Take a stroll down the central Chinese city’s Fan Lake Road or Fruit Lake Street and despite their names you won’t see any large bodies of water – unless it has been raining very hard, that is.

Wuhan was once known as “the city of a hundred lakes”. It had 127 lakes in its central area alone in the 1980s, but decades of rapid urbanisation mean only around 30 survive.

Located at the merging of the Yangtze and Han rivers, this low-lying city, the capital of Hubei province, has always been prone to floods, especially in the summer monsoon months. The street names are often the only reminder of the lakes and pools that been filled in and built over, but in 2016, after a week of torrential downpours, they filled with water again.

As metro stations and roads flooded, 14 people died and some urban communities were temporarily cut off from the rest of the city. The economic cost was estimated at 2.3bn yuan (£263m).

The authorities blamed poor drainage and said Wuhan’s low-lying geography made it hard for storm water to be discharged into the Yangtze when water levels in the river were high. Many locals blamed the loss of the city’s lakes.

Q&AWhere are the next 15 megacities?

Show

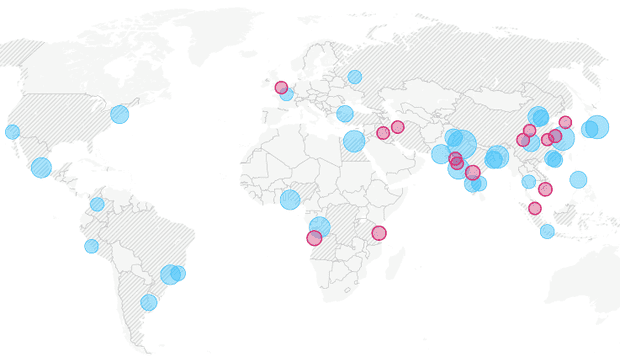

By 2035 another 15 cities will have populations above 10 million, according to the latest United Nations projections, taking the total number of megacities to 48.

Guardian Cities is exploring these newcomers at a crucial period in their development: from car-centric Tehran to the harsh inequalities of Luanda; from the film industry of Hyderabad to the demolition of historic buildings in Ho Chi Minh City.

We'll also be in Chengdu, Dar es Salaam, Nanjing, Ahmedabad, Surat, Baghdad, Kuala Lumpur, Xi'an, Seoul, Wuhan and London.

Read more from the next 15 megacities series here.

The 2016 floods were a wakeup call. With the latest UN figures projecting Wuhan’s population will exceed 10 million by 2035, the situation remains critical.

The year before the floods, Wuhan had been declared one of the country’s first 16 “sponge cities” – areas piloting ecologically friendly alternatives to traditional flood defences and drainage systems. The pace of that project has been accelerated, with a total of 228 projects in the two pilot districts of Qingshan and Sixin to retrofit public spaces, schools and residential areas with sponge features. More than 38.5 sq km of the city has been retrofitted so far, at a cost of 11bn yuan.

Nanganqu Park, which lies in the east near a large iron and steel company, was a dirty drainage ditch in the 1980s. It became a park in the 1990s and was last year transformed into a “sponge site”, with permeable pavements, rain gardens, grass swales, artificial ponds and wetlands. The idea is that these features absorb excessive rainfall through soil infiltration and retain it in underground tunnels and storage tanks, only discharging it into the river once water levels there are low enough.

“The air is always fresh here,” says retired electrical engineer Liao Baozheng as he walks in the park. “In Wuhan’s scorching summer, it’s cooler here as the lush vegetation brings down the temperature by two or three degrees.”

Under the sponge city scheme, Wuhan and the other participating areas must ensure that 20% of their urban land includes sponge features by 2020, with a target of being able to retain 70% of storm water. For Wuhan that equates to just over 170 sq km of a total urban area of 860 sq km, and last year the sponge projects were rolled out to a further nine districts.

The nationwide programme has been expanded to cover 30 cities. By 2030, participants must ensure that 80% of their urban land includes sponge features.

Wen Mei Dubbelaar, director of water management at Arcadis China, which is working as a consultant to Wuhan’s water department on sponge city projects, says the key is to “give space back to the river … [instead of] fighting the water”.

“Rain gardens, grass swales and low elevation green belt are a low-impact way of creating more space to catch the rainfall,” she says. “They’re particularly suitable for Wuhan because the city has a relatively high level of groundwater and it is almost impossible to let the water seep underground.”

Retrofitting old residential communities is a particular challenge because there is little space left for construction and existing drainage systems are often outdated and worn out. Such projects can be eye-wateringly expensive. Transforming the 3.8 sq km Nanganqu site involved a total investment of 1.26bn yuan, through a public-private partnership where 20% of the funds came from city government and the rest from the private sector – in this case the iron and steel company that built the affected residential areas for workers in the 1970s and 80s.

Central government subsidies for the sponge cities projects are only set to last until 2020, so scaling up the scheme to cover 80% of the city by 2030 will be a “huge burden” unless the local government finds ways to involve more private investors, says Dr Faith Chan, assistant professor in geographical sciences at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China. “One possible way is to involve real estate developers, because such sponge sites do help increase the value of the land.”

Even if the sponge city projects are fully implemented, this emerging megacity faces severe challenges.

“There are no golden standards, but cities like Tokyo and Singapore could handle one-in-100-year storms,” Chan says. “In China, most drainage systems are [currently] designed to deal with at most a one-in-10-year storm. Once the sponge city projects are complete, Wuhan should be able to handle a one-in-30-year storm.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion