Introduction

The sourcing and verification of eyewitness content has become central to how newsrooms tell stories from conflict zones, and, in the immediate aftermath of breaking news events, allows journalists and their readers to get closer to the story.

Eyewitness content is also used in holding violent actors to account. At times, perpetrators themselves publish content, either unwittingly or for propaganda purposes, that can become central to how a story is told, or how criminal activity is prosecuted.

The International Criminal Court in 2017 issued its first arrest warrant to draw primarily on social media. More broadly, journalists and human rights investigators draw on social media to research or to shine a light on abuses and to advocate for action to be taken to bring perpetrators to justice.

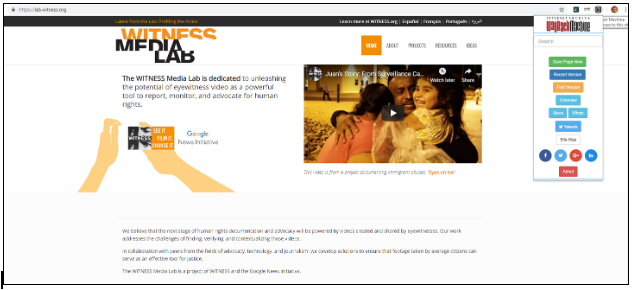

This report is concerned with the sourcing, monitoring and analysis of perpetrator-created content, with reference to ethical considerations relating to the collection, handling and distribution of such content for use in human rights monitoring and reporting.

This report is a collaboration between WITNESS and Storyful that seeks to answer WITNESS’s core question relating to perpetrator-created content: how do we use these videos to our advantage without becoming amplifiers for the abusers and putting people in greater risk?

Storyful’s extensive experience of building networks of reliable sources, and of finding and verifying social media content allows us to set forth techniques that allow for timely, relevant reporting on abuses and crimes, through the application of a replicable methodology, applicable to a range or topics, localities and conflict zones.

Two case studies included in this report will set out how that methodology was applied by Storyful in reporting on perpetrator content from two very different stories from conflict zones in Syria and Iraq.

How such content is used will differ based on the needs of the user: journalist, advocacy worker, prosecutor, etc. In each case, it is necessary to minimize the harm that could be caused by exposing or reporting on such human rights abuses.

WITNESS describes perpetrator content as content taken by an actor or “at the scene of an incident, with the express intent to do harm.” An eyewitness to the action, filming and distributing content with the same intent can also be a perpetrator. Harm, by WITNESS’s definition, includes the intent to “spark fear, promote hate, dehumanize an individual or community, glamorize violence, recruit new members to an organization, entertain abusers, share tactics, or confuse/mislead.”

Relevant Reporting

A controlled approach to content discovery is key to developing insights, sources and search techniques that allow the individual or a team to monitor a story, location or topic over time. This approach is replicable but would need to be tailored to the topic.

Understanding the Media Environment

You must first build an understanding of the media used by perpetrators, by their target audience, and by actors seeking to counter perpetrator messages, as well as to understand, where possible, the motivations of those involved in the dissemination of such content.

Case Study 1 below, for example, involves content shared by perpetrators as well as by activist groups seeking to raise awareness of the issue. Tracking the activities of both parties and understanding their motivations is central to building an understanding of the situation.

The key question to ask is where would someone involved in the creation of activist content in a certain location be most likely to share that content in order to meet their aims?

What motivates a perpetrator to publish publicly on social media, as opposed to privately on a content-hosting or archiving site? How would media attention or the policies of social media platforms themselves impact a publication strategy for a militant group, for example?

Over time an investigator or journalist can build an understanding of where, how and why content is posted. This understanding acts as a filter, allowing faster access to content that is closer to the original source.

This understanding must adapt to changing patterns, stricter social media monitoring by the platforms, or other changes.

The approach to searching for footage from violent actors in conflict zones will often differ from that used to search for extremist content in Western nations. Searches may include a mix of traditional and fringe social networks, including:

- YouTube

- Snapchat

- Telegram

- Gab

- 4chan

- 8chan

- Endchan

- Voat

Different strategies will be needed for different platforms, based on the nature of the content, the violence, or the criminal activity being considered.

You must understand and adapt to online conversations to source relevant, original content quickly.

Ethics of Interaction

In order to track perpetrator conversation and publication activity, it is necessary to have active accounts on all relevant platforms and to build alerting methodologies using all available tools. From this monitoring process, hashtags, keywords, colloquialisms, and phrases can be harvested to allow for content searches.

While it is best practice to always, ordinarily, communicate your intentions to sources and uploaders, stating to them clearly the terms of use and the permissions being sought in the uploader’s language, the same cannot be said when it comes to perpetrator content.

Facebook community page administrators, activists groups and independent activists will be open to engaging with requests. However, reaching out to fighting groups and armed militias is discouraged. There is a risk the outreach may draw unnecessary attention to the researchers or to local sources that provided content or information as part of an investigation, or draw attention to victims visible in perpetrator content?

Perpetrator content is often publicly available, that is, published by a party, actor, or group for public dissemination, and often with the intention to do harm or for propaganda purposes. Observers should consider whether the benefits of publication or dissemination, whether by journalists or by human rights investigators, outweigh the risk that doing so will further the aims of the perpetrator.

If publication or dissemination is warranted, other considerations arise. Can you identify the victims to seek their consent before sharing the content? If you can identify them, could others, potentially to their detriment? Would publication or dissemination of the content put the victims, their families, or their wider communities at risk? Further discussion on this topic can be found in the ethical use of perpetrator content section.

Consider also the risks to which you may be exposing a source in reaching out to them publicly, or even privately. Set out rules of engagement for such public outreach for your team.

Also set out ethics guidance on how your organization’s team members will behave and be identified on social platforms, to avoid them misrepresenting their role or intentions online. It is important to be transparent and upfront in conversations with sources or content uploaders.

On traditional social platforms (Twitter, Facebook, etc) create user accounts that clearly identify who is behind the account and explain why you are reaching out to someone. Using closed platforms and messaging services, such as Telegram, WhatsApp, or similar platforms, is different: the user accounts are more easily made anonymous. When trying to gain access to groups or chats on such apps, does each member of that group understand the implications of sharing content with you?

Where publicly contacting a source may put a journalist or investigator at risk, shared accounts under the organization’s name may be appropriate.

If, while reaching out, you don’t identify either your name or your organization’s name, the work effectively becomes an undercover investigation. Extraordinary circumstances are required before such an approach is taken and, again, your organization should set out clear rules for the team to avoid the possibility of deceiving a source or misrepresenting the work.

Role of Citizen Video

Content discovery

The outcome of an analysis of the media environment should be:

- An understanding of the platforms used

- An understanding of the language used

- An account of relevant:

- Hashtags

- Keywords

- Colloquialisms

- Phrases

- A set of accounts to follow and monitor

Below, we will set out the methodology for sourcing, archiving, and making sense of content on these accounts.

Developing sources

Establish reliable sources to more quickly find content, daily leads, and people who can provide corroborating information to help in the verification.

- Reliability cannot be assumed. It must be established over time. Reliable accounts lead to other reliable accounts. Factors to consider include:

- Can content from the source be independently verified?

- Does a source’s reporting tally with multiple independent sources?

- Can the source be contacted directly?

- How do they respond to being challenged on a claim?

- Are they forthcoming with information that can be independently verified?

- Are they transparent about their motivations?

Wherever possible, contact the source to learn where their information and content comes from. Is it realistic that an individual could provide all of the content on a given account? Are you dealing with a network of individuals and, if so, what impact does that have on the validity of their information?

Making direct contact will let you build trust and transparency with a social media source. Be open when communicating with sources and give information about your organization and intention.

The nature of the language while reaching out could vary from country to country, due to the sensitivity of the political conflict in the region.

For example, when working on content from inside Syria, Storyful’s journalists were aware that the conflict was highly complex and sensitive and that Syrian society was polarized. Before reaching out to any party, we asked these questions:

- Who is the uploader?

- Who do they support?

- Are they a media activist group or an individual?

- Where are they based in Syria?

- Are they operating in government areas or opposition areas?

- What is their religious and cultural background?

- What is their political stance? Are they pro-opposition, pro-government or neutral?

Content from militias, military forces and government sources can be considered public – provided for dissemination. For all other sources, seek permission before using their content.

Use neutral language in all communications with sources on the ground. For example, avoid using the word “militia” when describing rebels or opposition groups when speaking to uploaders who take a pro-opposition stance. The same should be applied while communicating with uploaders who take a pro-government stance. For example, avoid using the word “regime” when describing a government.

Once a set of reliable accounts has been established, mine them for daily leads and content.

Make use of existing, publicly available sources wherever possible, and work to independently verify information from those sources.

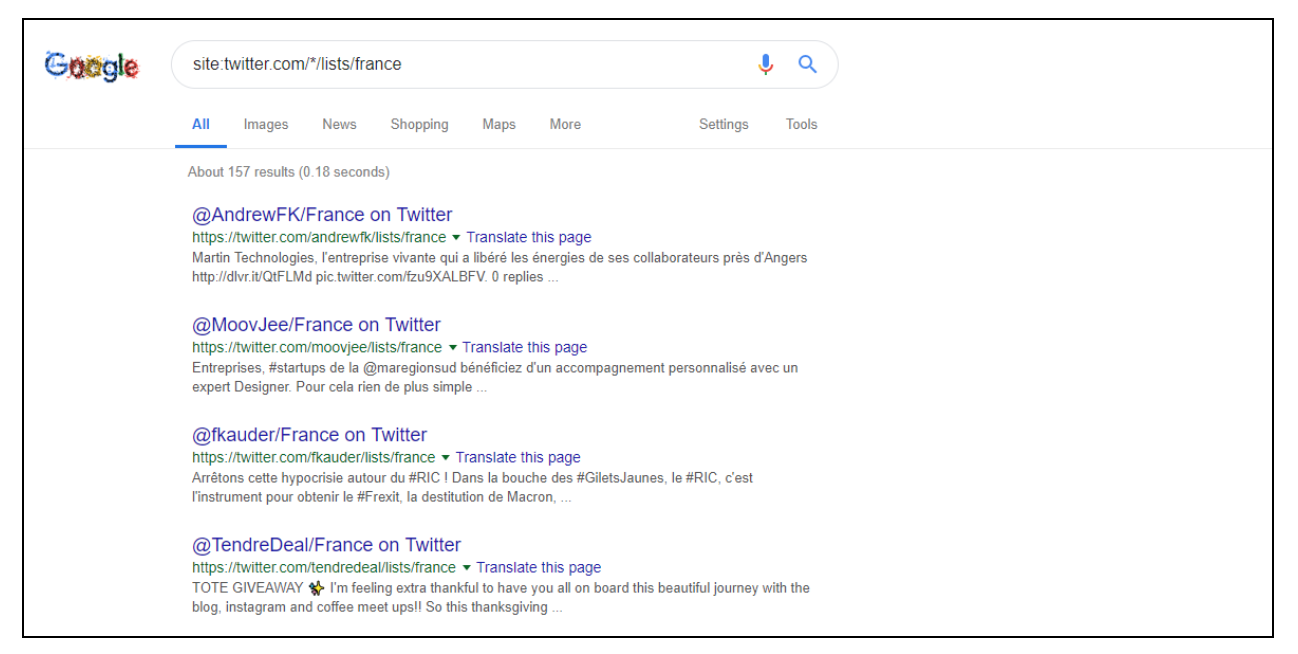

Find relevant lists on Twitter as follows by searching online:

- site:twitter.com/*/lists/keyword

- site:twitter.com/*/lists/*keyword

Account and Search Monitoring

There are multiple methods for list building and alerting across various platforms.

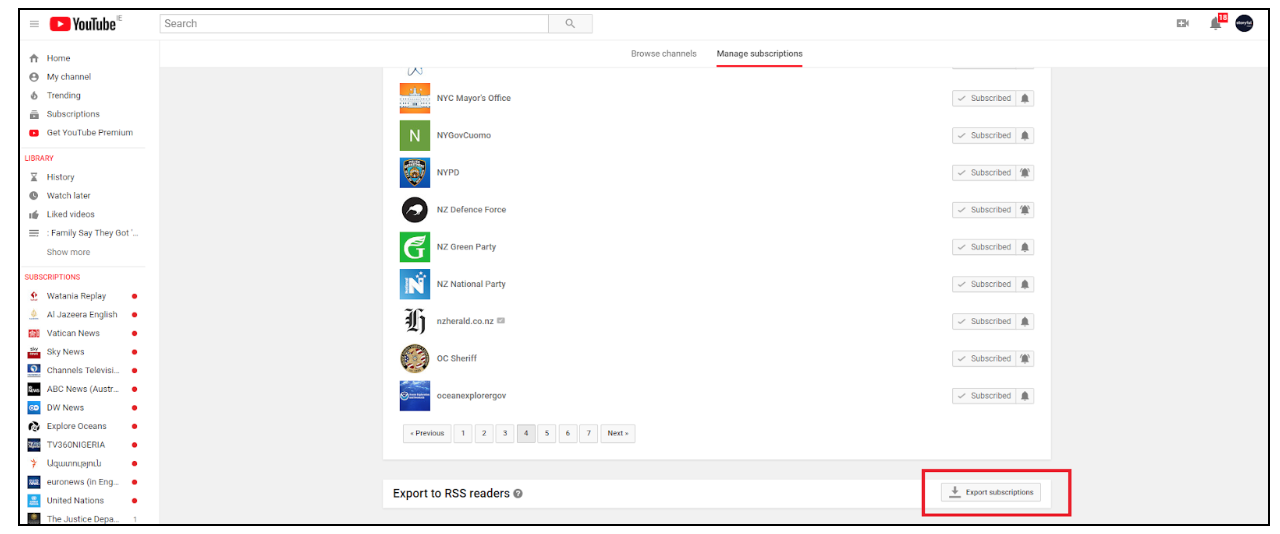

- A list of useful YouTube channels can be created in subscriptions. A subscription list can be exported as an RSS feed.

- Useful Twitter accounts can be added to a list, or a series of lists, and monitored manually or with tools such as Tweetdeck and Hootsuite.

Build systems using free tools to get alerts on content from multiple sources:

- Crowdtangle: Used to build lists of content from sources on Facebook (pages or groups), Instagram, Twitter (accounts or lists) and subreddits

- Powerful for monitoring all content or for watching for spikes in activity

- Set up email or Slack alerts from inside the app

- Feedly (or another RSS reader): Used to build lists from YouTube subscriptions, from websites or from audio feeds.

- Used to monitor news feeds and subscriptions.

- Google Alerts: Set up alerts for search terms (keyword), for instances of keywords on a given site (site:website.com keyword), and for handles of accounts for sources you have already developed.

Centralize alerts from various platforms via email alerts, Slack integrations, etc, based on the needs of the team or project.

Manual searches

Using your relevant source lists, scan for content, stories and topics. From these, develop relevant keywords: locations, terms, topics, and colloquialisms. You should build a profile of what you’re looking for – the who, what, where, when. This data set will differ for theme and topic, but once established give you a starting point for searches.

Use these terms to search for video on the known, most-used platforms, for content and for relevant reporting.

This process should be systematised — conduct a sweep of sources each day or multiple times each day to ensure all relevant leads and content are captured for analysis or archiving.

It is key to understand what people are saying and how they are saying it. Be specific with keywords:

- Don’t use words or phrases that are too common, this will create noise

- Whenever you can, use the street names, building names, and other terms used locally

- Are religious phrases used?

- Are derogatory terms used for either victims or perpetrators?

- Are common misspellings or slang terms used?

- Understanding what hashtags are being used is key to tracking stories on certain platforms, but drop the # symbol when searching manually across platforms — this increases the range of results.

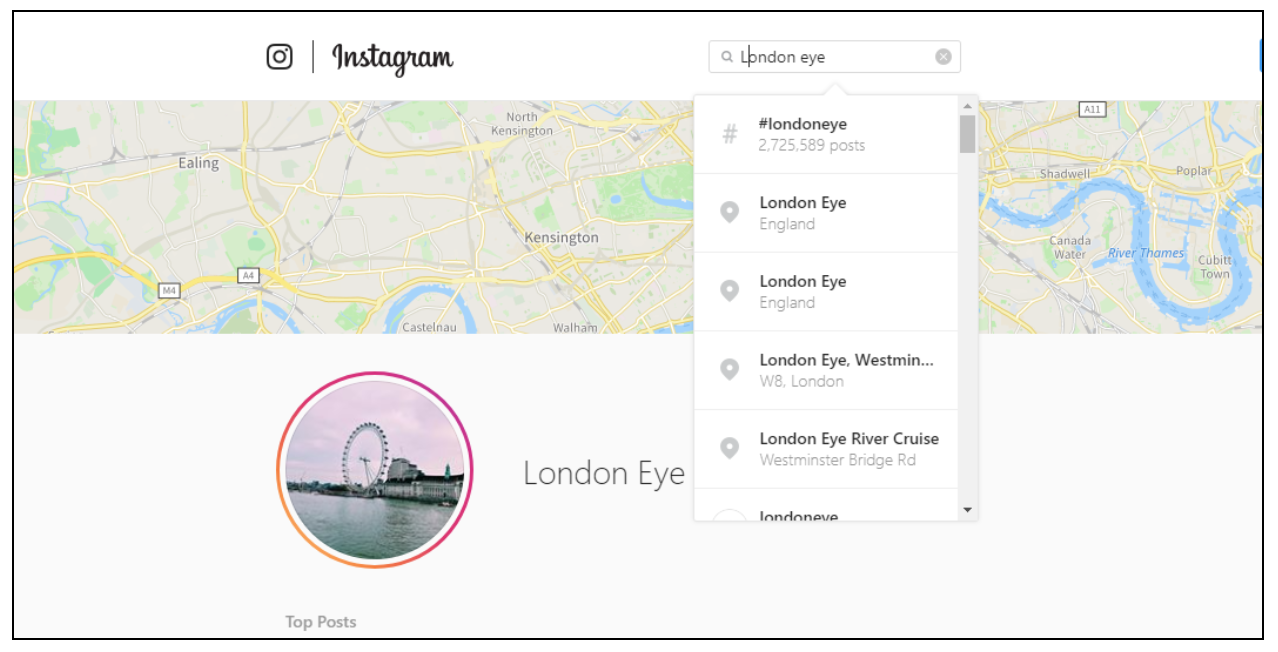

- Platforms have different idiosyncrasies. Instagram concatenates keywords into one search term, for example, so understanding platform limitations is key to tailoring searches. On Instagram, a keyword search for the phrase “London Eye”, for example, will return results for the concatenated term “LondonEye”, rather than an AND search for the two keywords separately. In this case, then, it would be better to search for content geotagged to the London Eye’s location, or to consider alternative keywords.

- Use Boolean operators or advanced search tools on each platform, where available, to get the best results.

Create your own index of useful terms with associated translations. In order to share terms and replicate searches systematically across a team or over time, log terms, translations, slang terms, common misspellings, etc, in a spreadsheet, or build logs of saved searches on platforms such as Twitter and Google for easy replication.

Daesh or Daish (داعش), for example, the Arabic equivalent to the acronym ISIS, is a term that is widely used in the MENA region as a descriptor for Islamic State. The term has negative connotations in Arabic. Therefore, IS media arms and supporters will never use this term.

Different platforms are preferred in different regions, and serve as a good starting point for manual searches, though, of course, there are exceptions. The following guide may prove useful:

| Region | Primary Social Media Platforms |

| Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Iraq, Israel, Yemen | Facebook YouTube |

| Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Oman | Twitter YouTube |

| Egypt, Sudan, Libya, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Mauritania, Western Sahara, Somalia, Djibouti, Comoros | Facebook YouTube |

This methodology will return leads and content worthy of further investigation.

Finding and Recording Metadata

Applying the leads and content worthy of further examination.

Your results will constantly improve through a circular process that involves: starting with reliable sources for leads; methodical searches of key platforms based on an understanding of the preferred means of communication; expanding, curating and perfecting those searches based on new information gained throughout the process.

From there, seek original content and corroborating information to get as close to the sources and the story as possible.

Systematically logging metadata associated with a piece of content should be your goal. This metadata will vary based on how close an investigation can get to the original of any piece of content.

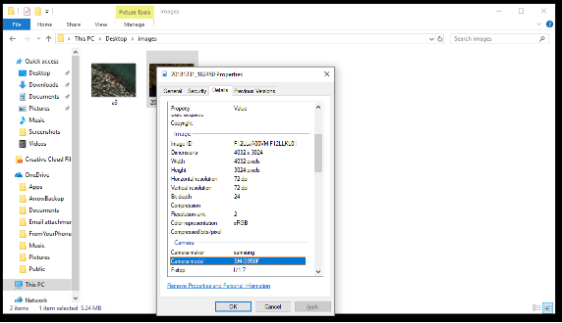

An original photo or video sourced directly from the owner, or via an archiving or FTP website, may contain original technical metadata about the camera, phone, time and location. Though this should not be trusted implicitly, it may provide some useful starting point for verification.

There are websites and tools that can provide the metadata for some videos and photos. Source the original file to get accurate metadata.

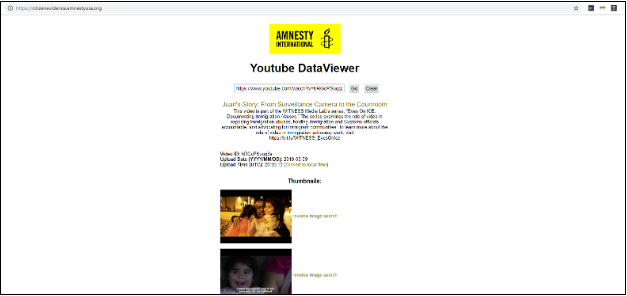

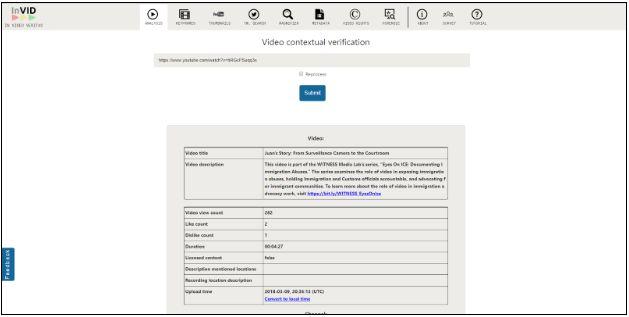

- Amnesty International DataViewer

- InVID: YouTube

- GooFile: Video

- FotoForensics

- Jeffrey’s Image Metadata Viewer

- Get Metadata

- Media Info

Perpetrators often disseminate content on social media and, as such, the content will be stripped of original technical information, but will gain metadata relating to upload time, date and location as well as information about the source that can be useful in the verification process.

You can develop a third layer of metadata during the content-verification process, establishing relevant information about the source, date and location of a given piece of content.

A schema for the archiving of content and associated metadata is set out below.

The Verification Process

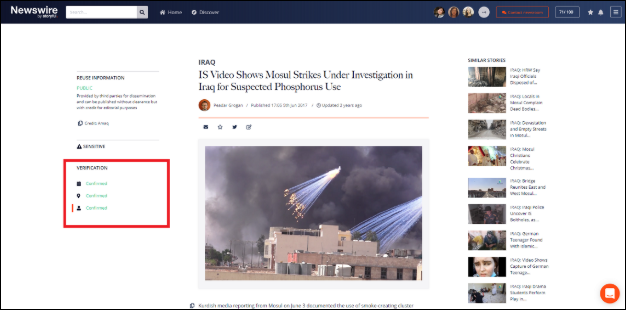

Storyful’s verification process seeks to establish the original source, date and location for each piece of content using all available open source tools and techniques. Storyful categorises content in terms of three levels of verification: Checking, Corroborated and Confirmed.

The verification process can be more clearly seen in the case studies below.

Date

For any piece of content, sort search results chronologically and replicate the keyword searches across platforms – Do you have the earliest instance of the video?

Use reverse image search on thumbnails, key frames, on-screen logos, etc. Look for earlier versions of the video, or old reports about a similar incident from which the video may be taken.

Do reverse image search or analyse image metadata with:

- Google Image Search – on the web or use Chrome extension

- RevEye – Chrome extension allowing cross-platform image searching

- TinEye

- Jeffrey’s Image Metadata Viewer

You can review metadata on a social video with:

Consider also the number of views, the upload time, the quality of the footage, and the uploader’s username and profile picture. Are the contents, the uploader, the quality consistent with what you’d expect?

If there are no earlier versions, look for hints about when the video was taken: do the weather, time of day, comments made by people in the video, etc, tally with the stated date of the clip? Does the content of the media match reports from independent, trusted sources?

Source

If the answers to the above questions are yes, this may be the earliest source. Are there other ways to find out more about the uploader and people seen in the video?

Review the uploader’s social profile and check for a presence on other channels. Is their publicly available information consistent with the video? Where does the person live? Are they travelling? Is it plausible that they would be at the scene of this incident? Can they be contacted easily? Can they provide an original, raw version of the video?

Use open source tools to monitor their presence online:

- Foller.me – Identify a Twitter user’s friends/associates.

- Graph.tips – Search an individual’s Facebook interactions based on their username.

- Inteltechniques.com – Also for Facebook. See the events a profile has RSVP’d to, places they recommend, places checked into, etc.

In the case of perpetrator video in particular, where an uploader may not want to be identified, what can you learn from the video itself about the uploader or other people seen in the video?

Search for more content that shows the same incident, as it will give a wider perspective. This is central to verifying the source, date and location of the video.

For example, while investigating the suspected chemical attack on the Syrian city of Douma in April 2018, Storyful used multiple videos and photos from the incident to compare and crosscheck the scenes and the information provided to get clearer perspective on the attack, the victims and the perpetrators.

The following independent sources shared videos from the site:

Look at military uniforms, weapons, vehicles or munitions seen in the footage to assess the people seen in the video. Use open source information, such as this site on weapon types used in the Syrian conflict. However, information on social media, posted by locals or members of the military, should also be sourced to get up-to-date information from the locality.

If you trace the earliest version of a video back to an archiving site or a closed platform, what can this tell you? Can you find the original post, can you identify the account that uploaded it? Is there an observable spike in conversation, or was the video apparently shared spontaneously by a number of people at around the same time? This may indicate a coordinated campaign.

Location

Verifying the location of a video depends on a careful assessment of unique identifiers: geographic, cultural, clothing, language used, and so on.

Each of these can provide contextual clues to the location or corroborating information.

Search for useful information (street signs, car license plates, buildings, street furniture, etc) that can help you pinpoint an exact location, through search or mapping.

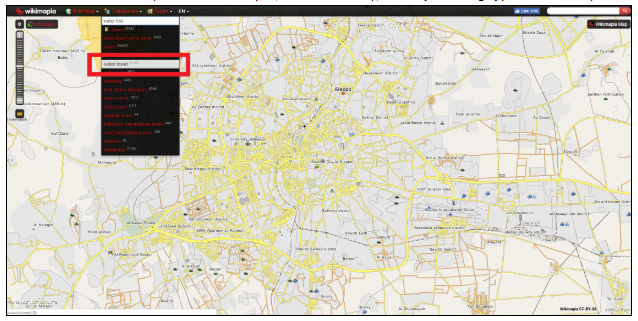

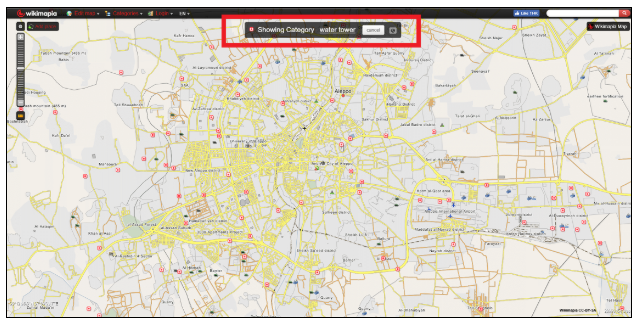

Make use of freely available mapping tools, Wikimapia, Yandex, Baidu, Google Maps, and Bing Maps.

If there are landmarks (such as a mosque, a water tower), filter by building type on Wikimapia:

This will allow you to narrow your search on mapping services that provide satellite imagery or street-level images.

Use advanced techniques to corroborate information in the video – what can you tell from accents, from military uniforms, from weapons used, from vehicles or munitions?

The two case studies appended to this report give numerous examples of geographic verification.

Audience Engagement

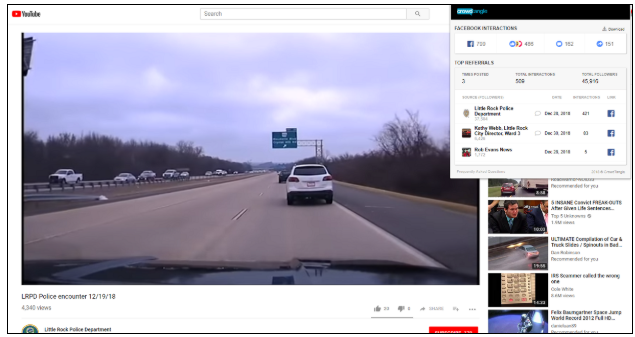

The reach of a given video cannot be exhaustively tracked. Views, interactions, etc, will rarely give an accurate picture in the case of perpetrator video, which is often copied, shared and reshared multiple times.

Due to the nature of perpetrator content, platforms often move quickly to remove videos and close accounts. It is, therefore, difficult to track the reach of originals.

Social data can be used, however, to gain an understanding of the target audience of a piece of content and whether that audience is being reached. It may also be possible to identify key amplifiers of a given video.

Consider the Crowdtangle Chrome extension, which tracks shares of a given link across Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Reddit.

Other services, such as Buzzsumo’s paid social monitoring service, can be used to do more involved metrics analysis.

This sort of analysis is primarily useful in feeding back into building lists of reliable sources of information.

Aggregation of Sensitive Data & Ethical Use

Verified content should be archived systematically.

Download everything. Due to the problematic nature of perpetrator content, videos should be downloaded immediately, since they may be removed by platforms, or an uploader’s account may be suspended for breach of terms of service – even if the content is uploaded for journalistic or human rights purposes.

Archive everything. The original post, if the content originated on social media, should be archived using a publicly available archiving tool, such as:

This will maintain metadata of the post (upload date, etc).

However, while it is recommended that you manually back up perpetrator videos or photos due to the likelihood that they will be removed, Storyful does not advise that this content is stored on publicly accessible archiving sites. This may inadvertently allow for the further dissemination of the content.

Screenshot everything. Screenshot posts, comments, and profiles and log the time that screenshots were taken.

Archiving content and associated metadata

Consideration should be given to the nature of the content. It may need to be hosted offline, ideally backed up to multiple drives, or on private servers, as hosting companies may take issue with such content. However, encrypted online storage options are available and many services provide anonymity and privacy. Consider which service is best for your work.

Such content should be archived in a manner that allows it to be retrieved and linked to other content from the same incident as well as with any associated metadata.

Consider the following schema:

- An ID for each incident (can be shared by multiple pieces of content)

- A unique ID for each piece of content

- A unique url for the archived version of the video

- Time/Date data:

- Time/Date acquired

- Time/Date uploaded

- Time/Date of incident – from verification process

- Location data:

- Location from metadata

- Location from description

- Location – from verification process

- Geo-coordinates (where location has been confirmed through verification process)

- Source data:

- Uploader name

- Uploader account url

- Original source name – from verification process

- A link to archived information (online archive files, screenshots,etc.)

- Discovery data

- Keywords, hashtags, caption, description

- Ancillary data

- Platform, video quality, shares, other versions, audience engagement data (where available).

Ethical use of perpetrator content

Collecting and analysing perpetrator content raises several ethical concerns, both in terms of the potential impact on journalists or investigators, and because of concerns relating to the use and dissemination of such material and the risks to the safety and dignity of those involved. This is particularly important for journalists or archivists intending to report on or catalogue human rights abuses.

Consideration to the journalist, analysts or investigators involved in a project:

- Are individuals prepared for the kinds of content they’ll be exposed to?

- Are individuals given adequate support – training, counselling, etc?

- Is the workflow such that an individual can step back from the work without impacting the project?

- Is the team staffed up to allow members alternate between tasks, or to ensure no one person is overexposed to difficult content.

Consideration should be given to how to store and archive the content:

- As discussed above, sensitive content should not be archived on public platforms or shared for any purpose not central to the project or investigation.

- Storing sensitive content on video platforms or commercial servers risks the content being shared and may raise problems from service providers.

Consideration should be given to the victims and individuals involved:

- In the case of perpetrator video, the content will have been published intentionally for public dissemination. As such, the original source’s consent is not required for publication; however, if victims can be identified, it should be considered whether they should be contacted before publication.

- Will publishing or making available the content endanger anyone or injure the dignity of those involved?

- Will editing the content to protect victims, sources or individuals impact the validity or verifiability of the content?

- Can the content be archived in such a way that it is searchable and available as necessary, without publication.

Consideration should also be given to the target audience:

- The target audience could be members of the public, journalists, or legal professionals.

- Graphic content should be identifiable and end users should have control over what they’re exposed to when receiving this sort of information.

Before publishing or disseminating the content, it must be verified and archived in a manner that will give the end user all the information they need to take action on the content in an informed manner. This should include information that will ensure the target audience avoids creating problems for the victims, their families, or their wider community through publication or dissemination.

Consideration must be given to whether publishing or using the content will inadvertently fuel tension or possibly lead to an escalation of violence, or risk to the victims.

Storyful’s journalists approach these stories cautiously, providing partner newsrooms with the information they need to tell the stories accurately and confidently in the style and format that meets their own editorial and ethical guidelines.

The verification processes set out in this report is applicable to newsrooms and investigators and is designed to prevent misreporting or wrongful use of content of this type.

Storyful’s policy is never to publish perpetrator content publicly (though we archive and provide such content to partners).

In order to protect the integrity of our work, Storyful considers offering anonymity to sources only where there is a compelling case to do so, such a potential threat to life, liberty or security.

Storyful has specific policies around the publication of content that shows minors (parental releases may be required), or where the blurring of faces, muting audio to protect sensitive information, etc, may be necessary. In our role as a newsroom-to-newsroom service provider, our partners are the ultimate arbiters of how this content will be used.

Storyful cannot provide legal advice on these matters to newsrooms or investigators. Individual newsrooms will be bound by local legislation with regard to the right to a free trial, privacy and other concerns. Storyful’s role is to provide detailed information to our partners to allow them to make informed decisions about usage.

Risk Assessment

The goal of publication of content by journalists or human rights organizations is to draw attention to an issue, or to prompt action by authorities to deal with the situation or bring perpetrators to justice. Consider the following:

Public Interest vs Individual Risk

- Will the publication serve the public interest, but put an individual at risk? Storyful would not advise that content be published in such cases.

- Is it possible to tell the story in a different format, or, for human rights investigators, can the case be handed over to authorities for investigation without publication?

- If there is a strong public interest case for publication, can the uploader or the victim be identified? If so, can their identity be obscured while still allowing their story to be told?

Public Interest vs Rights of the Accused

- Will the publication serve to draw attention to an issue, but put prosecution at risk where the perpetrator is identified?

- In the case of a high-profile perpetrator, there is a case to be made for the publication to force the authorities to take action. The case of Mahmoud al-Werfalli, a Libyan special forces commander wanted by the International Criminal Court, is an example where social media content, in which al-Werfalli was clearly identifiable, was central to the prosecution.

- There is a strong case for publication in the public interest where the content is verified and the source is a public figure, if the goal is to draw attention to the issue or the crime.

- However, the rights of the accused also need to be protected. Depending on the case and the circumstances, blur faces or take other steps to insure the story can be told without prejudicing prosecution.

Public Interest vs Individual Dignity

- Will publishing a piece of content result in greater advocacy or better long-term results for a victim than would otherwise be the case, even where publication would impact the person’s privacy or dignity?

- Special consideration is given to the following cases:

Children: Children are highly vulnerable, so respecting their dignity and privacy is vital. It is important to obtain permission and consent from parents for all photos and videos used for publication.

UNICEF’s guidelines for journalists reporting on children recommend to “always change the name and obscure the visual identity of any child” that meets the following criteria:

- Is a victim of sexual abuse or exploitation

- Is a perpetrator of physical or sexual abuse

- Is HIV positive, or living with AIDS, unless the child, a parent or a guardian gives fully informed consent

- Is charged or convicted of a crime

Women: Considerations around women and their safety are particularly relevant in certain regions.

As the status of women varies widely from city to city and country to country, special considerations should be taken when reporting on such cases of abuse.

In some places, a woman’s “honor” can be important to her family or society, increasing the risk that identifying a female source or victim could lead to reprisals or put such people at risk of death. Women can become “double victims”: they may be victims of the perpetrator, as well as victims of the tradition and rules of their society, or may become victimised as a result of being the subject of reporting or an investigation.

The fear of being subjected to blame and public criticism if they are named in the media can lead people to decide against speaking up about their experiences. It is important that the use or publication of perpetrator content does not add to the factors that constrain a victim’s ability to speak out.

Prisoners: Videos of prisoners often show them in vulnerable situations. Perpetrator-created videos sometimes show prisoners being humiliated, degraded or even tortured.

Videos of this kind are often shared with the intent to warn a community of the consequences of disobeying orders, or as acts of dominance over a defeated enemy.

Perpetrators may want to start negotiations with the families of the prisoners, as set out in the first case study below.

Specific cases, such as that of the IS-captured British journalist John Cantlie, kidnapped in Syria in November 2012, raise specific questions. Cantlie appeared in a number of propaganda videos, one of which is discussed in the second case study appended to this report.

Storyful’s policy is never to publish directly content relating to Cantlie; however, we have archived, verified, and distributed his work to our partners. Newsrooms reporting on these video releases often use screenshots or even video clips, in order to illustrate Cantlie’s statements or to report on his location.

Considerations for Survivors of Sexual Abuse

Victims identified in perpetrator content may have been subjected to sexual abuse or exploitation.

Consider the following points in dealing with content in these cases:

- Anonymity (unless the person chooses otherwise after getting advice from a legal advisor).

- Only adults can make an informed decision about how they want their identity to be reported.

- Children’s identity should not be reported, even if they choose not to remain anonymous.

- Don’t share any information that, taken as a whole, could lead others to identify the survivors, such as names, personal details, nationality, hometown, or age.

- Use non-judgemental language in reporting and while conducting interviews or outreach.

- Maintain dignity, confidentiality and respect.

Where appropriate, in each of the cases outlined above, consider not providing the full name of the victims, blurring content for public distribution, etc, while carefully documenting the facts for archival purposes.

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma spoke to journalists and trauma experts in 2016, who provided useful information for journalists, on both self care and on working with and speaking to the victims of child sexual abuse.

Introduction

Fighters with Islamic State (IS) launched a surprise attack on the Syrian city of Sweida and nearby villages on July 25, 2018, killing at least 240 people and injuring more than 170. During the attack, IS fighters kidnapped 30 people from towns in eastern Sweida, comprising 22 female captives, women and girls, and eight male captives, mostly children, but including one young man, according to local reports. Following the attack, videos circulated on social media that showed a number of people, ostensibly in captivity, who were described as those captives.

The videos were sent to family members of the captives to begin and then maintain a process of negotiation with the Syrian government.

Purpose

Storyful’s interest in the story was journalistic: what could we find out about the victims, their families, or their captors through an analysis of open source material, in order to tell their stories?

The investigation posed a unique question: how could we link the women in the videos to Sweida, and could we contact them or their families?

The initial videos were released through reliable sources; however, they contained limited geographic information or other verifiable information.

This case study explores the process Storyful used to verify aspects of the story over a number of months. It sets out how Storyful established reliable sources who were disseminating the IS material for their own purposes; it explains how Storyful sourced the videos and verified the identity of the hostages by building corroborating information and leads over time.

Outcome

Storyful identified the women seen in some of the videos, and by watching the story develop over time, showed that those women were from Sweida and identified sources on the ground who could provide corroborating information.

As a result of Storyful’s reporting, a number of named individuals (activists, reporters, and the women themselves or their families) became sources for partner newsrooms in telling the story, or investigating the hostage-taking. We catalogued and archived a series of videos showing the victims.

This case study deals with content of a sensitive nature. The videos are not graphic, but the hostages are clearly identifiable in them. While this meant that Storyful was able to establish their identities and follow their stories, it presented ethical challenges about how those stories should be publicised.

Methodology

This case study discusses the ethical challenges mentioned above, and sets out the methodology used to build a process for a story of this type, defined by WITNESS for the purposes of this report as a Model 1 investigation – the investigation of a single incident.

Investigating the capture of the Sweida hostages required a months-long process of:

- Identifying local, trusted sources

- Building search terms

- Analysing comments on key videos

- Working to verify videos where there is limited geographic information.

Relevant Reporting

Following the IS attack on Sweida, local sources reported on the abduction of civilians.

Storyful’s years of reporting on the war in Syria allowed us to create lists of reliable sources, catalogued for internal use with relevant information: names, translated names, logos (where appropriate), associated locations and areas of coverage, associated accounts, and notes on affiliations or political links.

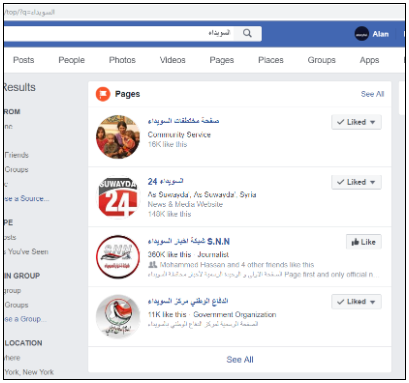

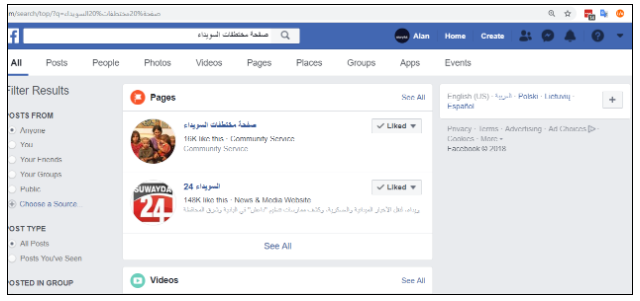

This methodology informed our approach to covering this incident. Facebook is by far the most used and most popular social media platform for Syrians. Starting with simple translations of the word Sweida into Arabic, Storyful used that word to search for local Facebook accounts, including pages and groups, to help with monitoring for updates on the hostages.

The search below shows popular Facebook pages that post daily news and are associated with Sweida.

We also looked at pages and groups associated with the Syrian minority Druze population in the city. We searched the Arabic word Druze (الدروز) and added a number of Facebook pages to our lists. We monitored these Facebook pages on daily basis.

This process gave us early alerts to reports and content emerging on the story.

Role of Perpetrator Video

Hostage-taking during a conflict is a war crime. IS used the hostages captured in Sweida to negotiate for the release of prisoners held by the Syrian government.

During the negotiation process, IS fighters produced, or allowed the release of, a series of photos and videos showing some of the captives.

In the videos, women are seen asking that the government acquiesce to the IS demands for a prisoner swap.

Three videos showed woman:

- Video 1: Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar, named locally (report archived here)

- Video 2: Fadya Abu Ammar, named locally (report archived here).

- Video 3: Abeer Shilgeen and Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar, named locally (report archived here)

These three videos posed a single challenge: could it be proven that they showed women taken during the Sweida assault?

Storyful was able to affirm that they did, despite the limited corroborating information available in the footage itself. This was done by tracking the story over time, identifying reliable sources and family members of the hostages.

The names the women gave in the videos were on lists of hostages released by local activists. The women seen in the videos matched photos circulating locally, and one of the women appeared in two of the videos.

This series of videos posed unique ethical issues. The videos were released with the intent of furthering the aims of militants, even though they were also shared by activists working for the captives’ release.

Storyful also considered the risk to the hostages and to their families; however, the names of the women, and photos of them, were already widely shared on local media and social media. Nonetheless, Storyful did not publish the women’s names immediately, and our role became to verify the validity of the videos in order to support accurate reporting by our news partners.

Finding and Recording Metadata

Assessing the videos

Video 1: Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar speaks to camera

- Source: Islamic State via Najeeb Abu Fakher (Activist) (Confirmed)

- Location: Unknown location near Sweida. (Unconfirmed)

- Date: July 28 (Corroborated)

- Archived here.

A video (archive) and photos (archive) of the hostages emerged on local Facebook news and community pages.

To source originals, we searched on Facebook using Arabic terms such as:

- Swedia abductors : مختطفات السويداء

- ISIS abductors : مختطفات داعش

- ISIS organization abductors : المختطفات تنظيم داعش

This returned the earliest known version of the video, which was posted by Najeeb Abu Fakher.

Fakher is an anti-Assad opposition figure from Sweida, who is based in Turkey. He said in the caption that the video was sent via WhatsApp from a committee negotiating with IS for the captives’ release.

IS used the first video of the hostages to start negotiations and sent it directly to a family member, according to activists who shared the video.

One of the women to speak was identified as Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar. She speaks in a local accent and appeals for help from the Syrian government.

“We are with the Islamic State,” she says in the video. “We ask [Syrian President] Bashar Assad and Kinana Huwija to follow the Islamic State demand to release their prisoners and stop the military operation on Yarmouk Basin in order to set us free. If you don’t answer these demands, they are going to kill us. I am Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar, July 28, 2018.”

The reference to Kinana Huwija here relates to a TV presenter who works for Syrian State television (see an archived broadcast here). Huwija was reported by activists (report archived here) to have been involved in negotiating with IS fighters in Yarmouk Camp, Damascus. (See report here.)

Location:

The location of the first video was not verified, due to the limited nature of the footage. The video shows a woman speaking in a dark space with rough walls, apparently a cave. In the background, a light, possibly daylight, can be seen. A review of reporting on the area indicates that Sweida province is famous for caves. (See these reports from 2009 and 2010, archived here and here.)

Local media in Sweida published a list of 30 names (archived here) of the hostages, saying they were kidnapped from the village of al-Shobki during the Sweida attacks. The name Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar was on that list.

Photos posted by other media activists show the same woman standing in front of an IS flag.

Date:

Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar, in the video, gives the date as July 28. The first photo showing her was shared on July 27. The kidnappings were reported on July 25. The exact date of recording was not independently confirmed.

Video 2: Fadya Abu Ammar speaks to camera

- Source: Islamic State via Najeeb Abu Fakher (Activist) (Confirmed)

- Location: Unknown location near Sweida (Unconfirmed)

- Date: July 31 (Corroborated)

- Archived here.

A second woman, Fadya Abu Ammar, appeared in a video circulated on social media on Tuesday, July 31, saying she and other hostages from a Druze village were in good condition.

Abu Ammar speaks in the video in a local accent, and gives the date as July 31. Again, her name was among those on a list of hostages shared by local accounts (archived here).

The earliest version of the video (archived here) was again found on Najeeb Abu Fakher’s Facebook account. He said in the description and the comments that the video was sent to him from the committee negotiating with IS. He said that, for security reasons, he could not provide details on the source.

Location:

This video had very limited geographic information. The video appeared to have been shot in a tent – daylight can be seen and the video was shot against a cloth background.

Storyful looked at the comments posted under several versions of the video on several Facebook pages. This approach allowed us to identify a woman with the same family name, Abu Ammar, who commented on a video (archived here) saying the woman was her aunt, providing corroborating information.

Date:

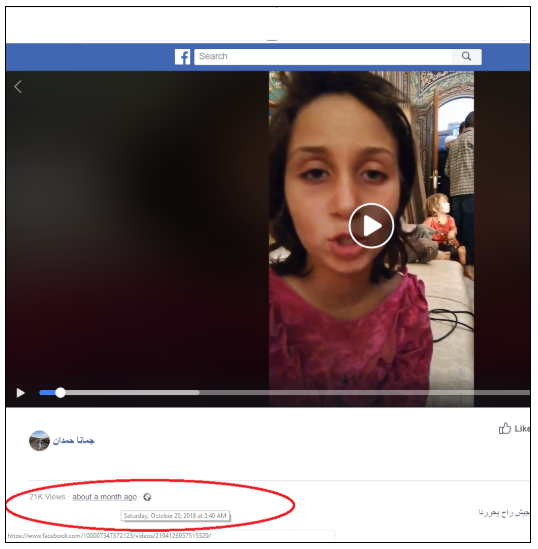

The video was posted on July 31. The woman in the video says the date is July 31.

Local officials and Syrian government representatives were reportedly negotiating (archived here) with IS for release of hostages in exchange for the safe passage of 400 members of the Khalid Ben Walid Army from the Yarmouk basin area to southern Syria.

Video 3: Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar tells stillbirth story

- Source: Islamic State via Sweida Hostages Page (Activist page) (Confirmed)

- Location: Unknown location near Safa. (Corroborated)

- Date: August 12 (Checking)

- Archived here.

A third video emerged on local Facebook pages on August 12. The video (archived here) shows two women, Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar, who appeared in Video 1, above, and Abeer Shilgeen, a woman Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar says had a stillbirth pregnancy while being held captive.

“I am Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar and this is our sister Abeer Shilgeen,” she says. “She was pregnant and gave birth prematurely due to the bad situation. The fetus was born dead. We still live in this bad situation […] We appeal to the brothers in charge to get us out of this situation as soon as possible.” She gives the date as August 12.

The names, Abeer Shilgeen and Suad Adeeb Abu Ammar, appeared on a list of IS captives posted by a local Facebook page (archived here).

Previous reports (archived here) had said that Shilgeen was 33 years old and six months pregnant.

All of the versions of the video were watermarked with the name of a Facebook page.

Using that name in Arabic (صفحة مختطفات السويداء) and we found the page on Facebook (archived here).

The first post on the page appeared on July 27, which indicated the page was only created after the abductions. It is described as a community page and the page shared multiple photos, videos and updates about the captives.

The page shared screenshots of a conversation with Najeeb Abu Fakher, who again acted as a source. He sent them the video directly via WhatsApp (archived here).

Location:

This video had very limited geographic information. The footage appeared to have been shot in a tent and is similar to the previous video.

One of the two women seen in the video appeared in a previous video, indicating that the women were being held together and came from Sweida.

Local sources from Sweida (archived here) reported on August 12 that the hostages were being held in the volcanic hills of Safa, between Damascus and Sweida provinces. The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported that IS transferred the hostages from Sweida province to east Damascus province after the Syrian government advances in the area.

Hostage Releases

On October 20, Abeer Shilgeen and her two children, along with another mother and her two children, were released as part of exchange deal with the Syrian government, Sweida 24 (archived here) reported.

IS released the hostages in exchange for 17 women, the wives of IS fighters, and nine children, who were detained in a Syrian government prison, the report said.

The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (archived here) reported this was the first stage of a comprehensive deal between the Syrian government and IS in which more hostages would be released.

