The inexorable rise of constructed reality television was boosted last week when ITV2's The Only Way is Essex took home Bafta's YouTube Audience Award, beating the likes of Downton Abbey, Miranda and Sherlock to the prize. As the canny director at the ceremony cut to a close-up of Martin Freeman, the actor's expression spoke volumes about the television establishment's reaction to a bunch of spray-tanned amateurs waltzing off with a trophy more usually afforded to skilled craftspeople. He wasn't angry with the voting public, just disappointed.

In an age when TV fakery scandals have caused public uproar, why is a huge audience buying into something so obviously artificial? Most television involves a level of artifice. Everything from The Apprentice to Top Gear uses sleight of hand to better convey the story of each episode. But this new hybrid genre – of which E4's Made in Chelsea is another example – is neither fiction nor reality but a strange marriage of the two. Are we supposed to believe it?

The Only Way is Essex arrived soon after the end of Channel 4's Big Brother last year and is a crossbreed of soap and documentary. It features a cast of real people, living around Brentwood, Buckhurst Hill and Chigwell, going about their daily lives. They are brash, fake-tanned and young. And, most importantly, they conform to the stereotypes of Essex man and woman. He is flash, arrogant and sexually prolific. She is obsessed with beauty treatments and snaring the aforementioned Jack-the-lad.

Programme makers Lime Pictures advertised in various Essex publications, on Facebook and via word-of-mouth to assemble their key players. Mark Wright and Lauren Goodger have been together for nine years and spent most of the first series splitting up and reuniting. Amy Childs, beautician and glamour girl, and a group of friends had already made attempts to break into television, auditioning for Big Brother, The X Factor and various other reality shows.

"They had a pre-existing relationship and they wanted [to do] something like this. So when we met one of them – it was Amy first, actually – all of the others were queuing up behind. This was not a particularly difficult group of people to find," says Tony Wood, creative director of Lime Pictures.

What you see on screen looks like drama but it is, the producers claim, based on the real lives of their subjects. "Story producers" plot out what they are going to film in advance after discussion with the cast – they prime their subjects to discuss certain topics, with an outcome in mind, although they cannot always predict that outcome.

Daran Little, who acted as story producer on the first series of The Only Way is Essex and E4's Made in Chelsea, which is about rich young adults in west London, says it's a delicate process that requires careful handling. "If there's a boy and a girl in a scene, you'll pull them over individually and you'll say: 'Right, in this scene I want you to ask her what she did last night.' Because I know what she did last night, but he doesn't. Then we start the scene and they just talk it through and if it gets a bit dry, we'll stop and pull them to one side and we'll say: 'How do you feel about him asking you that? Because I think you feel more emotional about it. I think you're pulling something back. Do you think it's fair that he's asking you this?'"

The Only Way is Essex was not the first structured reality show to hit British screens but it's certainly had the biggest impact – it has attracted a peak audience of 1.5 million. Interestingly, many of the production team have backgrounds in drama and not factual television. Lime Pictures also makes the long-running teen soap Hollyoaks, and Wood previously spent two years as the show runner on Coronation Street.

Lime began the UK trend for these documentary/drama hybrids back in 2006 when MTV asked it to make a British version of the hit US show Laguna Beach: The Real Orange County, altering it to be about a group of rich teenagers in Alderley Edge, Cheshire. The US show was inspired by teen drama The OC and borrowed many of its techniques to create a kind of real-life soap. "Living on the Edge was essentially a reality show that was repackaged a little bit to make it look glossy and look like drama," says Wood. "There were very few contrivances within it but you had the latitude to be able to put an emotional mix on it, in a sense."

Living on the Edge ran for two series and, although not a ratings hit, set a pattern for programmes that followed. British TV executives couldn't fail to notice the huge US success of programmes such as The Hills and The City (spin-off shows from Laguna Beach); staged documentaries that followed beautiful, wealthy teenagers as they went about their privileged lives. They were aspirational, escapist and focused almost exclusively on the romantic attachments of the cast.

Little, who has previously written for EastEnders, Coronation Street and the US soap All My Children, says that during his time in America, the schedules were overrun with similar reality dramas. "There are so many reality TV shows in the States and if you're going to avoid them, then you might as well avoid television," he says. And now they are springing up all over our digital schedules amid press accusations that scenes are being "faked" and relationships are being "manufactured" to assist the narrative.

Little insists the production process is very much at the mercy of the participants and not the other way around. "I get to know them," he says. "They tell me what's going on in their own lives. They tell me things they want to do, or hope to do. I structure, scene by scene, what should happen in each episode to draw out the drama and the comedy. Then we schedule the scenes."

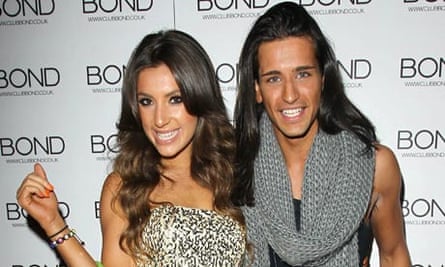

A drama is only as good as its actors and, at first glance, these shows appear to be almost entirely peopled by artless hams – yet they're hugely popular with their target audiences. When Little interviewed Made in Chelsea cast members Ollie Locke and Gabriella Ellis, he instantly spotted their potential. "They had been together for a year. I talked to them together and their body language was completely different to what they were saying. And I thought, this is a relationship which is crumbling and she's not too aware of it. And he's hurting her. Oh my goodness, this will actually make very good television."

And, sure enough, in episode three, Ollie dumped Gabriella on the deck of a Thames pleasure cruiser, surrounded by fairy lights. Little says Ollie had called the production team and told them he needed to end the relationship so they swung into action to set up a suitable shot. While Ollie gave it his all in the scene, Gabriella looked genuinely upset. The next episode, he came out as bisexual. Faked content is one thing, but the idea that it's all real is perhaps even more disturbing.

The shows have the glossy production values of a soap but are performed by people who don't have the skill to convincingly communicate emotion in full makeup, under bright lights, while hitting their marks. Wood says filming scenes more than once isn't always an option with real people. "We very, very rarely go to multiple takes. I spend a lot of time in the edit and if in the cutting room you're presented with a take where they're clearly manufacturing their emotions, it's tough to make a decent scene out of that."

But it's clear that this is often the only option. It's the lack of emotional truth that has so confused and repelled some viewers. Wood claims that the confusion is exactly what the makers were aiming for when they made their chronicle of the Essex community.

"At the heart of this was always a desire to put in the audience's mind: 'Is it real? Are they acting? Is it scripted? Is it not?' and to leave that as an open question for them," he says.

What he describes almost sounds like Brecht's Verfremdungseffekt or "alienation effect". (Brecht described this as "stripping an event of its self-evident, familiar, obvious quality and creating a sense of astonishment and curiosity about [it]".) Wood laughs off the comparison but agrees their techniques aren't dissimilar. The usual soap tricks – music, editing, a narrative arc – encourage the viewer to engage, while they are simultaneously held at arm's length by the cast's apparent lack of emotional integrity.

But to what end? To generate debate on social networking sites, drive curious viewers to the TV product and keep the advertisers happy? It's as if what's actually in the shows has ceased to matter.

"The content seems to be a Marmite issue for people: you love it or you hate it," says Fergus O'Brien, the documentary-maker responsible for BBC2's The Armstrongs, a fly-on-the-wall documentary that itself had audiences questioning whether the hilarious titular couple could really be the genuine article. (They were.) "Some people think it's deceiving people to suggest there is anything real about it; others say it's harmless fun," he says.

O'Brien directed Channel 4's Seven Days earlier this year. The series chronicled the lives of residents of London's Notting Hill over a week and, although it didn't use staged scenes, gave the audience a chance to interact with the cast during filming. It proved less successful than The Only Way is Essex in terms of ratings, but it attempted to do something new with the documentary form at a time when every production company in the land was trying to predict what would come along to fill the yawning chasm left by Big Brother.

"It covered the real events and interactions of the characters over a seven-day period and embraced the feedback loop that naturally generated around the characters as the week went by," O'Brien explains. The participants would see their stories play out on the screen while filming continued thanks to a fast turn-around production schedule. Whereas Made in Chelsea was already finished when it started transmission, the Essex cast are able to see themselves on television as each episode is shot, edited and broadcast within a three-day period.

Wood traces his fascination with the genre back to the moment when, in 2007, Jade Goody emerged from the Celebrity Big Brother house and into the media hurricane of the Shilpa Shetty race row. It was that moment of simultaneous celebrity and sudden self-knowledge that he hoped to expand on in The Only Way is Essex.

"What I wanted to do was set up a situation in which people are living in the full glare of the beam of that fame. And they're realising what the public are saying about them and it's completely open and they're potentially on quite a difficult ride as a result of that," he says.

"We deliberately showed, at the top of episode two, the cast watching the episode that had just gone out. So we gave the message that this is what the game is," he adds. When Lime pitched the show to ITV originally, it described it as "Big Brother without the walls".

But during a decade of Big Brother, despite the presence of storyline producers and careful editing, the reality created inside a bungalow in Borehamwood felt somehow more honest than the shaped and refined sagas currently coming out of Essex and Chelsea, which have hints of real emotion but nothing to touch the visceral highs and lows of Big Brother at its best. These new shows remain in the digital hinterland for now but are having a significant impact thanks to Twitter and the tabloids' interest in the cast. As the Bafta-night reaction highlighted, The Only Way is Essex has replaced Big Brother as the programme people sneer about at dinner parties without having seen it. But is it any worse, in terms of artifice, than character-driven factual shows such as The Apprentice or MasterChef?

Little says hindsight will invest this apparently superficial genre with cultural importance, just as it did with the Carry On films. "Retrospectively, these wonderful programmes are being made about what a genius Kenneth Williams was and how tortured Hattie Jacques was and the great art of the Carry On film. Well, give it 10, 15 years and people will be writing theses on The Only Way is Essex."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion