A new US edition of Mark Twain's classic novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is to be published with a notable language alteration: all instances of the offensive racial term "nigger" are to be expunged.

The word occurs more than 200 times in Huckleberry Finn, first published in 1884, and its 1876 precursor, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which tell the story of the boys' adventures along the Mississippi river in the mid-19th century. In the new edition, the word will be replaced in each instance by "slave". The word "injun" will also be replaced in the text.

The new edition's Alabama-based publisher, NewSouth books, says the development is a "bold move compassionately advocated" by the book's editor, Twain scholar Dr Alan Gribben of Auburn University, Montgomery. It will have the effect, the publisher claims, of replacing "two hurtful epithets" in order to "counter the 'pre-emptive censorship' that Dr Gribben observes has caused these important works of literature to fall off curriculum lists worldwide."

Gribben said he had decided on the move because over decades of teaching Twain, and reading sections of the text aloud, he had found himself recoiling from uttering the racial slurs in the words of the young protagonists. "The n-word possessed, then as now, demeaning implications more vile than almost any insult that can be applied to other racial groups," he said. "As a result, with every passing decade this affront appears to gain rather than lose its impact."

"We may applaud Twain's ability as a prominent American literary realist to record the speech of a particular region during a specific historical era," Gribben added, "but abusive racial insults that bear distinct connotations of permanent inferiority nonetheless repulse modern-day readers."

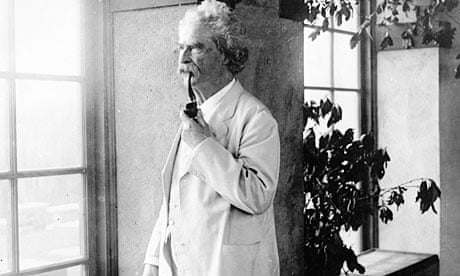

Twain himself was a passionate critic of American racism, and donated money to a number of civil rights organisations including the nascent NAACP, as well as ironically critiquing prejudice in both Huckleberry Finn and the later novel Puddn'head Wilson. But controversy over his language is not new: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn came in fifth on the American Library Association's list of the most "banned or challenged" books in the US in the 1990s (it had dropped in the 14th spot by the 2000s).

But the idea of changing the language in the novel in order to boost its popularity is still viewed with bafflement in many quarters. Dr Sarah Churchwell, senior lecturer in US literature and culture at the University of East Anglia, said the development made her "incandescent" with anger. "The fault lies with the teaching, not the book. You can't say 'I'll change Dickens so it is compatible with my teaching method'. Twain's books are not just literary documents but historical documents, and that word is totemic because it encodes all of the violence of slavery. The point of the book is that Huckleberry Finn starts out racist in a racist society, and stops being racist and leaves that society. These changes mean the book ceases to show the moral development of his character. They have no merit and are misleading to readers. The whole point of literature is to expose us to different ideas and different eras, and they won't always be nice and benign. It's dumbing down."

Geff Barton, head of King Edward's School in Bury St Edmunds, described the idea of changing Twain's language as "slightly crackpot". "It seems depressing that we are so squeamish that we can't credit youngsters with seeing the context for texts. Are we going to teach a sanitised version of The Merchant of Venice? What I would want to do is to explore issues of how language changes in context and culture," he said. Barton added that if Twain was taught less in the UK now, it was because since the national curriculum was introduced in 1989, the emphasis in English teaching was largely on works from the English literary canon rather than from America. "While we still teach To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men, Twain might just have fallen under the radar," he said.|

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion