On one wall of Daniel Ek's sparsely furnished office in the Stockholm headquarters of Spotify, there is a quotation from George Bernard Shaw: "The reasonable man adapts himself to the world. The unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man."

Ek, 30, doesn't immediately strike you as the unreasonable type. His face is placid, his voice mild with a transatlantic accent, his body language passive. He wears a rumpled red Ralph Lauren polo shirt, jeans and white trainers. His scalp and chin have equal amounts of stubble, which makes his head look reversible.

"I think Daniel Ek is unbelievable but I don't think you can say he's a charming guy," says Per Sundin, chairman and CEO of Universal Music Sweden. "He comes across as non-threatening in a business with a lot of big personalities," says Gustav Söderström, Spotify's chief product officer.

Seven years ago, Ek began approaching record labels with a bold proposition: to make their valuable content available to rent rather than buy, and for free. Most were understandably wary. This new product looked as if it might be the killer of the music industry rather than, as its quietly purposeful creator claimed, its saviour.

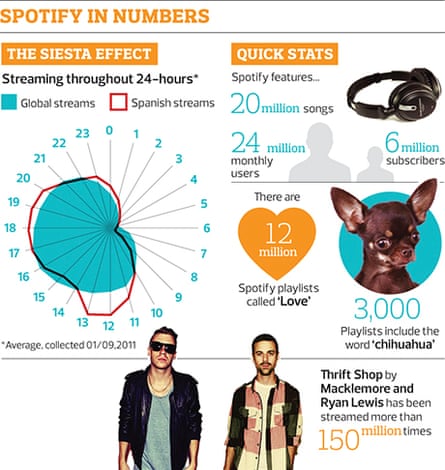

Ek won that first battle for hearts and minds. Although many rival services are available, Spotify has become synonymous with streaming, the same way Google is with searching. Last month, on the fifth anniversary of its launch, it made more than 20million songs available to 24 million users in 32 territories. Swedish newspaper Dagens Industri recently valued the company at $5.2bn. Inevitably, it has made some impassioned enemies. Radiohead's Thom Yorke recently said: "I feel like as musicians we need to fight the Spotify thing," and called the industry's support for the company "the last desperate fart of a dying corpse".

But it has also made Ek many friends. He fraternises with entrepreneurs, rock stars and other interesting, powerful folk. His next appointment after me is with dubstep star Skrillex. "I get to learn from some of the most inspiring people in the world, whether it's the Mark Zuckerbergs and Jeff Bezoses or famous brain surgeons, because I get invited to those things," Ek says evenly. "And on top of that I get to hang out with artists I've admired since I was a kid. That's pretty fun."

Spotify's head office occupies the top four floors of a building in an upmarket district of Stockholm and has the typical accoutrements of a hip young tech company. There are graffitied murals, whiteboards covered in Post-it notes, fridges stocked with complimentary soft drinks and a staircase lined with informal employee snapshots. Meeting rooms are named after songs: Paranoid, Poker Face, Pretty Vacant. There are areas dedicated to pool, darts and table tennis. Ek still smarts at the memory of his 21-1 table-tennis defeat by a visiting Justin Bieber. "I'm the worst loser ever so I don't even try unless I know I can win," he says.

Spotify also has distinctly Swedish features, such as an unusually flat, democratic management structure and an attitude best described as lagom. "Lagom means not too little but not too much – just enough," explains Ian Robbins, Spotify's US-born product owner of artist products. "It comes up a lot. Our former font was called Lagom. It's very Swedish and it's pervasive."

There is, however, a more practical reason why Spotify was a revolution that could only have happened in Sweden, and the seeds were sown 15 years ago.

In the late 1990s, the Swedish government decided to build a society of digital natives. It treated high-speed broadband as an essential public utility and funded schemes to enable every citizen to buy a computer. Unfortunately for the music industry, this digital evangelism coincided with the launch of the American file-sharing site Napster. Young Swedes could now access any music they liked, for free, faster than anyone else, and they did so with gusto. Sundin, a shaven-headed man with a blunt, sardonic manner, tells me that he began to worry when neighbours mentioned that their teenagers had told them not to bother buying music anymore.

With the arrival of Sweden's own Pirate Bay in 2003, piracy became endemic and the industry contracted at sickening speed. In 1999 worldwide revenue reached an all-time high of $27bn; by 2008 it had almost halved, despite the industry's various legal and technological attempts to fight back. Sweden had the worst piracy in the western world. Sundin estimates that at Universal and, before that, Sony BMG, he personally laid off 200 staff. In 2006, during a Swedish election debate, both leading candidates for prime minister said that they wouldn't criminalise a generation for downloading music, effectively endorsing piracy.

After the debate, Sundin's mother phoned to advise him to find another job. "It was already going down and then they said that," he remembers with a grimace. "It was terrible. All the newspapers were laughing at us." So when Ek came knocking, Sweden was the ideal petri dish for a radical experiment.

Sundin compares the industry to an alcoholic who has to reach rock bottom before he admits he has a drinking problem. He was so impressed by Spotify's demo version that he convinced his bosses to back it: together with other large labels and the Merlin consortium of key independents, Universal owns around 20% equity in Spotify. "I said to my team, 'This is Jesus coming to town! If this fucks up we're going to be dead so let's go all in.'"

"The music industry was in the shitter," says Ek. "What did they have to lose? On top of that, I literally slept outside their offices, coming in week after week, hammering them down argument by argument."

Spotify went live (by invitation only) in Scandinavia, the UK, France and Spain in October 2008. A few months later, Swedish prosecutors backed by the international music industry successfully took Pirate Bay to court, and the government finally introduced EU anti-piracy measures. "It was the perfect storm," says Sundin. "It wasn't just that it was now illegal. People discovered Spotify and realised it was actually better than piracy."

To Ek, the music industry's nosedive was a problem to be solved. "There was this paradox," he says. "People were listening to more music than ever in history and yet the music industry was doing worse and worse. So the demand for content was there but it was a different business model."

Ek's theory was that people were willing to do the right thing but only if it was just as rewarding, and much less hassle, than doing the wrong thing. He says that Spotify subscribers don't pay for content – they can get that for free through piracy – they pay for convenience.

Owen Smith, 27, a Brit who works on Spotify's platform strategy, understands that transition first-hand. At university he filled a hard drive with pirated mp3s. "I'm of the Napster generation," he says, a little bashfully. "It was all there and everyone was doing it and it was almost too good to be true."

After signing up to Spotify in 2008, his behaviour changed. "I didn't think, 'This is the morally better choice'. It was just easier. Over time the hard drive became disconnected. It's funny when it has happened to you and you didn't even realise it."

Sundin has the bullish optimism of someone who has survived a near-death experience. In Sweden, total industry revenues are now approaching 2003 levels; Universal is almost back to its 1999 peak; piracy has plummeted.

"Sweden has gone from bad boy to poster boy in five years," he says with a triumphant grin. "Everyone is looking at what happens in Sweden."

Daniel Ek has straddled the worlds of music and tech since his childhood in Stockholm's down-at-heel Rågsved district. His maternal grandparents were both musicians and he writes and plays music himself: a mint-green electric guitar hangs on his office wall. He is also a computer prodigy who was earning several thousand pounds a month from designing and hosting websites while he was still at school.

After dropping out of an engineering course at the prestigious Royal Institute of Technology, he became a hotshot programmer for internet marketing company Tradedoubler, treating himself to a red Ferrari and a club-hopping lifestyle, but he was unfulfilled and depressed.

He sold the car, swapped his city-centre flat for a cabin near his parents, concentrated on music and meditation, and began hanging out with his former Tradedoubler employer Martin Lorentzon, who was equally disillusioned. In 2005, the two decided to collaborate on a new project that they genuinely cared about.

The company name originated during a last-minute brainstorming session when Lorentzon misheard one of Ek's suggestions (Ek forgets what) and registered the domain name Spotify, now retroactively explained as a portmanteau of "spot" and "identify".

When Ek wasn't overseeing a handful of engineers in a converted three-room flat above a coffee shop, he was out trying to secure global licences from record labels.

After a wave of rejections he narrowed his focus to Europe, which still took a nerve-racking two years with no income. "When we said we wanted to give it away for free and that would help the industry there was a credibility gap that took two years to overcome," admits Jonathan Forster, Spotify's European general manager and one of Ek's first dozen employees.

Minds only began to change when Ek loaded a demo with pirated tracks so that label executives could try it for themselves. Söderström, 37, compares Spotify to Skype: it wasn't a brand new idea but it was faster, easier and more social than the rest.

The basic user experience remains unchanged. You can search for any song in the catalogue, on an interface similar to the iTunes store, and play it as quickly as if it were on your own desktop. Ek was obsessed with shaving milliseconds off the response time. The human brain perceives "instant" as anything less than 250 milliseconds; Spotify plays songs within 285. Songs can then be shared via playlists, over 1billion of which have been created so far.

You either listen for free, if you don't mind intrusive adverts and a 10-hour monthly cap, or pay $4.99 a month ("unlimited") for uninterrupted listening, or $9.99 ("premium") to listen on a mobile device. The 2009 introduction of the mobile service, including an offline feature, was the turning point in terms of incentivising users to pay. Between 20-25% of Spotify users (currently six million people) upgrade to a subscription. "A lot of people said it was really stupid to start charging when everyone else was free, and we weren't as sure about it as we like to say we were," says Söderström. "It was a big risk."

Spotify's product development motto is spelt out in colourful plastic letters on a wall near Ek's office: "Think it, build it, ship it, tweak it." Usually, its instincts are correct. Rather than clogging the site with secondary services, for example, it has made the app available to third parties such as the gig-listing service Songkick and journalism sources including Guardian Music. Its current focus is on "discover", which introduces listeners to music via Spotify Radio, curated playlists and algorithmic recommendations.

Its only significant blunder to date occurred during its alliance with Facebook in September 2011, when it prioritised sharing over privacy. Suddenly existing users found that all their listening was public while new ones couldn't sign up without a Facebook account. After a fierce backlash, both obligations were dropped. "We look back on that as a 'duh' moment," says Robbins. "How did we not understand that?" He shrugs. "We learn by doing."

Despite Spotify's lagom demeanour, its ultimate goal is far from moderate. "I want everyone in the world to be able to listen to anything ever created," says Söderström. "And I think we'll get there."

For that to happen, many artists remain to be convinced. Although former refuseniks Pink Floyd recently came on board, the representatives of acts ranging from the Beatles to Boards of Canada are currently holding back most or all of their catalogue. Some, like the Black Keys and Thom Yorke's new band Atoms for Peace have been publicly hostile. "New artists get paid fuck all with this model. It's an equation that just doesn't work," Yorke's bandmate Nigel Godrich recently tweeted.

"The concern is genuine and understandable," says the unflappable Söderström. "If you put your entire life into creating art, of course you're going to be careful about it. Fortunately we now have tangible data. We try to inform and be as transparent as possible."

The key issue is royalty payments. Spotify says that around 70% of its income subscriptions is paid into an industry pool, from which individual copyright holders pay their artists, albeit not very transparently. Artists' income will only grow as the user base expands. Spotify finally launched in the US in 2011 and eventually aims to cover the entire world. By last February, it had paid out $500m to rights holders to date; by the end of 2013 that figure will have doubled. Of course, that $1bn pie is divided into an awful lot of slices.

Mark Williamson, director of Artist Services, says that payments are not calculated on a per-stream basis but insists, "The rates are equitable across labels." Working back from their royalty statements, several artists have calculated the rate at around 0.4p per stream, so you need over 200 plays to match the 99p paid for one iTunes download. Whether or not that is fair depends on what you're comparing it to. If you count every stream as a lost sale then it's disastrous. If, however, you compare it to YouTube (whose rates are secret but reportedly lower) or piracy then it's not so bad.

"This is not a dollar business anymore; it's a nickel-and-dime business," insists Sundin. "If you don't get played then you're not popular and you don't get money. Accept it. Kids like what they like."

He pulls up a graph on his laptop to show me that one of his artists, the Swedish electronic dance-music producer Avicii, had 3.7 million plays the previous day while U2 receive about 250,000 every day. Traditionally, the average album earned most of its revenue within a couple of months and then dipped as interest waned and retail shelf-space was ceded. On Spotify, theoretically, a song never need stop earning money.

The Scandinavian experience suggests that Spotify is good for the industry's overall revenues because it benefits heavyweight stars, back catalogue and viral hits. Stephan Markovits, who works in the Swedish electronic dance-music scene, points out that Million Voices, a 2012 single by local DJ Otto Knows, has been streamed more than 28 million times. "People create playlists, they have house parties, they go to work on the bus, so a song will live for longer rather than going up and down quickly," he says.

However, high-profile sceptics such as the musician David Byrne have argued, it will not help every kind of artist. Consider a cult band who don't have hits but currently sell enough CDs to survive. If every single one of their fans switched from ownership to streaming, the band would need at least 200 times as many new listeners to make up for the shortfall. The numbers game doesn't work for them.

The sceptics see Spotify as inimical to new and independent musicians. "We don't support Spotify at all," says Lohan Presencer, chief executive of Ministry of Sound, whose roster includes Wretch 32, Example and London Grammar. "From a business perspective it doesn't make sense for us and our artists." He believes that as well as paying poor royalties, Spotify cannibalises sales, offers less promotional benefit than YouTube, and "propagates a myth that music is free". And he is dubious about Spotify's expansion plans because it still makes a net loss: €58.7m in 2012 despite revenues of €434.7m.

"How sustainable is that business model? Is it going to get 100 million users or is it going to run out of money before that point? Should we, as an industry, be supporting a business that has no real prospect of succeeding? The justification that it is saving the industry from piracy is a bit rich. Their objective is to build a business and then to sell it before they run out of cash."

Söderström counters that Spotify "could have been profitable several times" but has chosen to invest everything in new staff (currently more than 1,000 worldwide), products and territories. He also says that Ek, while enormously wealthy on paper, has not cashed in by selling Spotify. "Why hasn't he? Because he actually cares about music. He wants to solve that problem. He would like to see a world where you can listen to music without ripping people off."

Forster adds: "No matter how many times I say that Daniel's not interested in the money nobody's ever going to believe me. But frankly that's not what motivates him. He likes to build things. If you think about a product that gives you the potential to touch literally everyone in the world, it's boy's own stuff. There's no issue with Daniel thinking big."

Apparently not. Spotify was born out of a single correct assumption about human behaviour, namely that music fans would embrace, and even pay for, a legal service if it was virtually frictionless. Now the company's colossal volume of granular data makes assumptions unnecessary.

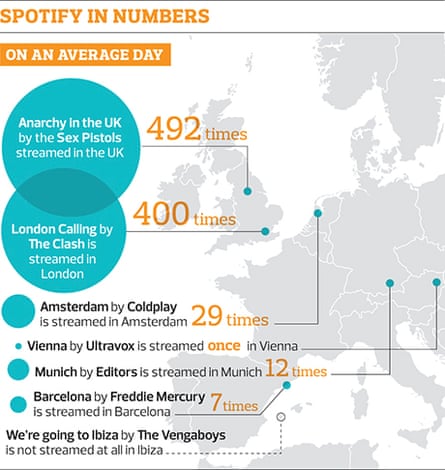

Before digital music, the industry's understanding of consumer behaviour ended at the point of sale, but Spotify knows who listens to what, and when and where they do so. Artists can tweak their tour schedules based on regional data or choose singles based on which album tracks are most popular. Spotify already changes how music is heard. It may soon change how it is made.

"I think we're in the middle of a transition but it hasn't moved all the way," says Ek. "Why are we releasing albums the same way as we did 10 years ago? Music is no longer restricted by the format it's on.

"We make audio records alone when they could be audio-visual-interactive. That's what I find interesting: What's the future of the album? That's something we've only begun to touch."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion