In December, I went to see Neon Indian play in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. They were great, the spangled kitschadelic wooze of their Psychic Chasms LP so much more imposing live than on record. But I was actually struck even more by support band Tiger City. Not because they were amazing or anything, but because, while clearly an indie band, they sounded for all the world like Go West: they had that tight, slick mid-80s pop-funk sound down pat, the singer flexed a supple falsetto in the Daryl Hall blue-eyed soul mould, and the net effect was like time travel to 1986. Yet in an article on the web I found the day after the gig, Tiger City are described as "entrenched members of Brooklyn's underground rock scene". Not only did all this underline the meaninglessness of the word "indie" nowadays, it reminded me of the endless, endless 1980s revival that has run the entire course of the noughties. Perhaps, now we've reached the point where hipster bands strive to sound like Then Jerico and Robert Palmer, it's finally run its course?

Every decade seems to have its retro twin. The syndrome started in the 1970s, with the 1950s rock'n'roll revival, and it continued through the 1980s (obsessed with the 1960s) and the 1990s (ditto the 1970s). True to form, and right on cue, the noughties kicked off with a 1980s electropop renaissance. Separate, but running in parallel, was the rediscovery of post-punk and mutant disco launched by countless artists: LCD Soundsystem, the Rapture, DFA, Bloc Party, Interpol, Franz Ferdinand, Liars ... there's really far too many to mention.

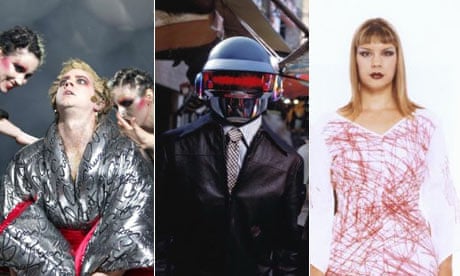

On the subject of post-punk, I've probably said enough really, don't you think? (I will mention in passing that one reason Tiger City opted for the Hall & Oates/Go West superslick sound was that other New York bands had worn the "scratchy post-punk guitar sound" threadbare). But the nu-wave/neo-electro craze, being one of the more amusing upshots of the early part of the noughties, deserves reconsidering. Eighties flavours had already been circulating on the underground dance scene for a few years prior to 2000: there was a loose network of electro-influenced outfits like Adult, Dopplereffekt, Les Rythmes Digitales, I-f (of Space Invaders Are Smoking Grass fame), and more. Daft Punk took these traits into the mainstream with 2001's Discovery, revered by many as the greatest album of the noughties. Melding influences from the early 1980s but also the late 1970s (post-disco club styles, synth-pop, electro, Supertramp/ELO-style soft-rock, Van Halen-esque snazz-metal), they created a sound of transcendent artificiality.

What makes Discovery seem "1980s" is the way Daft Punk tapped into that decade's association with "plastic pop". At the time, this was something that indie rock resisted, by rejecting synths for guitars, valorising noise and dirt or taking up rootsy, woodsy influences from folk and country, and singing with an all-too-human snarl or mumble. Coming from an indie background themselves (their name derived from a negative review in Melody Maker), Daft Punk took the dialectical next step and transvaluated "plastic": they shed its negative associations (synthetic, fake, disposable, inauthentic) and recovered its original utopian aura (the idea of plastic as the material of the future).

Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter's use of vocoder was crucial here, coating their voices in an angelic, otherworldly sheen. But this was actually a form of false memory syndrome: apart from certain Kraftwerk songs and the breakdance-oriented electro tracks they inspired, vocoder and other robotic voice treatments weren't widely used in the real 1980s. The hallmark of original synth-pop was its emotional, at times operatic singers: the torrid, teetering off-pitch Mark Almond, soulful Aretha-wannabes such as Alison "Alf" Moyet and Annie Lennox. Discovery's plastique fantastique fiction of the 1980s would nonetheless be hugely influential, popping up in unlikely places across the decade, from Kanye West's Stronger (based on Harder Better Faster Stronger) to the Pennsylvania indie-psych outfit Black Moth Super Rainbow, whose vocoder-tastic Dandelion Gum was my fave LP of 2007.

Daft Punk's own follow-up, Human After All, overdid the mandroid shtick with tracks like Robot Rock and flopped. But it seems only righteous that they have scored Tron Legacy, the forthcoming sequel to the quintessentially 1980s science-fiction movie.

When Discovery came out, a full-blown new romantic revival was emerging from the hipster precincts of Brooklyn, Berlin and London. Clubs like Trash and Berliniamsburg were packed with svelte young poseurs sporting a nu-new wave look of assymetrical haircuts, skinny ties worn over T-shirts, and studded bracelets. Heavily influenced by the cult 1982 movie Liquid Sky, the Berliniamsburg scene called itself "electroclash". Impresario Larry Tee organised the first Electroclash festival in Autumn 2001, featuring acts like Peaches, Chicks On Speed, and Fischerspooner. But while the latter were signed for a reputedly massive advance and other outfits like ARE Weapons, Tiga, Crossover, and Miss Kittin were much buzzed about, none of the groups had the hook power or vocal presence to match 1980s ancestors like Gary Numan. Ironically, given that the scene was a reaction against the "faceless techno bollocks" of 1990s rave, the most memorable electroclash anthems were stirring, majestic instrumentals by faceless producers like Vitalic and Legowelt.

Electroclash went from Next Big Thing to Last Little Fad within a year. But it didn't go away, it just slipped on to the noughties pop-cult backburner, biding its time as a staple sound in hipster clubs. By mid-decade the "clash" was long gone; people just talked about "electro". This was confusing for those of us who'd been around in the actual 1980s and for whom "electro" meant something specific: that Roland 808 bass-bumping sound purveyed by Afrika Bambaataa and Man Parrish, music for bodypopping and the electric boogaloo. In the noughties, electro came to refer to something much more vague: basically, any form of danceable electronic pop that sounded deliberately dated, that avoided the infinite sound-morphing capacities of digital technology (ie the programs and platforms that underpinned most post-rave dance) and opted instead for a restricted palette of thin synth tones and inflexible drum machine beats. "Electro" meant yesterday's futurism today.

Then abruptly, unexpectedly, at the opposite end of decade, electro took off. It left behind the Shoreditch trendoid zone so acutely/affectionately satirised by the Mighty Boosh and took over the charts with the synth-girl wave of La Roux, Lady Gaga, and Little Boots. Of all of them, Gaga was the most electroclash-indebted. Her image games, her line of patter, and her little plastic penis echoed the pro-pretentiousness/"against nature" rhetoric of Fischerspooner, the drag queeny fabulousness of Berliniamsburg faves like Sophia Lamarr, the glitz 'n' glamour fantasies of Miss Kittin (who had monotoned with icy hauteur on Frank Sinatra about "sniffing in the VIP area"). Everything about Gaga came from electroclash, except the music, which wasn't particularly 1980s, just ruthlessly catchy noughties pop glazed with Auto-Tune and undergirded with R&B-ish beats.

Artifice and retro-futurism had been a big part of Daft Punk's self-presentation, from the Robocop helmets to the anime-style videos for the singles from Discovery. But there was nothing cool or camp about their music: it burst with rhapsodic emotion. Shrugging off notions of retro and irony, Bangalter said that Discovery was "less of a tribute to the music from 1975 to 1985" than a flashback to the blissfully indiscriminate way they listened as children to the radio during those halcyon years: "When you're a child you don't judge or analyse music … You're not concerned with whether it's cool or not." As such Discovery anticipated a quite different uptake of 1980s pop that would occur in the second half of the noughties: the ecstatically blurry and irradiated style of indie that's been dubbed "glo-fi". Compare Bangalter's remark with glow-fi godfather Ariel Pink, who says his pop sensibility comes from watching MTV incessantly from the age of five onwards (ie only a couple of years after the channel was launched in 1981). Pink went so far as to describe MTV as "my babysitter". As a result, on the many recordings he's issued under the name Ariel Pink's Haunted Graffiti – two of which, Worn Copy and The Doldrums, are among my favorites of the decade – his reverb-hazy neo-psychedelic sound is haunted by the friendly ghosts of Hall & Oates, Men Without Hats, It's Immaterial, Blue Oyster Cult, Rick Springfield. It's an approach to songwriting and melody he assimilated as an ears-wide-open child.

Originally discovered by Animal Collective for their label Paw Tracks, but recently signed to 4AD, Ariel Pink has turned out to be one of the decade's most influential indie musicians. His progeny and his allies include blog-beloved artists like Gary War, John Maus, Nite Jewel, Tape Deck Mountain, Washed Out, Memory Cassette, Ducktails, and many more. Indeed, combine Ariel Pink's Haunted Graffiti and Daft Punk and you pretty much get the sound of Neon Indian. Elsewhere in the glo-fi zone, other "1980s" seep into the mix: new age synth (the cosmic drone epics of Oneohtronix Point Never), 4AD-style Goth-lite (Pocahaunted sound like a Burning Man Dead Can Dance). Another 1980s-invoking hallmark of the new sub-underground is its cult of the cassette. Tape has a double association here. On the mass level, it was the 1980s quintessential format: far more than the CD, it was the way most kids would have owned music. But cassettes were also the preferred means of dissemination for underground 1980s scenes like industrial and noise. Tape was the ultimate in do-it-yourself, because they could be dubbed-on-demand at home, whereas vinyl required a heavier financial outlay. Today's post-noise microscenes like glo-fi maintain the tape trade tradition, releasing music in small-run editions as low as 30 copies and wrapping them in surreal photocopy-collage artwork.

Electro and glo-fi don't exhaust the 1980s-into-noughties topic by any stretch. I already mentioned post-punk, the decade's big retro bonanza. When that seam started to become exhausted, indie bands began probing more obscure crannies of the Thatcher-Reagan decade, such as C86 and Italo disco and minimal synth, while 1980s synth-funk and vintage videogame sounds are rife in dance music from 8-bit to wonky to skweee.

As someone who lived through the 1980s – it was the first decade I was pop-conscious and alert all the way through, from start to finish – it's enjoyably disorienting to observe all these distortions and retroactive manglings of the period, from the vocoder fetish to the fact that I really don't recall terms like "Italo disco" or "minimal synth" having any currency whatsoever back in the day. But what's also interesting is how much of the era has yet to be rediscovered or recycled: the Membranes/Bogshed style shambling bands, the Redskins-style soulcialists, goth, Waterboys/Big Country-style Big Music, and a half-dozen other scenes and genres. But hey, it's 2010, the first year of the new decade, which means that – according to the 20-year rule of revivals – we really need to get started on the 1990s.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion