State laws dictate the formal organization of the Democratic party in Texas and provide for both temporary and permanent organs. The temporary party organs consist of a series of regularly scheduled (biennial) conventions beginning at the precinct level and limited to persons who voted in the party primary. The chief function of the precinct convention is to choose delegates to the county convention or the senatorial district convention held on the third Saturday after the first primary. When a county has more than one senatorial district because of its large population, a separate senatorial district convention is held for each senate district in the county. The delegates who gather at the county and the senatorial district conventions are likewise chiefly concerned with choosing delegates to the state convention held biennially in June for the purpose of formally choosing the state executive committee, adopting a party platform, and officially certifying the party's candidates to be listed on the general election ballot. In presidential election years the state convention also chooses delegates to the national presidential nominating convention. Until 1984 two state conventions were held in gubernatorial years, one for state affairs in September and one for sending delegates to the national Democratic convention. The permanent organs of the party are largely independent of the temporary ones. Voters in the Democratic primary in each precinct elect for a two-year term of office a chairman or committee person who is formally the party's agent or spokesman in that precinct. A few of these precinct chairmen work diligently for the party and its nominees; some do very little. Normally the precinct chairman will be in charge of the conduct of the primary in his precinct, and, perhaps less assuredly, will serve as chairman of the precinct convention and of the delegation to the county convention. The party's county executive committee consists of the precinct chairmen plus a county chairman who is elected in the primary by the Democratic voters in the county as a whole. The county committee determines policy in such matters as the conduct and financing of the primary, and officially canvasses its results. It also serves as a focal point for party organizing and campaigning efforts.

The State Democratic Executive Committee includes one man and one woman from each of the thirty-one state senatorial districts, plus a chairman and a vice-chairman, formally chosen by the state convention but informally chosen by a caucus of the delegates from each senatorial district. Occasionally a governor and his advisers will decide that a caucus nominee is simply unacceptable and then will substitute his own choices. By law the state committee is responsible for overseeing the party primary and for canvassing the returns. It also undertakes fund-raising and campaign work for the party. Before Republican Bill Clements' election as governor in 1978, the committee's role was to serve as an adjunct of the governor's office, designed to help the governor as best as it could with political and policy problems. However, after Clements was elected, the party and its machinery developed a new degree of independence from the governor.

The Democratic party has played a central role in the political development of Texas since White Americans first settled the region. The majority of early settlers came from the American South and brought their past political allegiances with them. Texas Democrats evolved over the years from a very loose association into an organized party. This evolution was slow because the lack of a second party in Texas throughout much of the state's history caused Democrats to be less concerned with developing a unified, centralized party organization and more inclined to engage in factional strife. Throughout much of its existence, the Democratic party has been protective of the status quo.

The history of the party in Texas can be divided into two major periods. In the first period, from independence in 1836 through the presidential election of 1952, the Democratic party in Texas was the only viable party in the state. It dominated politics at all levels. In the second major period, after 1952, the party faced a growing challenge to its control of state affairs from the once ineffective Republican party. Both of the major periods, however, can be subdivided. The years 1836 through 1952 divide into six subsections: from independence in 1836 through the Civil War, Reconstruction, the late 19th Century, the Progressive Era, the 1920s, and the New Deal-World War II era. The latter period divides into three subsections: the 1950s, the 1960s, and the 1970s and 1980s.

Several crucial events marked the years 1836 through 1865 in Texas political history, including the independent nationhood of the Republic of Texas, entrance into the Union, and secession and the Civil War. During these years the Democratic party officially formed in Texas. As a result, the party in the state was both affected by these events and was a major actor in this period. Even before Texas gained its independence from Mexico the Democratic party in the United States influenced the politics of the region. As early as February 25, 1822, with the formation of the Texas Association in Russellville, Kentucky, individuals interested in land speculation came together to secure land grants in Texas. The Texas Association drew its membership from professionals-merchants, doctors, and lawyers-in Kentucky and Tennessee. Many of these men were also close friends of Andrew Jackson and had strong ties to the Democratic party. Likewise, most of the settlers in Texas were either from the Upper South or the Lower South and held strong allegiances to the Democratic party. Elections in the Republic of Texas demonstrated competition among rival factions or strong individuals. Despite sympathy for the Democratic party in the United States, as yet there was no strong party tradition in the Republic of Texas. Before 1848, elections in Texas were conducted without organized political parties. Personality was the dominant political force in the state. Contests between factions evolved into a more defined stage of competition with the development of the Democratic party in Texas as a formal organ of the electoral process during the 1848 presidential campaign. Even so, it was some time before Democrats adopted any sort of a statewide network or arranged for scheduled conventions.

Nevertheless, between annexation and 1861 partisanship developed slowly but steadily. Men who governed the state generally reflected the views of the burgeoning Democratic party. However, personal loyalty such as that found in the factions supporting and opposing Governor Sam Houston (1859–61) still heavily influenced state politics. Competition for the Democrats came from various sources at different times and included first the Whig party, then the American (Know-Nothing) party, and finally the Opposition or Constitutional Union party. The mid-1850s witnessed rapid growth of the formal mechanisms of party discipline. For example, delegations from twelve counties attended the state Democratic convention in 1855, yet the following year, with the Know-Nothing threat still seemingly viable, more than 90 percent of Texas counties were represented. During these years the convention system became the chief method of recruiting candidates for office in the Texas Democratic party. In the years after 1854 the ongoing upheaval in national politics influenced the party. In the process Texans moved away from an earlier identification with Jacksonian nationalism and became closely associated with the states'-rights goals of the lower South. Yet the election of Houston as governor in 1859 demonstrated the divisions within the state's political structure, since he represented the Opposition in the contest against the Texas Democratic party. During the Civil War, the Democratic party in Texas became closely associated with the extreme proslavery wing of the Democratic party in the Confederacy, and partisan activity came to a halt.

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, during the period of presidential Reconstruction, the split between Unionist and Secessionist Democrats reemerged. During the war the strongest Unionists had disappeared from the political scene or had moved north. Those who stayed active reluctantly supported the Confederacy. After the war the Unionists continued to support a more egalitarian distribution of power in the state, while working to reduce the influence of former planters. But they split also. Their positions on freedmen ranged from supporting full civil and political rights to opposing anything beyond emancipation. In part as a result of the split among Democrats but more as a result of congressional Reconstruction nationally, Republicans captured both the governor's office and the state legislature in 1869. By 1872 Democrats regrouped and overturned the Republican government in the Texas legislature, charging that the administration of Governor Edmund J. Davis (1870–74) was corrupt and extravagant. Much of the money appropriated during Republican control had in fact gone to frontier defense, law enforcement, and education. Davis had two more years in office, but he could do little with a Democratic legislature pledged to austerity. In the gubernatorial election of 1873, the Democratic campaign theme included support for states' rights, loyalty to the Confederacy, and an attack on freedmen and Republicans. The final Democratic measure to overturn all Republican influence in Texas came with the passage of the Constitution of 1876, which severely constrained the powers of the state government, cut back on state services and limited the amount of money that could be raised in taxes.

The Democrats' return to power at the end of the Reconstruction era did not mean an end to factional divisions within the state. Like the rest of the nation, Texas faced various third-party challenges during the Gilded Age, a fact that reflected a growing uncertainty about economic conditions. In 1876, however, the state Democratic party continued to focus its attention on the concerns of the Civil War era. In fact, the majority of the delegates to the state Democratic convention were Confederate veterans. Democratic voters were often White landowning agrarians, manufacturers, lumbermen, bankers, shippers and railroad men, and Protestants. Indeed the conservative political moods of the state through the late 1880s can be attributed to the growing cult of the Confederacy throughout the South. Against this backdrop a vote against the Democratic party became a vote against the cultural legacy of the "Lost Cause." Party organization also encouraged more Southern loyalist candidates through the convention process. After 1878 Texas Democrats had trouble adjusting to the various third-party challenges of the late nineteenth century, as demonstrated by conflicting responses to the Greenback movement (see GREENBACK PARTY). At times Democrats endorsed even more drastic inflationary measures, but at other times they bitterly attacked financial views that encouraged printing of additional paper money. In the end the Greenback challenge forced Texas Democrats to pay attention to the economic problems of the state. By the 1880s the issue of prohibition also began to cause problems for Texas Democrats, who initially sought to dodge the question by calling for local-option elections. Nevertheless, prohibition politics evenly split the party and laid the ground for bigger battles in the early twentieth century.

In the 1880s and 1890s Texas Democrats faced an even bigger challenge, first from the Farmers' Alliance and then from the People's (Populist) party. Maintaining an official posture apart from organized politics, the Farmers' Alliance sometimes worked with the state Democratic party. By the late 1880s Texas Democrats recognized the agrarianists' demands and adopted a platform supporting the abolition of national banks, issuance of United States currency, and the regulation of freight rates and businesses. The election of James Stephen Hogg as governor in 1890 temporarily allied the agrarian protest with the Democratic party. Hogg's efforts on behalf of the newly constituted Railroad Commission divided the Democratic party into three factions: businessmen who sought to limit the commission's impact, leaders of the Farmers' Alliance who sought to dominate the commission, and farmers, businessmen, and politicians who supported Hogg. Alliancemen soon split further away from Hogg and the majority of Texas Democrats over the idea of subtreasuries. By the 1890s Texas Democrats had given their support to silver coinage. In the years after 1896 most Populists in Texas returned to the Democratic party because Democrats had incorporated portions of the Populist platform and economic conditions for farmers had improved, while segregationism discouraged economic cooperation with African Americans.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century the party split into a progressive wing that increasingly identified with the demands of prohibitionists and a stand-pat wing opposed to progressivism. The reality of one-party politics in Texas and the South paved the way for factional splits, such as the one over the prohibition issue during the first third of the twentieth century. Personality also played a key role in the split in the Democratic party when the progressive forces within the party banded together to squelch the influence of United States senator Joseph Weldon Bailey in state politics. The "Bailey question" became associated with the perceived evils of corporate power and swollen private interests in the public domain. Yet reforms during the 1890s and early 1900s had reduced the influence of railroads, out-of-state corporations, and insurance companies in state politics, leaving moral and cultural problems to consume the attention of Progressive Era reformers. During the presidential election of 1912 a common thread connecting the progressive Democrats supporting Woodrow Wilson and the advocates of prohibition became apparent. In the immediate aftermath of Wilson's election Texas Democrats-including Albert S. Burleson, Thomas Watt Gregory, Edward M. House, David F. Houston, and Morris Sheppard established an important precedent for Texas Democrats by taking a significant role in national political affairs that continued throughout most of the twentieth century. In 1914 personality again ruptured the Democratic party in Texas with the election of James E. Ferguson as governor. Ferguson sought to avoid the liquor question entirely, although his sympathies and his big contributors were wet. His official actions as governor, including an ongoing battle with the state's cultural and intellectual elite at the University of Texas, eventually united progressive Democrats in their opposition to him. After Ferguson was impeached, dry, progressive Democrats aligned with the new governor, William P. Hobby, Sr. (1917–21), and enacted their agenda of liquor reform, woman suffrage, and reform of the election laws.

For Texas Democrats the decade of the 1920s was a bridge between the ethnocultural issues of the Progressive Era and the economic concerns of the Great Depression and the New Deal. During World War I, Texas Democrats had addressed many issues of the Progressive Era and found legislative solutions, leaving Texans to argue over the results of prohibition for the next decade. But Texas Democrats, like their counterparts throughout the South, soon shifted their goals for reform away from a social and cultural agenda toward what can best be described as business progressivism, or an increased concern for expansion and efficiency in government. Yet they did not limit their attention to issues such as highway development, economic growth, and education improvement, but also joined numerous intraparty battles revolving around the enforcement of prohibition, the Ku Klux Klan, and "Fergusonism." Despite Pat Neff's gubernatorial administration (1921–25) and its attention to the cause of business progressivism with such measures as government consolidation, prison reform, education reform, highway construction, and industrial expansion, the legislature was not willing to accept all of Neff's ideas. The result was a mixed record on business progressivism. The state elections in 1924 quickly evolved into a fight over the Klan issue. Furthermore, the presence of Ma (Miriam A.) Ferguson as the leading anti-Klan candidate further weakened the progressive Democratic forces in the state. However, electing Mrs. Ferguson did have one ameliorative affect on Texas politics, namely the elimination of the Klan as a political force. The other major political development in Texas during the 1920s centered around the 1928 presidential election. In Texas, as in the rest of the nation, the contest served to heighten the tensions between wet and dry Democrats. In the fall of 1927 several young Democrats who opposed prohibition organized to fight the entrenched dry progressive wing of the state Democratic party and to work for an uninstructed delegation to the national convention that eventually endorsed Al Smith. They regarded Governor Dan (Daniel J.) Moody (1927–31) as their leader. The selection of Houston as the host city for the Democratic national convention further enlivened Texas politics as Smith's backers and the bone-dry forces maneuvered for control of the state's delegation and Moody's support.

In the spring of 1928 the dry progressive Democrats formed the Texas Constitutional Democrats to gain control of the state's party machinery and to work for a presidential ticket that reflected their views. Governor Moody led a third group, the Democrats of Texas or the Harmony Democrats, that eventually organized to prevent a bitter feud between the warring factions of the party and to try to develop a common program. These factional divisions within the party resulted in a bitter division both among delegates at the Houston convention and within the state Democratic party. Some of the state's most ardent Democratic supporters of prohibition put principles above party and worked for the Republican nominee Herbert Hoover in the general election rather than support the Catholic wet candidate, Al Smith. The Klan faction of the Democratic party, although waning in influence, also informally supported Hoover. Dry voters in rural North and West Texas and urban voters influenced by the Klan and Republican prosperity in Harris, Dallas, and Tarrant counties account for most of the Democrats who went with Hoover. The Republicans also did well among fundamentalists. Hoover was the first Republican presidential nominee to carry Texas, but it was all for naught. The depression, the New Deal, and World War II put Republican ascendancy in Texas on hold for twenty-four years.

Economic crisis followed by recovery dominated the period 1932–1952 in Texas politics. The early New Deal years yielded a period of political harmony within the state's Democratic party, but by the late 1930s conservative forces had regrouped and regained control of state politics. At the same time liberal factions began to exert pressures on the political process that did not subside for the remainder of the twentieth century. In the years immediately following the stock-market crash in 1929, controversies surrounding the oil and gas industry, the agricultural depression, the return of Fergusonism, and the rapid passage of New Deal legislation that overshadowed state and local efforts to combat the depression paralyzed state government and the Democratic party in Texas. At the same time, Texas Democrats in Washington, including Jesse H. Jones, John Nance Garner, Tom (Thomas T.) Connally, Marvin Jones, James P. Buchanan, Hatton W. Sumners, J. W. Wright Patman, and Sam (Samuel T.) Rayburn, exerted significant influence after the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. By the mid-1930s the depression became the single most important issue in state politics. As yet, little conservative opposition to New Deal reforms had coalesced in Texas. In 1934 Texas voters elected James Allred governor. His administration attempted to deal with the impact of the depression on the state by reorganizing state law enforcement, putting a state tax on chain stores, increasing assistance to the elderly, starting a teachers' retirement system, and increasing funding to public schools. Allred's advocacy of these measures earned him the respect and admiration of the liberal wing of the state Democratic party.

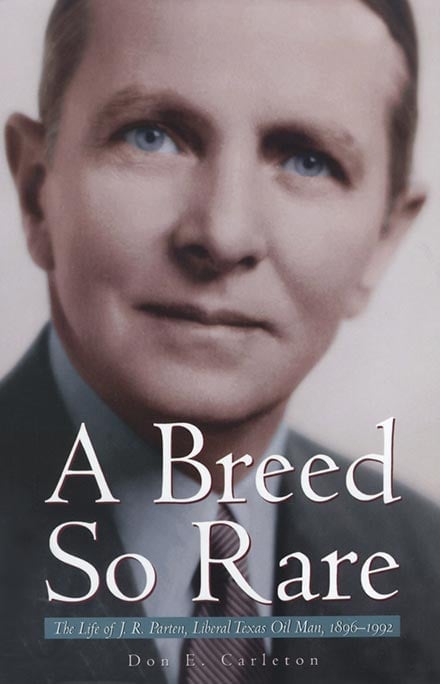

By 1936 conservative reaction to the national Democratic party erupted in the formation of the Jeffersonian Democrats. This national organization received significant aid from several prominent conservative Texas Democrats including John Henry Kirby, Joseph Weldon Bailey, Jr., and J. Evetts Haley. Though the Jeffersonian Democrats had little impact on the 1936 election, they did foreshadow political trends of the 1940s and 1950s. Indeed the election of W. Lee "Pappy" O'Daniel as governor in 1938 signaled the return to power of the conservative wing of the Democratic party in Texas. Though O'Daniel's campaign rhetoric appealed to impoverished Texans still suffering the effects of the depression, his financial supporters and policy advisors were generally drawn from the state's business and financial leaders. The battle over a third term for Roosevelt also divided the party. When many Texas Democrats encouraged the unsuccessful presidential candidacy of Vice President John Nance Garner, the party split between Garner Democrats, including many of the old Jeffersonian Democrats, and the New Deal Democrats. The 1940 fissure remained throughout the coming decade as conservatives and liberals fought for control of the party. But attention to foreign policy during World War II temporarily slowed the battles between the warring factions.

The politics of race, however, renewed tensions within Texas when the Supreme Court overturned the state's white primary law in the case of Smith v. Allwright (1944). The success of the white primary as a method of controlling access to the ballot box was closely tied to the fortunes of the Democratic party. The device went through several changes throughout its existence, but it relied heavily on a solid Democratic dominance that made a Democratic primary victory tantamount to election. In 1927 in Nixon v. Herndon the United States Supreme Court had struck down a Texas law preventing Blacks from voting in the Democratic primary (see NIXON, LAWRENCE AARON). The Texas legislature then authorized the Democratic State Committee to exclude Blacks, and, when the Supreme Court overturned this law in Nixon v. Condon in 1932, Texas repealed the law and left control of the primary entirely with the Democratic party. Since no state action was now involved in the committee's decision to exclude Blacks from the Democratic primary, in 1935 the court held the new Texas arrangement valid in Grovey v. Townsend (see GROVEY, RICHARD RANDOLPH). Then came Smith v. Allwright. Though it initially opposed the decision, the Texas Democratic party came to rely on Black voters.

More important at the time, however, the presidential election of 1944 heightened tensions between the Roosevelt and anti-Roosevelt wings of the party. FDR's renomination for a fourth term led conservative Texas Democrats to join with the American Democratic National Committee, an organization formed to defeat the president. Texas conservatives received support from the same individuals who had aided the Jeffersonian Democrats a decade earlier. Wealthy Texas conservatives with an interest in the increasingly powerful oil and gas industry funded the conservatives, who controlled about two-thirds of the delegates to the state Democratic convention in May 1944. National convention delegates from Texas thus supported the conservative anti-New Dealers, but angry liberals rejected the actions of the state convention and sent their own delegation to the national convention. The New Deal Democrats in Texas barely regained control of the state party's machinery at the governor's convention in September. However, conservative Texas Democrats organized into the Texas Regulars and arranged for the placement on the November ballot of an independent slate of electors who would never vote for FDR. The Texas Regulars received less than 15 percent of the state vote; they and their conservative backers learned that a strong voice in state politics would not translate directly into influence on national politics. Despite the persistent loyalty of the majority of the state's voters to the Democratic party, the widening schism between the factions indicated that a growing number of Texans were receptive to more conservative politics both within and outside the traditional Democratic party. Indeed actions including the appointment of conservative businessmen to state boards and commissions and the passage of a right-to-work law that Texas governors, all Democrats, implemented during the 1940s reflected the dominant conservatism of the state.

The 1948 Senate race in Texas exemplified many of the tensions within the state party. Lyndon B. Johnson, who eventually defeated Coke Stevenson in an election fraught with charges of wrongdoing on both sides, represented the difficulties liberal New Dealers faced when they attempted to campaign statewide. To appeal to a conservative but Democratic electorate required pragmatic compromise. By the end of the 1940s the Democratic party in Texas had split at least three ways-into a conservative wing that usually controlled state politics, a liberal wing that had supported the New Deal and that later championed the rights of women, the working class, and ethnic minorities, and a group in the middle that shifted back and forth between the two extremes. By the middle twentieth century the Texas Democratic party was riven by factional strife. The liberal-conservative Democratic split also aided the development of a viable state Republican opposition. In the years after the 1952 presidential election a two-party system began to emerge. The gubernatorial administration of R. Allan Shivers (1949–57) and the efforts of the liberal opposition to reclaim power within both the state party machinery and the state government dominated state Democratic politics during the 1950s. During the 1950s Texas Democrats also wielded significant power in Washington with Sam Rayburn as speaker of the House and Lyndon Johnson as Senate majority leader. Texas Democrats Oveta Culp Hobby and Robert Anderson held cabinet appointments during the Eisenhower administration. After becoming governor, Shivers took control of the party machinery by instituting a purge of the State Democratic Executive Committee, an organization with two members from each state Senate district, and stacking its membership with his supporters. Shivers also engineered a change in the election laws that permitted cross-filing for both the Democratic and Republican primaries in the 1952 election. As a result of the change, conservative Democrats, termed "Shivercrats" because of their allegiance to the governor, also filed in the Republican primary, thus reducing the number of Republicans that ran for office.

The ongoing struggle with the federal government over control of the Texas Tidelands further complicated the 1952 election in the state. Though federal ownership of the submerged oil-rich lands would benefit Texas in terms of royalty payments, oil and gas interests in the state stood to profit more if the state retained possession of the Tidelands. Conservative Democrats took the lead in championing native interests, which were backed by most Texans as well. Liberal and moderate Democratic politicians, who had stronger ties to the administration of President Harry S. Truman and the national Democratic party, found themselves in a more precarious position and either carefully balanced their support for Texas ownership of the Tidelands with the larger national interests or opposed Texas ownership altogether (see TIDELANDS CONTROVERSY).

Following the triumphs of Eisenhower and Shivers in 1952, liberals in the Texas Democratic party decided to organize and increase their influence on party politics. In May 1953 the short-lived Texas Democratic Organizing Committee was formed. By January of 1954 this group became part of the newly constituted Democratic Advisory Council. The DAC participated in Texas politics for two years before the Democrats of Texas organized in 1956. The DOT, the most successful of the three groups, lasted through 1960 before disbanding. Each of these groups received support from the liberal weekly journal of political information, the State Observer and its 1954 successor, the Texas Observer. Each of these liberal organizations also received support from labor and a number of women activists. The goals of the groups focused on taking control of the official machinery of the Texas Democratic party away from the Shivers forces. In 1956 Johnson and Rayburn battled Shivers, the nominally Democratic governor who had helped deliver the state's votes to Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952, for control of the Democratic party machinery. Three main groups-the Shivercrats or conservative Democrats, moderate Democratic backers of LBJ, and the liberals-engaged in this intraparty battle that featured mistrust, mudslinging, shifting alliances, and ultimately a deeper division within the party. The Republicans, with the help of Shivers, managed to carry Texas for Eisenhower again in 1956. The following year liberal Democrats in Texas fought back against the strength of the Shivercrats, and Ralph Yarborough's narrow victory in the 1957 special United States Senate race gave the liberal wing of the Texas Democratic party a new elected voice in national politics.

Factional infighting in the Democratic party declined during the 1960s. First Johnson's presidential ambitions and then his presidency dominated Texas politics in that decade. In 1959 the state legislature authorized a measure moving the Democratic primary from July to May and permitting candidates to run simultaneously for two offices, thus allowing Johnson to run for the Senate and the presidency. (This measure, dubbed the LBJ law, also benefited Lloyd Bentsen's dual run for the vice-presidency and the Senate in 1988.) Despite efforts by the Democrats of Texas to secure the support of state convention delegates and power within the party machinery, conservative Democrats retained control. Through the work of LBJ and the Viva Kennedy-Viva Johnson clubs, the Democrats narrowly carried Texas in 1960, reversing the direction of the 1952 and 1956 presidential elections in Texas. Similarly, the 1961 special election to fill Johnson's Senate seat had a lasting effect on Democratic party organization in Texas. After Yarborough's unexpected victory in the 1957 special election, conservative Democrats in the state legislature amended the election laws to require a run-off in special elections when no candidate received at least 50 percent plus one vote. In 1961, within a field of seventy-two candidates, three individuals made a strong claim for the liberal vote, thus dividing liberal strength and opening the way for a runoff between William A. Blakley, the interim senator and a conservative Texas Democrat, and John G. Tower, the only viable Republican candidate in the race. Liberal Democrats thought Blakley as conservative as Tower and opted either to "go fishing" during the run-off or support Tower, thinking it would be easier to oust him in 1966 with a more liberal Democratic challenger. Tower, however, easily won his next two reelection bids and eked out a third in 1978. Liberals also hoped that a Republican victory would encourage the development of an effective Republican party in the state and allow moderates and liberals to gain control of the state Democratic party. Indeed, Texas Democrats statewide remained divided between liberals who supported Ralph Yarborough and moderates who backed LBJ. The two factions waged war over the gubernatorial contest in 1962, when John B. Connally, a moderate to conservative Democrat associated with the Johnson wing of the party, was elected. As governor, Connally concentrated his efforts on economic development but received criticism from liberals who thought he neglected minorities and the poor. The Kennedy assassination on November 22, 1963, which traumatized the citizens of Texas, also deeply shook the state Democratic party since it propelled Johnson into the White House and created the need for a greater degree of accommodation between moderate and liberal Texas Democrats. In the 1964 presidential race Johnson carried his home state with ease. In the middle to late 1960s, however, Connally's iron rule of the State Democratic Executive Committee further weakened the liberal forces within the state Democratic party. The results of the 1968 presidential election in Texas also emphasized the sagging fortunes of the Democratic party in Texas, as Hubert Humphrey barely managed to carry the state.

Liberals in the Texas Democratic party reached a low point in 1970 with the defeat of their spiritual leader, Ralph Yarborough, in the Democratic primary by conservative Democrat Lloyd Bentsen, Jr. Bentsen successfully employed a strategy that conservative Democrats in Texas later used against the increasingly viable Republican party, namely, developing a base of support among middle to upper income voters in the primaries, then drawing from the traditional Democratic constituencies of lower income people, labor unions, and minorities in the general elections. The 1972 gubernatorial election marked the culmination of a gradual transition in Texas Democratic party politics from an era when elite leaders fighting behind closed doors over a conservative or liberal agenda dominated party politics to an era of moderation and greater toleration for diverse views. This contest took place against the backdrop of the Sharpstown Stock Fraud Scandal in the Texas state legislature. The scandal ended the political careers of Governor Preston Smith, Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes, and Speaker of the House Gus Mutscher, all of whom were closely tied to the old Democratic establishment. The two front-runners in the race, Frances (Sissy) Farenthold and Dolph Briscoe, benefited from the public backlash against incumbents. The contest between Farenthold and Briscoe also reflected the nature of the transition at work in the Democratic party. Farenthold drew her strength from liberals and college students. But in his victory the politically conservative Briscoe effectively split the liberal coalition by securing the neutrality of organized labor. The trend was toward more moderate, establishment-backed Democratic candidates.

In the 1972 presidential election the GOP again demonstrated that it could carry Texas in national contests. In fact, from 1976 through 1992 Democratic presidential candidates failed to win Texas. Republicans also proved they could successfully challenge Democrats for control of state politics when Bill Clements won the governor's race in 1978. His victory further sparked the ascendancy of the moderates in the Democratic party, and in 1982 a new generation of Democrats came to power in Texas. The warchests of incumbent United States senator Lloyd Bentsen and incumbent lieutenant governor William P. Hobby, Jr., aided the election bids of challengers Mark White for governor, Jim Mattox for attorney general, Ann Richards for state treasurer, Gary Mauro for land commissioner, and Jim Hightower for agricultural commissioner, all of whom won in the general election. These candidates benefited from and represented the more moderate to liberal position of the state Democratic party.

In the 1970s and 1980s the Democratic party in Texas also appeared more open to the interests of women and minorities. Groups such as the Mexican American Democrats and Texas Democratic Women gained a greater voice in party affairs. Also, women and members of minorities could now be found in elected positions from the governor down. Nevertheless, the state GOP continued to gain strength into the early 1990s, demonstrating its ability to compete not only in gubernatorial and senatorial races but in such down-the-ballot offices as state treasurer, agriculture commissioner, state Supreme Court justice, and railroad commissioner, as well as in various county and local posts. By 1990 Republicans also held about a third of the seats in both houses of the state legislature.

In the early 1990s the GOP also successfully gained control of about a third of the Texas congressional delegation. Before the 1950s, Democrats had controlled the entire delegation. In 1993 the GOP held both United States Senate seats in Texas after Lloyd Bentsen became secretary of the treasury. The growing strength of the Republican party among the Texas delegation served to dilute the power of Texas Democrats in Washington. Compared with the 1950s, when Rayburn and Johnson controlled the House and Senate as speaker and majority leader, Texas Democrats in the 1980s and 1990s managed to retain only a few key chairmanships in Congress. However, after the election of William J. Clinton as president in 1992 Texas Democrats played a role in the executive branch, with Bentsen at the Treasury Department and Henry Cisneros as secretary of housing and urban development, despite the fact that Clinton did not carry Texas. Previously, Democrats had to win Texas in order to win the presidency; no Democrat had won the White House since Texas entered the Union in 1845 without carrying the state. But Clinton was elected, and Texas Democrats' political clout in Washington declined.

The Republican lock on about a third of the state's electorate by the early 1990s had a double impact on the Democratic party. It encouraged the development of a more moderate leadership for party machinery and pushed some individual Democratic candidates to try to appear more conservative than their Republican challengers. Thus, even though the fledgling GOP in the 1950s and 1960s developed on the political right, the hopes of liberal activists in the 1950s and 1960s for establishing a liberal Democratic party in Texas were at best only partially successful, since the revamped moderate Democratic party had difficulty retaining control of elected offices in the state. In 1994 Republicans regained the governor's office, retained the office of agricultural commissioner, gained all three seats on the Railroad Commission, and picked up two congressional seats.

See also LATE NINETEENTH-CENTURY TEXAS, TEXAS IN THE 1920S, TEXAS SINCE WORLD WAR II, and GOVERNORS.