On November 14, aerospace company SpaceX is slated to launch humans on the first operational mission to the International Space Station, ending nine years of NASA’s reliance on Russia to launch U.S. astronauts into space. But a mere 14 years ago, on a tiny Pacific atoll in the Marshall Islands, the upstart outfit was just trying to get off the ground.

Founded in 2002 by tech entrepreneur Elon Musk, SpaceX was initially operating from a former U.S. government launch facility on Omelek Island, where the proximity to the Equator—the region of Earth that spins fastest—gives rockets a boost up into orbit. While the unproven company was well positioned geographically, it was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

In 2006, during SpaceX’s first launch attempt on Omelek, a Falcon 1 rocket carrying a U.S. Air Force Academy satellite experienced an engine failure about 30 seconds after liftoff, sending the rocket careening into the ocean and the satellite crashing into a storage shed on the island.

A year later, a Falcon 1 carrying a dummy payload spun out of control just before reaching orbit. The third attempt in August 2008, with a Falcon 1 carrying two small satellites for NASA and one for the Department of Defense (as well as cremated remains of astronaut Gordon Cooper and Star Trek actor James Doohan), ended in a fiery failure when two parts of the rocket, known as the first and second stage, crashed into each other after they separated.

The fourth time was finally the charm: Just eight weeks after their third failure and once again carrying a dummy payload, the successful launch of a Falcon 1 from Omelek Island made SpaceX the first company to send a privately funded liquid-fueled rocket into orbit.

Back in 2008, no one could have envisioned what the brash aerospace company would go on to accomplish. SpaceX has since become the first—and for now, the only—company to fly humans into orbit on its own spacecraft. But getting to that point has been a long road, punctuated by historic firsts, spectacular failures, and a stream of controversy surrounding the company’s founder Elon Musk.

An early bet

Since those early days on Omelek Island, SpaceX has chalked up a number of records. It became the first company to launch a resupply mission to the ISS in 2012. Three years later, it landed the first stage of an orbital rocket for the first time in history. The company now operates the most powerful rocket in the world, Falcon Heavy, and last year it launched 13 of the 21 U.S. flights to orbit.

SpaceX, however, never would have gotten to where it is today without NASA. In 2006, before SpaceX had ever flown a rocket, NASA awarded the aerospace firm a contract under the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program, ultimately injecting $396 million into the company as it developed the Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 rocket—a significantly more powerful successor to the Falcon 1, with nine first-stage engines rather than one.

“Mike Griffin, the [NASA] administrator at the time who really conceived of the COTS program, at one point characterized it as a gamble,” recalls Phil McAlister, NASA’s director of commercial spaceflight. At the time, the space agency was primarily focused on the Constellation Program, a major effort under President George W. Bush’s administration to build new vehicles and return to the moon. But the head of NASA was willing to invest in commercial spaceflight as a “side bet,” McAlister says.

“COTS, I would say, was the first major effort to do things in a really non-traditional way,” he adds.

During the first round of COTS funding in 2006, 20 aerospace companies submitted proposals, but only SpaceX and another start-up—Rocketplane Kistler, which had its funding pulled after it failed to meet deadlines—were selected for the program. In a second round of COTS funding in 2008, NASA selected the company Orbital Sciences (now owned by Northrop Grumman) from about a dozen proposals, and the company received $288 million to develop its Cygnus spacecraft and Antares rocket, which have been successfully delivering cargo to the ISS since 2013.

As SpaceX and Orbital Sciences worked on their new space vehicles, it became apparent to NASA that commercial spaceflight was no longer a side bet—the space shuttle was set to retire in 2011, and the Constellation Program was canceled by the Obama Administration. If the United States was going to have a way to resupply the ISS, it needed to come from private industry.

In 2008, three months after SpaceX’s first successful flight from Omelek Island, NASA awarded the first Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contracts, valued at $1.9 billion for Orbital Sciences and $1.6 billion for SpaceX to carry cargo to the ISS.

“We weren’t even done with development” of the new vehicles, McAlister says. “We realized that we needed these capabilities early, so I think we let the CRS contract [proceed] a little bit earlier than our normal plan was.”

NASA hands over the reins

As SpaceX and Orbital Sciences made progress toward launching resupply missions, NASA began to seriously consider whether companies were capable of launching not just cargo, but humans. In a major milestone in 2009, before a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket had ever flown, a committee on human spaceflight ordered by the Obama Administration concluded that “commercial services to deliver crew to low-Earth orbit are within reach.”

Two years later, the Commercial Crew Program (CCP) was announced, which ultimately led to SpaceX and another commercial outfit, Boeing, being awarded $2.6 billion and $4.2 billion, respectively, for the human-rated Crew Dragon and CST-100 Starliner spacecraft.

But handing over human spaceflight responsibilities would not be easy. Launching people “had been done a particular way since NASA was born,” McAlister says. “Since the beginning of the space age, we had been making these decisions, we had shouldered this responsibility.”

The losses of the space shuttles Challenger and Columbia and the 14 astronauts on board underscored the consequences of mistakes in human spaceflight. “We felt like that became part of our DNA as well, having to live through that,” McAlister adds. Trusting human spaceflight to private companies “was a contentious debate that we had, not only within NASA, but with our stakeholder community in the [Obama] Administration, in Congress, and in the public."

Part of the reservation was that SpaceX represented a new kind of culture in spaceflight—a more brazen approach that terrified some at NASA, but that others found refreshing.

Before the first flight of the Falcon 9 rocket in 2010, for instance, SpaceX used a blow dryer to dry out the rocket’s electronics after a storm doused them in water, according to an article in Ars Technica by Eric Berger. On the next Falcon 9 flight, Musk had an engineer cut six inches off the bottom of a rocket nozzle with metal shears after an engine crack was discovered.

“SpaceX reflects, to a significant degree, the personality of Elon Musk, which is kind of swashbuckling,” says John Logsdon, a space historian and professor emeritus at George Washington University. “But they’ve shown lots of engineering flexibility and engineering smarts in their approach to doing things.”

“SpaceX is one of these sort of Google/Facebook-type companies because of the types of people that are working there, and there’s a huge generational shift,” says Jennifer Levasseur, a curator and historian at the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum. “It is not a nine-to-five job like you might experience at some other place. It is all-encompassing. Everybody’s all-in to making this thing work.”

That cavalier, breakneck culture encouraged by Musk may have helped the company make quick strides in aerospace technology, but it has also led to lawsuits with former employees, spats with NASA, and even a formal review of SpaceX’s workplace culture after Musk smoked cannabis during an interview on a popular podcast.

“The people at [NASA’s] Johnson Space Center were very comfortable working with Boeing,” Logsdon says. “They’ve had to learn to work with SpaceX.”

Willing to fail

On its path to launching humans through NASA’s commercial crew program, SpaceX has not been immune from incidents. In 2015, one of its rockets broke apart during liftoff, destroying a cargo spacecraft bound for the ISS. The following year a Falcon 9 rocket exploded on the pad during a fueling test, incinerating the Israeli communications satellite on board and raising concerns about SpaceX’s plan to load fuel onto a rocket once astronauts had already boarded.

But after each incident, SpaceX was able to identify the cause and convince NASA that they had solved the problem. “It can’t just be about the accident or the failure—it has to be about how you recover from it,” Levasseur says. “Each time, they’ve obviously been able to assure NASA that the recovery is going to mitigate as a concern whatever may have failed the last time.”

Boeing has also experienced setbacks on its road to launching humans—most recently in December 2019, when an uncrewed test flight of its Starliner spacecraft failed to fire its thrusters to reach the correct orbit and rendezvous with the ISS. Boeing plans to launch another uncrewed test flight of the spacecraft in late 2020 or early 2021, and if that flight goes well, it could launch humans on Starliner for the first time in mid-2021.

But for now, SpaceX is the only way to get to the ISS from the U.S. Its Falcon 9 has become one of the most reliable rockets ever built. The company has successfully landed a Falcon 9 first stage 57 times and counting—allowing it to reuse the largest part of the rocket as well as its nine primary engines. The same Falcon 9 first stage has flown up to six times, and SpaceX plans to reuse these rocket boosters 10 times before retiring them.

“You got to give credit where credit’s due,” McAlister says. “SpaceX really pushed the envelope associated with reusability.”

To get to the point where it could land an orbital rocket, SpaceX has had to crash several, letting the boosters explode in public view as the company gathered the necessary flight data to finally pull off a landing in 2015. This approach is again on display as SpaceX develops its new rocket, Starship, and the company destroys prototypes in testing as it works out the kinks in the vehicle’s design.

That willingness “to put something out there and have it fail … is much different than the prior models we’ve seen” to develop a spacecraft, Levasseur says. And this generational shift in attitude, she says, can be seen in the pop culture inspirations behind SpaceX, including the Falcon 9 rocket named for Han Solo's Millennium Falcon. “We’ve moved from the Buck Rodgers and Flash Gordon types to the Star Trek and Star Wars people.”

Despite initial reservations, the new approach seems to be working. SpaceX’s success is highlighted by the recent NASA certification of Crew Dragon—the first human-rated spacecraft to receive NASA approval since the space shuttle nearly 40 years ago. The swashbuckling, blow-drying, rocket-crashing SpaceX is now set to reestablish the United States’ space independence.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

-

This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

-

Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

-

When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

-

Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

-

This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

-

This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

-

Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

-

This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

-

U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

-

Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

-

Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

-

Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

-

Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

-

The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

-

Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

-

Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

-

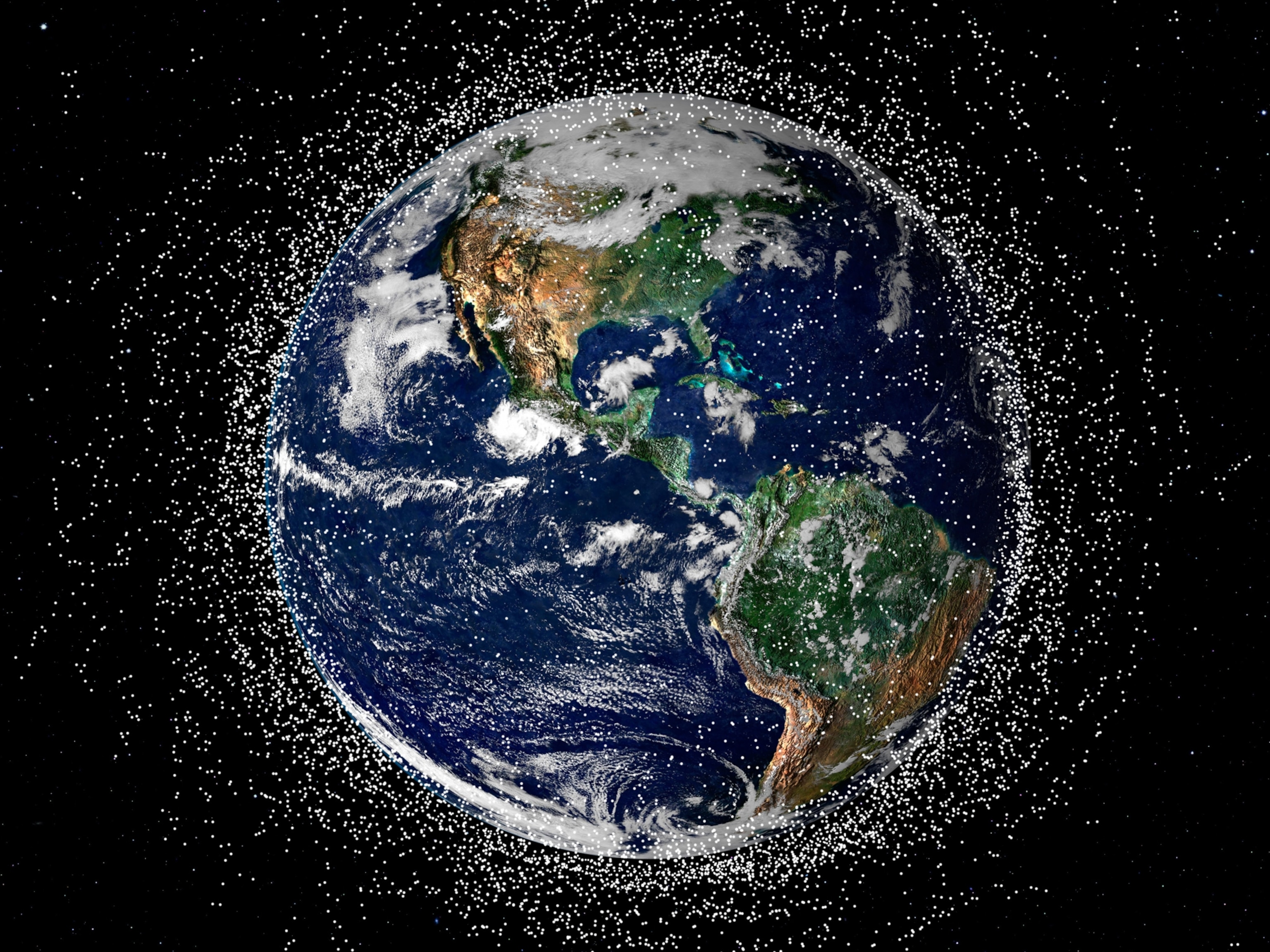

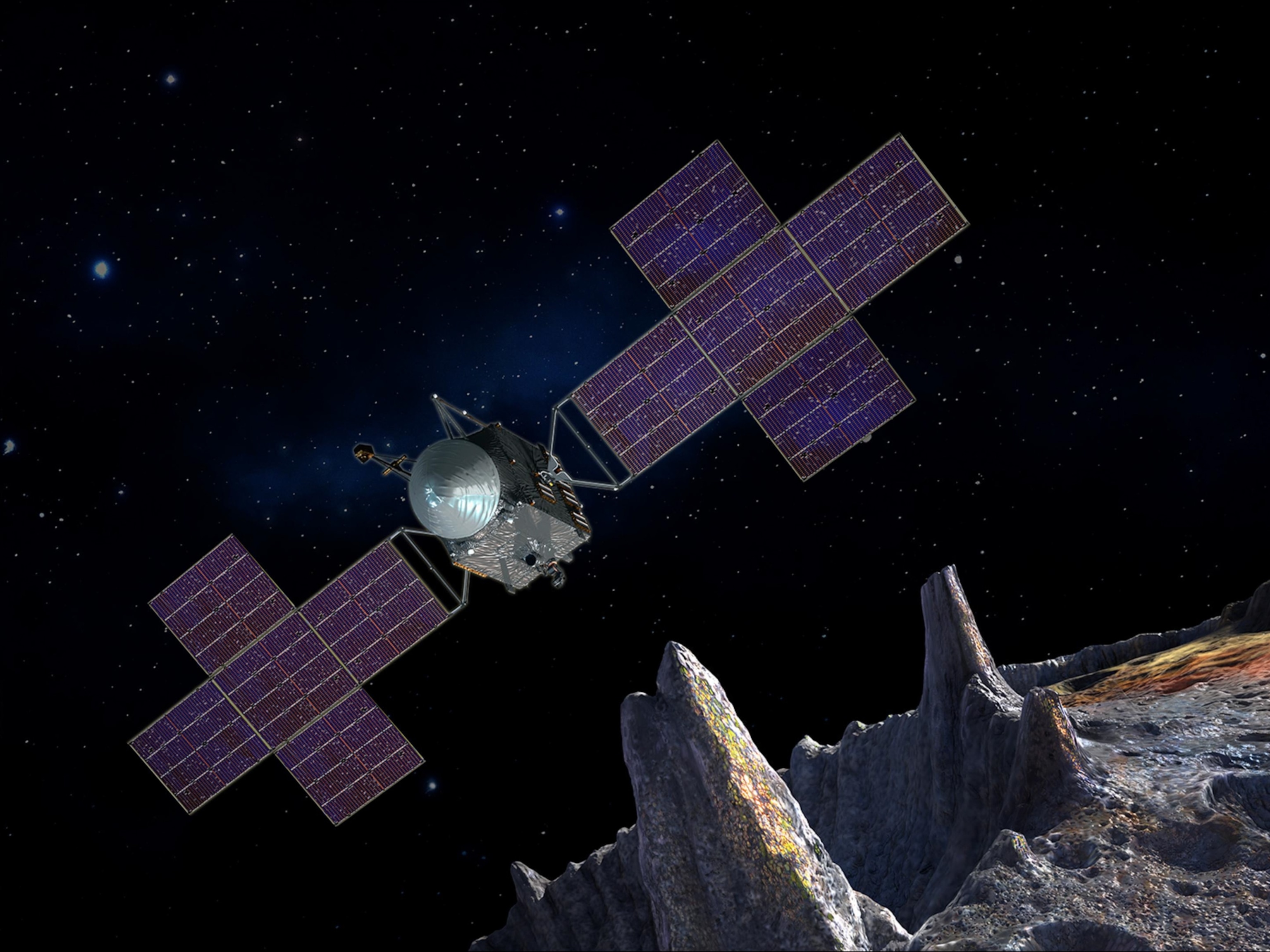

NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

-

Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

-

What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

-

Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

-

This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

-

Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest