Key points

Far-reaching changes in the global balance of power and Europe’s security environment call for a new U.S. strategy toward Europe—for the benefit of Americans and Europeans alike.

European states should take deliberate steps toward autonomy in defense, which the U.S. should foster by reducing its military presence in, and security commitments to, Europe, gradually and in coordination with its NATO allies. The eventual goal should be to eliminate permanent U.S. military deployments in Europe.

Europe, particularly France and Germany, possesses the material wherewithal to balance Russia’s military power. What Europe lacks is the motivation, something it will not acquire so long as it can count on a blanket, open-ended American commitment.

Europe’s stability and security demand a regional order into which Russia—the continent’s strongest single military power—is eventually integrated, rather than one from which it has become progressively alienated.

The post-Cold War crises over Ukraine arose from complex circumstances; but one of them has been the absence of a pan-European security order that extends from the Atlantic to the Urals and contains provisions for engagement with Russia, including arms control and crisis management, as well as confidence-building measures designed to reduce the risk of war.

Restructuring Europe’s security order to promote European strategic autonomy will improve, not harm, trans-Atlantic relations and cooperation. The U.S. and Canada are bound to Europe by centuries-old ties—historical, cultural, and economic. While the extent and nature of these ties will necessarily change over time, their existence does not depend on an American willingness to serve indefinitely as Europe’s prime defender.

EUROPE’S SECURITY ORDER IS ARCHAIC

NATO expansion and perpetual crises if Europe’s security order excludes Russia

Not every dispute between Russia and Ukraine or Russia and Georgia can be chalked up to NATO expansion.1 Yet the denial of any connection flies in the face of the evidence. Every post-Cold War Soviet and Russian leader (Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, and Vladimir Putin) has condemned NATO expansion. Moreover, Russia’s preoccupation with, and antipathy toward, that project reflects a historical pattern: great powers seek spheres of influence and resist adversaries’ attempts to establish a military presence within them.2 That may not be commendable or desirable, but it does mean Russia’s behavior cannot reasonably be viewed as aberrant or indeed wholly different from that of other great powers, including the United States.

Seen thus, the 2014–2015 and 2021–2022 crises centering on Ukraine were not purely bilateral ones between Ukraine and Russia. They resulted, in part, from Washington’s failure to seize the opportunity afforded by the end of the Cold War—the “unipolar moment,” when the United States wielded unprecedented, peerless power—to forge a pan-European security order that extended from the Atlantic to the Urals (as the USSR’s last leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, put it) and included Russia. The decision to expand NATO excluded Russia from the new European order, whereas a Europe-wide system would have laid the foundation for far-reaching arms control and confidence-building measures, strengthening the security of a Europe, newly conceived.3 Such measures as were taken to include Russia were never so far reaching.4 Instead, the thinking about the continent’s future was timid and, worse, stuck in the past.

American leaders may speak in general terms about the desirability of a European order that integrates Russia, but such an arrangement would diminish, and over time perhaps even destroy, U.S. primacy in Europe. Russia is too large, powerful, and independent to accept a European order in which the United States’ preferences on critical matters tend to prevail. The desire to preserve the United States’ preeminent position within NATO may explain Washington’s choice not to include Russia in the alliance once it began to expand after the Cold War.

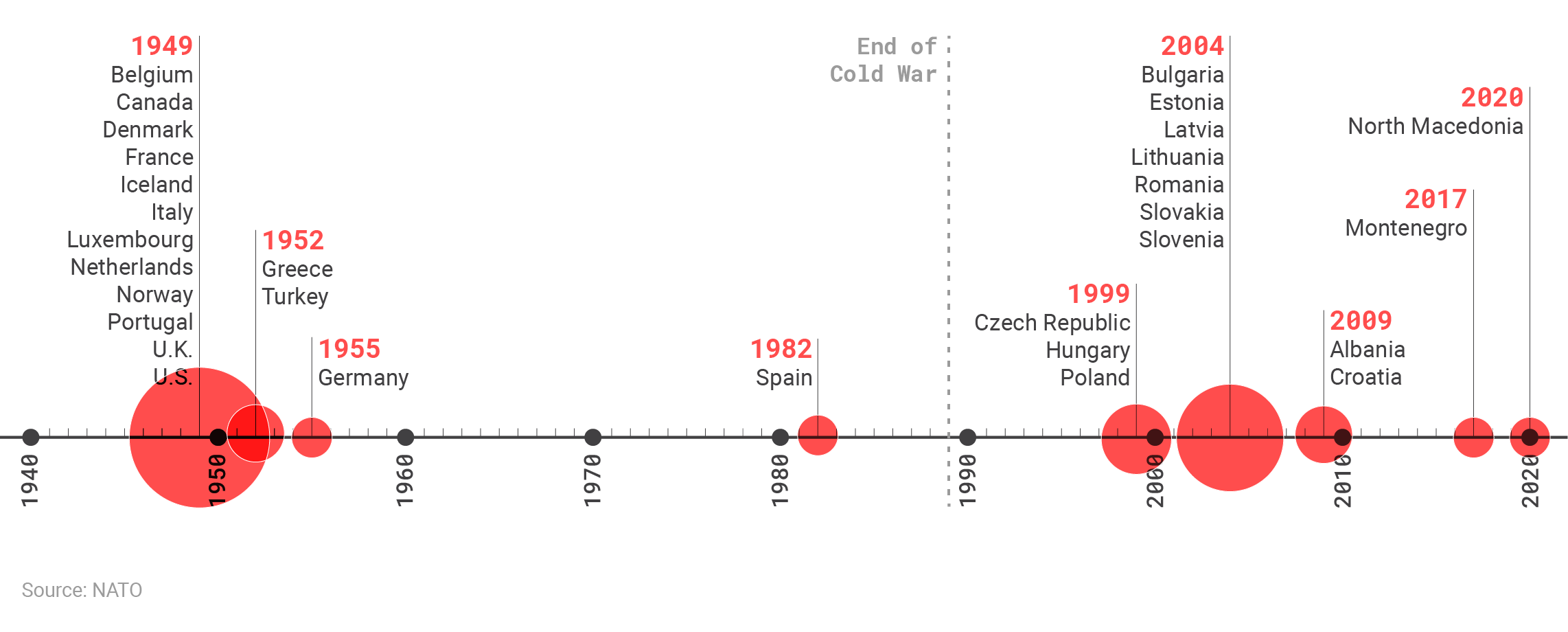

NATO expansion timeline

Post-Cold War NATO expansion not only obligated the United States to defend countries marginal to U.S. national security, but also contributed to crises with Russia involving Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014–2015, 2021–2022).

Russia’s alienation from a European order marked by U.S. primacy and NATO enlargement also contributed to the demise of arguably the most significant arms control agreement in modern European history: the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. The INF Treaty eliminated all U.S. and Soviet ballistic and cruise missiles with a range between 550 and 5,000 kilometers from Europe (and, in Russia’s case, Asia as well).5 Opportunities to build upon previous conventional (non-nuclear) arms control treaties, such as the 1990 Conventional Arms Forces in Europe Treaty, were also lost. Russia and the United States charged one another with violating these agreements, but their differences should have been resolved through negotiations, so that those accords could continue to contribute to European security.

A new European security order should include regular diplomatic and military-to-military exchanges with Russia. Discussions within these forums could help prepare the groundwork for confidence-building measures that reduce the risk of the frequent, close, and dangerous encounters between the two countries’ warships and military aircraft in and around the Baltic Sea and Black Sea—something that has occurred on several occasions—creating accidents that could spiral into a conflict between the world’s two nuclear superpowers.6

NATO continually underscores the magnitude of Russian power and the threat it poses to Europe, but maintaining forces required to deter Russia should not preclude steps toward a new European security system in which it acquires a stake. Yet NATO remains divided on whether to engage Russia. Even those members of the alliance who favor engagement are not of one mind on what the agenda for engagement should be, the extent to which engagement should be pursued, and the ends it should seek.

Within NATO, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland are the least enthusiastic about formulating a new approach toward Russia that would have a distinctive European stamp.7 They are also the most fervent opponents of strategic autonomy aimed at military self-sufficiency on the continent, or even a reduced U.S. military presence.

Global nuclear warhead totals by country

The United States and Russia control approximately 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons, which makes avoiding direct conflict between them paramount.

The United States nevertheless has good reasons to change course in Europe, among them China’s rise, the relative decline in American economic power, and festering social and economic problems at home.8 And as the 2021–2022 crisis with Russia demonstrated, the American security guarantee to an enlarged NATO has created more demanding defense commitments to its eastern flank now that a stronger Russia has emerged. The consensus in Washington is that China presents the principal challenge to American primacy, and Americans are increasingly concerned about problems on the home front.9 Under these circumstances, better to formulate a new approach to Europe with care and deliberation than to change course abruptly because of events in the Asia-Pacific.

Update our Cold War strategy for today’s geostrategic realities

The premises and practices that underpin current U.S. strategy toward Europe amount to a tweaking of those that prevailed during the Cold War, never mind that the conditions in Europe are now wholly different. Europe has long since become an economic and technological powerhouse, even a rival of the United States in global markets. No country with military power comparable to the Soviet Union now threatens the European balance of power (Ukraine is not critical to that balance). The European Union, most of whose members also belong to NATO, has a GDP that is more than nine times larger than Russia’s: €13 trillion versus €1.4 trillion. Europe is also technologically far superior to Russia.10 Clearly, then, Europeans have the material wherewithal to develop the capacity to deter Russia.

Perils of primacy: wealthy allies can outsource national defense

Now is the time for the United States to champion Europe’s strategic autonomy. Not only has it failed to do so, but it has also steadfastly opposed the idea. Instead, it complains intermittently about the inequitable defense burden within NATO while allowing it to persist.11 Rather than harping on burden sharing, the United States should move toward “burden shifting” that begins with reductions in American forces and eventually leads to European self-sufficiency in defense and the elimination of a permanent U.S. military presence. That change need not involve the jettisoning of NATO.

Because the United States has not demanded more of its European NATO allies, their progress toward meeting the benchmarks adopted at the 2014 Wales Summit for national defense spending (2 percent of GDP) and military procurement (20 percent of the military budget) has, unsurprisingly, been spotty at best, something NATO’s most recent figures make clear.12 Moreover, Germany, Europe’s wealthiest state, is among the biggest laggards. Not only has Germany still not met the Wales targets, but the Bundeswehr is also inadequately funded, understaffed, and lacks all manner of equipment and spare parts.13 Had the Wales benchmarks been met, European defense spending would have increased by billions of dollars.

The curious upshot has been that an increasing preoccupation with the Russian threat coexists with Europeans’ failure to take the steps needed to address it.

Codependency and thwarting “Strategic Autonomy”

Europeans have become accustomed to a regional security order that has persisted for over seven decades and features a permanent U.S. military presence and security guarantee.14 If one is a European, what’s not to like?

This arrangement goes beyond European dependency on the United States. It resembles what psychologists call codependency, with a provider and a recipient, each locked into their roles and unable to construct an alternative. The dynamic persists because American leaders do not want a change in the status quo. One of the enduring legacies of post-World War II American primacy is the U.S. foreign and national security community—the executive and legislative branches of government, the media, academic specialists, and think tanks—remains convinced a stable world order cannot exist unless the United States maintains, and regularly displays, its preponderance, lest adversaries become challengers and dominoes start to fall. The habitual invocation of “credibility” owes to this mindset.15

NATO presence in Eastern Europe

NATO’s presence in eastern Europe, marked by U.S. missile shields and battlegroups, antagonizes Russia with no real strategic payoff.

A NEW, STRONGER SECURITY ORDER FOR EUROPE

Burden shifting: Europeans are wealthy and can field modern military power

Europe can defend itself and should do far more for its own defense than it does now.16 In addition to spending more on their own defense, European countries should develop an independent conception of security that progressively moves their continent toward autonomy. First, they should eradicate the problems that impair military effectiveness. A case in point: the shortage of the most basic equipment and essential parts for warships, warplanes, and submarines that plague the Bundeswehr, the army of Europe’s richest nation.17 Next, Europe should develop plans to harmonize defense production, especially by coordinating defense spending and replacing duplicative weapons production with a European-wide division of labor based on comparative advantage. This will not be easy because of the pressure leaders will inevitably face to keep production and jobs within their countries and to support national defense industries. Still, there is a difference between defense production based on national autarchy and a collective approach. The latter would exploit opportunities for various forms of collaboration, including coproducing armaments, divvying up different parts of the production process, and exploiting comparative advantages.

Whether and to what degree greater European strategic self-sufficiency is worked out in cooperation with the United Kingdom should be a matter for Europeans to decide. The same goes for whether strategic autonomy coexists with a reformed NATO or eventually replaces the alliance. The change should be implemented through close consultation between the United States and its allies and at a pace that does not create needless disruptions.

A new regional order

Because of the economic and military distribution of power in Europe, Germany, the continent’s wealthiest country, and France, its sole full-service military power (the pair have a GDP 87 percent greater than Russia’s but combined spend more than $60 billion less on military expenditures based on Purchasing Power Parity, or PPP), will have to take responsibility for ushering Europe toward strategic autonomy.18 It is desirable for them to work in tandem because of the residual suspicions that linger about a Europe dominated by Germany. Under French President Emmanuel Macron at least, the French government has forcefully advocated for European strategic autonomy (most recently during the 2021–2022 Ukraine-Russia crisis), arguing Europe should have an independent voice and collective vision on continental security.19

French and German vs. Russian military expenditures (PPP)

France and Germany, two populous, technologically advanced, and wealthy nations, have the capacity to anchor a new strategic order in Europe.

As part of a new strategy toward Europe, the United States should help create a new regional order—one that integrates, rather than estranges, Russia. Alienating Russia, as it has been for most of the post-Cold War decades, has resulted in steadily increasing crises in eastern Europe.

The expansion of NATO—which has grown from 16 members at its Cold War highpoint to 30 in 2022—is but one part of the problem between Russia and the West, but it is a big one. Influential Americans nevertheless insist Russia’s concerns about the advance of a Cold War alliance toward its borders are contrived and unrelated to security. They regard the Russian president’s objections as a ruse to mask his (“real”) fear, namely that democracy could spread to adjacent countries and eventually threaten Russia’s authoritarian political order.20 While this may be true in part, a sound grand strategy must include an awareness that other countries may not share American perceptions and indeed may reject them wholesale.21

What the United States sees as benign (NATO expansion or European missile defense) Russia regards as threatening. A sound strategy also requires the willingness and capacity to understand how other countries perceive one’s actions and the humility to resist the urge to believe that you know what other countries’ actual interests and fears are. None of this means conceding what rivals want, let alone appeasement; it does mean a willingness to understand the world as they see it so that pathways can be found to advance U.S. interests and avoid crises and war through reasonable compromise.22 As former Secretary of State James A. Baker put it, “I would have to say that if there was one key to whatever success I’ve enjoyed in negotiating…it has been an ability to crawl into the other guy’s shoes. If you understand your opponent, you have a better chance of reaching a successful conclusion. That means paying attention to how they view issues and appreciating the political constraints they face.”23

Benefits of a new order for the U.S. and Europe

European strategic autonomy will benefit the United States and Europe given changes occurring in the global distribution of power. American attention and resources will swing increasingly toward the Indo-Pacific. For all the talk about the Russian threat, it is China that American leaders regard as the true “peer competitor.”

Calculated in PPP, the United States has a GDP of $20.9 trillion compared to Russia’s $4.1 trillion24 and a defense budget of $731 billion versus Russia’s $166 billion.25 The United States also remains far superior to Russia on the technological front, including in the military sphere.26 By contrast, China has overtaken the United States to become world’s largest economy, when GDP is measured based on PPP, and has pulled even when the comparison is made using exchange rates.27 According to managers of leading global hi-tech companies, China has also narrowed the technological gap.28 For example, its massive investments in robotics and artificial intelligence have begun to pay off.29

The belief that European strategic autonomy and a reduced U.S. military burden will cause trans-Atlantic bonds to fray and eventually break is wrong. It amounts to an impoverished, indeed militarized, understanding of what creates common ground between people in the United States and Canada and those in Europe. They are connected by history, culture, language (consider how many Europeans are fluent in English), trade, an array of financial transactions, tourism, and partnerships among universities and myriad civil society groups. NATO has certainly been an important bridge—but it is not the irreplaceable foundation: shared interests and values are.

A new European security order—stronger United States, stronger allies, and a more stable Europe

It is the responsibility of Europeans to develop a new order for their continent.30 They will gain greater agency and control over their future. They will, in particular, be better prepared to defend themselves once the focus and military resources of the United States move to East Asia. For now, the status quo suits the Europeans and seems unlikely to change because the consensus in the United States remains that it must be maintained. Europeans may even believe the combination of the United States’ commitment to primacy and its preoccupation with credibility will ensure the continuation of the American defense commitment. That may, however, prove to be a risky bet for the long term. The question for Europeans is whether they can count indefinitely on their preferred arrangement given that American priorities may change in response to the changes underway in the global balance power.

For the United States, reducing, if not eliminating, the costs of defending Europe will free up funds—as much as $80 billion a year—that could be used to meet defense-related needs elsewhere and to address problems festering on the home front.31 If a Europe capable of defending itself emerges, the United States will gain more leeway to reorder its strategic priorities. The claim that the costs to the United States are minimal not only makes light of an expenditure that is scarcely trivial; more important, it sidesteps the key point: Europe does not lack the resources needed for self-defense.

There are two commonplace objections to the idea of European strategic autonomy. The first is that without the American defense guarantee Europe will revert to disunity, even conflict. The other is that the large number of European states will bedevil regional cooperation on security. But instability in Europe, while a possibility, is but one conceivable outcome. The extensive interdependence within Europe (intra-E.U. exports approached $300 billion in 2020, and for most members, exports within the European Union accounted for between 50 and 75 percent of their total exports), the continent’s embrace of democracy, and the European Union and its supranational organizations will, together, help prevent conflict and ease cooperation.32 The European Union has central institutions and a common currency (within the eurozone) and bank; and the European states party to the Schengen Agreement have eliminated border controls—all while increasing the number of member states. This achievement demonstrates a multiplicity of sovereign states can in fact cooperate extensively, indeed to a point verging on integration. Besides, the claim that Europeans cannot manage their own affairs without an American military presence amounts to saying that current American strategy toward the continent must continue indefinitely, regardless of changing conditions on the home front and the redistribution of power in the world.

The 2021–2022 crisis pitting Russia against Ukraine and NATO might suggest that even gradual moves to end the U.S. military deployment in Europe would be dangerous. In fact, the lesson to be drawn is that the confrontation mattered far more to Europe’s security than to that of the United States. President Biden’s scramble to reassure the alliance’s eastern flank by deploying some 5,000 American troops to Germany, Poland, and Romania underscores Europe’s lack of preparedness to defend itself—a situation it finds itself in by choice and because of its attachment to a long-established status quo, not for want of resources that can be marshaled for self-defense.33

Endnotes

1 Rajan Menon and William Ruger, “NATO Enlargement and U.S. Grand Strategy: A Net Assessment,” International Politics, vol. 57, no. 3 (2020): 371–400; Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion,” International Security, vol. 40, no. 4. (Spring 2016): 7–44; M.E. Sarotte, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022).

2 Jonathan Masters, “Why NATO Has Become a Flash Point with Russia in Ukraine,” Council Foreign on Relations, January 20, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/why-nato-has-become-flash-point-russia-ukraine.

3 Masters, “Why NATO Has Become a Flash Point.”

4 Sarotte, Not One Inch: 301–335.

5 Shannon Bugos, “U.S. Completes INF Treaty Withdrawal,” Arms Control Association, September 2019, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2019-09/news/us-completes-inf-treaty-withdrawal.

6 Ralph Clem, “Risky Encounters with Russia: Time to Talk About Real Deconfliction,” War on the Rocks, February 18, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/02/risky-encounters-with-russia-time-to-talk-about-real-deconfliction/; Ralph Clem and Ray Finch, “Crowded Skies and Turbulent Seas: Assessing the Full Scope of NATO-Russian Military Incidents,” War on the Rocks, August 19, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/crowded-skies-and-turbulent-seas-assessing-the-full-scope-of-nato-russian-military-incidents/.

7 Liz Sly, “Europe Divided in Confronting Russia over Ukraine,” Washington Post, January 23, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/01/23/europe-divided-ukraine/.

8 Yen Nee Lee, “Here Are 4 Charts that Show China’s Rise as a Global Economic Superpower,” CNBC, September 23, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/24/how-much-chinas-economy-has-grown-over-the-last-70-years.html; Simeon Djankov, et al., “The United States Has Been Disengaging from the Global Economy,” Petersen Institute for International Economics, April 19, 2021, https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/united-states-has-been-disengaging-global-economy; Salman Ahmed, et al., “U.S. Foreign Policy for the Middle Class: Perspectives from Ohio,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 10, 2018, https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/12/10/u.s.-foreign-policy-for-middle-class-perspectives-from-ohio-pub-77779; Heather Long, “Alarming Statistics that Show that the U.S. Economy Isn’t As Good As It Seems,” Washington Post, May, 25 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/05/25/the-alarming-statistics-that-show-the-u-s-economy-isnt-as-good-as-it-seems/.

9 “Survey: 79 Million Americans Have Problems with Medical Bills or Debt,” Commonwealth Fund, February 9, 2022, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/survey-79-million-americans-have-problems-medical-bills-or-debt; “Americans’ Views of Problems Facing the Nation,” Pew Research Center, April 15, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/04/15/americans-views-of-the-problems-facing-the-nation/; American Society of Civil Engineers, “2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure,” https://infrastructurereportcard.org/infrastructure-categories/.

10 “E.U.-Russia Relations: Facts and Figures” Council of the European Union, November 23, 2021, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/eu-russia-relations-facts-and-figures/.

11 Lucia Retter, Stephanie Pezard, Stephen Flanagan, Gene Germanovich, Sarah Grand Clement, and Pauline Paille, “See European Strategic Autonomy in Defense,” Rand Corporation, November 2021, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1319-1.html.

12 “Defense Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2021),” NATO Public Diplomacy Division, June 11, 2021, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2021/6/pdf/210611-pr-2021-094-en.pdf. See also Max Bergmann and Siena Cicarelli, “NATO’s Financing Gap,” Center for American Progress, 2021, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/natos-financing-gap/.

13 Lorenz Hemicker, “The Bundeswehr is Plagued by Understaffing and Equipment Shortages, but Policymakers Reject a Significant Budget Increase,” German Times, April 2019, https://www.german-times.com/the-bundeswehr-is-plagued-by-understaffing-and-equipment-shortages-but-policymakers-reject-a-significant-budget-increase/; “German Army Lacks Equipment and Recruits Says Damning Report,” Deutsche Welle, January 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/german-military-lacks-equipment-and-recruits-says-damning-report/a-47281996; Rajan Menon, “The Sorry State of Germany’s Armed Forces,” Foreign Policy, June 18, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/18/trump-withdraw-troops-germany-military-spending/.

14 Jonathan Masters and William Merrow, “How is the U.S. Military Pivoting in Europe?” Council on Foreign Relations, September 23 2020, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/how-us-military-pivoting-europe. The U.S. military presence in Europe has been substantially reduced from the Cold War peak of about 400,000 troops to 70,000, not including the rotational forces, assigned to the European Command.

15 Masters and Merrow, “How is the U.S. Military Pivoting in Europe?”

16 Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defense Itself,” Survival vol. 62 no. 6 (December 2020): 7–34; Posen, “A New Transatlantic Division of Labor Could Save Billions Every Year!” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, September 7, 2021, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2021-09/a-new-transatlantic-division-of-labor-could-save-billions-every-year/.

17 Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself.”

18 For Russia’s GDP relative to Germany’s and France’s combined, see “GDP, PPP (Current International $),” World Bank, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.CD.

19 John Grady, “French President Macron Calls for European ‘Strategic Autonomy,” USNI News, February 8, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/02/08/french-president-macron-calls-for-european-strategic-autonomy.

20 See Anne Applebaum, “The U.S. Is Naïve About Russia, Ukraine Can’t Afford to Be,” Atlantic, January 3, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/01/ukraine-russia-kyiv-putin-bluff/621145/; Ivo Daalder, “Vladimir Putin’s Deepest Fear is the Freedom of Russia’s Neighbors,” Financial Times, January 19, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/6c0c9e21-0cf7-4732-a445-bc117fb5d6f8.

21 See John Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin,” Foreign Affairs (September/October 2014): 77–89.

22 See Robert Wright, “How Cognitive Empathy Could Have Prevented the Ukraine Crisis,” Responsible Statecraft, January 29, 2022, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2022/01/29/how-cognitive-empathy-could-have-prevented-the-ukraine-crisis/.

23 “Remarks of James at the Seeds of Peace Forum on Conflict and Diplomacy, New York, NY,” September 20, 2004, https://www.seedsofpeace.org/remarks-by-james-a-baker-iii-at-the-seeds-of-peace-forum-on-conflict-diplomacy/.

24 “World Development Indicator database” The World Bank, December 1, 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.CD. PPP, rather than exchange-rate-based calculations, are use throughout here because they provide a meaningful basis for comparison when it comes to items such as GDP and defense spending. For an explanation, see Tim Callen, “PPP Versus the Market: Which Weight Matters?” International Monetary Fund, Finance and Development, vol. 44, no. 1 (March 2007), https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2007/03/basics.htm.

25 Siemon T. Wezeman “Russia’s military spending: Frequently Asked Questions,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2020/russias-military-spending-frequently-asked-questions.

26 Eugene Gholz and Harvey Sapolsky, “The Defense Innovation Machine: Why the U.S. Will Remain on the Cutting Edge,” Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 44, no. 6 (2021): 854–72.

27 Caleb Silver, “The Top 25 Economies in the World,” Investopedia, December 22, 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/insights/worlds-top-economies/.

28 Christopher A. Thomas and Xander Wu, “How Global Tech Executives View U.S.-China Tech Competition,” Brookings Insitution, February 25, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/how-global-tech-executives-view-u-s-china-tech-competition/.

29 See Daniel Castro, Michael McLaughlin, and Eline Chivot, “Who is Winning the AI Race: China, the EU, or the United States?” Center for Data Innovation, August 19, 2019, https://datainnovation.org/2019/08/who-is-winning-the-ai-race-china-the-eu-or-the-united-states/; Graham Allison and Eric Schmidt, “Is China Beating the U.S. to AI Supremacy?” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, August 2020, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/china-beating-us-ai-supremacy.

30 Robert Legvold, Return to Cold War (New York, NY: Polity Books, 2016).

31 For the $80 billion estimate, see Barry R. Posen, “A New Transatlantic Division of Labor Could Save Billions Every Year,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, vol. 75, no. 5 (2021): 239–243.

32 On intra-EU trade, see “Intra-EU Trade in Goods—Main Features,” Eurostat, April 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Intra-EU_trade_in_goods_-_main_features#Intra-EU_trade_in_goods_by_Member_State.

33 “Biden Orders Another 3,000 Troops to Deploy in NATO Ally Poland,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, February 11, 2022, https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-biden-3000-troops-poland/31699690.html.