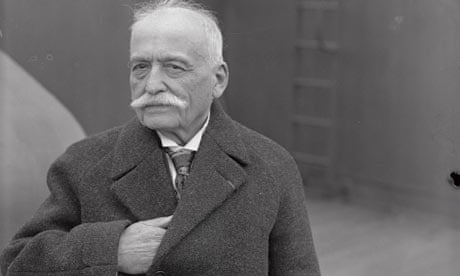

In a letter today to the Guardian Egon Ronay compares Gordon Ramsay unfavourably to César Ritz (1850-1918), the best-known inn-keeper in history and Auguste Escoffier (1849-1935), the most celebrated chef who ever lived.

Escoffier codified the food served in establishments such as his own Savoy Hotel restaurant. From his "Le Guide Culinaire" any chef could learn the correct basic preparation and garnish of the hundreds of dishes that constituted classic haute cuisine. He is a hero to today's chefs, because he preached the maxim that became today's kitchen mantra, "faites simple", and actually put it into practice, rediscovering the fumets and reductions of ancient French cookery that are the basis for today's lighter sauces.

So Escoffier appears to be a good candidate for the chef as champion. The only difficulty is that he and Ritz were crooks. Escoffier himself was chiefly guilty of taking bribes and kickbacks from suppliers (then a common practice, as it may still be in some big institutions). But there were huge sums involved – not much short of £1m in today's money. Mr Ronay neglects to mention that Escoffier and Ritz were sacked by their employers at the Savoy on 28 February, 1898.

The first appearance of this historic fact was a remark in Ann Barr's and my 1984 "The Official Foodie handbook," which was expanded in an article by me originally published in both the Observer and The Wall Street Journal. I had in my possession copies of signed confessions by Ritz and Escoffier. These had evidently come from the archives of the Savoy and I had received them anonymously, simply left on my desk at The Observer in late 1983. When I first published their contents, I called my informant "Deep Palate." (I have only recently learned his identity - he is, amusingly enough, an artist now more celebrated than Escoffier in his heyday).

Pierre Escoffier, a retired oil industry executive and grandson of Escoffier, having read the account in The Official Foodie Handbook, challenged me to authenticate Deep Palate's papers or retract my allegations. I then applied pressure to the Savoy management by giving them a deadline after which I would publish the contents of the (fairly obviously purloined) documents. At the eleventh hour I was summoned to the boardroom of the Savoy by Sir Hugh Wontner, then the Savoy Group's chairman, who confirmed the authenticity of the documents. Before I sent copies of the confessions and supporting evidence to him, he said, he had never actually seen the material, which was still in the hotel's archives. Sir Hugh told me that the matter of the scandal, however, was well known to those working in high positions in the Savoy, though never talked about. When I asked him who had told him, he said "it was in the walls" of the hotel itself.

In the confessions dated 29 January 1900 Ritz, and their head waiter, Louis Echenard, though they denied "that they have ever been guilty of appropriating or applying to their own us the monies of the Savoy Hotel Company, or taking money by way of presents or commissions from the tradesmen of the Hotel," did pay the sum of £4,173, plus another £6,377 from Ritz, to make up for the "astounding disappearance of over £3,400 of wine and spirits in the first six months of 1897" as well as "the wine and spirits consumed in the same period by the Managers, staff and employees amounting to £3,000." Ritz and Echenard confessed, in all, to 15 counts of wrongdoing.

They also admitted that they had known about, and not prevented, Escoffier from doing precisely what they denied having done themselves – accepting "commission", gifts and kickbacks from the Savoy's suppliers amounting to over £16,000. The Savoy managed to recover half this sum (£8,087) from the tradespeople, and Escoffier consented to a verdict against him for the other half, but being "without means and unable to pay" offered £500 in cash, which was accepted. The tradesmen's testimony against Escoffier had included the allegation that "Mr Escoffier always had a regular 5% commission" from Messrs Hudson Brothers, grocers on the Strand. Besides this, "which was common knowledge in the shop, large presents consisting of packages of goods were sent every week addressed to Mr Boots, Southsea."

Why were the goods wanted in Southsea? Did the great chef, who lived most of his working life in different country from his wife, Delphine, and their children, perhaps have a second family in Southsea?

The amount of money involved was not trivial, though Ritz accounted for a much larger sum than Escoffier. What most annoyed the board of the Savoy was that the pair had charged the Savoy for food and drink used during negotiations and business meetings for Ritz's next venture, the rival Carlton Hotel, opened in 1898 on the corner of Haymarket and Pall Mall (now the site of New Zealand House). Ritz had got away with much of the planning for this brand new hotel because he had insisted, when he joined the Savoy in 1889, that his contract allow him to conduct his own business for six months of each year. But this did not, the Savoy board felt, entitle him to entertain potential investors in the Carlton at the Savoy's expense.

The board first became suspicious in 1895 when, though overall receipts increased greatly, the profits from the kitchens fell, and in 1897, the kitchen actually showed a loss. On the 28th of February 1898, after taking advice from the Rt Hon. Edward Carson, the most eminent lawyer of the day, the auditors informed the directors of the Savoy that they had a fiduciary duty to sack Ritz, Escoffier, Echenard and one other member of the staff.

With incredible chutzpah (born of the successful suit for breach of contract brought by Ritz's predecessor, Hardwicke) Ritz and Escoffier prepared a counterclaim for wrongful dismissal. This meant that the Savoy had to carry out a full investigation of the charges, depose witnesses and examine the relevant accounts. The documents in my possession included parts of these proceedings. The result was that on 3 January 1900 the malefactors made signed confessions, admitting to actual criminal acts, including fraud.

However, no charges were ever brought, and the documents were never used or made public in any way. I can guess at the reason. During his time at the Savoy, Ritz had played pander to the Prince of Wales and Lillie Langtry. The Prince naturally moved his custom with Ritz to the Carlton in 1898 (he'd have opened himself to blackmail if he hadn't). Had the matter come to the courts, the Prince of Wales would have been involved in yet another scandal, and the old queen, then 80, would certainly come to know of it and be distressed. That, I believe, is why the gentlemen of the Savoy were content simply to deposit the findings of their "Committee of Investigation" and the resulting confessions in the archives and call it a day.

By 1901, when the Carlton became the social headquarters for the coronation of Edward VII, Ritz, who had what we'd now call bipolar disease, had broken down completely. There was no point in proceeding against him. Escoffier's glory days were over. Never good with money, all his business ventures had failed. He supported and educated a huge extended family, and died in 1935 in Monte Carlo, leaving almost nothing. Was he supporting a Mrs Boots and some little Boots? Was he a gambler? Nobody knows.

As an idol, Escoffier has feet of clay. And we should remember he was sacked "for the usual reasons." Those haven't changed much either. Never mind the F-word, I think Gordon Ramsay's business practices stand up remarkably well by comparison, don't you?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion