Abstract

Objectives

This paper tests the economic theory of criminal behavior. Specifically, it looks at “the carrot” side of the theory, studying how thieves react to changes in monetary gains from crime.

Methods

Using a unique crime-level dataset on metal theft in the Czech Republic, we study thieves’ behavior in a simple regression framework. We argue that variation in metal prices represents a quasi-experimental variation in gains from crime. It is because (1) people steal copper and other nonferrous metals only to sell them to scrapyard and (2) prices at scrapyards are set by the world market. This facilitates causal interpretation of our regression estimates.

Results

We find that a 1% increase (decrease) in the re-sale price causes metal thefts to increase (decrease) by 1–1.5%. We show that the relationship between prices and thefts is very robust. Moreover, we find that thieves’ responses to price shocks are rapid and consistent.

Conclusion

Our results are in line with the economic model of crime, wherein criminal behavior is modeled as a rational agent’s decision driven by the costs and benefits of undertaking criminal activities. Our estimates are also consistent with recent results from the United Kingdom, suggesting these patterns are more general.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

-

See “A Guide to the LME,” London Metal Exchange, PDF file, 2014, at http://www.lme.com/~/media/Files/Brochures/A Guide to the LME, last accessed on June 28, 2016. See also Watkins and McAleer (2004).

-

For more extensive and insightful discussion of the price-theft hypothesis in the realm of non-ferrous metal markets see also Sidebottom et al. (2011).

-

See “Thieves Steal Local Bridge,” CBS Pittsburgh, Online, October 7, 2011, at http://pittsburgh.cbslocal.com/2011/10/07/thieves-steal- bridge-in-lawrence-county (last accessed on June 28, 2016); “Czech metal thieves dismantle 10-ton bridge,” The Telegraph, Online, April 30, 2012, at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/9235705/Czech-metal-thieves-dismantle-10-ton-bridge.html (last accessed on June 28, 2016); and “Thieves Steal Entire Bridge in Western Turkey,” Time, Online, March 21, 2013, at http://newsfeed.time.com/2013/03/21/thieves-steal-entire-bridge-in-western-turkey (last accessed on June 28, 2016).

-

See “Copper Thefts Threaten U.S. Critical Infrastructure,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, Criminal Intelligence Section, Online, September 15, 2008, at http://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/copper-thefts (last accessed on June 28, 2016) and resources therein. For policy papers on costs of metal thefts, further background, and potential measures see Bennett (2008, 2012b, 2012a); Kooi (2010); and Lipscombe and Bennett (2012).

-

“Evidenčně? statistický systém kriminality” in Czech.

-

The reason why the other yards could not provide us with the data, which their personnel gave most often, was simply that the prices change very frequently and they do not keep records. However, the personnel often stated that their prices are determined by the market.

-

The amendment was published on December 22, 2008 as Directive no. 478/2008.

-

Although metal theft has been a continuous public concern and proposals for an intervention were discussed frequently in media and politics, it was only in March 2015 that scrapyards were prohibited from buying scrap metals and other items for cash. A referee noted that scrapyards became obliged to identify sellers and keep a record of individual transactions. However this obligation was already present the Directive 383/2001, which is the general directive that regulates the operation of establishments dealing with waste, that was effective from January 1, 2002 (a year before our the first year of our data). In particular, scrapyards were required to keep a record of the kind and amount of the items bought as well as the name, address, and the serial number of the Identity Document of the seller. This obligation applied to a list of items that contained all nonferrous metals as well as their mixtures and cables.

-

See Murray (1994) for an excellent non-technical introduction into nonstationary processes and cointegration.

-

See Davidson and MacKinnon (2003, ch. 14.6) for an overview and discussion of testing for cointegration.

-

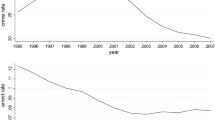

The two series are plotted in Fig. 5 in the Appendix. We note that it is not clear whether property crime should be controlled for or not. It is possible that offenders may substitute metal thefts and other property, depending on their relative valuation. In that case, property crimes would be affected by copper prices, and regressions controlling for property crimes would underestimate the effect of prices on metal thefts. Note, however, that the average number of property crimes per month in our data is 18,400 while the average number of metal thefts is 280, so the bulk of variation in property crime will probably be unrelated to substitution from metal thefts (see Table 3). More importantly, one might argue that not including property crimes would lead to overestimating the effect of prices on thefts, as new metal thefts may represent substitutes for other opportunities and not new crimes. We lean towards the latter approach and prefer the regressions controlling for property crimes and bicycle theft in order to net out these potential substitution effects and control for general crime trends. We further delve the issue of substitution in Sect. 4.4.

-

Note that \(\hat{\epsilon _t}\) is an estimate of \(\epsilon _t\) containing measurement error. Therefore, our estimates of \(\gamma _1\) will be biased towards zero. We are grateful to Giovanni Mastrobuoni for pointing this out to us.

-

Note that using the 10% level, the Augmented Dickey–Fuller tests fail to reject nonstationarity of residuals from specifications (1), (7) and (8), so these results should be interpreted with caution.

-

See “2012 trading volumes,” Online, at https://www.lme.com/metals/reports/monthly-volumes/annual/2012/ (last accessed on July 7, 2016).

-

We are grateful to Nikolas Mittag for raising some of these points.

-

For discussion of market forces and dynamic aspects of illicit trade see also d’Este (2014). Looking at the effects of pawnshop availability on property crime in the US, he finds an elasticity of property thefts to pawnshops of between 0.8 and 1.5.

-

In a review of 102 studies, Guerette and Bowers (2009) find no systematic evidence of displacement of criminal activity following an intervention. About one fourth of studies find some displacement, yet it is never complete. However, about the same number of studies found diffusion of benefits.

-

We are grateful to David de Meza for pointing this out to us and suggesting a more direct test we report below. See also the discussion in footnote 13.

-

See “In Russia, Stealing Is a Normal Part of Life,” Los Angeles Times, Online, September 21, 1998, at http://articles.latimes.com/1998/sep/21/news/mn-25012 (last accessed on June 28, 2016).

References

Aaltonen M, Macdonald JM, Martikainen P, Kivivuori J (2013) Examining the generality of the unemployment-crime association. Criminology 51(3):561–594

Aebi MF, Linde A (2010) Is there a crime drop in Western Europe? Eur J Crim Pol Res 16(4):251–277

Aebi MF, Linde A (2012) Conviction statistics as an indicator of crime trends in Europe from 1990 to 2006. Eur J Crim Pol Res 18(1):103–144

Aruga K, Managi S (2011) Price linkages in the copper futures, primary, and scrap markets. Resour Conserv Recycl 56(1):43–47

Ayres I, Donohue JJ III (2003) The latest misfires in support of the “more guns, less crime” hypothesis. Stanf Law Rev 55(4):1371–1398

Beccaria C (1995/1764) On crimes and punishments and other writings. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ 76(2):169–217

Bennett L (2008) Assets under attack: metal theft, the built environment and the dark side of the global recycling market. Environ Law Manag 20:176–183

Bennett O (2012a) Scrap metal dealers bill. Research paper no. 12/39. House of Commons Library, London

Bennett O (2012b). Scrap metal dealers bill: committee stage report. Research paper no. 12/66. House of Commons Library, London

Bentham J (1823) An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation, vol 2. Printed for W. Pickering, London

Bentham J (2008/1830) The rationale of punishment. Prometheus, Amherst

Bottoms A, von Hirsch A (2010) The crime preventive impact of penal sanctions. In: Cane P, Kritzer HM (eds) The Oxford handbook of empirical legal research. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 96–124

Brown K (2008) Regulating bodies: everyday crime and popular resistance in communist Hungary, 1948–1956. Dissertation thesis, University of Texas at Austin

Cameron S (1987) Substitution between offence categories in the supply of property crime: some new evidence. Int J Soc Econ 14(10):48–60

Chisholm J, Choe C (2005) Income variables and the measures of gains from crime. Oxf Econ Pap 57(1):112–119

Clarke RV (1997) Introduction. In: Clarke RV (ed) Situational crime prevention. Harrow and Heston, Guiderland, pp 1–43

Clarke RV (2012) Opportunity makes the thief. Really? And so what? Crime Science 1:3

Clarke RV, Cornish DB (1985) Modeling offenders’ decisions: a framework for research and policy. Crime Justice 6:147–185

Cook PJ (1986) The demand and supply of criminal opportunities. Crim Justice 7:1–27

Cook PJ (2010) Property crime-yes; violence-no. Criminol Public Policy 9(4):693–697

Cook PJ, MacDonald J (2011) Public safety through private action: an economic assessment of bids. Econ J 121(552):445–462

Cook PJ, Zarkin GA (1985) Crime and the business cycle. J Legal Stud 14(1):115–128

Cornish DB, Clarke RV (1987) Understanding crime displacement: an application of rational choice theory. Criminology 25(4):933–948

Cornish DB, Clarke RV (2003) Opportunities, precipitators and criminal decisions: a reply to Wortley’s critique of situational crime prevention. Crime Prev Stud 16:41–96

Cornish DB, Clarke RV (2013) The rational choice perspective. In: Wortley R, Mazerolle L (eds) Environmental criminology and crime analysis. Routledge, London, pp 21–47

Crampton RJ (2002) Eastern Europe in the twentieth century-and after. Routledge, London

Davidson R, MacKinnon JG (2003) Econometric theory and methods. Oxford University Press, New York

Detotto C, Pulina M (2013) Assessing substitution and complementary effects amongst crime typologies. Eur J Crim Pol Res 19(4):309–332

Di Tella R, Schargrodsky E (2004) Do police reduce crime? Estimates using the allocation of police forces after a terrorist attack. Am Econ Rev 94(1):115–133

Draca M, Koutmeridis T, Machin S (2015) The changing returns to crime: do criminals respond to prices? Discussion paper no. 1355, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics

D’Este R (2014) The effect of stolen goods markets on crime: pawnshops, property thefts and the gold rush of the 2000s. Working paper, University of Warwick

Ehrlich I (1973) Participation in illegitimate activities: a theoretical and empirical investigation. J Polit Econ 81(3):521–565

Ehrlich I (1996) Crime, punishment, and the market for offenses. J Econ Perspect 10(1):43–67

Engle RF, Granger CWJ (1987) Co-integration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica 55(2):251–276

Felson M, Clarke RV (1998) Opportunity makes the thief: practical theory for crime prevention. Police research series paper no. 98, Home Office, London

Guerette RT, Bowers KJ (2009) Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefits: a review of situational crime prevention evaluations. Criminology 47(4):1331–1368

Jones MC, Marron JS, Sheather SJ (1996) A brief survey of bandwidth selection for density estimation. J Am Stat Assoc 91(433):401–407

Klick J, Tabarrok A (2005) Using terror alert levels to estimate the effect of police on crime. J Law Econ 48(1):267–279

Kooi BR (2010) Theft of scrap metal. Problem-specific guides series no. 58, US Department of Justice, Washington, DC

Koskela E, Viren M (1997) An occupational choice model of crime switching. Appl Econ 29(5):655–660

Labys WC, Rees HJB, Elliott CM (1971) Copper price behaviour and the london metal exchange. Appl Econ 3(2):99–113

Levitt SD (1998) Juvenile crime and punishment. J Polit Econ 106(6):1156–1185

Levitt SD (1997) Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime. Am Econ Rev 87(3):270–290

Levitt SD (2002) Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effects of police on crime: reply. Am Econ Rev 92(4):1244–1250

Lin M-J (2008) Does unemployment increase crime? Evidence from U.S. data 1974–2000. J Hum Resour 43(2):413–436

Lipscombe S, Bennett O (2012) Metal theft. Standard note no. SN/SHA/6150, House of Commons Library, London

Lott JRJ, Mustard DB (1997) Crime, deterrence, and right-to-carry concealed handguns. J Legal Stud 26(1):1–68

Loughran TA, Paternoster R, Chalfin A, Wilson T (2016) Can rational choice be considered a general theory of crime? Evidence from individual-level panel data. Criminology 54(1):86–112

Matsueda RL (2013) Rational choice research in criminology: a multi-level frame- work. In: Wittek R, Snijders T, Nee V (eds) The Handbook of rational choice social research. Stanford University Press, Stanford, pp 283–321

Matsueda RL, Kreager DA, Huizinga D (2006) Deterring delinquents: a rational choice model of theft and violence. Am Soc Rev 71(1):95–122

McGill R, Tukey JW, Larsen WA (1978) Variations of box plots. Am Stat 32(1):12–16

Montag J (2014) A radical change in traffic law: effects on fatalities in the Czech Republic. J Public Health 36(4):539–545

Murray MP (1994) A drunk and her dog: an illustration of cointegration and error correction. Am Stat 48(1):37–39

Newey WK, West KD (1987) A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55(3):703–708

Piliavin I, Gartner R, Thornton C, Matsueda RL (1986) Crime, deterrence, and rational choice. Am Soc Rev 51(1):101–119

Posick C, Rocque M, Whiteacre K, Mazeika D (2012) Examining metal theft in context: an opportunity theory approach. Justice Res Policy 14(2):79–102

Posner RA (1985) An economic theory of the criminal law. C Law Rev 85(6):1193–1231

Saikkonen P (1991) Asymptotically efficient estimation of cointegration regressions. Econom Theory 7(1):1–21

Sheather SJ, Jones MC (1991) A reliable data-based bandwidth selection method for kernel density estimation. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Stat Methodol) 53(3):683–690

Sidebottom A, Belur J, Bowers K, Tompson L, Johnson SD (2011) Theft in price-volatile markets: on the relationship between copper price and copper theft. J Res Crime Delinq 48(3):396–418

Sidebottom A, Ashby M, Johnson SD (2014) Copper cable theft: revisiting the price-theft hypothesis. J Res Crime Delinq 51(5):684–700

Stock JH, Watson MW (1993) A simple estimator of cointegrating vectors in higher order integrated systems. Econometrica 61(4):783–820

Tonry M (2014) Why crime rates are falling throughout the Western world. Crime Justice 43(1):1–63

Tsebelis G (1989) The abuse of probability in political analysis: the robinson crusoe fallacy. Am Polit Sci Rev 83(1):77–91

Watkins C, McAleer M (2004) Econometric modelling of non-ferrous metal prices. J Econ Surv 18(5):651–701

Wortley R (2001) A classification of techniques for controlling situational precipitators of crime. Secur J 14(4):63–82

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the following for their helpful comments: two anonymous reviewers, Richard Boylan, Jan Broulík, Pawel Bukowski, Pavel čížek, Brendan Dooley, Jakub Drápal, Libor Dušek, Jitka Dušková, Oren Gazal-Ayal, Martin Guzi, Petr Koráb, Peter Huber, Marek Litzman, Guido Maretto, Giovanni Mastrobuoni, David de Meza, Nikolas Mittag, Marie Obidzinski, Daniel Pi, Amos Witztum, and participants at the 2016 Conference on Empirical Legal Studies in Europe at the University of Amsterdam, the 2015 conference of the Society for Institutional and Organizational Economics at Harvard University, the 2015 conference of the European Association of Law and Economics at the University of Vienna, the 2015 Law and Economics Workshop at Erasmus University Rotterdam, the 2015 Young Economists’ Meeting at Masaryk University in Brno, and the 2014 Annual Meeting of the German Law and Economics Association at Ghent University. We are grateful to Arnošt Danihel, Vladimír Stolín, and Bohuslav Zúbek from the Police Presidium of the Czech Republic for providing us with crime-level data on metal thefts. Parts of this paper were written between April and July 2014 while Josef Montag was a visiting researcher at the Tilburg Law and Economics Centre at Tilburg University; he gratefully acknowledges the centre’s hospitality, support, and valuable discussions with TILEC’s faculty and researchers. We also thank Annie Barton for careful editing. All remaining errors are our own responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Josef Montag: The data and code producing results reported in this paper are available at http://sites.google.com/site/josefmontag or upon request.

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 5.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brabenec, T., Montag, J. Criminals and the Price System: Evidence from Czech Metal Thieves. J Quant Criminol 34, 397–430 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9339-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9339-8