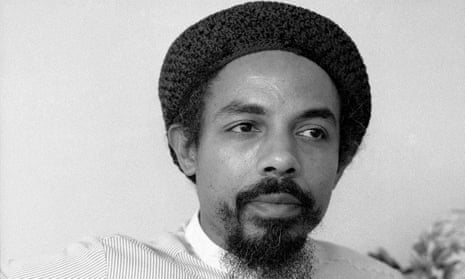

Jalal Mansur Nuriddin – sometimes known as “the grandfather of rap” – who has died aged 73 of cancer, was born on 24 July 1944 in New York, growing up in the Fort Greene area of Brooklyn. He never told me his birth name, but he was professionally known as Alafia Pudim when he co-founded the legendary proto-rap outfit the Last Poets in May 1968, with fellow poets Omar Ben Hassan and Abiodun Oyewole, and percussionist Nilijah.

Rarely do you encounter an artist who Miles Davies respected. In his autobiography Miles wrote: “I used to love poetry, especially the black poets, the Last Poets, LeRoi Jones – Amiri Baraka.” Or as Quincy Jones stated in his autobiography: “This mix of elements – what people now label rap – first came on my radar screen in the 1960s, with performers like the Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron.”

The Last Poets signed to Douglas Records after Jimi Hendrix producer Alan Douglas heard them perform on a basketball court in Harlem – a prelude to what later became the famous block parties associated with DJ Kool Herc, where rap mixed with DJing to coalesce the hip-hop sound originally forged by the Last Poets. Douglas released their self-titled first album to critical acclaim in 1970, with the hit record Niggers Are Scared of Revolution – it established the Last Poets as the artistic vanguard of the civil rights movement, in the wake of the deaths and incarceration of so many of the black activist leaders in America, such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and the Black Panthers. People turned from the political leaders to the Black Arts Movement for their guidance in the early 70s – another such luminary was a young Gil Scott-Heron, who met them when they performed at Lincoln University, where he was studying. Gil wrote his seminal piece The Revolution Will Not Be Televised as a response to the Last Poets’ When the Revolution Comes, from that first album.

In 1971 Douglas released their second album, This Is Madness. He wanted to release a classic “jail toast” – poetry by prisoners with rudimentary percussion – that Jalal had written called Hustlers Convention. Jalal had learned to toast while in prison – he never told anyone how he ended up there, only that he’d run the streets of Brooklyn with a gang called the Fort Greene Chaplains, who often fought with rivals the Bed-Stuy Bishops – but he was offered early release if he joined the army amid the Vietnam war draft. Jalal accepted and trained as a paratrooper. True to his revolutionary spirit, he refused to salute the flag while on parade one day, in protest at the war, got into a fight and got locked up again in the army jail. Like Malcolm X had done when he was drafted, he convinced them that he was a bit unhinged: he was given an honourable medical discharge and took a job as a stenographer in a Wall Street bank.

He came to realise how the markets, bankers and brokers were far more prolific hustlers than any he’d seen on the streets and was inspired to write Hustlers Convention (1973) – it follows the exploits of two hustlers, Spoon and Sport, as Jalal characterised what he saw was wrong with life on the streets. The Mean Machine (1971), meanwhile, was an epic rap about modern life, characterised as a series of mechanised elements fused together to deceive mankind into behaving how the government wants them to, through technology, media and advertising. The classic lines “automatic push button remote control, synthetic genetics command your soul” were sampled in MARRS’s Pump Up the Volume. Jalal also recorded another jail toast with Jimi Hendrix called Doriella Du Fontaine, which he refused to release after Hendrix’s death because he “didn’t want to capitalise on Jimi”. Douglas did however release it in 1984 under another of Jalal’s aliases, Lightnin’ Rod.

After converting to Islam, he changed his name from Alafia Pudim to Jalal Mansur Nuriddin (which is Arabic for “glorious and victorious light of the faith”). By 1973 the band had split, and Omar and Abiodun left. That year Jalal was joined by poet Sulaiman El Hadi, and the Last Poets emerged from proto-rap, using poetry over tribal percussive beats, to an all-out band with spoken word at its core. Their third album, Chastisement, evolved from black nationalism towards a more Islamic vibe, the album being reflective of their Muslim beliefs, but it also introduced a concept Jalal called “jazzoetry” – a big subsequent influence on Gilles Peterson and the acid jazz scene – and numerous other albums came in its wake.

The music on Hustlers Convention had included several jazzy tracks by Kool and the Gang. After a dispute with Kool’s label, United Artists (through whom Douglas had released the album) withdrew Hustlers Convention, but after being re-released by Melle Mel – member of early rap group the Furious Five – it became the foundation of modern day hip-hop. Ice-T once said, “I wasn’t the first rapper, but I bet the first rapper heard Hustlers Convention”; the Last Poets made a brief reunion in 1994 to make a cameo in the John Singleton film Poetic Justice, apparently at star Tupac Shakur’s request.

I first met him when he was in London in 1984 – after which he became a Liverpool resident for many years, before his self-imposed exile continued in Paris from 1996 until Obama took office – and in 1992 he asked me to manage him. I agreed, and in the course of our friendship I became a Muslim at his guidance – he named me Malik, and in 2003 we went on a pilgrimage to Mecca together. When I heard of his illness last year, I travelled to Atlanta to spend a few days with him in the holy month of Ramadan.

One day Jalal related to me that he wanted to write his “whole life story in rhyme”. I jokingly said: “Oh man, you’ll be dead before you write that book.” He later told me that he took that comment to heart and he set about the mammoth writing project, which he finished only last year. What Jalal wrote became the sequels to Hustlers Convention called The Hustlers Detention and The Hustlers Ascension, which collectively form a three-part autobiography written entirely in rhyme. The latter two, though completed, remain unpublished at the time of his death.

Jalal has been my friend, my mentor and, in many respects, my saviour. Without him, I wouldn’t be who I am today. His legacy will be the spiritual, uplifting words that he has shared with us, that have changed so many lives in his remarkable 50-year career, not least of which is my own. My sincere condolences to his children, Ahmad (Ibn), Yasmin, Azizeh, Bukhari, Jamillah, Tariq, Tariqah, Sadja, Sophia, Soraya and his stepdaughter Lucy and his wider family in the US, UK and France. Rest in power and peace my dear brother – you will never be forgotten.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion