Scientists have managed to reconstruct the route by which HIV/Aids arrived in the US – exonerating once and for all the man long blamed for the ensuing pandemic in the west.

Using sophisticated genetic techniques, an international team of researchers have revealed that the virus emerged from a pre-existing epidemic in the Caribbean, arrived in New York by the early 1970s and then spread westwards across the US.

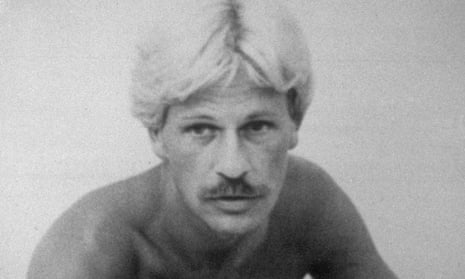

The research also confirms that Gaétan Dugas, a French-Canadian flight attendant, was not the first person in the US to be infected, despite being dubbed “Patient zero” in a study of gay men with Aids in 1984. Based on that study, author Randy Shilts named Dugas in 1987 and wrote that “there’s no doubt that Gaëtan played a key role in spreading the new virus from one end of the United States to the other.”

Characterised by Shilts as promiscuous and irresponsible, Dugas – who died of Aids in 1984 after assisting with studies into whether it was caused by a sexually transmitted agent – was widely vilified.

However, analysis of Dugas’s HIV genome from a blood sample shows that it was typical of strains of the virus within the US at the time and was not the root from which the virus diversified in North America.

The findings, the authors say, tie in with a large body of evidence that shows that Dugas was not the source of the pandemic in North America, and that the mistake may have been the result of a typing error in the original study that referred to Dugas as “Patient 0” – a term now widely used to mean the first case of an outbreak – instead of “Patient O”, the capital letter, which merely indicated that he lived outside California.

“The current study provides further evidence that patient 57, the individual identified both by the letter O and the number 0, was not patient zero of the North American epidemic,” said Richard McKay, historian and co-author of the study from the University of Cambridge, adding that the authors of the original study had already pointed out he was unlikely to be the source. He said a “trail of error and hype” had led to Dugas being branded with the “Patient Zero” title.

“Gaétan Dugas is one of the most demonised patients in history, and one of a long line of individuals and groups vilified in the belief that they somehow fuelled epidemics with malicious intent,” said McKay.

“In many ways the historical evidence has been pointing to the fallacy of this particular notion of patient zero for decades,” said McKay. “This individual was simply one of thousands infected before HIV/Aids was recognised.”

Writing in the journal Nature, researchers from the US, UK and Belgium describe how they developed a new technique to unpick the history of HIV-1 group M subgroup B, the subtype of HIV that is most prevalent in the western world.

Called “RNA jackhammering”, the technique tackles the problem that the genetic material of HIV, which exists in the form of a single-stranded molecule known as RNA, breaks down rapidly over time, making it difficult to extract and piece together. RNA jackhammering allows scientists to selectively copy tiny fragments of the virus’s RNA and stitch them together.

Using the new approach, a technique the team say took around four years to develop, the scientists turned to serum samples that had been collected in 1978 and 1979 from men who had sex with men in New York and San Francisco - samples collected before what became known as Aids was first reported in 1981.

That they were able to painstakingly assemble the complete HIV genome from eight of the oldest-known samples, allowed the team to place them on a sort of “family tree” of the virus. Even though the number of genomes is small, the team say the eight samples not only enabled them to explore the genetic diversity of the virus in North America in the late 1970s but also chart its history, revealing the importance of New York City in the chain of events.

The level of genetic diversity, they say, shows that the virus was circulating in the US for a decade before what eventually became known as Aids was recognised.

According to the team’s reconstruction, based on the new findings as well as previous data, after jumping from non-human primates to humans in Africa, HIV spread to Caribbean countries by around 1967, with the subtype arriving in New York by 1971 and reaching San Francisco by 1976. The conclusions, they add, are also supported by the prevalence of the HIV virus among the collection of serum samples and the spread and timing of later patient cases.

“New York City looks geographically like the key turning point for the emergence of this subtype, and New York City acts as this hub from which the virus moves to the west coast somewhat later and eventually to western Europe and Australia and Japan and South America and all sorts of other places,” said Michael Worobey, co-author of the research from the University of Arizona.

The results back up previous work by the Worobey and others, who have spent years using a variety of approaches to trace the route of the HIV/Aids epidemic and emphasises that the virus travelled from the Caribbean to the US, not vice versa. But Worobey is quick to point out that the idea of culpability is misplaced.

“No-one should be blamed for the spread of a virus that no-one even knew about,” he said. “How the virus moved from the Caribbean to the US and New York City in the 1970s is an open question - it could have been a person of any nationality, it could have even been blood products.”

The mistaken emphasis placed on Dugas that saw him placed as a key link between the spread of HIV/Aids between the east and west coasts of the US in the 1984 study, he said, was likely down to Dugas’s efforts to help researchers.

“Probably what happened here was a case of a guy who was unusually helpful to investigators providing lots and lots of names of sexual contacts,” said Worobey. “He’s just one of many people who is highly sexual active and in this network of people who are popping up as early Aids cases but he ended up looking up as this central character almost certainly just because of how helpful he was.”

The case, adds McKay, also highlights the problems with trying to pinpoint the first person to be infected in an epidemic. “One of the dangers of focus on a single patient zero when discussing the early stages of an epidemic is that we risk obscuring important structural factors that might contribute to its development - poverty, legal and cultural inequalities, barriers to healthcare and education,” he said.

As well as donating blood plasma for analysis for the original study, Dugas had provided researchers with the names of 72 of the roughly 750 partners he had had a sexual relationship with in the previous three years.

“The fact that Dugas provided the most names, and had a more memorable name himself, likely contributed to his perceived centrality in this sexual network,” Dr McKay added.

Gkikas Magiorkinis, a clinical and evolutionary virologist at the University of Oxford, said that the research highlights the power of such genetic techniques in shedding light on how a virus spreads among a population. “They managed to get full sequences of viruses from old samples, and that has been very difficult up until now,” he said. That, he adds, could prove valuable for probing the history of many other viruses, including hepatitis C, and for designing better interventions. “If we want to know how we are going to stop an epidemic we need to know who infected who and how this happened, so it will have important applications with respect to controlling epidemics,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion