Nearly two years after the Granston Memo, DOJ attorneys are taking a closer look at whistleblower cases and have dismissed more cases than before the guidance. DLA Piper attorneys say this increased gatekeeper function has caused a sharp judicial split, and a stop at the U.S. Supreme Court may be next.

When the Justice Department issued the so-called “Granston Memo” in January 2018 instructing government attorneys to seriously consider dismissing more non-intervened qui tam lawsuits under the False Claims Act , many questioned what real-world effects it would have.

Nearly two years later, the consequences have proved significant. First, the DOJ has moved to dismiss many more cases than it had ever done previously. Second, this flurry of DOJ gatekeeping activity has amplified an existing circuit split concerning the level of deference the DOJ is owed when it seeks dismissal.

Increased DOJ Gatekeeping Activity

Section 3730(c)(2)(A) of the FCA, enacted in 1986, empowers the DOJ to dismiss qui tam lawsuits over a relator’s objection, provided the relator receives “an opportunity for a hearing on the motion.”

Prior to the Granston Memo, the DOJ exercised this statutory authority sparingly, moving to dismiss only one to two qui tam cases per year (for reference, 600-700 new FCA complaints are filed annually). In the last two years, however, DOJ has moved to dismiss at least 24 qui tam cases—a significant spike.

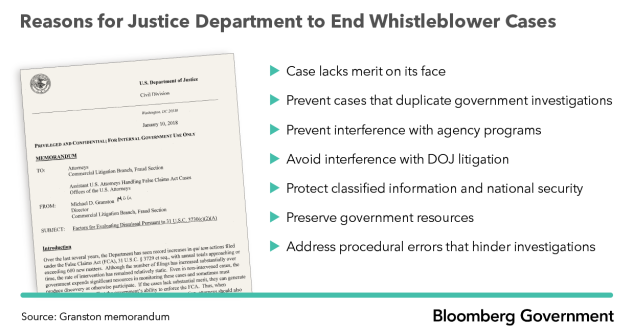

The Granston Memo asks DOJ attorneys to dismiss non-intervened cases when doing so would “advance the government’s interests, preserve limited resources, and avoid adverse precedent,” and the memo identifies a non-exhaustive list of seven factors government lawyers should consider.

We have analyzed the (c)(2)(A) motions filed since the Granston Memo and found the government has cited three of the Granston factors most often:

- preservation of government resources (cited 100% of the time);

- curbing meritless qui tams (cited about 80% of the time); and

- preventing interference with agency policies and programs (cited about 50% of the time).

And in about half of the government’s post-Granston Memo motions, the DOJ also criticized the relators’ conduct.

For example, in 10 cases, the DOJ derided a “shell company relator” that “utilized the same model or template [complaints]” gleaned from “information obtained under false pretenses” under the “guise of conducting a ‘qualitative research study.’”

Although the DOJ did not explicitly state that thwarting dubious relators is a “valid government purpose” justifying dismissal, the department clearly does not want to support opportunistic relators it views as wrongfully pursuing a windfall.

Notwithstanding this significant increase in dismissal motions, Michael Granston, director of the DOJ’s Civil Fraud Section, has noted that “dismissal [under § 3730(c)(2)(A)] will remain the exception, not the new rule,” putting defendants “on notice that pursuing undue or excessive discovery will not constitute a successful strategy for getting DOJ to exercise its dismissal authority.”

The DOJ may want to convey a business-as-usual message—likely to stem a wave of litigant requests—but the fact remains that the department has been unusually busy moving to end FCA lawsuits across the country.

The Deepening Circuit Split

Even before the Granston Memo, courts wrestled with the appropriate standard to apply when assessing government dismissal motions.

The Ninth Circuit adopted a two-step standard in Sequoia Orange v. Sunland Packing House Co. (1998), holding that dismissals are warranted only if the DOJ has demonstrated:

- a valid government purpose and

- a rational relationship between dismissal and that purpose.

If the government makes the required showing, the burden shifts to the relator to demonstrate that the government’s action was “fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal.”

The Tenth Circuit has essentially endorsed the Sequoia Orange standard, ruling that dismissal is warranted if there are any “plausible, or arguable, reasons” supporting a government motion to dismiss.

The D.C. Circuit, on the other hand, rejected Sequoia Orange on a separation-of-powers basis in Swift v. United States (2003), reasoning that “decisions not to prosecute, which [are] what the government’s judgment [] amounts to, are unreviewable” and, thus, the DOJ has an “unfettered right to dismiss” a qui tam action.

Although the deference owed under either standard is high, the Granston Memo urges federal prosecutors to advocate adoption of the Swift standard in all cases.

Unsurprisingly, the recent surge of (c)(2)(A) motions has led lower courts to revisit the competing standards, and the resulting decisions reflect the ongoing split. Since 2018, district courts have granted 10 dismissal motions using the Swift standard, including nine outside the D.C. Circuit, where Swift is binding.

Some courts, however, have adopted the less-deferential Sequoia Orange standard. Indeed, two courts have denied government motions for failure to satisfy Sequoia Orange, with one noting that Swift “renders the hearing specifically provided for in the statute superfluous and belies the role of the judiciary in ensuring constitutional checks and balances.”

In denying the government’s motion, the court said it would not “blindly accept the Government’s stated reasons for dismissal.”

In the wake of these district court decisions, the Second, Fifth, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits have been asked to weigh in. Given the increasing volume of cases and sharp judicial split, the Supreme Court may well be next.

Takeaways

The DOJ is increasingly willing to exercise its statutory authority to dismiss qui tam actions. This development carries both opportunities and risks that must be weighed carefully by litigants considering advocating for DOJ action in any particular case.

Litigants should take care to evaluate the extent to which the circumstances and key factors present in their own cases mirror those present in cases in which the DOJ has elected to bring a (c)(2)(A) motion.

While the uptick in these dismissals may be a positive development for litigants, both the government and the courts will clearly remain cautious when blocking relators from proceeding with an FCA lawsuit.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. or its owners.

Author Information

Eric Christofferson is a former federal prosecutor and an experienced litigation and compliance lawyer in DLA Piper’s Boston office. His practice focuses on the life-sciences and financial-services sectors, representing clients in government and internal investigations, criminal and regulatory proceedings, and civil litigation..

Andrew Hoffman II, a partner in DLA Piper’s Los Angeles office, focuses his practice on representing pharmaceutical manufacturers and other life sciences companies in government investigations and related litigation.

Colleen M. McElroy, an associate in DLA Piper’s Los Angeles office, represents life sciences companies in litigation and regulatory enforcement matters.

The authors would also like to acknowledge Anthony Portelli, formerly of DLA Piper, for his contribution to this article.

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

Learn About Bloomberg Law

AI-powered legal analytics, workflow tools and premium legal & business news.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools.