existed from Abraham Lincoln to today: the belief that in times of crisis the civilian authority must have control over the military. His preference to let states like Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia enforce civil rights within their own borders has attracted the allegiance of Governor George Wallace, the Ku Klux Klan, and the John Birchers. His threat to walk out of the United Nations if he does not approve of its action is a repudiation of what the best brains, Republican and Democrat, have helped to contribute to that peace-keeping institution. Quick-flash utterances such as these may appeal to malcontents, but not to “statesmen and thinkers.”

A President is trusted to make decisions, the most momentous decisions in our lives. In making up his mind he must reckon with those who disagree with him. We think it unfortunate that Barry Goldwater takes criticism as a personal affront; we think it poisonous when his anger betrays him into denouncing what he calls the “radical” press by bracketing the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Izvestia. There speaks not the reason of the Southwest but the voice of Joseph McCarthy. We do not impugn Senator Goldwater's honesty. We sincerely distrust his factionalism and his capacity for judgment.