The Gay Teen-Boy Romance Comic Beloved by Women in Japan

Moto Hagio's Heart of Thomas series markets a male homosexual love story to women—and it works.

At first glance, Moto Hagio's classic Japanese manga (or comic) The Heart of Thomas looks suspiciously like a serialized soap opera. There are hyperbolically unrequited crushes, stolen kisses, vertiginous swoons, shocking secrets revealed, tragic death after tragic death till the protagonists can barely emote their way around all the beautiful corpses—and even, at the center of the plot, an improbable pair of distantly-related doubles, whose identical features spurn the dry touch of genetics for the sweeping caress of melodrama.

There is one thing, though, that definitively and obviously sets Heart of Thomas apart from daytime serials. Hagio's story is set in a German boarding school. In case the implications aren't clear, that means that all the characters are boys, and all the romances are gay.

The Heart of Thomas is, in fact, one of the seminal works in the boys' love subgenre of shojo manga (manga for girls). Boys' love manga are manga that feature male homosexual romance, written (mostly) by women, (mostly) for women. Today in Japan, the genre is well established and popular, with hit series including Gravitation (with half a million copies sold, and that's not counting the anime adaptation) and Antique Bakery (which spun off into an anime series, a live-action TV drama, and a live-action Korean movie). In 1974, though, when Hagio began serializing Heart of Thomas, boys' love was experimental and even in some sense avant garde. The first story in the genre had just been published in 1971 by Hagio's roommate, Keiko Takemiya.

For mainstream American audiences, of course, the genre remains unfamiliar—and as such, it tends to provoke a certain amount of befuddlement. Gay romance comics for women? What? Why?

In his introduction to Fantagraphics new (and first official English) translation of Heart of Thomas, Matt Thorn offers a couple of explanations. One is historical; Hagio was directly inspired by the tragic romanticism of Jean Delannoy's 1964 filmLes amities particuliéres, about two boys who fall in love at a boarding school. But Thorn also suggests that there were formal and thematic reasons for the choice. Hagio actually initially tried to set the story in a girls' boarding school—but found that she ended up wanting to make the action, as Thorn says, too "realistic and plausible." The result was, in Hagio's words, "sort of giggly." Thorn concludes that "It was important that the characters be Other in order for Hagio to explore the themes, some quite abstract, that she wanted to explore."

I don't disagree with Thorn's analysis of Hagio's motivations, but I think it's worth thinking a bit more about why and how it's important for the characters in Heart of Thomas to be Other, and why that would be something women respond to. Specifically, I'd argue that a big part of the appeal of setting the comic at a boys' school is that it allows male, European characters to be objectified, just as Asian women often are in Western fiction. In a lot of ways, The Heart of Thomas is an Orientalist harem fantasy in reverse. Instead of a Westerner thinking about veiled maidens on cushions in some distant palace, the Japanese Hagio fantasizes about beautiful boys in an exotic Europe.

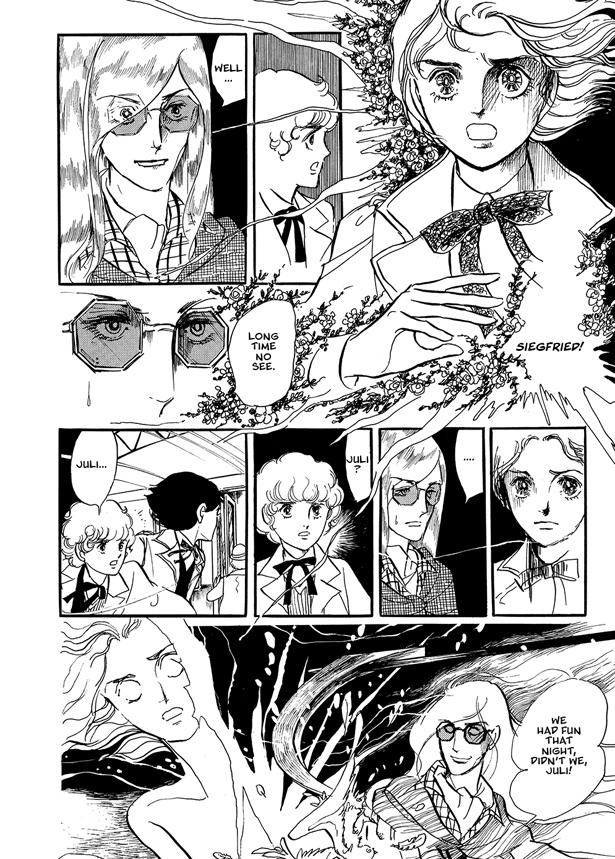

The genre of boys' love, in other words, allows Hagio and her readers to place themselves in a position of power and aggrandizement that is rare for women—as the distanced, masterful position, letting his (or her) eyes roam across variegated objects of desire. It is, then, perhaps, no accident that the villain of The Heart of Thomas—a boy named Siegfried—is distinguished primarily by his interest in the Renaissance and by his odd, octagonal glasses. Siegfried's fetishization of old Europe parallels Hagio's fetishization of contemporary Europe; his dangerous gaze parallels Hagio's dangerous gaze. And Siegfried's abuse of Juli, the protagonist, is congruent with Hagio's own stylized sexualization of her characters. His desire is her desire—and also, perhaps, the desire of her readers. Thus, the prurient fan-service which is usually doled out only to men is here explicitly taken up by women, who get to watch more exotic male bodies than you can shake a spectacle at.

But while Hagio may be Siegfried, she isn't only Siegfried. Rather, the primary emotional point of identification in the book is Juli, or, more precisely, Juli's trauma. That trauma is, again, sexual trauma—or rape. In this sense, the book does not emphasize, or insist on the distance between characters and author or audience. Instead, Juli's rape emphasizes the universality what is often presented as a particularly female experience. Similarly, Juli's shame, his self-loathing, and his tortured effort to allow himself to love and be loved, are all character traits or struggles which are often stereotyped as feminine. The fact that Juli is male seems, then, not an aspect of otherness, but rather a way to underline his similarity to Hagio and her audience. If readers can with Siegfried experience distance as mastery, with Juli they experience an empathic collapse of distance so powerful it erases gender altogether.

For Hagio, in other words, bodies seem less important than the emotions that fill and connect them. This is the logic behind the manga's central conceit. In the opening pages of the story, a young student named Thomas Werner throws himself from a bridge because of his unrequited love for Juli. Shortly thereafter, another boy named Eric Fruehling transfers to the school. It just so happens that Eric looks almost exactly like Thomas.

Hagio takes care to show us that Eric and Thomas are not the same person. Thomas was feminine and loving and docile and kept his room neat; Eric is a firebrand and expert fencer who gets in fights and breaks things. When Thomas' parents offer to adopt him, Eric spurns them, insisting that he's not their son and doesn't want to be their son.

Yet, no matter how he protests, Eric can't really distance himself from Thomas. The dead boy's emotions and memories and relationships remain with those he left, and Thomas steps into them whether he will or not. Soon he is trying, as Thomas did, to win Juli, less for his own sake, than for Juli's own. Eric then, becomes, in some sense, the heart of Thomas—the love that stays behind when the body is gone.

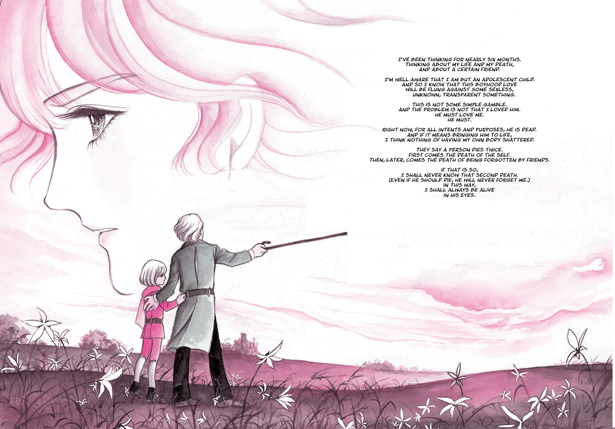

One of the first pages of the manga—a double-page spread, summarizes Hagio's themes and methods.

The text here is by Thomas, written before he died; the image is ambiguous and ambivalent. The child seems to be Thomas, standing beside an older man who is ... who? His father? Juli as an old man? Thomas himself as an old man? The giant face in the clouds is also Thomas... but two Thomas' together like that also insistently suggest (on re-reading) that one of them is, or could be, Eric. "They say a person dies twice" the note reads, "first comes the death of the self, then later the death of being forgotten by friends." Eric, then, seems like a memory—and that memory, the life after death, is emphasized by the comics form itself, in which the same image is drawn over and over, the self and its echo as self, each character a ghost ever returning.

The boys' love genre, then, freed Hagio and her audience to cross and recross boundaries of identity, sexuality, and gender. The reader can be both sexual aggressor and victim; both self and other; both gay and straight; both male and female. Bodies and character flicker in and out, a sequence of surfaces, tied together less by narrative than by the heightened emotions of melodrama—jealousy, anger, trauma, desire, friendship, and love in the heart of Thomas.