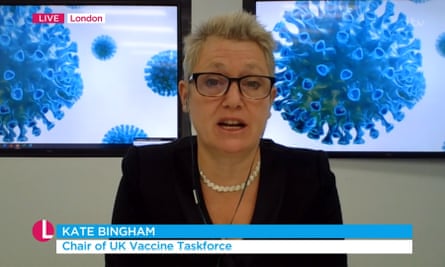

The great global hope raised this week by news of successful trials for a Covid-19 vaccine interrupted a very British row about the head of the UK’s own vaccine efforts, who was appointed in May and reports directly to Boris Johnson.

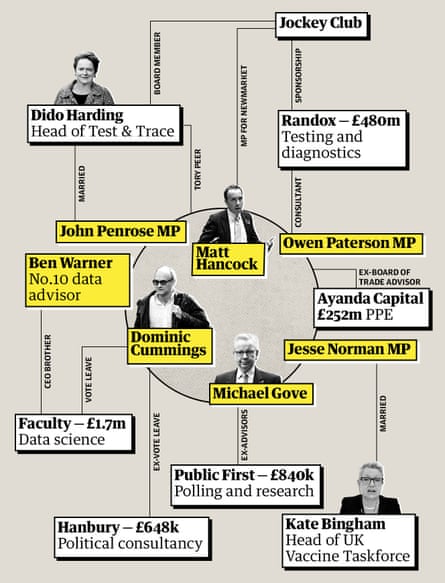

As Kate Bingham, chair of the vaccine taskforce, came under sustained scrutiny over a £670,000 spend for public relations consultants, attention switched from her suitability for the role to her connections to the Conservative government.

Managing partner of a private equity firm, SV Health Investors, involved for 30 years in pharmaceutical investment, she is also married to a Tory MP, Jesse Norman, who was at Eton at the same time as Johnson, and she went to private school with Rachel Johnson, the prime minister’s sister.

The pandemic’s devastating hold over British life has shone an unsparing light on the country’s defining features: the divide between north and south, the wealthy and less well-off, the vulnerability of black and minority ethnic communities.

The anti-establishment claims of a government led by Johnson and Dominic Cummings were always audacious, and in the appointments and contracts awarded during the pandemic, the shape of a Tory establishment has come into focus. Critics are calling it a “chumocracy”.

Companies benefiting from government contracts awarded during the pandemic have links, among others, to the Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove and Cummings, the prime minister’s chief adviser. Cummings shock departure from Downing Street following the resignation of his close ally Lee Cain, who was head of communications, now signal a realignment of power in No 10, but the web of connections drawing complaints of “cronyism” extend beyond any single Tory faction.

Bingham’s appointment shares similarities with that of Dido Harding, to head the NHS test and trace operation in May. She was made chair of NHS Improvement in 2017 after an open recruitment process, her CV gleams with executive experience, and also opens a window to a small world of Conservative connectedness. Married to the Tory MP John Penrose, she was given a peerage in 2014 by David Cameron, a friend, and sits in the House of Lords as a Conservative.

Neither Bingham nor Harding are being paid for their roles, but critics complain that two central pillars of the pandemic response, vaccines and testing, are being led by two well-connected executives appointed without an evident formal process.

A racehorse owner and keen rider, Harding was in 2004 appointed as a member of the Jockey Club, which gave the local Newmarket MP and current health secretary, Matt Hancock, another horseracing enthusiast, honorary membership of its prestigious rooms, shortly after he was first elected, in 2010.

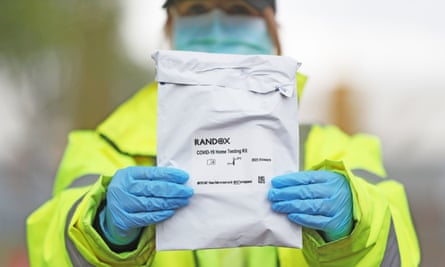

The racing and Tory connections extend to Randox Laboratories, the Northern Irish healthcare company that was given a £133m contract in May by Hancock’s department to produce testing kits, recently extended by six months for a further £347m. Owen Paterson, Conservative MP for North Shropshire since 1997, is paid £8,333 per month for 16 hours work as a consultant for Randox. The company is the official healthcare partner of the Jockey Club, and has sponsored the Grand National since 2016.

Both the initial Randox deal for tests, and its recent extension, were awarded under the emergency Covid-19 regulations that waive standard rules requiring competitive tenders for public contracts, enabling Johnson’s government to directly hire chosen firms at speed. Neither Randox nor Paterson responded to requests for comment.

In the latest twist to the controversy over appointments, the Sunday Times reported that George Pascoe–Watson, UK chairman of lobbying firm Portland Communications, was made an unpaid adviser to a health minister during the first wave of the pandemic without any public process or announcement. Pascoe–Watson told the newspaper that information he and Portland passed to private clients in October about the government’s stance on future lockdowns was “in no way connected” to calls he had access to in his advisory work for the government.

Contracts

Amid the billions spent, some multimillion-pound contracts for the supply of personal protective equipment have been criticised by campaigners, including the not-for-profit Good Law Project (GLP), which has highlighted several Tory links.

While the emergency regulations could be expected to enable urgent commissioning of tests, PPE and other medical supplies, the government’s contracting of data, policy and communications companies has perhaps come as more of a surprise.

Four of the companies engaged for such consultancy services on contracts not put out to tender have political links either to the government, Conservative party, Cummings himself or the Vote Leave campaign he ran during the Brexit referendum.

In June the Cabinet Office, whose minister is Michael Gove, published details of a contract that had been running under the emergency regulations since March with the policy consultancy Public First, to research public opinion about the government’s Covid-19 communications. The company is owned by the husband-and-wife team James Frayne, previously a long-term political associate of Cummings, and Rachel Wolf, a former adviser to Gove who co-wrote the Conservative party manifesto for last year’s election.

Frayne and Cummings first worked together approximately 20 years ago on Business for Sterling, the Eurosceptic campaign against Britain joining the euro, and then in 2004 at the rightwing thinktank, the New Frontiers Foundation.

After Gove became education secretary following the 2010 election – with Cummings as his chief adviser – Frayne was from 2011-12 the Department for Education’s (DfE) director of communications, a civil service appointment. Frayne told the Guardian that after leaving the DfE in 2013 he worked in commercial consulting, setting up Public First in 2016. He said he has not been personally in contact with Cummings or Gove for some years.

Despite his wife’s recent work on the Tory manifesto, he insisted their company was engaged by the Cabinet Office because it is known for high-quality focus group and policy work, not because of its connections. The upper limit for the Cabinet Office contract was £840,000, but Frayne said they had billed about £550,000 in total, and that the work had a “low margin” of profit.

Public First was also contracted to advise the exams regulator Ofqual on its communications before and after the summer debacle over the awarding of A-level and GCSE grades, and had a £116,000 contract with the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) to advise on joining up health and social care. The value of these contracts was below the level at which a competitive tender is required.

Another very well-connected company that has profited from directly awarded contracts during the pandemic is Hanbury Strategy. A policy and lobbying consultancy, Hanbury has been paid £648,000 under two contracts, one under the emergency regulations to research “public attitudes and behaviours” in relation to the pandemic, the other, at a level that did not require a tender, to conduct weekly polling.

The company was co-founded by Paul Stephenson, who was director of communications for the Vote Leave campaign, working with Cummings. Stephenson is now among the names tipped as potential new chief of staff for the prime minister. In March last year, Hanbury was given responsibility for assessing job applications for Conservative party special advisers.

Tory–linked appointments and firms

When its government contracts were first reported, Hanbury said its “leading experts” had worked with different political parties and governments internationally, and it was proud of its work for the British government during the Covid-19 crisis.

On 17 March, six days before Johnson finally imposed the first lockdown, the Cabinet Office gave the political communications company Topham Guerin a £3m contract under the new emergency regulations. Run by two New Zealanders, Sean Topham and Ben Guerin, the company had produced social media content for a number of rightwing political parties, including the Conservative party’s 2019 election campaign.

It was Topham Guerin that was behind two notorious Tory stunts during the election: renaming the official Conservative party Twitter account “factcheckUK” during the leaders’ debate, and setting up a website presented as Labour’s manifesto.

The £3m Covid-19 work was to sharpen the government’s messaging, and Topham Guerin is reported to have suggested on a call with Stephenson and Lee Cain, that the “stay home, save lives” slogan had worked in some other countries. The government adopted that with “protect the NHS”, reportedly suggested by Cain.

Topham Guerin’s £3m contract concluded in September; the Cabinet Office says it has exercised the option to extend the company’s work for a further six months.

Meanwhile, the artificial intelligence and data analytics company Faculty Science Ltd, which worked with Cummings for Vote Leave in the referendum, has been awarded a string of government contracts since 2018. After Johnson became prime minister, a former Faculty employee who worked on Vote Leave, Ben Warner, was recruited by Cummings to work alongside him in Downing Street.

Warner, who is the brother of Faculty’s chief executive, Marc Warner, is reported to have run the data modelling for the Conservative party’s general election campaign in 2019. A close Cummings ally, he regularly attends the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage) on behalf of No 10, although he is one of several aides who reportedly may now exit amid a changing of the guard at Downing Street.

Under the emergency pandemic regulations, Faculty has been engaged on a £400,000 contract with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, and two contracts totalling approximately £350,000 with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

That government work was in addition to a £930,000 contract with the DHSC to be the AI lab partner for NHSX, the digital arm of the NHS, which began on 2 February and was awarded following a competitive tender. That contract was extended to include work on the Covid-19 datastore, an “unprecedented” data project also involving Palantir, a US firm founded by the libertarian billionaire Peter Thiel.

A Faculty spokesperson told the Guardian that the work for Vote Leave in 2016 was to provide polling analysis and advice on reducing advertising costs. “This was a commercial contract,” she said. “Faculty would equally have worked with Remain, had they asked.” The spokesperson stressed Faculty’s expertise, and said all of its government work was “won through a fit and proper process”.

Connections

The Good Law Project has challenged some government contract awards to companies with Tory connections, and is increasingly focused on those for PPE. The case of Ayanda Capital, an investment firm that won a £252m contract in April to supply face masks, was raised with Johnson by the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, in parliament this week. Ayanda’s chief executive, the financier Tim Horlick, has strongly denied allegations that millions of its masks were unusable, saying the issue was the Cabinet Office requesting the final consignments to be headband style rather than with ear loops. The government appeared to support that view in its response to the GLP, saying “a wider issue” emerged as to whether ear-loops provide “an adequate fixing”.

The GLP drew attention to the involvement for Ayanda at the bidding stage of Andrew Mills, at the time an adviser to the Board of Trade, an arm of the Department for International Trade (DIT), where Liz Truss is the minister. Horlick has said that Mills was “told to go to the public portal” for procurement “like everybody else”, and the DIT said neither it nor the Board of Trade was involved in the Ayanda deal. Mills has since been replaced on the Board of Trade when it was “refreshed” in September.

The prime minister has repeatedly rejected accusations of “cronyism” made by the Labour opposition in the award of contracts, and in an exchange with Starmer at the dispatch box he hailed the contributions made by commercial companies in the pandemic. The government maintains that both Harding and Bingham are very well qualified and have made great successes of their roles.

However, Liz David-Barrett of the University of Sussex, an adviser to the Cabinet Office on the UK’s anti-corruption strategy, argues there are “red flags” when the competitive tendering process for government contracts is suspended and contracts are awarded to companies with connections.

“Competition and transparency for government contracts are hard-won processes, very important if the public are to have confidence that the best people are providing public services,” she said. “If the processes are suspended for a long time, there is a risk that it becomes the norm, and confidence is undermined.”

On Thursday the government in effect agreed; Julia Lopez, a Cabinet Office minister, said an internal review would be held into the awarding of private contracts during the pandemic, so ministers could be sure there was “no basis” for claims of favouritism to Tory supporters or donors. The National Audit Office is also carrying out its own review into procurement.

Throughout, as concerns have grown about the networks of Tory-linked relationships highlighted by the business done during the pandemic, it might be of some reassurance that the UK has an official anti-corruption champion. Perhaps less reassuring is that the champion is John Penrose, Conservative MP and husband of Dido Harding.

The Scott Trust, the ultimate owner of the Guardian, is the sole investor in GMG Ventures, which is a minority shareholder in Faculty.

Additional reporting by Joseph Smith