Local Facebook pages gave the names (archived here) of the newly released hostages.

Using specific terms and keywords, as well as the names of the released hostages, Storyful sourced video of the hostages.

- تحرير المختطفات السويداء : Liberating Sweida hostages

- إطلاق سراح مختطفين السويداء : Release Sweida hostages

- تحرير السويداء داعش Liberating Sweida ISIS

- عبير شلغين Abeer Shilgeen

- غيداء الجباعي Ghaidaa al-Jibaai

- يعرب الجباعي Yarub al-Jibaai

The earliest video showed one of the newly released hostages, Ghaidaa al-Jibaai.

That video was shared by a pro-government journalist, Jomana Hamdan. She describes herself on Facebook as from Sweida, and posted several videos and photos from the release, including a live video. The live video was consistent with the other videos and photos, which indicated they were all original. Hamdan shared many photos (archived here) showing her with members of Abeer Shilgeen’s family after Shilgeen’s release.

One of Hamdan’s videos (archived here) shows Abeer Shilgeen with four children after Shilgeen’s release.

A second video (archived here) shows a daughter of Shilgeen, who was taken with her mother. The girl gives her name as Ghaidaa al-Jibaai.

This information was used to verify the identity of al-Jibaai, Shilgeen and Abu Ammar, and by extension the other hostages.

Archiving content and associated metadata

The verification process allowed for the identification of source, date and location of a number of these videos. This was done by following the story through to its completion, the release of some of the hostages, at which point we could verify the identities of the victims.

Storyful archived a series of videos and logged them along with ancillary data, as per the practice set out in the main body of this report.

Ethical use of perpetrator content

IS fighters produced, or allowed for the release of, a series of photos and videos showing captives.

In the videos, women are seen requesting that the government acquiesce to the IS demands for a prisoner swap.

Despite the value of the videos as a propaganda or negotiation tool, they were also shared by activists working to secure the captives’ release. As noted above, Storyful investigated these videos, providing information to our news partners, but did not publish the names of the women or the videos publicly at that time.

This was an instance where concerns for individuals involved in the events shown in the perpetrator video had to be weighed against the public interest argument for publication. The videos alerted the local and international community to the situation of these captives. And public opinion helped spur government action. This was the primary way in which the videos spread online, as conversation about the hostages spurred their circulation.

By releasing videos, IS proved that the hostages were still alive and sent a message to the Syrian government and the hostages’ families about their willingness to negotiate for their release.

Storyful monitored thousands of responses to the videos from Sweida residents. Most locals were relieved to see the hostages were still alive and that led to public pressure on the government to start negotiations. Others criticised IS and what they said was the government’s slow response.

Negotiations with IS to release the hostages broke down several times. During one such incident, IS reported the death of one of the hostages, due to ill-health, according to Sweida 24. IS also shared a graphic video of the beheading of a young man from Swedia, who was reportedly among the hostages, and named as Muhannad Toukan Abu Ammar, مهند ذوقان ابو عمار in Arabic, in local reports, as well as a video described as showing the shooting of one of the women hostages in the head. This led to increased pressure and protest from family members and the local community.

Following the release of the graphic video, families fearing for the lives of the captives gathered in the main square in Sweida, appealing for the government and Russia to work for the hostages’ immediate release.

Videos of the victims were central to public discourse as the story developed, but also stand as evidence of IS crimes and human rights violations, such as the capture and use of hostages for political gain.

There have not been reports that an investigation is underway to identify the perpetrators in this case.

Case Study Conclusions

This case study shows the benefits of taking a structured approach to monitoring a single incident of this kind, applying Storyful’s methodology of building reliable local sources to follow a story as it develops.

Facebook is by far the most used and most popular social media platform for Syrians. Starting with simple translations of Sweida into Arabic, Storyful searched for local Facebook accounts, including pages and groups, to help with monitoring for updates and the breaking news on the hostages.

These local Facebook pages gave the names of the hostages as a starting point.

Keyword searches also allowed us to source the earliest version of the first video.

Verification of the videos depended on analysis of the accents of the women in the videos, and cross referencing with the names and photos shared by local sources.

Monitoring the story as it developed allowed Storyful to build a level of confidence in the reported identities of the victims and the veracity of the videos.

On October 20, some of the hostages were released. Storyful had an archive of related content available for news partners at that point.

In the case of these 30 people, they were named, and their photographs circulated in local media while they were in captivity. The ethical concerns around using content of this kind, where individuals are identifiable, were lessened once those people were released and appeared in the Syrian media.

The following considerations applied to Storyful’s reporting:

- How should the content be archived, so as to avoid sharing IS propaganda? Storyful backed up the material to local servers for sensitive content.

- Will publishing or making available the content endanger anyone or injure the dignity of those involved? Storyful did not publish the videos for public consumption, but distributed them to partner newsrooms via our newswire service for use in their reporting. An approach to reporting on the story would be to make use of the verified information the videos provide, or to use some aspects of the content – the personal stories, for example – without using the names, images, faces or specific requests for government aid seen in the videos.

- Storyful was able to share the content in this manner, with necessary caveats for newsrooms about the kind of available information, and the level of our confidence in that information, helping to inform careful reporting.

Introduction

Since its establishment in 2014, Islamic State has used a highly effective media strategy to spread its message, wage a propaganda war, and recruit adherents online. It has produced material extolling the benefits of life under Islamic State, the power of its military, as well as stories about the supposed victimization of Muslims in Western society. That narrative has focused on the supposed benefits of life under IS rule, including things like its healthcare system; the group’s military power and superiority; its legitimacy in the Islamic world.

IS forces swept into Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, in June 2014. For the three years the city was under its control, IS produced numerous propaganda reports from there, claiming to show the improved quality of life, and the military might of the group in Mosul.

This case study will explore perpetrator content released during the group’s occupation of the city:

This case study will also look at how Storyful’s approach to content discovery and verification was applied to the battle to retake the city, launched by Iraqi forces in October 2016. The city was retaken in July 2017.

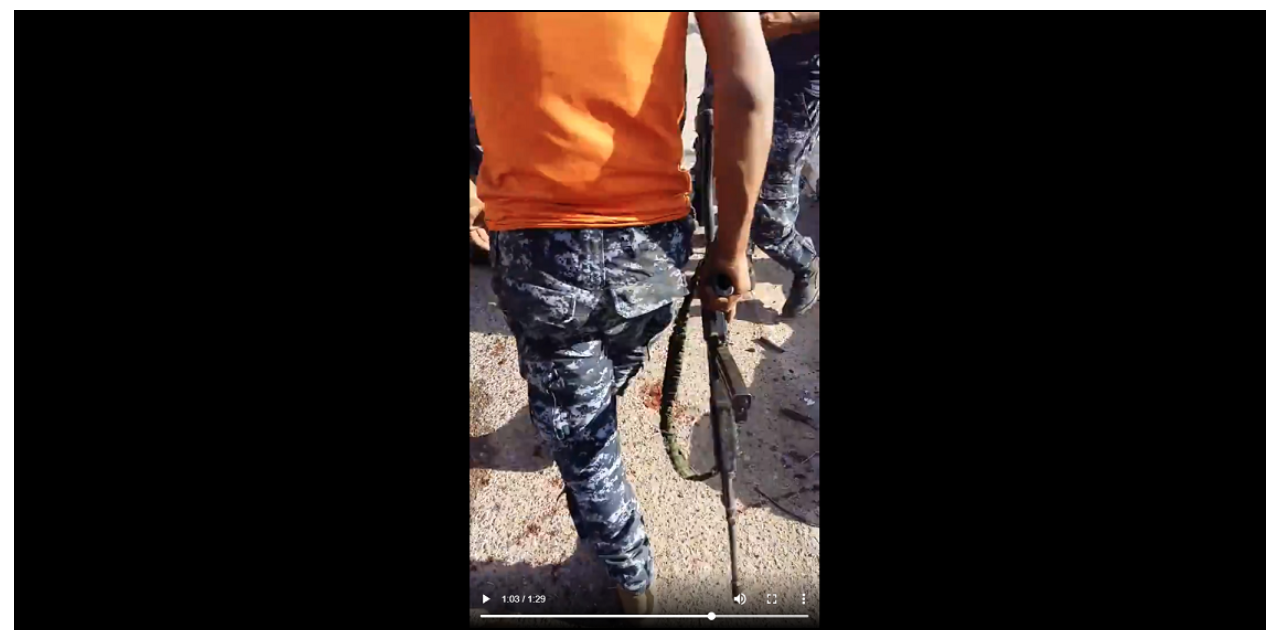

During the battle to retake the city, Storyful applied the same tools to capturing instances of human rights abuses carried out by Iraqi forces and militia groups.

This content was divided into three distinct categories for the purposes of this report:

- Content relating to IS’s initial show of force and military capability

- Content relating to life under IS control

- Content relating to human rights abuses (by IS and others)

Purpose

Storyful’s goal was to source, verify, and archive key content emerging from the large volume of eyewitness- and IS-published media online, and make sense of that content to allow our news partners to tell a coherent story.

We broke the down what we found into three categories:

- Content relating to the initial show of force and military capability

IS content focused on its military strength and ability to take on state forces in asymmetric warfare. Such content was used as propaganda and as a recruiting tool.

The purpose of documenting and verifying this content was to provide news partners with information that either confirmed or contested IS claims of territorial gains, its access to weaponry, and its training methodologies. We were also able to assess the group’s methods of content distribution: where they were publishing content and who was amplifying it.

- Content relating to ordinary life under IS control

As part of its efforts to attract foreign fighters and their families to join the fighting in Iraq and Syria, IS produced various videos showing life inside the city apparently continuing as normal. The videos showed happy citizens, busy markets and the rule of law in the city.

These videos were produced in multiple languages, with speakers representing the many nationalities that joined IS.

Storyful’s goal here was to document the release of this propaganda, and provide news partners with information on where and when the videos were produced, along with information about who made them, and who was involved.

- Content relating to human rights abuses (by IS and others)

Alongside shows of military force and videos showing “normal life” in the city, IS produced multiple videos showing violent reprisals against enemy fighters, prisoner beheadings, and videos showing acts of “justice” carried out against citizens breaking IS’s laws.

Outcome

Storyful monitored the city of Mosul from the time it was overrun by IS fighters, through to the battle to retake the city. During this time, we developed a methodology for monitoring the release of new content.

The result of the work was a feed of useful verified content from inside the city during its occupation. For Storyful’s news partners, this meant verified content, information about the source and their motivations, information about the content itself, the people in the videos and the weapons and tactics seen in the video. Storyful also provided guidance around how the material could potentially be used for reporting purposes. While we deemed most of the content as essentially public domain, or rights free, given how it was produced, and how it was intended for dissemination, we also flagged videos that were graphic, or needed to be treated with editorial caution.

This case study shows how Storyful’s approach to tracking a story like this allowed our journalists to gain an understanding of IS’s media tactics, preferred publishing methods and accounts.

Storyful identified IS’s media arms, including content publishers in each of the militant group’s provinces or wilayats, or centralized publications, including online magazines and weekly newspapers. Some of these are listed below.

This level of understanding was central to quickly finding and making sense of content of this kind.

Methodology

This case study discusses these challenges, as well as setting out the methodology used to build a process for a story of this type, defined by WITNESS for the purposes of this report as a Model 2 investigation – the investigation of a category of content or a broad issue.

The methodology set out here was used to develop:

- An understanding of publishing processes by IS militants

- A means to identify a network of IS regional publishers

- Lists of search terms and processes to find this content quickly

- Processes for archiving and verifying the content.

Useful verification information

Location:

IS was consistent in the publication of produced propaganda videos and usually provided accurate location information. They tended to show obvious landmarks and distinctive buildings and sites.

For example, the video here was filmed in front of Mosul Grand Mosque.

However, battlefield footage or longer video packages were harder to verify, or sometimes contained multiple locations, or footage from third parties.

In terms of describing locations, IS did not use terms like “city” or “province.” They tended to use the term “wilayat” (ولاية), which means a state, and their territory was subdivided into multiple wilayats.

For example:

- Wilayat Idlib – ولاية إدلب

- Wilayat Aleppo – ولاية حلب

- Wilayat Anbar – ولاية الأنبار

- Wilayat Nineveh – ولاية نينوى

Date:

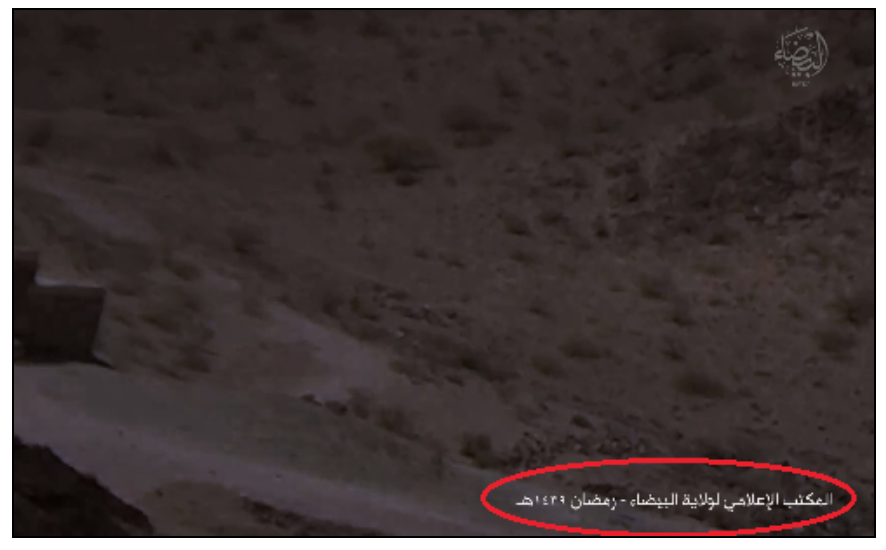

IS content primarily used the Islamic calendar. All of the content shared by the IS media arms, such as Wilayat Bayda, Wilayat Raqqa, Wilayat al-Khair, Al-Furat Media Foundation, al-Naba and Furqan Agency, used Islamic dates.

See examples here:

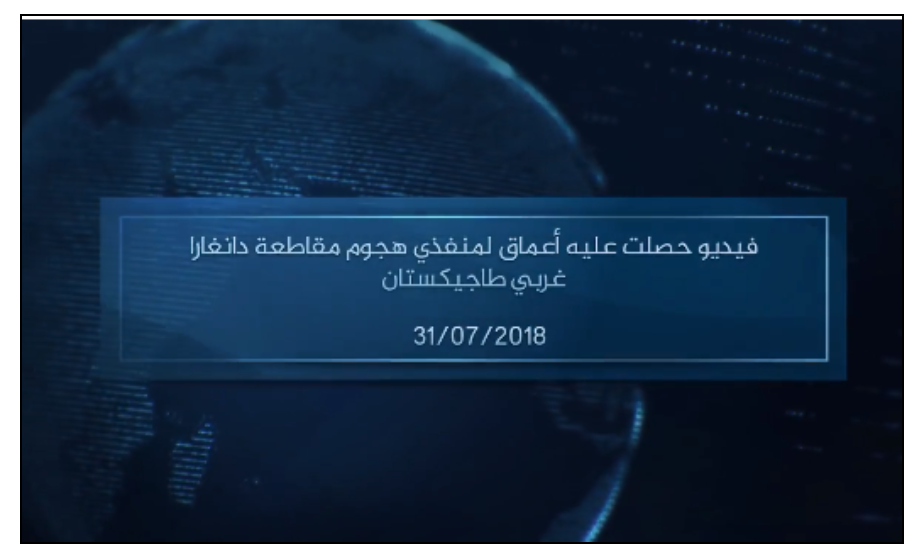

However, the IS-linked Amaq Agency tended to use the Gregorian calendar more than the Islamic one.

For example:

These are some websites that offer a simple method for transforming Gregorian calendar dates to Islamic calendar dates and vice versa.

Relevant Reporting

For its reporting on the story, Storyful developed lists of reliable sources and catalogued them for internal use by name, logo (where appropriate), associated location and area of coverage, associated accounts, and affiliations or political links.

Social media platforms, such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, were widely used by IS and its supporters to spread their ideology and for recruitment. However, social media platforms adapted quickly, banning accounts and removing content promoting the IS propaganda.

This required an approach that allowed for early detection and archiving of new content.

Monitoring IS Content

IS uses specific keywords and hashtags when new content is published. This allows for speedy dissemination of content. Using common terms and hashtags means content can be found and amplified by the group’s supporters, combating the platforms’ efforts to remove content quickly.

The content was traditionally shared on social media platforms, primarily Twitter and YouTube. Some hashtags and keywords used by IS and its supporters included:

- #الدولة_الاسلامية

- #أخبار_الخلافة

- #ولاية_

- #أنصار_الخلافة

- #دولة_الخلافة

- #وكالة_اعماق

- #اصدارات_الخلافة

Note: Daesh or Daish (داعش), which is the Arabic equivalent to the acronym ISIS, is a term that is widely used in the MENA region as a descriptor for the group. The term has negative connotations in Arabic. Therefore, IS media arms and supporters would never use the term.

In response to social platforms’ efforts, IS increased the use of closed networks, content archiving websites and FTP (File Transfer Protocol) websites, such as:

The Wayback Machine is a very useful tool to retrieve suspended accounts and deleted tweets.

Storyful identified a number of IS media organizations, some of which are listed here:

- Amaq News Agency وكالة أعماق

- al-Naba Weekly Newspaper صحيفة النبأ الأسبوعية

- Anbar Media Center المكتب الإعلامي لولاية الأنبار

- Dabiq Magazine مجلة دابق

Specifically in Mosul, the group published content via a number of media organizations, including:

A constant process of monitoring Telegram channels for links to new instances of the Amaq websites, and the websites for links to new Telegram channels, was necessary as web hosting services and Telegram moved to shut down new accounts and pages.

Just by searching the term الدولة الاسلامية (Islamic State) on archive.org, hundreds of pieces of IS content can by found.

Note: It is highly recommended to manually archive any videos or photos released by IS as its content is very quickly removed from social media platforms and websites. Due to the sensitive nature of the content, Storyful does not advise that this content is archived to publicly available archiving sites, although those sites can be useful for the discovery of perpetrator content.

Role of Perpetrator Video

Content Relating to the Initial Show of Force

Most IS propaganda has focused on the group’s ability to take on state military forces with far greater numbers and more advanced weaponry.

Social media was used to announce the group’s spread across parts of Iraq and Syria in 2014, most notably in Mosul where the hashtag #AllEyesOnISIS helped sow fear among citizens and members of the Iraqi security forces in the city. In numerical terms, the military and armed police in the city dwarfed the approaching IS force, but the defenders failed to hold the city.

Displays of power and military force became a dominant strategy used by IS in Mosul. These videos were used as propaganda and as a recruiting tool. Some examples are listed below:

1. Militants Parade Through Mosul in Show of Force

- Source: Islamic State via JustPaste.it (Confirmed)

- Location: Mosul (Confirmed)

- Date: June 23, 2014 (Corroborated)

- Archived here

IS militants paraded vehicles and weapons through the streets of Mosul on June 23, according to eyewitness accounts (archived here). A convoy of IS vehicles carried armed men through the streets. These images, shared by an IS-linked account, were described as showing scenes from that military parade. The militants showed off the weapons and vehicles they seized when the Iraqi army fled.

Source:

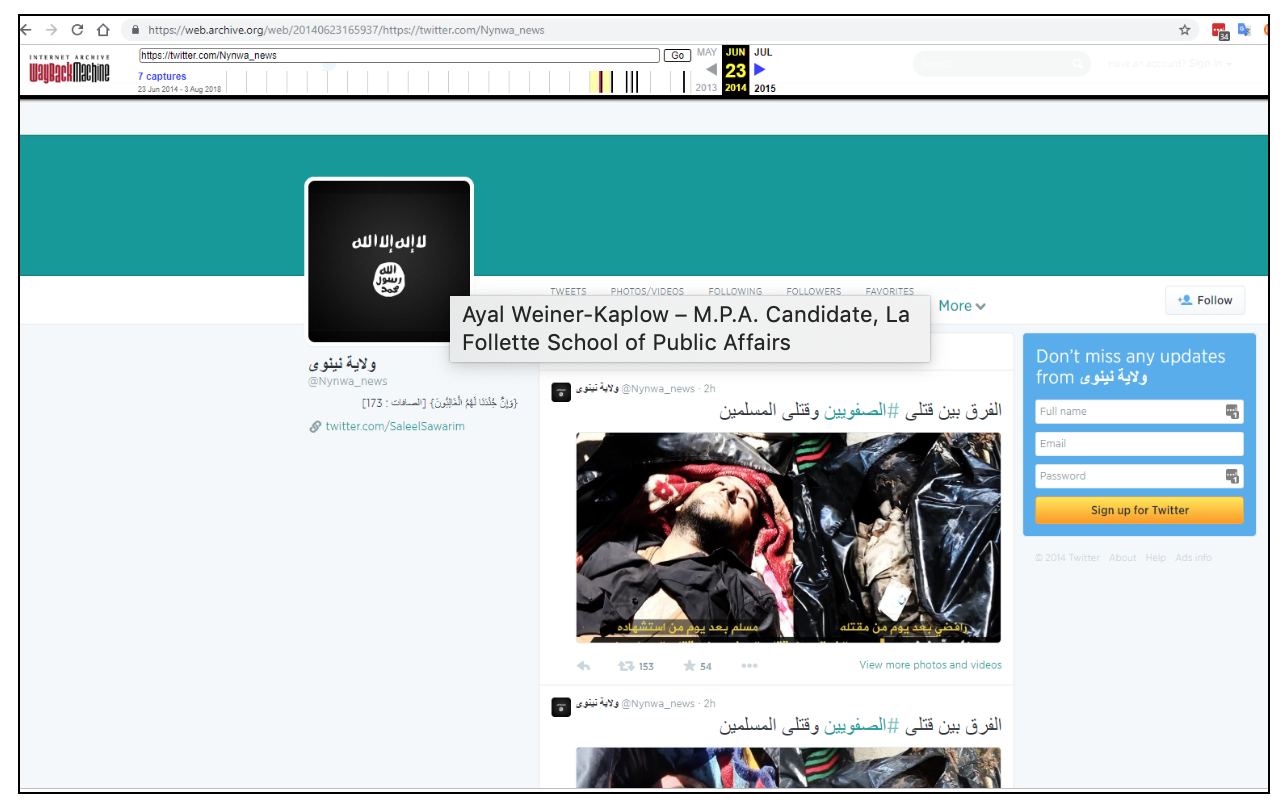

The photos were posted to JustPaste.it, a photo-sharing platforms often used by IS at the time. This particular photo set linked back to the now-suspended @Nynwa_news Twitter account, which was affiliated with IS. That account shared a link to the photos. The account was removed by Twitter. Using the Wayback Machine tool, we were able to retrieve the account and some of the tweets.

The full photo set was available here: but the account was removed quickly.

Location:

While it was not possible to verify the location of each photo, the photos did tally with eyewitness accounts, and at least one of them was confirmed as having been taken in Mosul.

The minaret seen in the final image above tallies precisely with this geotagged image of the Haibat Kahtoon Mosque. The same image shows distinctive lamp posts, which tally with another photo shared on Google Images from that street.

The license plate seen in the first photo above are similar to those seen on Iraqi military vehicles. See examples here, here, and here. This corroborates the reports that IS seized weapons and military vehicles from the Iraqi army.

Date:

These photos were uploaded on and shared on June 24; however, they appear to tally with reports and video from the previous day. This footage, included in a broadcast by ITV, shows a parade of military vehicles in Mosul, which tallies with the images above.

The journalist John Irvine, who was at the scene, also tweeted about the military parade.

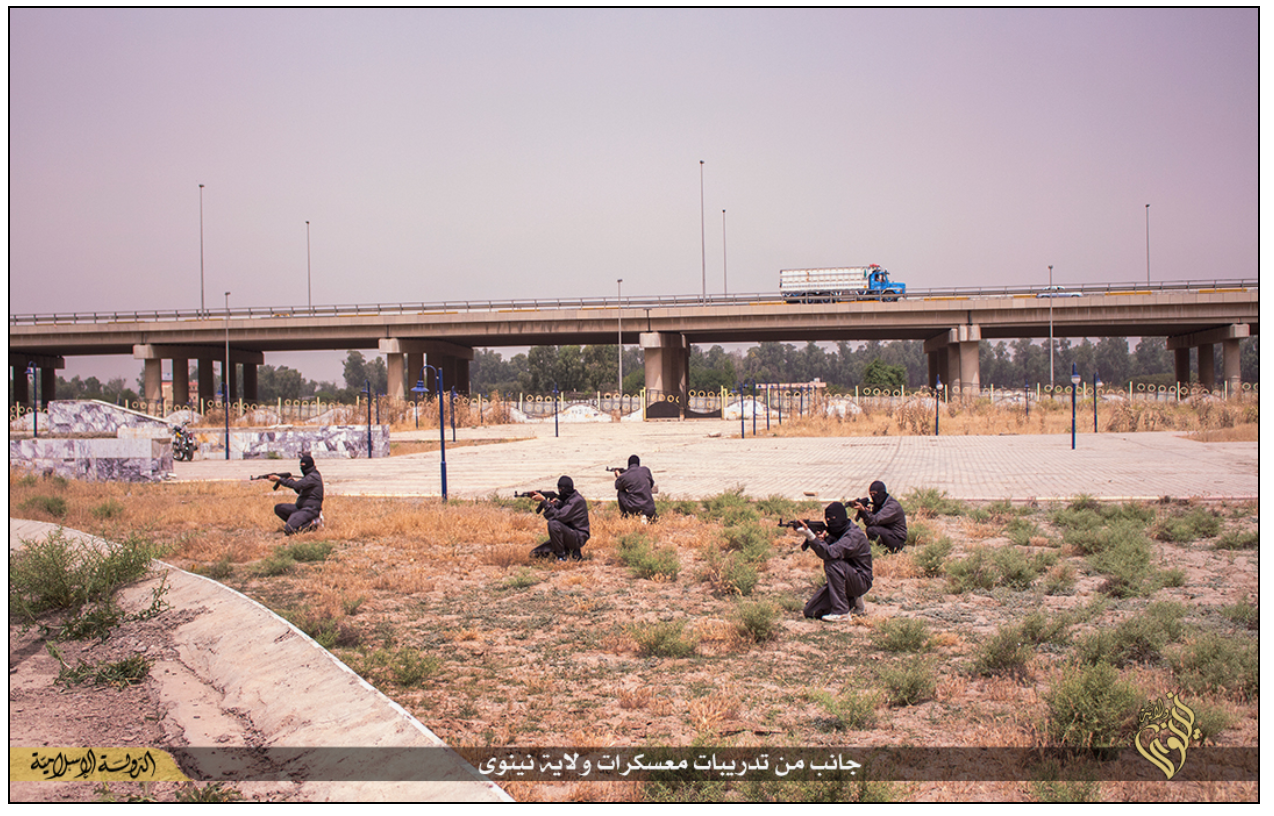

2. IS Releases Photographs From Nineveh Training Camp

- Source: Islamic State via Archive.li (Confirmed)

- Location: Mosul (Confirmed)

- Date: June 15, 2015 (Checking)

- Archived here

IS released a set of photographs in June 2015, which they said showed fighters training at a camp in Nineveh, Iraq. The photos show fighters using zip lines, rappelling, and posing with their weapons.

Source:

The photoset was being discussed online by IS-linked accounts, using the name جانب من تدريبات معسكرات ولاية نينوى or, “part of the training camps of Wilayat Nineveh.” Storyful used Google Search to search for the photos. They could be found on Archive Today.

IS content could be found simply by monitoring of conversations online and searching for the terms used.

An IS logo is on the lower left of each photo, and at the bottom of the page. It is the logo for a media organization based in IS’s Wilayat Nineveh, which is roughly equivalent to the Iraqi province of Nineveh.

Location:

The first photo shows the very distinctive Mosul Grand Mosque in the city.

Date:

The page is dated Shabaan 1436, which corresponds with May 20-June 17, 2015, on the Gregorian calendar. The photos were shared on June 15.

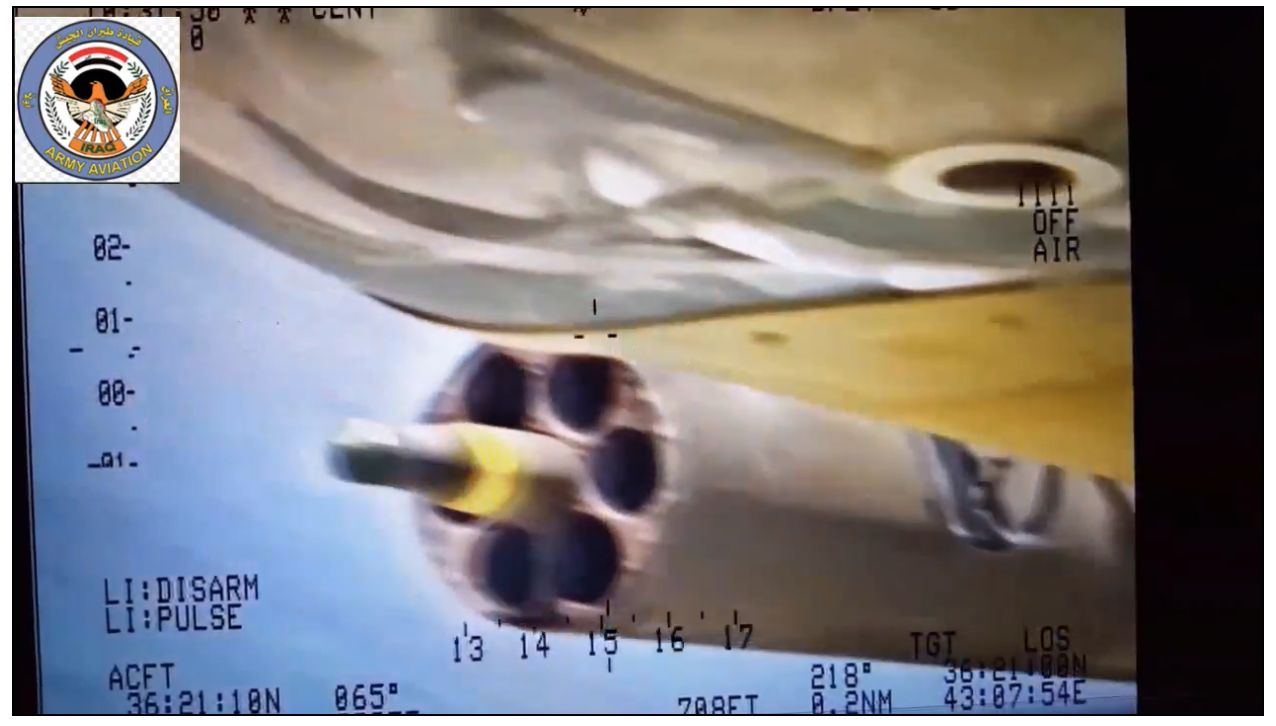

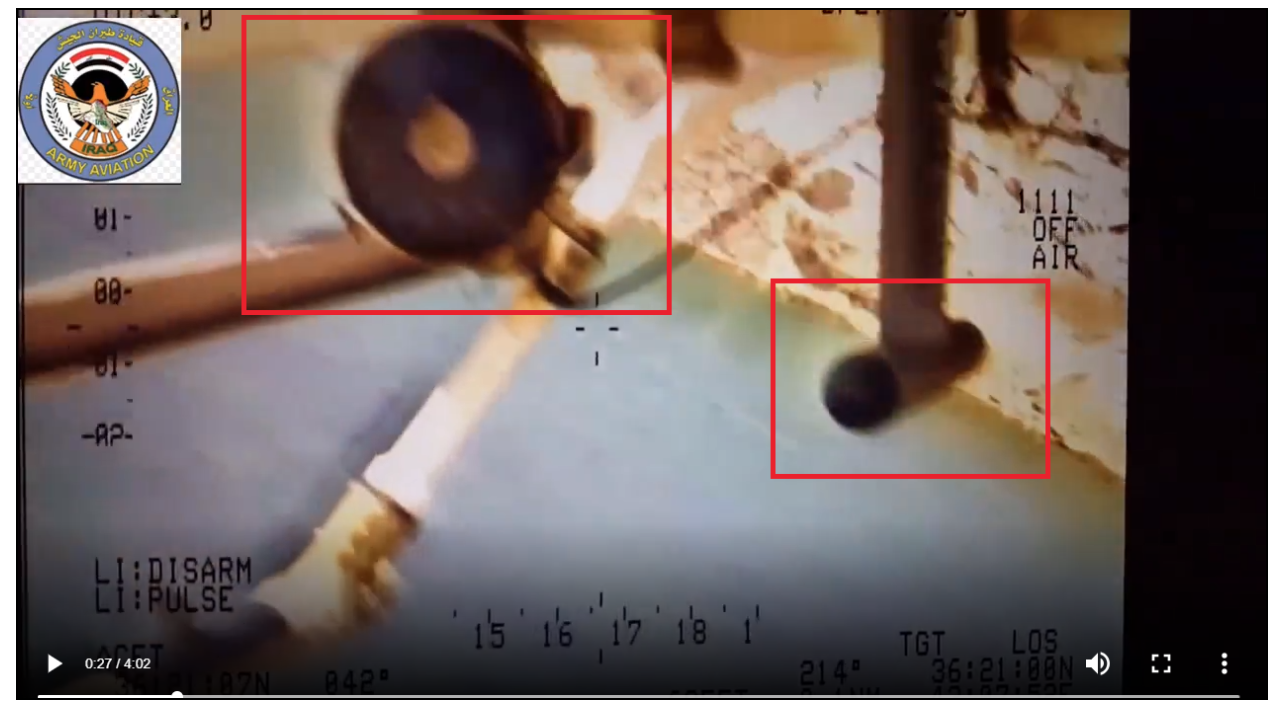

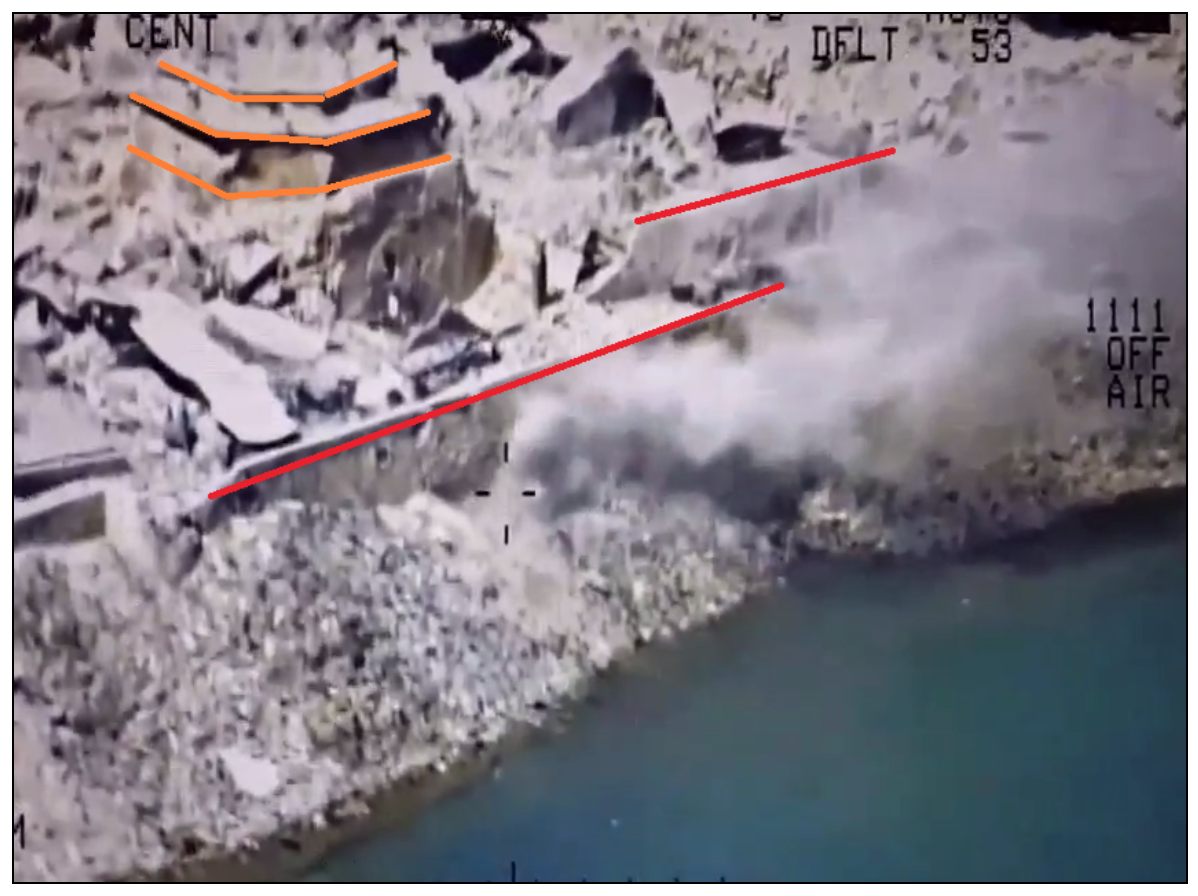

3. IS Fighters Showcase Weaponized Drone Amid Ongoing Battle for Mosul

- Source: Islamic State via Archive.org (Confirmed)

- Location: Mosul (Confirmed)

- Date: January 24, 2017 (Checking)

- Archived here

IS’s Wilayat Nineveh media organization released a propaganda video, titled Knights of the States, on January 24, 2017, showcasing a recently designed weaponized drone it said was being used against Iraqi forces.

The video’s release came just hours after Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi announced the capture of the western half of the city of Mosul, known as the Left Coast.

IS’s weaponization of drones was reported during the offensive to retake the city.

Source:

The video was released by IS’s Wilayat Nineveh media organization, which was based on Mosul. The video was uploaded to Archive.org and disseminated via IS-affiliated Telegram channels on January 24.

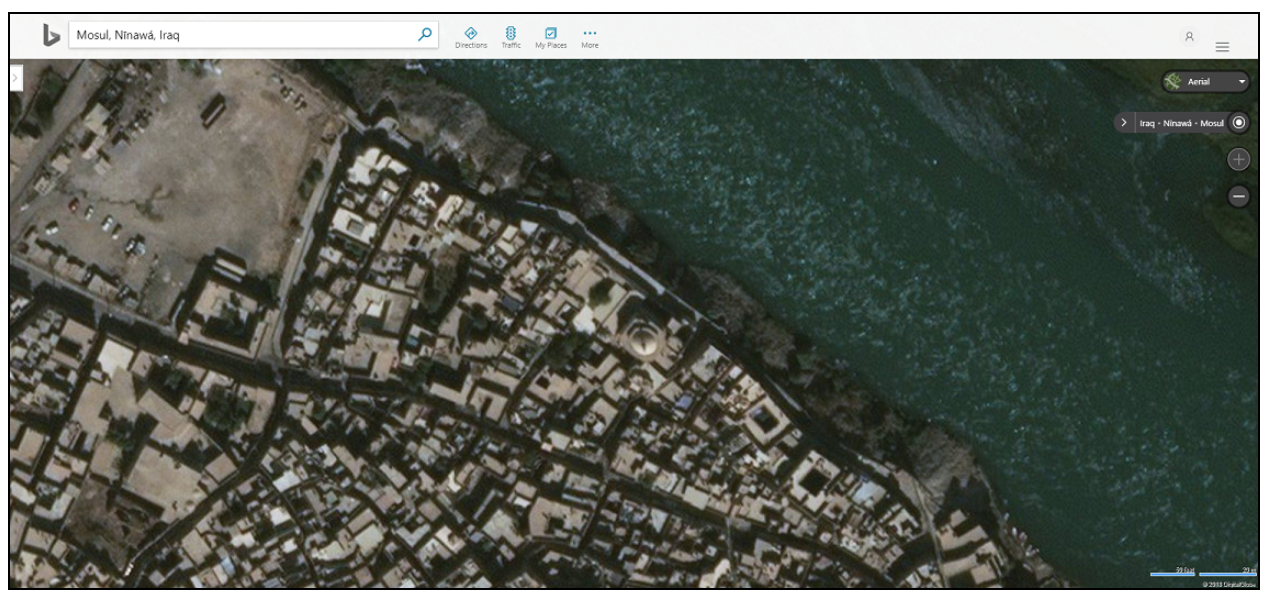

Location:

The Wilayat Nineveh media organization was headquartered in the city of Mosul. The first bridge, seen at the beginning of the video, tallies with a bridge seen on Google Maps. The second bridge seen is also located in Mosul and it tallies with Google Maps.

Date:

The video was uploaded to Archive.org and disseminated via IS-affiliated Telegram channels on January 24; however, it shows footage from a number of suicide bombing attacks inside the city of Mosul that took place throughout January 2017.

Ordinary Life Under IS Control

1. IS Return to Site of First Assault on the City for Propaganda Video

- Source: Islamic State via Archive.org (Confirmed)

- Location: Mosul (Confirmed)

- Date: November 28, 2014 (Corroborated)

- Archived here

The footage shows a busy city with traffic on the streets and people going about their business. A number of people are interviewed. The battle for Mosul is described, as well as details of life for residents under IS control. The video details the Sharia law courts in operation in the city.

Source:

Al-Hayat Media Center, an IS-affiliated media agency that specifically targeted westerners, released a video on November 28, 2014, that showed scenes from inside Mosul. IS militants captured the city in June after government forces abandoned their positions. Al-Hayat Media Center’s logo is shown at the start of the video and as a watermark throughout. The footage was shared via archive.org.

Location:

The location can be confirmed by comparison with Google Maps. The video was shot at a distinctive hotel in Mosul. See also Google Images. The hotel can be seen from 1:30 in the video.

The area surrounding the hotel is described in the video as where the assault on Mosul began. Storyful verified eyewitness video of the aftermath of the assault in June 2014, in which the hotel could be seen (archived here). The video shows distinctive lampposts, which tally with a photo shared on Google Images from the same street.

Date:

The earliest English-language reference to the video on Twitter was on November 28, 2014, on the now-suspended account @Shohdaa00 (this account was not archived at the time). The account had “Islamic Caliphate” in Arabic in its description. The account frequently posted about IS. The account can be retrieved on the Wayback Machine.

2. IS Opens Luxury Hotel in Mosul

- Source: Islamic State via justpaste.it (Confirmed)

- Location: Mosul (Confirmed)

- Date: May 2, 2015 (Corroborated)

- Archived here

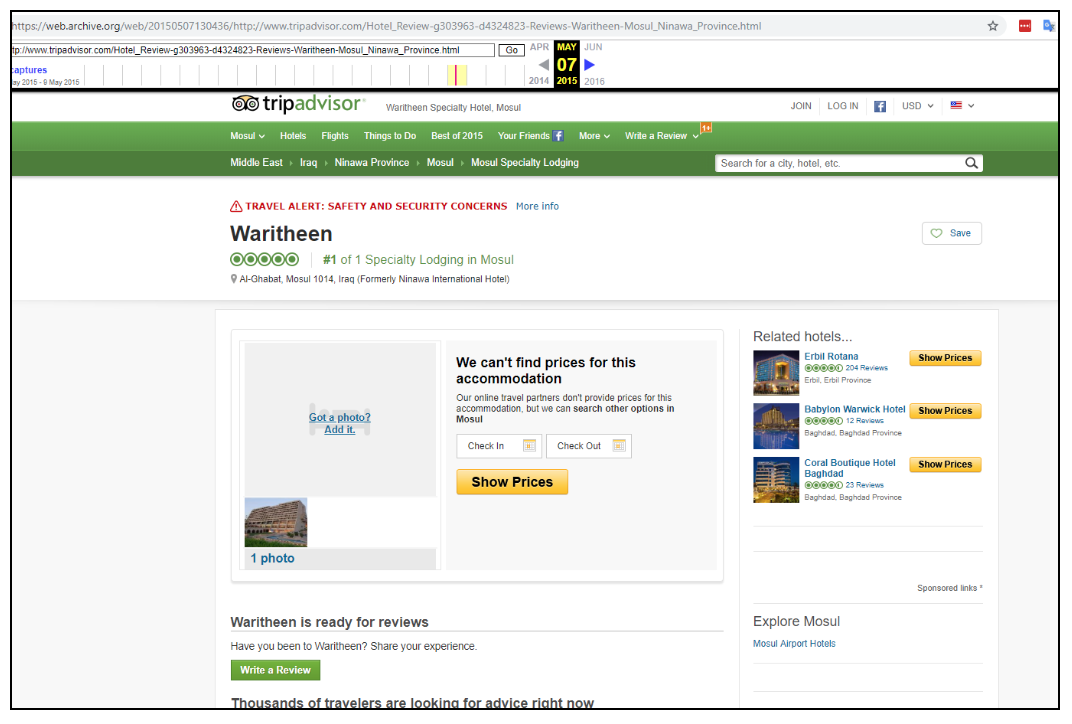

IS reopened the Nineveh International Hotel in Mosul at the beginning of May 2015, according to local activist reports. The hotel had previously been featured in propaganda footage released by the militant group. Storyful verified eyewitness footage of the aftermath of the assault in June 2014, in which the hotel could be seen (archived here).

The Wilayat Nineveh media organization released this photoset showing preparations for the grand reopening of the hotel, which IS renamed al-Warithein. The name was changed thus on a TripAdvisor listing.

Photos:

Source:

The photoset was released on justpaste.it by the Wilayat Nineveh media organization. This method was commonly used by IS for disseminating propaganda photos from Mosul. The photoset was shared widely on social media on May 4, 2015, by IS-affiliated accounts. The insignia tallies with that featured on other propaganda released by the Nineveh branch of IS.

Location:

The photoset was released by the regional media wing of the northern Iraqi province of Nineveh. The location can be confirmed by comparison with this geotagged image of the former Nineveh International Hotel in Mosul. The hotel has previously been featured in other propaganda released by IS.

Date:

The Wilayat Nineveh photoset appears to have been released by IS on May 4, 2015. The exact date on which the photos were taken is not known. They could have been taken as early as May 2, based on other photos shared on that date.

The Raqqa-based anti-IS activist group Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently shared a set of photos on May 2, described as being taken on the reopening of the Nineveh International Hotel by IS.

3. British Hostage John Cantlie Seen in IS Propaganda Video

- Source: Islamic State via Al-Hayat Media Centre (Confirmed)

- Location: Mosul (Confirmed)

- Date: Range – October, 2014, to January, 2015 (Confirmed)

- Archived here

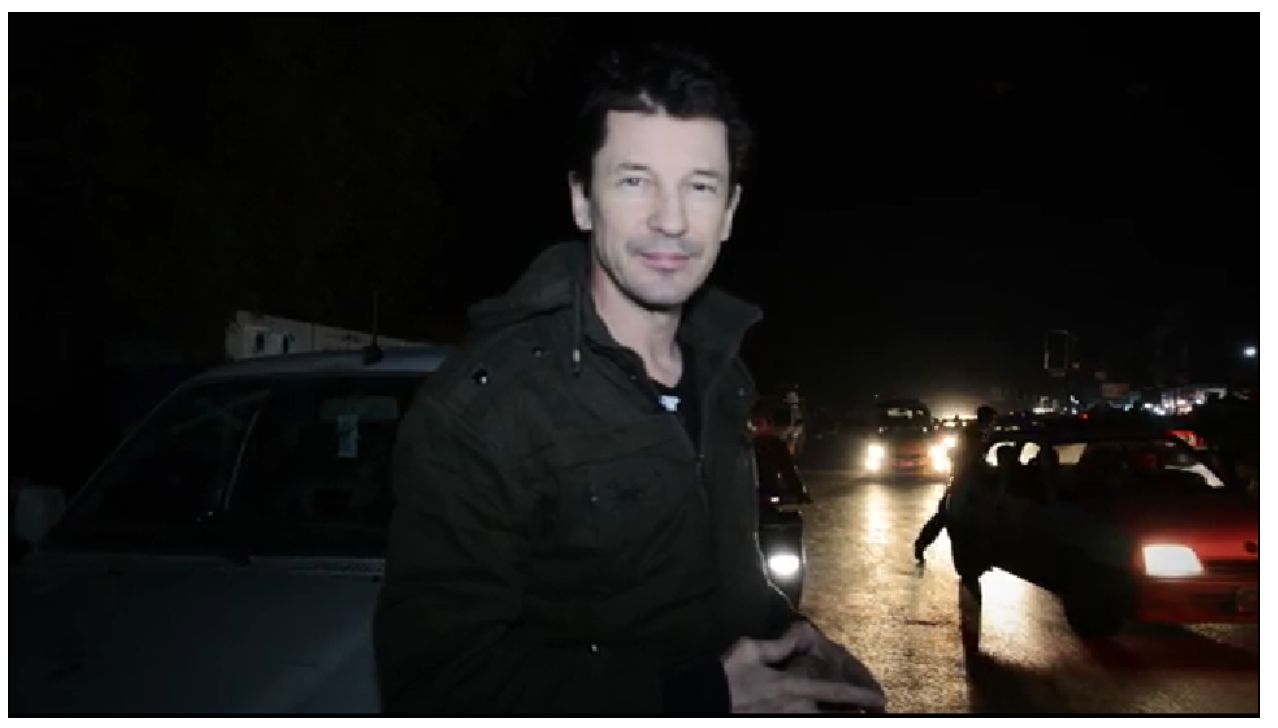

Al-Hayat Media Centre released a video on January 3, 2015, showing British hostage John Cantlie speaking in Mosul. Cantlie is a British journalist kidnapped in Syria in November 2012. This was the eighth propaganda video of Cantlie released by IS since his capture.

In this video, titled From Inside Mosul, Cantlie is described as being in the “bustling” city of Mosul, visiting children at a hospital, riding a motorbike on the city’s streets. He is seen shouting at a drone circling the city.

In his narration, Cantlie suggests that Western media reports of the situation in Mosul are incorrect. He says that prices have not gone up; that people have money to spend; that the electricity supply in the city had lasted “a lot longer than two hours in the last four days”.

Source:

The footage is marked with the Al-Hayat group’s logo. The link was widely circulated on Twitter and jihadist media forums on January 3, 2015. Note: these links were not archived at the time.

Location:

Cantlie appears at multiple locations in this video. The location of the souk (market) and hospital have not been independently confirmed. However, it was possible to confirm that Cantlie was in Mosul.

Storyful confirmed that Cantlie was at the Mashki Gate (5’34’’ in the video), a gate in Mosul’s ancient city walls, via this Wikipedia commons image. Note the street lights, the metal roofing atop the structure in the background, and the hill beyond it as seen in both the video and image. The video also shows the Old Bridge, which is a metal bridge that links Mosul’s Left and Right Banks.

This 2012 New York Times picture of the wall further corroborates the location.

Date: