The following correction was printed in the Guardian’s Corrections and clarifications column, Thursday August 7 2008

Several readers have complained that in the review of the RSC’s Hamlet, below, Michael Billington quoted the prince’s opening soliloquy as saying: “O that this too too sullied flesh would melt.” “Sullied”, they objected, should have been “solid”. In fact there are three respected versions of this text. In the first quarto: “O that this too much grieu’d and sallied flesh / Would melt to nothing”; In the second quarto: “O that this too too sallied flesh would melt, / Thaw and resolue itselfe into a dewe,”; and in the first folio: “Oh that this too too solid Flesh, would melt, / Thaw, and resolue it self into a Dew”. “Sallied” nowadays is usually given as “sullied”. No version is more decisively authentic than the others. Michael Billington could not discern which one Tennant was using.

*

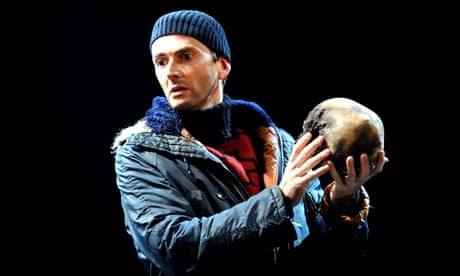

It’s a sign of our star-crazy culture that there has been months of speculation about David Tennant’s Hamlet. The big news from Stratford is that Gregory Doran’s production is one of the most richly textured, best-acted versions of the play we have seen in years. And Tennant, as anyone familiar with his earlier work with the RSC would expect, has no difficulty in making the transition from the BBC’s Time Lord to a man who could be bounded in a nutshell and count himself a king of infinite space. He is a fine Hamlet whose virtues, and occasional vices, are inseparable from the production itself.

Doran’s production gets off, literally, to a riveting start: the first thing we hear is the sound of hammering and drilling as Denmark’s night-working Niebelungen prepare the country for war. And our first glimpse of the chandeliered, mirrored, modern-dress court gives us an instant clue to Hamlet’s alienation. Patrick Stewart’s superb Claudius insultingly addresses Laertes’s problems before those of Hamlet. And, urging Hamlet not to return to university, Stewart has to be publicly reminded that Wittenberg is the place in question. Immediately we sense Claudius’s hostile suspicion towards, and cold contempt for, his moody nephew.

Tennant’s performance, in short, emerges from a detailed framework. And there is a tremendous shock in seeing how the lean, dark-suited figure of the opening scene dissolves into grief the second he is left alone: instead of rattling off “O that this too too sullied flesh would melt”, Tennant gives the impression that the words have to be wrung from his prostrate frame. Paradoxically, his Hamlet is quickened back to life only by the Ghost; and the overwhelming impression is of a man who, in putting on an “antic disposition”, reveals his true, nervously excitable, mercurial self.

This is a Hamlet of quicksilver intelligence, mimetic vigour and wild humour: one of the funniest I’ve ever seen. He parodies everyone he talks to, from the prattling Polonius to the verbally ornate Osric. After the play scene, he careers around the court sporting a crown at a tipsy angle. Yet, under the mad capriciousness, Tennant implies a filial rage and impetuous danger: the first half ends with Tennant poised with a dagger over the praying Claudius, crying: “And now I’ll do it.” Newcomers to the play might well believe he will.

Tennant is an active, athletic, immensely engaging Hamlet. If there is any quality I miss, it is the character’s philosophical nature, and here he is not helped by the production. Following the First Quarto, Doran places “To be or not to be” before rather than after the arrival of the players: perfectly logical, except that there is something magnificently wayward about the Folio sequence in which Hamlet, having decided to test Claudius’s guilt, launches into an unexpected meditation on human existence.

Unforgivably, Doran also cuts the lines where Hamlet says to Horatio, “Since no man knows of aught he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.” Thus Tennant loses some of the most beautiful lines in all literature about acceptance of one’s fate.

But this is an exciting performance that in no way overshadows those around it. Stewart’s Claudius is a supremely composed, calculating killer: at the end of the play scene, instead of indulging in the usual hysterical panic, he simply strides over to Hamlet and pityingly shakes his head as if to say “you’ve blown it now”. Oliver Ford Davies’s brilliant Polonius is both a sycophantic politician and a comic pedant who feels the need to define and qualify every word he says: a quality he, oddly enough, shares with Hamlet. And I can scarcely remember a better Ophelia than that of Mariah Gale, whose mad-scenes carry a potent sense of danger, and whose skin is as badly scarred by the flowers she has gathered, as her divided mind is by emotional turmoil.

That is typical of a production that bursts with inventive detail. I love the idea that Edward Bennett’s Laertes, having lectured Ophelia about her chastity, is shown to have a packet of condoms in his luggage. And the sense that this is a play about, among much else, ruptured families is confirmed when Stewart as the Ghost of Hamlet’s father seeks, in the closet scene, tenderly to console Penny Downie’s plausibly desolate Gertrude.

Audiences may flock to this production to see the transmogrification of Dr Who into a wild and witty Hamlet. What they will discover is a rich realisation of the greatest of poetic tragedies.

Top 10 modern Hamlets

1 Michael Redgrave (1958) The best all-round Hamlet of the last half-century, played with passion, intellect, violence and stoic resignation

2 Innokenty Smoktunovsky (1964) Brooding, smouldering and exuding a Nureyev-like charisma

3 David Warner (1965) Frail, bedecked with a long scarf and acquired pop-star status as an epitome of 1960s youth

4 Derek Jacobi (1979) Defeated the elements at Kronborg Castle

5 Michael Pennington (1980) Dissected the text with postgraduate vigour

6 Jonathan Pryce (1980) Produced the Ghost’s voice from his innards

7 Stephen Dillane (1994) A sardonic, hawk-eyed joker who stripped to the buff

8 Kenneth Branagh (1996) Full of humour and buoyant athleticism

9 Angela Winkler (2000) The latest in a long line of female Hamlets, played with tenderness

10 Simon Russell Beale (2000) A perfect Hamlet for the age of irony, expressing disgust at the surrounding corruption