Abstract

The renewed interest in the market as a unit of analysis has increased adoption of a market system dynamics (MSD) perspective. Since studies drawing on MSD have significant overlaps with other research traditions equally focused on market changes, we trace the theoretical boundaries of the literature on MSD, and unpack its evolution, in order to appreciate conceptual achievements and research directions. Building on change-process theorizing and on a reiterative processual multi-stage research strategy, we conduct a systematic review of the literature on MSD. We organize the findings into three stages of MSD’s maturation–infancy, adolescence, and adulthood–and show that MSD has grown into a market approach that is ever more multi-actor, theoretically-plural, and based on longitudinal methodologies. The existing literature has gradually shifted towards a balance in agency and structure in market change, and towards a more cautious view on the consumer’s role. Under-researched areas are pinpointed, along with research avenues that can further reinforce MSD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past two decades, marketing and consumer studies have seen a surge of interest in the market as the core unit of analysis (Araujo, 2007; Araujo et al., 2010; Kjellberg et al., 2012; Kjellberg & Murto, 2021; Mountford & Geiger, 2021). Proponents of constructivist market studies (CMS) (e.g., Fuentes and Sörum, 2019), theorists of the service dominant logic (SDL) (e.g., Vargo and Lusch, 2011), supporters of the systemic approach to marketing (e.g., Layton, 2019), and the community of macromarketers (e.g., DeQuero-Navarro et al., 2020) have to various extents all contributed to reintroducing the market to the main stage in marketing and consumer research. Equally animated by the desire to re-establish the central position of markets, a discipline subfield called ‘market system dynamics’ (henceforth MSD) has gained traction in the current literature.

Only recently formalized into a distinct approach (Giesler & Fischer, 2017), MSD has rapidly undergone a process of cultural and social legitimation–as testified by a specific ‘area of jurisdiction,’ a well-identified set of theoretical perspectives, a growing community of followers, an increasing number of journals publishing MSD research, and the existence of a sense of community based on the ‘consciousness of kind principle’ whereby MSD scholars identify themselves as belonging to the community, interact with each other and are familiar with each other’s work (Coskuner-Balli, 2013). Emblematic of this legitimation is the fact that the newly-released website of the Journal of Consumer Research suggests three papers–Dolbec and Fischer (2015); Humphreys, 2010b); Karababa and Ger (2011), all of them falling within the scope of MSD–as notable benchmarks and examples of inspiration for impactful consumer culture research.

MSD has been established as a theoretical perspective from which to describe markets as complex socio-cultural, political, and historical systems that stem from discursive negotiations and involve multiple market-shaping actors (Giesler & Fischer, 2017).

Rooted in social constructivism, the MSD perspective relies on an ontology that involves the framing of markets as social systems that contextualize a myriad of socio-cultural relationships (Giesler, 2003) which are constantly challenged by both inward and outward forces contributing to markets’ (temporal) stability or instability (Giesler, 2008; Mountford & Geiger, 2021).

Born with a focus on markets developing or transitioning toward novel configurations, MSD has emerged as an active response to scholars’ need to provide remedies for three main biases in the stream of marketing research with an interest in market phenomena. These biases are the excessive focus on the “hyper individualized, overly agentic, and ahistoric” inner world of consumers (‘micro level bias’) (Thompson et al., 2013, p. 151); overlooking the market role of actors other than consumers and firms (‘economic actor bias’); and the tendency to focus on variance, rather than historical and processual research questions (‘variance bias’) (Giesler & Fischer, 2017).

MSD has significant overlaps with other market-focused marketing paradigms (Kjellberg et al., 2012; Kjellberg & Murto, 2021), as well as with other research traditions likewise aimed at explaining how and why markets change, such as the sociology of markets (Fligstein & Dauter, 2007), category studies (Delmestri et al., 2020; Negro et al., 2010), and studies relying on socio-cognitive theories of market formation (Rosa et al., 1999). As such, identifying distinctive intellectual domains and goals of MSD is becoming increasingly problematic and, for this reason, needed. This is particularly urgent in light of two main shortcomings of the extant MSD literature. The first is the tendency of some scholars (e.g., Ertekin and Atik, 2020; Ogada and Lindberg, 2022; Ulver, 2019) to elevate MSD to the status of a theory rather than a broad theoretical perspective encompassing a multitude of theories. The second shortcoming, partially connected with the first, is the conflation of MSD with other highly popular sociological theories such as institutional and neo-institutional theory (Hartman & Coslor, 2019; Jafari et al., 2022; Slimane et al., 2019) or marketing and consumer studies’ approaches such as market shaping (Baker & Nenonen, 2020; Nenonen & Storbacka, 2021; Nenonen et al., 2021). This has led to an unclear theoretical positioning of MSD.

Indeed, we contend that remedying these shortcomings requires tracing the intellectual boundaries of MSD research and how these have changed and adapted overtime. In fact, the ability of a new field to challenge an established community and the logics whereby it creates knowledge (see Coskuner-Balli, 2013 for similar reflection on MSD’s cognate field of Consumer Culture Theory [henceforth CCT]) is the result of a longitudinal process that can only be unfolded by conducting a historical investigation of the challenging field (Augier et al., 2005; Tadajewski, 2006). Accordingly, unpacking the emergence of the MSD approach, and fully recognizing its merits, requires a historical reconstruction of how this field evolved, and reflection on whether and to what extent it has gained academic traction and legitimacy.

To address these points, the research reported in this paper aimed to answer the following research questions: What are the intellectual boundaries of the field known as MSD? How has the field evolved since its inception? How can MSD advance in the future?

Following the principles of process-theorizing (Giesler & Thompson, 2016), we paid attention to the field’s evolution by focusing on how the main tenets of MSD have been investigated over time, on the relative degree of agency that studies attribute to consumers, and on the type of change that is devised in MSD studies. The analysis pinpointed some under-researched areas that we discuss as more urgent to address, and that can inspire further work in the area.

Previous literature reviews on MSD

Despite its fairly recent inception, not only has MSD stimulated the emergence of a number of studies, but it has also attracted the interest of scholars who have attempted to summarize and discuss what has been achieved within the MSD tradition since its inception. Three reviews have been published to date, namely by Branstad and Solem (2020), Nøjgaard and Bajde (2021), and Jafari et al. (2022). Branstad and Solem (2020) provide a succinct overview of MSD research in order to summarize the thriving literature dealing with phenomena of consumer-driven market innovation, adoption, and diffusion. However, because the literature analyzed is limited to the sub-set of studies that focus on the dominant role of consumers in innovation, a large number of studies that focus on actors other than consumers are overlooked.

Nøjgaard and Bajde (2021) provide a critical analysis of the differences and similarities between MSD and CMS and examine the potential for cross-pollination between these two streams of market-focused research. Their work stands out because it draws stable conceptual boundaries between two distinct, but partly overlapping, market-oriented traditions in marketing research. However, Nøjgaard and Bajde (2021)’s aim is not to systematically reconstruct the whole lineage of the MSD body of knowledge but rather to pinpoint the key axiomatic distinctions between MSD and CMS, and to do so by focusing on a narrow set of seminal papers.

Finally, the analytical review by Jafari et al. (2022) attempts to classify MSD research in terms of Fourcade’s (2007) perspectives and Fligstein and Dauter’s (2007) five approaches to the study of markets. While this last review is noteworthy, it recategorizes the existing literature into five static silos, corresponding to as many approaches to the study of markets–namely network analysis, field analysis, performativity, political economy, and population ecology–thus overlooking temporal dynamics and tending to conflate MSD with neo-institutional theory, which is frequently used in MSD research. For this reason, Jafari et al. (2022)’s review includes studies that may have limited connections with this field of research.

In sum, although previous research provides some systematization and interpretation of MSD research, we still lack a comprehensive understanding of how this domain has evolved over time, and of where it is heading.

Methodology

Data collection

To provide a thorough and compelling overview of extant MSD studies, we adopted an emergent methodology that integrated principles of selective (Booth et al., 2016) and systematic (Tranfield et al., 2003) review with an inductive ontological analysis of the literature (Jones et al., 2011).

To identify relevant articles, we applied a processual, reiterative multi-stage strategy consisting of the three different consequential steps now described.

In the first step, we composed an initial sample of studies based on those identified as MSD research in the seminal editorial by Giesler and Fischer (2017), as well as in the three literature reviews mentioned above (Branstad & Solem, 2020; Jafari et al., 2022; Nøjgaard & Bajde, 2021). This process resulted in 34 publications after duplicates had been removed.

The second step involved adoption of a more systematic review approach to the literature, with an updating of our dataset to comprise the most recent publications in the field. Journal articles were retrieved from Web of Science (Clarivate) and Scopus (Elsevier). The search within these databases was performed by means of the query “market system dynamics” in all fields. Our initial search was performed in the Scopus database and led to identification of 120 articles. The same search was then performed on the Web of Science database. After merging the previously identified publications and removing all duplicates, we identified 123 articles. Two authors independently assessed the suitability of each of the 123 articles by carefully inspecting its title, abstract, and full text. Studies that mentioned “market system dynamics” but did not have any factual connection with MSD were discarded (93). The second step thus led to identification of 30 papers, which, merged with the results of the first step, led to a total of 64 publications in our dataset.

Finally, for further exhaustiveness of the review process, a manual search of selected journals was performed. The search was limited to seven top-tier marketing and consumer research journals in which the debate on MSD has been fertile in the past decade. These were: the Journal of Consumer Research, the Journal of Marketing, Marketing Theory, the Journal of Marketing Management, Consumption Markets & Culture, the Journal of Business Research, and the European Journal of Marketing. The manual selection resulted in the addition of seven articles, thus bringing the total number of publications to 71. After removing reviews and editorial papers, the bibliographic database retained for the analysis comprised a final number of 63 articles.

Data analysis

The categorization of the 63 articles retained for the analysis was conducted in two different ways. First, we resorted to Giesler and Fischer’s (2017) editorial identifying the key tenets of the MSD perspective, and indicating these tenets as hallmarks of MSD research.

The first key tenet is actor pluralism. MSD scholars acknowledge that markets and market-related phenomena are deeply embedded in complex social systems featuring the simultaneous presence of multiple actors. These multiple actors include, to name only some, the media (Humphreys, 2010a, b; Humphreys & Thompson, 2014), governments and policy makers (Brei & Tadajewski, 2015), religious authorities (Karababa & Ger, 2011), supra-firm institutions (Giesler & Veresiu, 2014), and opinion leaders (Parmentier & Fischer, 2015; Scaraboto & Fischer, 2013).

The second key tenet of MSD is theoretical pluralism. Because MSD is rooted in the same philosophical underpinnings as CCT, it should not be considered a ‘grand theory,’ but rather a research approach (Ertimur & Chen, 2020; Ertekin & Atik, 2020; Ertekin et al., 2020; Kertcher et al., 2020) open to a family of theories (Arnould & Thompson, 2005). In other words, MSD is a perspective which allows researchers to address the complexity of market systems and to achieve a balance between actors and structure (Fligstein & Dauter, 2007; Sewell, 1992) through the employment of different but mutually reinforcing theoretical lenses.

The third and last key tenet is the preference for longitudinal methodologies. Because MSD came to the fore to challenge marketing’s variance bias (Giesler & Fischer, 2017), studies belonging to this research strand should rely on longitudinal methodologies. This implies a generalized tendency of MSD scholars to reject an overly agentic, experiential, and phenomenological approach to data collection and analysis, and to adopt longitudinal techniques such as archival resources analysis (Diaz Ruiz & Makkar, 2021; Karababa & Ger, 2011), rich and extensive (n)ethnographies (Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Scaraboto & Fischer, 2013), and longitudinal panels (Press & Arnould, 2011; Ulver, 2019).

To be noted is that, although Giesler and Fischer (2017) cited these tenets as the distinctive hallmarks of MSD studies, they did not cogently recommend that they be necessarily respected in order for a piece of research to be included in the MSD field of studies. Rather, these tenets are evaluative criteria to be taken into account both when doing research on market dynamics and when evaluating the extent to which a study focused on market dynamics provides a solution for one or all of the three biases of consumer research which motivates the very existence of MSD.

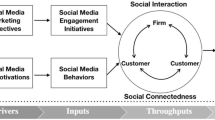

Once this first categorization of the literature had been conducted, we resorted to Giesler and Thompson’s (2016) tutorial on theorizing change in order to classify the publications identified into distinct clusters. The tutorial provides two main criteria with which to make sense of the MSD’s evolution over time. They are the degree of consumers’ enrollment in market dynamics, and the nature of change in markets and consumption systems (see Table 1). Although MSD scholars acknowledge that markets are a terrain of action by a wide array of actors (e.g., Brei and Tadajewski, 2015; Giesler and Veresiu, 2014; Humphreys, 2010a), the field’s coupling with CCT makes it naturally skewed toward consumers, and principally concerned to account for the role that consumers play in prompting, resisting or suffering market changes (e.g., Ertimur and Coskuner-Balli, 2015; Humphreys and Thompson, 2014; Kjeldgaard et al., 2017). The focus on consumers thus makes it possible to highlight both cases in which consumers provoke changes at the market level and those in which the market structure does not offer any or very limited space for their action.

Three different consumers’ enrollment styles are identified: (1) the consumer as an agent of change, i.e., triggering market changes, (2) the consumer as a subject of change, i.e., experiencing a shift with the force of change dynamics taking place in the market level, or (3) the consumer as a recursive subject, where consumers are both agents of change, and subject to the revised institutional conditions of the social realm in which they act.

Besides acknowledging different degrees of consumers’ agency, Giesler and Thompson’s (2016) tutorial was deemed suited to our aim of making sense of MSD’s evolution because it assumes that the notion of market change is not univocal, and that different types of change are possible.

Three types of change are in fact identified: transformative change, which implies that change is a process of adaptive responses to contextual demands and influences; topological change, which rests on the assumption that changes are triggered by field level conflicts involving actors vying for the same resources; and disruptive change, which, like topological change, involves the existence of conflicts, but especially consists of historical changes that are so disruptive to the marketplace that the latter experiences instability and unpredictability.

The intersection between consumers’ enrollment and the nature of change enabled us to allocate each study analyzed to one of nine genres of change, and to provide an original and non-immediate ‘snapshot’ of the research published to date.

The findings of this systematic approach to the literature are reported in the following sections, where a process-oriented contextualization of the MSD literature in three successive temporal phases is provided.

Results

A process-oriented review of MSD

Given that the research aim was to uncover hidden evolutionary patterns of the MSD field, the 63 papers identified were clustered into temporal frames. To identify these temporal frames, we followed a methodological approach inspired by historical research (Wadhwani & Bucheli, 2014). Accordingly, we first chronologically ordered the materials collected, i.e., papers classified as MSD-related. Then, we searched for events that produced patterns of change. In our case, these events corresponded to the publication of articles that pushed the field transitioning to the next level of maturation. Once the articles had been ordered and temporally bracketed, we engaged in an interpretive effort to understand how the field had evolved over time. This analytical procedure led to identification of three temporal timeframes, each signifying a different degree of the field’s maturation. We deemed the metaphor of ‘human development cycle’ (Elder & Shanahan, 2006) suitable to rhetorically describe the developmental trajectory that the field has followed since its inception, and for this reason named the three phases as infancy (2003–2011), adolescence (2012–2017) and adulthood (2018–2021).

Infancy grouped earlier studies on MSD. Adolescence was the phase during which the MSD literature started to acquire increasing consensus and growing legitimation as an autonomous stream of research. Finally, adulthood signified a phase in which the MSD field had gained ‘planful competence’ (Elder & Shanahan, 2006), i.e., had obtained a clear role within the broad field of consumer research and had precisely identified the goals it wanted to pursue. Each of the three phases is now described, with the reviewed journal articles being reported in Tables 2, 3 and 4 below.

The infancy of MSD (2003–2011)

Contributions published between 2003 and 2011 depict the infancy of the MSD approach (see Table 2). The timeframe begins in 2003, with Giesler’s positioning paper that evidenced the need for a system approach to markets and marketing that was lacking at the time; and it ends in 2011, the year before the Association for Consumer Research roundtable specifically devoted to MSD (Siebert & Thyroff, 2012). Giesler (2003) initiated a lively debate within the CCT community. Thereafter, scholars began to more seriously challenge their ontological posture, their epistemological position, and their methodological toolkit, with the never-ending dispute on agency and structure (Sewell, 1992). Consumer researchers realized that it was necessary to shift the focus from consumers’ lived experiences to the wider realms in which such lived experiences take place. The ensuing research culminated in Askegaard and Linnet’s (2011) seminal article. In their view, the way to achieve a substantive theoretical advance in consumer research was to accomplish a recursive dialogic regulation between the excessive individualism of early consumer studies and the structural determinism characterizing many sociological theories concerned with consumption. The reconciliation of these extreme poles could be achieved if the context of context, i.e., “the structuring force of such large-scale contexts, and the meaningful projects that arise in everyday sociality” (Askegaard & Linnet, 2011, p. 396) was accounted for. While the concept of markets as systems incepted by Giesler was only timidly proposed (Thompson & Coskuner-Balli, 2007), and a formalized agenda was lacking during MSD’s infancy, the first empirical studies employing this systemic approach started to be published.

MSD tenets

The findings emerging from the analysis of research published in this period are now discussed on the basis of perspectives on actor pluralism, theoretical pluralism, and longitudinal methodologies. When considering actors, initial studies adopted an agentic focus which was not limited to the traditional economic actors, i.e., producers and consumers. Exemplary of this inclusivity are the works by Humphreys (2010a, b), where the media, journalists and policy makers were considered as, and assumed to be, primary actors of market emergence and legitimation, and Sandikci and Ger’s (2010) study which gave religious movements and the media a primary role in explaining how the Islamic veil underwent a gradual process of popularization and acceptance.

As far as theories are concerned, it is clear that early MSD studies did not claim or try to establish the emerging systemic approach to markets as the ultimate grand theory explaining how markets work–which is the aim of market sociologists (Fligstein & Dauter, 2007). Rather, they relied on this approach as a perspective sufficiently broad to include several theories, such as co-optation theory, social utilitarianism, possessive individualism, institutional theory, stigma theory, Bourdieu’s theory of practice, Foucault’s theory of power, De Certeau’s theory of consumer resistance, and organizational identity theory (see Table 2).

Only a few studies (e.g., Karababa and Ger, 2011; Sandikci and Ger, 2010) were built on complex theoretical frameworks where multiple theories were used at the same time.

Finally, with regard to the methodologies used, scholars began to approach contexts with longitudinal analysis, and combined multiple methods into a single program of inquiry, through phenomenological in-depth interviews, ethnographies, participant and nonparticipant observation, historical narratives, and content-analysis (Giesler, 2008; Humphreys, 2010a, b; Sandikci & Ger, 2010; Thompson & Coskuner-Balli, 2007), as well as the use of secondary data such as historical sources (Karababa & Ger, 2011). However, the influences of more traditional CCT traditions were still present, with a number of studies resorting to single-method, purely interpretivist, research designs (e.g., Peñaloza and Barnhart, 2011; Press and Arnould, 2011).

Change theorizing

A common feature of the research published in this phase was a markedly socio-cognitive and micro-constructivist conceptualization of markets, where discursive frames and ideologies were considered to be central in the process through which market systems form and change (Fligstein, 1996). The majority of the studies published during MSD’s infancy were in fact characterized by topological change (i.e., change produced by field-level conflicts) or by a disruptive approach to change (i.e., produced by conflicts where no stability is achieved) (Table 1).

This was apparent in Thompson and Coskuner-Balli’s (2007) exploration of countervailing markets, where markets were described as social systems that amplify, implement and promote countercultural principles, meanings, and ideals. Focusing on the emergence and subsequent institutionalization of the gambling industry, Humphreys (2010a, b) still placed conflicts in the foreground, but viewed this framing as unsuitable for analyzing the market phenomenon. Accordingly, and consistently with the view of markets as socio-cognitive structures (Rosa et al., 1999), markets were supposed to be in flux so that a common understanding and shared meaning around both values and motives of market exchange could be reached. In her research, Humphreys (2010a, b) showed that the possibility for casino gambling to gain legitimacy depended upon the market’s ability to achieve consensus around a common frame, through which casino gambling could be seen, interpreted and legitimized.

A disruptive-like type of change was instead discussed in the case of the emergence and rise of music downloading (Giesler, 2008), and in the study on the formation of Ottoman coffeehouse culture (Karababa & Ger, 2011). In the former case, markets were conceived as ideological battlegrounds, as stages on which dramas take place, and where institutional instability is recursive and ceaseless. In the latter case, the Ottoman coffeehouse culture and its respective market were found to be constantly triggered by irreconcilable tensions between the Ottoman man’s pursuit of pleasure and his religious morality.

On the other hand, Sandikci and Ger (2010) and Press and Arnould (2011) viewed change in transformative terms. More specifically, Sandikci and Ger (2010) showed how Islam veiling shifted from being interpreted as deviant to being considered a fashionable practice through a gradual process of adaptation to contextual demands and influences. A similar phenomenon of gradual market adaptation was also revealed by Press and Arnould (2011), who found how constituents come to identify with communities (i.e., community-supported agriculture) and organizations (i.e., an advertising agency).

When considering consumers’ enrollment in theorizing change, studies published during MSD’s infancy had a general tendency to downplay the agentic role of consumers. In fact, consumers were considered subjects of change (Humphreys, 2010a, b; Press & Arnould, 2011), or recursive subjects of change (Giesler, 2008; Karababa & Ger, 2011; Peñaloza & Barnhart, 2011; Sandikci & Ger, 2010; Thompson & Coskuner-Balli, 2007), while no study explicitly or clearly represented consumers as actors of change.

The adolescence of MSD (2012–2017)

The adolescence of MSD began with an Association for Consumer Research roundtable aimed at discussing the “value and the open questions” of the nascent body of research (Siebert & Thyroff, 2012), and culminated with the actual formalization of MSD in the Marketing Theory opening editorial of its 2017 special issue (Giesler & Fischer, 2017) (Table 3). Adolescence was the stage in which the MSD approach started gaining academic traction. The emergent stream of research was generated by a conspicuous number of studies by a notable group of scholars, spanning heterogenous research contexts and theoretical avenues, and published in top-tier outlets such as the Journal of Consumer Research (7 papers), the Journal of Marketing (3), Marketing Theory (5), the European Journal of Marketing (2), and the Journal of Marketing Management (1).

A bird’s eye view of the literature published during MSD’s adolescence suggests grouping studies issued in that period into two distinct clusters.

The first cluster consists of studies aimed at understanding phenomena of market (de)legitimation. Inspired by the works of Humphreys (2010a, b) and leaning towards a socio-cognitive view of market formation (Rosa et al., 1999), these studies viewed legitimation as a phenomenon occurring when relevant institutional actors have a convergent (i.e., when legitimacy is achieved) or divergent (i.e., when legitimacy is not achieved) view about what a market, market category, or a market practice stands for. Specifically, analysis reveals that all the studies clustered in this group focused on markets or market-related phenomena that suffer from illegitimacy, or that are not fully legitimized when they first appear or are first established.

The second cluster groups studies focus on consumer-driven market dynamics, i.e., consumers’ individual or collective, intentional or unintentional actions that have the power to generate significant changes in extant market structures, or to spark the emergence of new ones. Although these dynamics were not necessarily without conflicts (Dolbec & Fischer, 2015; Kjeldgaard et al., 2017), the conflictual stance of consumers is often viewed as a generative rather than a dismantling force. As Martin and Schouten (2014) stressed, market dynamics are not necessarily conflictual, and do not necessarily imply that consumers have an antagonistic attitude toward the established market structure. Rather, consumers can provide support for existing logics, or they can drive the formation of a new market within and in harmony with an existing field, when incumbents are not able to provide solutions to untapped needs.

Acknowledgement that market dynamics are not always conflictual led scholars to balance their view of markets as being both sites of contention and competition, as well as of mutuality and collaboration (Kjeldgaard et al., 2017). At the same time, perhaps thanks to this shift in perspective, MSD research expanded its domain to include less idiosyncratic markets such as plastic-bottled water (Brei & Tadajewski, 2015), oil (Finch et al., 2017; Humphreys & Thompson, 2014), beer (Kjeldgaard et al., 2017), and agriculture (Press et al., 2014).

MSD tenets

The adolescence of MSD further expanded the array of market actors considered. For example, Giesler and Veresiu (2014) conducted a pioneering investigation of the role of supra-national market actors such as the World Economic Forum (WEF). They longitudinally analyzed the initiatives that the organization performed over a period of nine years to co-create multiple forms of responsible consumers. Similarly, Coskuner-Balli and Tumbat (2017) assessed 30 years of Presidential speeches about the institution of free-trade in the US, to investigate the rhetorical role that the government, a typically overlooked market actor, played in the development and maintenance of macro-market institutions. However, despite a few exceptions (Brei & Tadajewski, 2015; Dolbec & Fischer, 2015; Finch et al., 2017; Hietanen & Rokka, 2015), articles published during this stage still tended to focus on a small set of predominant market-shaping actors, failing to really adopt a multi-actor approach whereby a wide array of market actors and their respective influences were investigated at the same time.

Theoretically, studies published during MSD’s adolescence evidence a growth in the usage of the tenets of the institutional logic perspective (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008; Thornton et al., 2015). Logics were analyzed in different bracketing units, including media discourses, consumers practices, brand narratives, and firm strategies (Coskuner-Balli & Ertimur, 2016; Ertimur & Coskuner-Balli, 2015; Humphreys & Thompson, 2014; Wilner & Huff, 2016).

It is worth noting, however, that studies published during this stage rarely resorted to institutional logics alone. Institutional logics were used alongside other theories such as Bourdieu’s social field theory (Dolbec & Fischer, 2015; Scaraboto & Fischer, 2013), Holt’s (2004) cultural branding paradigm (Humphreys & Thompson, 2014), and Carroll’s (1985) resource partitioning theory (Ertimur & Coskuner-Balli, 2015). Although the neo-institutional approach to the study of market dynamics took off during MSD’s adolescence, some studies also stand out for eclectically resorting to different theories. For example, the exploration of the Danish beer market by Kjeldgaard et al. (2017) employed Strategic Action Field theory (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012), a social theory which condenses principles of institutional and social movement theory into a unique theoretical lens. Others instead opted to approach markets and their dynamics through the lenses of Actor-Network Theory (Giesler, 2012; Martin & Schouten, 2014), and shared a view of the market as an actor able to demonstrate agency. As Martin and Schouten (2014) acutely argued, markets are not endowed with supply chains, marketers and consumers; markets co-create all these components. Shifting the focus away from the notion of markets as institutions, studies grounded on the tenets of ANT investigated markets as both performative entities and stages, characterized by socio-material relations among a plethora of market-shaping actors.

Methodologically, studies published during MSD’s adolescence were often based on increasingly complex methodological designs with multiple methods used jointly, like qualitative and automated content analysis (Coskuner-Balli & Tumbat, 2017; Giesler, 2012; Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Humphreys & Thompson, 2014; Wilner & Huff, 2016), ethnography and netnography, or used as single methodologies (Coskuner-Balli & Ertimur, 2016; Scaraboto & Fischer, 2013; Vikas et al., 2015), or combined with other instruments such as interviews, archival data, and historical narratives (Dolbec & Fischer, 2015; Ertimur & Coskuner-Balli, 2015; Hietanen & Rokka, 2015; Martin & Schouten, 2014; Parmentier & Fischer, 2015).

Change theorizing

A specific feature of the literature published in the adolescence phase, and which distinguishes it from the previous stage, is that studies shedding light on market dynamics were not necessarily related to market formation and change. For example, Humphreys and Thompson (2014), Press et al. (2014) and Coskuner-Balli and Tumbat (2017) investigated the phenomenon of stability, while Parmentier and Fischer (2015) examined a particular phenomenon of change, namely decline (or dissipation).

Thus, similar to what occurred in the field’s infancy, MSD’s adolescence was also characterized by a significant prevalence of research framing change in disruptive and topological terms. Scholars seemed to have a preference for the investigation of contexts in which the magnitude of change was significant, while research focusing on incremental transformation was in more limited supply.

Similarly to the previous phase, as far as consumers’ enrollment is concerned, the field’s adolescence presented less agentic views of consumers as drivers of market changes, and rather described consumers either in a recursive position (Brei & Tadajewski, 2015; Coskuner-Balli & Ertimur, 2016; Ertimur & Coskuner-Balli, 2015; Giesler, 2012; Hietanen & Rokka, 2015; Press et al., 2014; Vikas et al., 2015), or as subjects of change (Coskuner-Balli & Tumbat, 2017; Finch et al., 2017; Giesler & Veresiu, 2014; Humphreys & Thompson, 2014; Wilner & Huff, 2016). As such, a greater role was assigned to the structured context in which consumers are nested.

For example, a somewhat passive view of consumers was held by Humphreys and Thompson (2014), who framed them as recipients of brand-centric narratives attempting to re-establish consumers’ trust in a firm, following a brand crisis such as a natural disaster caused by a petrol company. Similarly, Giesler and Veresiu (2014) purposefully opposed the conventional wisdom of responsible consumption as a consumer choice, and relied on viewing responsible consumption as a response triggered by the active creation and management of consumers as moral subjects by supra-national powerful organizations. Again, a similar way to frame consumers’ enrollment in market change is apparent in the study by Wilner and Huff (2016), who associated the spread and legitimation of sex toys with this product category’s transition toward more creative product designs. Coskuner-Balli and Tumbat (2017)’s article explained the emergence and spread of free trade as a political project where consumers were left no space; and in the aforementioned research by Finch et al. (2017) consumers were not even considered in the activities of regulating, developing and exchanging the green chemistry market.

Beyond these studies, however, MSD research started giving more room to consumers as agents of change. This was apparent in Scaraboto and Fischer (2013) and Dolbec and Fischer (2015)’s studies, where the role of overweight consumers seeking greater inclusion in the mainstream market and the role of fashion bloggers as arbiters of taste were respectively examined to make sense of drastic changes in the fashion market. Martin and Schouten (2014) also attributed significant agency to consumers in their study on the emergence of the minimoto market, as did Parmentier and Fischer (2015) in their investigation of the decline of America’s Next Top Model, Kjeldgaard et al. (2017), who focused on organized enthusiast consumers as (re)shapers of the Danish beer market, and Kjellberg and Olson (2017), who assigned consumers a primary role in creating the conditions for the cannabis market to emerge and grow. It is interesting to note that when consumers were framed as agents of change, studies tended to approach change as a transformative dynamic. Thus, although scholars increasingly viewed consumers as actors able to trigger changes in market structures, they implicitly assumed that these changes were of less magnitude than in other situations in which the consumers’ role is marginal or recursive.

The adulthood of MSD (2018–2021)

The formalization of MSD as an autonomous stream of research (Giesler & Fischer, 2017) led to this approach becoming popular. The inception of a novel “academic brand” (Coskuner-Balli, 2013) provided the opportunity for this research stream to expand its institutional borders. From 2018 onward (Table 4), MSD-based papers also started appearing in other outlets, such as the Journal of Business Research (9 papers), the Journal of Macromarketing (5), Industrial Marketing Management (3), the Journal of Marketing Management (3), Consumption, Markets & Culture (2), and the International Journal of Research in Marketing (1).

The spread of MSD across the marketing discipline initiated the adulthood of this field of studies. During the field’s adulthood, scholars started making efforts to understand dynamics that had hitherto been less explored, such as the stability/instability of mature markets (Debenedetti et al., 2020; Ertekin et al., 2020), the formation of transient market configurations (Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018), the inception of highly complex product categories (Kertcher et al., 2020), maintenance (Philippe et al., 2022), fragmentation (Mimoun et al., 2022), adaptation and revival (Ertimur & Chen, 2020; Regany et al., 2021), and market decline (Baker et al., 2018; Valor et al., 2021).

To be noted is that, during its adulthood, MSD’s terminology began to be used together with that of other approaches and traditions similarly focused on market dynamics, like co-creation (Ertimur & Chen, 2020; Kertcher et al., 2020), macromarketing (Ertekin & Atik, 2020; Ulver, 2019; Wiebe & Mitchell, 2022), constructivism (Smaniotto et al., 2021), market-shaping (Baker et al., 2018; Kullak et al., 2022; Yngfalk & Yngfalk, 2020) and market-driving (Humphreys & Carpenter, 2018; Maciel & Fischer, 2020). For example, Kertcher et al. (2020) blended MSD with co-creation to advance the current understanding of how a complex technological innovation like grid computing can spread. Similarly, Ertekin and Atik (2020) combined MSD with the macromarketing tradition to investigate how a logic guided by sustainability became dominant in the fashion market.

The adulthood of MSD has recently also been marked by a slight change in the conceptualization of markets. Despite being still largely conceived in terms of linguistic and semiotic relationality (Bajde et al., 2022; Coskuner-Balli et al., 2021; Middleton & Turnbull, 2021), it is especially during this phase that markets have begun to be considered socio-material and political plastic entities (Nenonen et al., 2014), open to manipulation by the plethora of human and non-human actors that voluntarily or unintentionally participate in the process of market dynamics (Baker et al., 2018; Ertekin et al., 2020; Huff et al., 2021; Kertcher et al., 2020; Schöps et al., 2022). For example, in their analysis of the legitimation of the US cannabis market, Huff et al. (2021) framed this contested market with an assemblage lens (Çalışkan & Callon, 2010; Deleuze & Guattari, 1987) and provided a view of the market comprising multiple assemblage layers embedded in each other. These layers involve also a product-level assemblage to emphasize the role that materiality plays in creating the conditions for new markets to emerge and thrive and for new market meanings to be established. This object-oriented conceptualization of the market has required broadening the array of marketplace actors by including objects in a way similar neo-institutional theorists did with the introduction of the core idea of institutional objects (Friedland, 2018) to emphasize that material artifacts embody the social realm in which they are created and made meaningful (Jones et al., 2017).

MSD tenets

During MSD’s adulthood, studies have shifted toward a more holistic approach (Ertekin & Atik, 2020), and become more markedly multi-actor, i.e., more sensitive to including and gauging the interventions and contributions of a broader set of market actors that may lead to market dynamism. For example, Baker et al. (2018) investigated the dynamics of change in the circus market and focused on a broad array of actors including circus owners and troupes, governments, and legislators, supporting associations, street artists, activists, and circus schools, as relevant categories of actors that led to changing the status quo. Humphreys and Carpenter (2018) included distributors, retailers, critics, producers and consumers, to explain how American wine makers were able to shape consumers’ preferences to their own advantage. Ertimur and Chen (2020) examined the role of institutional actors such as academics, healthcare professionals, bloggers, and producers, in the adaptation, renovation, and spread of an already-existing nutritional practice, the Paleolithic diet. Ertekin and Atik (2020) investigated how sustainability was revolutionizing the fashion industry through the joint participation of designers, retailers, luxury brands, fashion associations, and consumers. Regany et al. (2021) cast light on the neglected configuration where both legitimizing and delegitimizing pressures are exercised in the same market by the institutional work of consumers, policy makers, researchers, craftsmen, designers, manufacturers, sellers and suppliers. Along these lines, Bajde et al.’s (2022) study on the evolution of the microfinance industry similarly accounted for the role that multiple audiences, e.g., experts, celebrities, politicians, commentators, industry members, industry-wide associations, governmental institutions, and NGOs, play in shaping the public discourse surrounding an industry.

The literature published since 2018 onward also features a shift of interest from powerful to less powerful market actors such as immigrants (Veresiu & Giesler, 2018), small producers (Baker & Nenonen, 2020), and oppressed social activists (Ghaffari et al., 2019), who were little considered but could foster market change(s) through their purposeful work in overcoming market restrictions and barriers. It is also worth noting that the literature published during the MSD’s adulthood has not only expanded its scope of analysis by including a wider array of actors; it has also improved the MSD tradition in terms of ontological quality, because research started to more seriously acknowledge the influence of space and materiality in the market system (Huff et al., 2021; Smaniotto et al., 2021). In fact, from 2018 onward, it was increasingly recognized that objects do not merely populate markets, but are able to shape the context in which they are embedded, with their own reflexive agency. For example, by combining MSD with constructivist thinking, Smaniotto et al. (2021) postulated that consumption logistics, i.e., “the system of interrelated practices ordering the heterogeneous entities of consumption in space and time” (p. 9), is not to be viewed as a mere practical process of market organization, but as a complex system of both practical and symbolic practices which creates the conditions for markets to exist. Corroborating the importance of accounting for objects’ materiality in the investigation of market dynamics, the study by Huff et al. (2021) on the US cannabis market found that the legitimation process of a product passes through its expressive capacities, allowing consumers to make sense of the product itself, for instance by comparing it with other existing products. Through performances of sensory (mis)alignments, objects manifest their political expressive capacities and manage to establish the cultural meanings that are necessary for a category to be accepted.

When considering the theoretical approaches being used, the MSD field’s adulthood is also visible in the gradual alignment of research with sociological theories suited to explaining how complex systems like markets can evolve and change.

A growing number of studies started to employ the actor-oriented tenet of neo-institutional theory, i.e., institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006), to analyze market-related phenomena (Baker et al., 2018; Coskuner-Balli et al., 2021; Ertekin & Atik, 2020; Ghaffari et al., 2019; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Kullak et al., 2022; Wiebe & Mitchell, 2022; Yngfalk & Yngfalk, 2020).

By entailing the purposive action of individuals and organizations to create, maintain, and disrupt institutions (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006), institutional work reorients institutional thinking toward actors who are able to create institutions via heterogenous forms of work aimed at changing the shared cognitive, meaning or belief systems underpinning institutions, or exerting a political influence on them (Gawer & Phillips, 2013). MSD research has properly accounted for these various forms of institutional work, and the effects and dynamics that they trigger across different market configurations. For example, Coskuner-Balli et al. (2021) documented how, in the contested cannabis market, the pioneer brand Madmen managed to navigate the intrinsic complexity of the field by means of acquiring and redistributing field-configuring resources, and copying what other actors do in parallel fields, eventually promoting the formation of new consumers’ identities. In a similar vein, Regany et al. (2021) outlined that the dominant emancipatory movement which led to delegitimating the safsari is instantiated via works of dissociation and disconnection, whilst the dominated traditionalist logic, which tries to revamp the contested product, presents processes of nostalgic reconstruction, preservation of cultural heritage and local identity, and adaptation of utilitarian convenience. Furthermore, Ertimur and Chen (2020) found that three main groups of actors, namely academics, healthcare professionals, and market agents such as bloggers, entrepreneurs, and producers, were all engaged in the process of theorizing, mythologizing, and customizing the paleo diet to renovate this product category.

Methodologically speaking, despite an evident increase in the richness of the data gathered and analytical approaches, the adulthood stage displays a tendency, on the one hand, to privilege traditional CCT methods such as (n)ethnography and phenomenological approaches, and on the other, to embark on longitudinal analyses with limited time spans (e.g., few months), and thus not inherently historical. Although the latter is not a drawback per se, these tendencies are somehow misaligned with the MSD approach, and promise to overcome the microlevel and variance biases characterizing consumer research. For example, Gollnhofer and Kuruoglu’s (2018) exploration of makeshift markets, Debenedetti et al.’s (2020) analysis of legitimacy maintenance in French automotive industry, and Coskuner-Balli et al.’s (2021) investigation of cannabis market covered a period of two years; similarly, Hartman and Coslor’s (2019) analysis of the egg donor market, and Thompson-Whiteside and Turnbull’s (2021) exploration of the French advertising industry covered a period of approximately twelve months.

Change theorizing

Compared to MSD’s infancy and adolescence, the number of studies focusing on transformative market dynamics has significantly grown during the field’s adulthood (see Baker and Nenonen, 2020; Baker et al., 2018; Biraghi et al., 2018; Diaz Ruiz and Makkar, 2021; Ertimur and Chen, 2020; Humphreys and Carpenter, 2018; Kertcher et al., 2020; Kullak et al., 2022; Maciel and Fischer, 2020; Nguyen and Özçaglar-Toulouse, 2021; Ulver, 2019; Collet and Rémy, 2022; Ogada and Lindberg, 2022; Valor et al., 2021). Thus, it is not surprising that consumers’ enrollment in such dynamics of change is restrained, because consumers are very rarely considered by scholars as actors of change able to drive market transformations. The only exceptions are Ulver (2019), Maciel and Fischer (2020), Diaz Ruiz and Makkar (2021), and Valor et al. (2021) who respectively studied the emergence of the foodie culture, of craft breweries, of board sports, and the ideological fight against the bullfighting industry. Despite dealing with different market categories, these studies were similar in their view of consumers as key initiators of market shifts, which naturally granted them wider room for action and influence. The only two studies that framed consumers as actors of change, and that concentrated on disruptive market dynamics were both focused on the food market (Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Gollnhofer et al., 2019) and emphasized the ideological battles underlying a market that is increasingly perceived as unfair and fraught with contradictions.

A large number of studies published from 2018 onward instead framed consumers’ enrollment in market dynamics in recursive terms (Baker et al., 2018; Biraghi et al., 2018; Collet & Rémy, 2022; Coskuner-Balli et al., 2021; Ertekin & Atik, 2020; Ghaffari et al., 2019; Huff et al., 2021; Kertcher et al., 2020; Middleton & Turnbull, 2021; Mimoun et al., 2022; Regany et al., 2021; Ogada & Lindberg, 2022; Thompson-Whiteside & Turnbull, 2021; Veresiu & Giesler, 2018; Weijo et al., 2018; Wiart et al., 2022). That is, they assumed that consumers are both active influencers of market transformation and passive spectators of dynamics of change that do not necessarily fall under their control and within their sphere of action. As such, the majority of these studies were theoretically grounded on the tenets of institutional theory and on its refinement with institutional logics and institutional work (see Baker et al., 2018; Coskuner-Balli et al., 2021; Ertekin and Atik, 2020; Ghaffari et al., 2019; Middleton and Turnbull, 2021; Regany et al., 2021; Thompson-Whiteside and Turnbull, 2021).

Discussion and conclusion

The above examination of the literature first identified if and to what extent the three tenets of actor pluralism, theoretical pluralism, and longitudinal methodologies (Giesler & Fischer, 2017) have been implemented in MSD oriented studies. Then it identified three main temporal phases corresponding to as many stages of the field’s maturation–and for this reason named them ‘infancy,’ ‘adolescence,’ and ‘adulthood.’ Each stage does not only represent a gradual emancipation of the field; it also makes it possible to infer a gradual process of MSD’s academic legitimation (Coskuner-Balli, 2013).

Moreover, the application of Giesler and Thompson’s (2016) tutorial has made it possible to identify a tendency of MSD research to constantly fluctuate between an approach to market dynamics in which consumers are bestowed with the primary role as actors of change, and another one in which consumers’ transformative power is downplayed while the institutionalized and resilient nature of the structural conditions that characterize markets is acknowledged.

The results of our literature analysis enabled us to devise developmental trajectories for the field that we deem overriding to advance MSD and its agenda. These trajectories primarily concern theories and theoretical approaches, the number and nature of actors involved in studies, the type of market dynamics and research contexts considered and, finally, research methodologies and methods that can be potentially applied.

Regarding theories and theoretical approaches, our analysis made it possible to highlight the gradual transition of MSD toward an ontological and epistemological position more symmetrical with other streams of studies equally focused on market change. It seems that the more scholars look at market dynamics in a holistic fashion (i.e., including a larger number of actors and market shaping forces), the more they reduce the freedom of consumers and their agency. Thus, a field which was born to emphasize the shaping role of consumers in market dynamics evolved in such a way that the role of consumers was paradoxically gradually reduced.

We believe that this transition should not be viewed as a shortcoming of MSD studies. Rather, it can be interpreted as a natural evolution of the field toward a more balanced view of market changes, as well as a shift toward meso-level social theories which take the duality of agency and structure (Giddens, 1984; Sewell, 1992) into serious consideration.

Since this transition is now ongoing, we expect the field to become increasingly permeable to theoretical approaches like the institutional work approach (Battilana & D’aunno, 2009; Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006; Lawrence et al., 2009), which relies on a growing awareness of institutions–including markets–by simultaneously taking into account the transformative power of individual and collective action (Kullak et al., 2022). Besides the institutional work approach, we also see great potential in the use of strategic action field (SAF) theory (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012) to explain market dynamics. By borrowing from practice (Bourdieu, 1977; Giddens, 1984), institutional (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, 1977), and social movement theory (Morris & Mueller, 1992; Swaminathan & Wade, 2001), SAF theory makes it possible to focus on how social actors engage in individual and collective practices to change markets, emphasizing their ability to act while mindfully observing and reacting to what others are doing in the market. SAF is suited for use in MSD studies also because it is naturally inclined to historical methods (Pedeliento et al., 2020; Wadhwani, 2018) and is suited to achieving a “more contextual and contested understanding of how institutions interact in particular historical moments, how actors and social movements gain agency to bring about change, how meanings, ideas, and framing matter in this process, and how things change rather than how they stay the same” (Wadhwani, 2018, p. 628). SAF theory can also be very useful for remedying the theoretical imprecision of MSD in its framing of conflicts. Parallel to this, we also believe that further studies should take more serious account of actors’ power endowment and relative influence strategies in order to explain why some dynamics occur. French and Raven’s (1959) classic theory of power can be adapted to explain why some actors succeed in their attempt to change markets while others fail.

Regardless of which theory is used in empirical research, we are convinced that the MSD transition toward a less agentic view of consumers provides this field of study with a valuable opportunity to meet and share the same path as pursued by other research traditions that likewise strive to answer the question of how markets evolve and change. As such, the over-reliance on neo-institutional explanations of market system dynamics should not force the stream into some form of theoretical inertia (Lounsbury et al., 2021). As partly shown by Jafari et al. (2022), we envisage significant opportunities for ‘MSD’ to become an overarching and sufficiently broad label to encompass all scholarly traditions that are similarly coping with market dynamics, regardless of their disciplinary borders, such as, to name only a few, identity-based resource partitioning theory (Carroll & Swaminathan, 2000; McKendrick & Hannan, 2014), status (Bourdieu, 1984; Lamont, 1992; Simmel, 1957; Veblen, 1959) and stigma theory (Goffman, 1963), as well as practice theory (Bourdieu, 1977; Giddens, 1984; Schatzki, 1996) and assemblage theory (Çalışkan & Callon, 2010; DeLanda, 2006; Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). In light of the increasingly predominant role of digital technologies in market assemblages (Schöps et al., 2022), these could also include more recent theoretical tenets that accommodate the affordances of digital environments such as the connective actions logic (Bennett & Segerberg, 2012).

Accordingly, we see great potential in conducting MSD research through the combination of multiple theories, which might not necessarily be grounded in the same ontological or epistemological tradition. As other scholars that have similarly focused on market changes contend (Durand & Thornton, 2018; Negro et al., 2010), markets and their dynamics are a byproduct of complex social negotiations and power relations, and for this reason can hardly be thoroughly understood through a single theoretical device.

Besides the need to enrich the ‘theoretical arsenal’ of MSD, we envisage a trajectory to advance the field which relates to extending the number and type of actors considered in market dynamics. We particularly highlight the need to look more closely at the role played by professional corporations, trade authorities, regulators, policy makers, and other actors that are often responsible for setting the rules regulating the broader social arena in which market dynamics take place and which have been given marginal importance in extant research. To be noted is that these actors are often responsible for a distinctive form of market dynamics hitherto less investigated, which is stability. Trade authorities, policy makers, and professional corporations serve the primary function of maintaining the status quo of some unaltered, to the detriment of the role of others (Thornton & Ocasio, 2008). However, market stability can paradoxically be highly dynamic, because stability itself can be the outcome of the constant work of actors to keep it stable for their benefit.

Partly connected to this, we also envisage promising developments for studies focused on dynamics that have received comparably less attention–with a few exceptions (Baker et al., 2018; Gollnhofer & Kuruoglu, 2018; Parmentier & Fischer, 2015; Valor et al., 2021)–such as market maturity and decline.

Another trajectory for future development of MSD concerns research contexts. The literature analysis that we conducted revealed that MSD research is largely focused on non-mainstream markets, driving the field toward exoticism (Kozinets, 2001, 2002). More research is consequently needed on more traditional markets, such as public utilities, commodities, semiconductors, logistic services, and even B2B equipment. Although these markets are probably less ideologized and less culturalized than others, they are equally highly dynamic. For example, the current market for gas and electric power can be fruitfully investigated through the lens of MSD, because current price pressures result from the complex interplay of social, political, military, supra-national, and environmental forces. Similarly, because at present investigations on low-tech markets outnumber those on high-tech markets, more studies are needed on tech-driven markets and on the generative power of technologies in shaping market dynamics.

Again in regard to contexts, the reconstruction of MSD studies shows a net prevalence of research in the Western world. Now more than ever, in a world in which East-West cultural tensions are rising again from the ashes of the Cold War, fueled by the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, more research is needed not only to understand how market dynamics occur and assume different forms in non-Western contexts, but also–and primarily–how markets amplify a Western/Eastern antagonistic ethos.

Finally, research methodologies and methods are a further (and very promising) avenue for MSD development. First, we advocate truly historical market inquiries, spanning longer timeframes such as decades or even centuries. As put forth by ‘history in theory’ approaches (Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Maclean et al., 2016), only such long spans can yield a comprehensive conceptualization of market dynamics. Moreover, if one accepts the idea that theoretical pluralism is needed to explain complex market phenomena, such theoretical pluralism requires methodological pluralism and must be open to quantitative measurements (Huff et al., 2021) or quali-quantitative analyses (Aranda et al., 2021). Quantitative approaches can greatly help and complement interpretivist market inquiries on MSD. For example, the computation of firm-concentration ratios has proven helpful for illustrating resource partitioning dynamics (Carroll & Swaminathan, 2000). In this vein, Watts (2018) suggests that synthetic language-based models of market dynamics could aid qualitative market inquiries because they would make it possible to collect large amounts of market-related textual data, and to identify ‘entry points’ for more in-depth analysis of discrepancies in observed behaviors (Arnould & Wallendorf, 1994). Moreover, we contend that research designs that lie at the intersection of quali-quantitative epistemologies can provide multiple opportunities to advance MSD research (DiMaggio et al., 2013; Hannigan et al., 2019). In fact, there is a fertile tradition in disciplines such as sociology, management and organization studies, which successfully employ quali-quantitative methodologies to unpack the multifaceted dynamics of culture, meanings, and materiality (DiMaggio et al., 2013; Höllerer et al., 2019; Kozlowski et al., 2019; Mohr et al., 2020). Since markets are increasingly embedded in texts (Humphreys, 2021) and images (Belk, 2011), we contend that methodologies such as topic modeling and the broader field of text and image mining could be adopted for the cultural analysis of market system dynamics, because these methodologies are able to accommodate heteroglossia and relationality of meaning, and to navigate through volumes of data that would be unmanageable with manual approaches (DiMaggio et al., 2013). Similarly, acknowledging the platformization and digitalization pressures that fragment markets through novel affordances (Van Dijck, 2021), we invite future scholars to expand their analysis of markets to include methods that exploit the online grounding of web-mediated market transactions and that allow the navigation of networked digital market assemblages (Rogers, 2019; Schöps et al., 2022).

Limitations and implications

The literature review reported by this paper was intended to establish clear intellectual boundaries for the research field known as MSD, and to determine how it has evolved since its inception. The historical reconstruction of studies published from 2003 to 2022 made it possible to fulfil both these aims. However, the results, the theoretical contributions, and the developmental trajectories that we advance in this research must be viewed in the light of its limitations. The first limitation concerns the data collection strategy and the criteria we used to include/exclude research contributions in our dataset and which led to the exclusion of book chapters and conference papers. Although book chapters and conference proceedings are often the main outlets in which new and unorthodox research ideas are proposed and advanced before they gain traction and become mainstream, we decided to limit our analysis to published papers alone for the sake of robustness, reliability, and replicability of the methodology. In fact, while we can reasonably assert that all of the relevant research on MSD has been published by indexed journals, we cannot do the same about book chapters and conference proceedings. Thus, including these research outputs would have increased arbitrariness in the search strategy and would have added subjectivity to the research results and to the interpretations of them that we provide.

A second limitation relates to overreliance on Giesler and Fischer’s (2017) tenets. Although this contribution provides a valuable and easily actionable intelligible lens through which to make sense of the historical evolution of the MSD field since its inception, we are aware that other lenses could have been used and would have led to different interpretations of the field’s evolution. For example, acknowledging MSD’s coupling with CCT, a critical analysis of the literature could have been conducted using the four ‘tenets’ of CCT, i.e., (1) consumer identity projects, (2) marketplace cultures, (3) the sociohistoric patterning of consumption, and (4) mass-mediated marketplace ideologies and consumers’ interpretive strategies (Arnould & Thompson, 2005), leading to different conclusions and perhaps to the plotting of different developmental paths.

The last limitation, partly connected with the previous one, relates to our use of Giesler and Thompson’s (2016) tutorial for theorizing change. Because this tutorial was issued to assess the relative level of consumers’ enrollment in market dynamics, it implicitly left aside the degree of enrollment of other (market and non-market related) actors which may be responsible for bringing about transformative, topological or disruptive forms of market change. For example, the adoption of a different approach whereby attention was paid to firms or to policy makers as actors of change, would have led to a different picture of market dynamics.

Notwithstanding its theoretical nature, this study has some implications for marketing practice. First, the three biases that MSD tries to resolve are not limited to the academic domain but have equal impact on marketing practice. In the current markets (including both consumer and business markets), marketers should be ever more sensitive to macro-cultural, historical and market-level structures and forces that shape consumption practices and culture (micro level bias). They should downplay the tendency to focus almost exclusively on consumers and competitors. They should be more open to a view of markets that acknowledges the presence of a wider array of actors (economic actor bias). Finally, they should seek more complex explanations as to why some dynamics are happening by adopting a longitudinal, developmental approach rather than limiting the scope of their focus to discrete variables. Consequently, it is not surprising that the number of practitioners interested in gaining a deeper understanding of the overly complex dynamics of markets is constantly on the rise (Wieland et al., 2021).

A second practical implication, partly connected with the previous one, relates to the pertinence of MSD and, more in general, of the systemic thinking of markets to achieve a finer-grained understanding as to why some market phenomena are happening and how markets are transforming and, possibly, to foresee market dynamics before they materially take place. Marketers equipped with a systemic thinking to markets and to market dynamics can more promptly identify trends and change dynamics taking place in fields that have very weak connections with their market arenas but that, nevertheless, can trigger significant changes in their status quo. Macro issues like global warming, climate change, or gender equality, which exist regardless of markets, have been successfully commodified by marketers to give their products and brands a different positioning and to modify the rules of the game in their favor. A brand like Patagonia for example, that has long been active in raising awareness about global warming and climate change (Holt & Cameron, 2010), has not only surfed this broad social discourse to obtain a unique positioning for its brand and products, but has also intentionally or unintentionally radically shifted the fashion industry toward a new sustainable logic (Ertekin et al., 2020).

References

Appadurai, A. (Ed.). (1988). The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Aranda, A. M., Sele, K., Etchanchu, H., Guyt, J. Y., & Vaara, E. (2021). From big data to rich theory: Integrating critical discourse analysis with structural topic modeling. European Management Review, 18(3), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12452.

Araujo, L. (2007). Markets, market-making and marketing. Marketing Theory, 7(3), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593107080342.

Araujo, L., Finch, J., & Kjellberg, H. (2010). Reconnecting marketing to markets. Oxford University Press.

Arnould, E. J., & Thompson, C. J. (2005). Consumer culture theory (CCT): Twenty years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 868–882. https://doi.org/10.1086/426626.

Arnould, E. J., & Wallendorf, M. (1994). Market-oriented ethnography: Interpretation building and marketing strategy formulation. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(4), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379403100404.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

Askegaard, S., & Linnet, J. T. (2011). Towards an epistemology of Consumer Culture Theory. Marketing Theory, 11(4), 381–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593111418796.

Augier, M., March, J. G., & Sullivan, B. N. (2005). Notes on the evolution of a research community: Organization studies in Anglophone North America, 1945–2000. Organization Science, 16(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0108.

Bajde, D., Chelekis, J., & van Dalen, A. (2022). The megamarketing of microfinance: Developing and maintaining an industry aura of virtue. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 39(1), 134–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.05.004.

Bajde, D., & Rojas-Gaviria, P. (2021). Creating responsible subjects: The role of mediated affective encounters. Journal of Consumer Research, 48(3), 492–512. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucab019.

Baker, J. J., & Nenonen, S. (2020). Collaborating to shape markets: Emergent collective market work. Industrial Marketing Management, 85, 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.11.011.

Baker, J. J., Storbacka, K., & Brodie, R. J. (2018). Markets changing, changing markets: Institutional work as market shaping. Marketing Theory, 19(1), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593118809799.

Battilana, J., & D’aunno, T. (2009). Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency. In T. B. Lawrence, L. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organizations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511596605.002.

Bauman, Z. (2013). Liquid modernity. John Wiley & Sons.

Belk, R. (2011). Examining markets, marketing, consumers, and society through documentary films. Journal of Macromarketing, 31(4), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146711414427.

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139198752.

Biraghi, S., Gambetti, R., & Pace, S. (2018). Between tribes and markets: The emergence of a liquid consumer-entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 92, 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.018.

Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth (Vol. 27). Princeton University Press.

Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. Sage Publishing.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinctions: A Social Critique of the Judgment of taste. Harvard University Press.

Branstad, A., & Solem, B. A. (2020). Emerging theories of consumer-driven market innovation, adoption, and diffusion: A selective review of consumer-oriented studies. Journal of Business Research, 116, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.028.

Brei, V., & Tadajewski, M. (2015). Crafting the market for bottled water: A social praxeology approach. European Journal of Marketing, 49(3–4), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2013-0172.

Callon, M. (1998). The laws of the Markets. Blackwell.

Çalışkan, K., & Callon, M. (2010). Economization, part 2: A Research Programme for the study of markets. Economy and Society, 39(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903424519.

Carroll, G. R. (1985). Concentration and specialization: Dynamics of niche width in populations of organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 90(6), 1262–1283. https://doi.org/10.1086/228210.

Carroll, G. R., & Swaminathan, A. (2000). Why the microbrewery movement? Organizational dynamics of resource partitioning in the US brewing industry. American Journal of Sociology, 106(3), 715–762. https://doi.org/10.1086/318962.

Collet, B., & Rémy, E. (2022). Exploring the (un)changing nature of cultural intermediaries in digitalised markets: Insights from independent music. Journal of Marketing Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2022.2118814. (forthcoming).

Commons, J. R. (1950). The economics of collective action. University of Wisconsin

Coskuner-Balli, G. (2013). Market practices of legitimization: Insights from consumer culture theory. Marketing Theory, 13(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593113477888.

Coskuner-Balli, G., & Ertimur, B. (2016). Legitimation of hybrid cultural products. Marketing Theory, 17(2), 127–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593116659786.

Coskuner-Balli, G., Pehlivan, E., & Üçok Hughes, M. (2021). Institutional work and brand strategy in the contested Cannabis Market. Journal of Macromarketing, 41(4), 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/02761467211029243.

Coskuner-Balli, G., & Tumbat, G. (2017). Performative structures, american exceptionalism, and the legitimation of free trade. Marketing Theory, 17(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593116657919.

Debenedetti, A., Philippe, D., Chaney, D., & Humphreys, A. (2020). Maintaining legitimacy in contested mature markets through discursive strategies: The case of corporate environmentalism in the french automotive industry. Industrial Marketing Management, 92, 332–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.009.

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. University of California Press.

DeLanda, M. (2006). Deleuzian social ontology and assemblage theory. In. In M. Fuglsang, & B. M. Sorensen (Eds.), Deleuze and the Social. Edinburgh University Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A Thousand Plateaus. University of Minnesota Press.

Delmestri, G., Wezel, F. C., Goodrick, E., & Washington, M. (2020). The Hidden Paths of Category Research: Climbing new heights and slippery slopes. Organization Studies, 41(7), 909–920. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620932591.

DeQuero-Navarro, B., Stanton, J., & Klein, T. A. (2020). A panoramic review of the Macromarketing Literature. Journal of Macromarketing, 41(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146720949636.

Diaz Ruiz, C., & Makkar, M. (2021). Market bifurcations in board sports: How consumers shape markets through boundary work. Journal of Business Research, 122, 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.039.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101.

DiMaggio, P., Nag, M., & Blei, D. (2013). Exploiting affinities between topic modeling and the sociological perspective on culture: Application to newspaper coverage of US government arts funding. Poetics, 41(6), 570–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.004.

Dolbec, P. Y., & Fischer, E. (2015). Refashioning a field? Connected consumers and institutional dynamics in markets. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1447–1468. https://doi.org/10.1086/680671.

Douglas, M. (2002). Purity and danger. Routledge Classics.

Durand, R., & Thornton, P. H. (2018). Categorizing institutional logics, institutionalizing categories: A review of two literatures. Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 631–658. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0089.

Edwards, D. (1999). Emotion discourse. Culture & Psychology, 5(3), 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X9953001

Elder, G. H. Jr., & Shanahan, M. J. (2006). The Life Course and Human Development. In R. M. Lerner, & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (pp. 665–715). John Wiley & Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0112.

Ertekin, Z. O., & Atik, D. (2020). Institutional constituents of change for a sustainable fashion system. Journal of Macromarketing, 40(3), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146720932274.

Ertekin, Z. O., Atik, D., & Murray, J. B. (2020). The logic of sustainability: Institutional transformation towards a new culture of fashion. Journal of Marketing Management, 36(15), 1447–1480. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1795429.

Ertimur, B., & Chen, S. (2020). Adaptation and diffusion of renovations: The case of the paleo diet. Journal of Business Research, 116, 572–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.015.

Ertimur, B., & Coskuner-Balli, G. (2015). Navigating the Institutional Logics of Markets: Implications for Strategic Brand Management. Journal of Marketing, 79(2), 40–61. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.13.0218.

Evans, P. (1995). Embedded autonomy: States and industrial transformation. Princeton University Press.

Ewen, S. (1988). All consuming images: The politics of style in contemporary culture. Basic.