New York City’s Frontline Workers

Frontline workers have always been the lifeblood of our city. Nurses, janitors, grocery clerks, childcare staff, bus and truck drivers. Every single day, crisis or no crisis, these are the essential workers in our city, our economy, and our society. The COVID-19 crisis does little to change that reality, it only brings into sharper relief these vital New Yorkers, who number more than one million workers amid today’s crisis, or 25 percent of the city’s workforce.

And yet, these same workers whom we trust with our health, our nourishment, our loved ones, and our lives are too often ignored, underpaid, and overworked. They very often lack healthcare, have to travel long distances to get to get to work, and struggle with childcare. Many in New York City are also undocumented, meaning they do all of the above while living in fear of deportation under the current federal administration.

If there is any collateral benefit to the COVID-19 tragedy, it is that the labor and contribution of those in our social service, cleaning, delivery and warehouse, grocery, healthcare, and public transit industries have finally received the attention and respect that they are due. How well we protect, compensate, and care for these workers, then, will be the ultimate litmus test for what we’ve learned from this global pandemic.

This report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, provides a detailed, demographic profile of these non-governmental workers—and the public employees who get them to work—so that the City, State, and Feds can better address their needs and citizens can better appreciate the struggles confronted by those who toil every day on the frontlines of this pandemic—who they are, where they live, where they’re from, how they get to work, their childcare and healthcare needs, and their financial stresses. To that end, the following serves as both a profile and a guide.

Who are our Frontline Workers?

More than 60 percent of all frontline workers in New York City are women, including 81 percent in the social services and 74 percent in healthcare. Staff in the transit and delivery industries, on the other hand, are only 24 percent and 22 percent women, respectively.

Chart 1

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

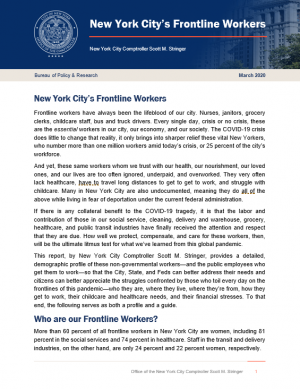

Meanwhile, 75 percent of all frontline workers are people of color, including 82 percent of cleaning services employees. More than 40 percent of transit employees are black while over 60 percent of cleaning workers are Hispanic.

Chart 2

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

More than 50 percent of frontline workers are foreign born. The building cleaning services employ the highest share of immigrants (70 percent), followed by healthcare (53 percent) and food and drug stores (53 percent).

Chart 3

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

In total, 19 percent of frontline workers are non-citizens, often placing them in a precarious position in this age of arbitrary and egregious ICE crackdowns. Over a quarter of food and drug store, 22 percent of social service, and a striking 36 percent of cleaning service employees do not have citizenship status.

Chart 4

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Where our Frontline Workers Live

Those who care for New Yorkers are, more often than not, New Yorkers themselves. Approximately 84 percent of the frontline employees who work within the five boroughs reside here as well. Looking at individual industries, 91 percent of social service employees, 88 percent of grocery and drug store, and 87 percent of cleaning services workers live within city limits.

Chart 5

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Brooklyn is home to the largest share of frontline workers, with 28 percent residing in the borough—including 31 percent of social service employees and 30 percent of those employed in public transit. The boroughs of Queens and the Bronx follow, housing 22 percent and 17 percent, respectively, of employees in frontline industries.

Chart 6

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

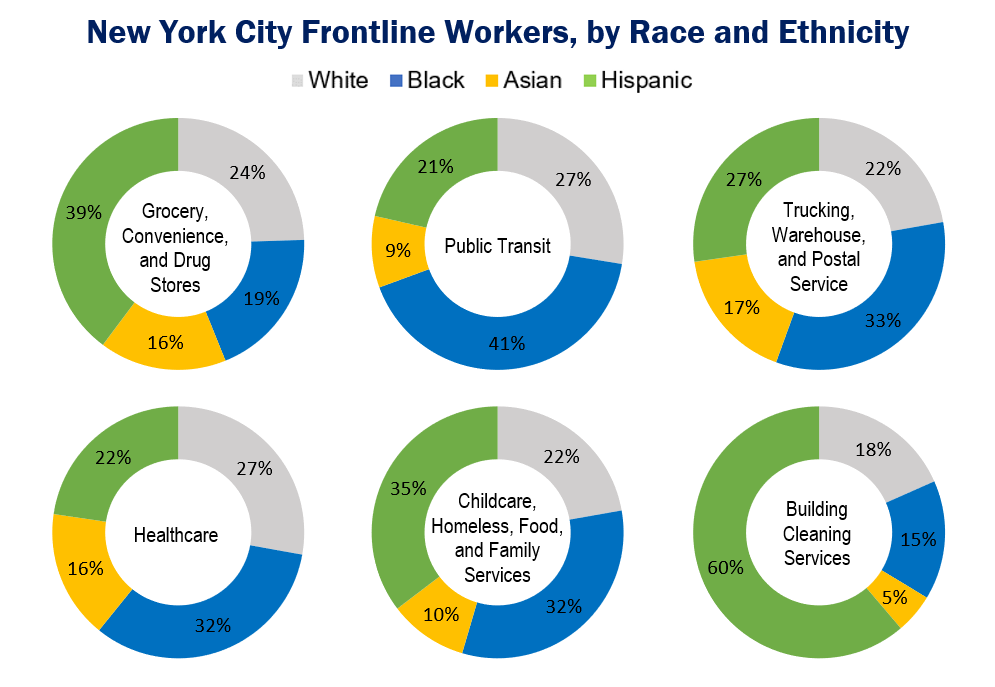

Drilling down to the neighborhood level, there are more than 20,000 frontline workers living in five Brooklyn, three Queens, two Bronx, and one Manhattan neighborhood. Leading the way are Canarsie/Flatlands (34,340), Jamaica/Hollis (31,697), Queens Village/Cambria Heights (24,680), Washington Heights/Inwood (24,626), Castle Hill/Parkchester (24,443), East Flatbush (24,223), and East New York (22,016).

Chart 7

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Whether living in the Bronx, Brooklyn, or Long Island, New York City frontline workers rarely own the home in which they live. In total, 59 percent are renters, including 74 percent of those in cleaning services, 68 percent in social services, and 66 percent in food and drug stores.

Chart 8

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

How Our Frontline Workers Get to Work

Living in the outer reaches of the city and traveling to work sites scattered throughout the five boroughs, day-to-day commuting is an arduous task for many frontline workers. The average frontline worker, in fact, will spend 45 minutes traveling to work each day and another 45 minutes traveling back home to their families and loved ones.

Prior to the pandemic, 55 percent of frontline workers used the subway, bus, or rail to get to work each day—with just 32 percent arriving by automobile. Another 10 percent travelled by foot or bike. Workers within the cleaning services (70 percent) and social services (60 percent) industries are the most reliant on public transit.

Chart 9

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

In total, frontline workers account for 30 percent of regular, pre-pandemic bus commuters and 20 percent of subway commuters, as well as 11 percent of rail commuters. This helps to explain why bus ridership has seen a smaller drop (70 percent) than the subway (87 percent), LIRR (76 percent), and Metro-North (94 percent) with the spread of COVID-19 in New York City.[2]

Chart 10

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Importantly, these frontline commuters have very different travel patterns than the standard 9-to-5 straphanger. As has been painfully clear in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, the city’s store clerks, drivers, nurses, and janitors must work around the clock to serve clients in need. As such, 50 percent of all frontline workers, 70 percent of public transit employees, 61 percent in delivery and storage, and 59 percent in building and cleaning services rely on public transit in the off-peak hours (outside of the 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. rush). This underlies the absolute importance of regular subway and bus service at all hours of the day.

Chart 11

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Compensation, Benefits, and Family Responsibilities

Long hours, arduous commutes, caring for the basic and fundamental needs of humanity—this is daily life for our frontline workers. And yet a disturbing 8 percent of frontline workers live in households at or below the federal poverty line ($26,200 for a family of four) and 24 percent live at or below twice the poverty line ($52,400 for a family of four). Moreover, 39 percent of workers in cleaning services, 35 percent in food and drug stores, and 34 percent in social services live in households at or below twice the poverty line.

Chart 12

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Meanwhile, 22 percent of cleaning services workers, 15 percent of grocery and drug store, and 12 percent of delivery and warehousing employees do not have any health insurance. In other words, those New Yorkers guiding us through this global pandemic and most likely to be exposed to COVID-19 would be forced to suffer serious financial hardship if infected.

Chart 13

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

With no healthcare and low wages, caring for a family can be a challenge for frontline workers. In total, 48 percent have a child at home, including 53 percent of public transit employees and 53 percent of cleaning services workers. This underlines the importance of affordable and easily accessible daycare, both during the crisis and afterwards.

Chart 14

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Finally, a disconcerting 37 percent of frontline workers are over the age of 50, including 48 percent of transit workers and 45 percent in the building cleaning services. Given that COVID-19 can be more severe and even deadly with older patients, this reinforces the dire need to keep our frontline workers safe.

Chart 15

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Recommendations

Given this demographic profile, Comptroller Stringer offers the following recommendations to help support New York City’s frontline workers in this time of crisis:

1. Provide Free Protective Gear and Priority Access to COVID-19 Testing to all Frontline Workers

The City and State should help provide free protective equipment and gear—including gloves, masks, and hand sanitizer—to all businesses that have frontline workers interacting with high volumes of people and potentially contagious conditions. Meanwhile, workers at the MTA, hospitals, grocery stores, and other frontline industries should receive priority access to COVID-19 testing when symptoms warrant.

2. Access to Hotel Rooms and Housing for all Frontline Workers who Wish to be Closer to Work or Avoid Infecting Family Members as well as for Healthcare Professionals Coming in from Out of Town

The City and State should work with local hotels—many of which are largely vacant—to reserve blocks of rooms for frontline workers who wish to be more proximate to work or are worried about infecting housemates or family members. This should be provided at no cost to the workers.

Moreover, as the pandemic increasingly centers in New York City and healthcare professionals from around the tristate area and beyond come to offer their services, they should also be given access to hotel rooms at no cost to the workers.

3. Hazard Pay and Staffing Supplements for Frontline Workers

Frontline industries should be encouraged to provide additional compensation or hazard pay to all frontline workers, especially those at heightened risk of contracting COVID-19. The City and State should subsidize this hazard pay for small businesses in order to properly compensate workers and help recruit new employees in these high-risk and currently understaffed industries.

Meanwhile, large corporations that have seen a huge surge in revenue on account of this pandemic—like Amazon, Walmart, and Domino’s—but offer minimal wages and no healthcare coverage to many frontline workers, must step up and increase wages and benefits immediately.

4. Guarantee Healthcare of All Frontline Workers

The State and City should ensure access to free healthcare for all direct service workers in “essential industries”—either via Medicaid or otherwise.[3] This should be available during the length of the crisis and thereafter.

5. Strengthen the Safety Net for Independent Contractors as well as Non-Citizens and Undocumented New Yorkers

Many frontline workers, including home health and child care providers and food delivery workers, operate as independent contractors. Not only does this obligate them to pay twice as much in Social Security and Medicare taxes, it also provides them with few safety net protections if they are unable to work due to medical conditions or other factors. In order to protect these frontline workers—and all “gig workers” in this time of crisis—the State must expand its unemployment, healthcare, and other safety net programs to cover independent contractors.

Meanwhile, basic safety net protections must extend to New Yorkers regardless of immigration status, including those who are undocumented. An emergency relief fund could be established in partnership with private partners in order to circumvent federal restrictions.

6. Maintain Robust MTA Service, Especially During the Off-Peak and on the Bus

While MTA ridership has plummeted in the last two weeks, frontline workers continue to depend on the bus and subway to get to work. Prior to the pandemic, 55 percent commuted via public transit, more than half travelled outside of rush hour, and they accounted for 30 percent of all regular bus commuters.

While New York City Transit worker shortages and disruptions are inevitable amidst this crisis, it is crucial that the MTA continue to deliver robust transit service so that fellow frontline workers can get to their jobs and keep our city going.

As the MTA begins to roll out its “Essential Service Plan,” it must closely track ridership and modify service to meet the demands of frontline workers. First and foremost, bus service should be preserved while regular off-peak schedules should be maintained on the subway and commuter rail. If paired with lower fares, strong off-peak service on the Metro-North and LIRR would be a boon to frontline workers living in Westchester and on Long Island.

7. Metro-North and LIRR Should Charge a Flat $2.75 Fare for All Trips into New York City and Provide Free Transfers to the Subway and Bus

While many Nassau and Westchester residents work on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic, very few travel by commuter rail. This is because Metro-North and LIRR charge exorbitant fares while the Westchester Bee-Line Bus and Nassau NICE Bus both offer more affordable fares and free transfers to the New York City Transit subway and bus.

For the remainder of the COVID-19 crisis, Metro-North and LIRR should charge a $2.75 fare for any and all trips into New York City and enable free transfers to the subway and bus. Meanwhile, both the Bee-Line and NICE Bus should run more service directly to LIRR and Metro-North stations—rather than devoting a majority of resources to routes that parallel commuter rail lines.

8. Help Frontline Workers Get to Work by Bike and Foot

Prior to the pandemic, over ten percent of frontline workers commuted to work via bike or foot. This number will and should expand in order to maintain proper social distancing and effective access to work locations. In order to support these transit modes, the City should do the following:

First, the City should offer a subsidy to any frontline worker who is interested in purchasing a bike or e-bike. It can coordinate with major bike retailers and manufacturers—as well as large grocery and drug store chains—to help cover these costs and distribute these bikes.

Second, a free month of Citi Bike membership should be extended to all frontline workers—including grocery store clerks, childcare workers, cleaning services, etc.—not just those employed in healthcare and public transit. The City can help cover these costs by permanently waiving all fees that Citi Bike currently pays for “parking revenue lost from the placement of the docking stations.”[4]

Third, the City should work with the State to lower the speed limit to 15 miles per hour for all nonessential vehicles. Empty streets cannot be an excuse for cars to speed, putting New Yorkers in harm’s way and discouraging biking and walking.

Fourth, the City should expand sidewalk space on dozens of commercial and residential corridors throughout the five boroughs by carving out a lane of traffic and bumping out the curb using temporary barriers, stanchions, and planters. Expanding this space will allow for appropriate social distancing without blocking essential ambulance, sanitation, utility, and delivery traffic. Moreover, the City DOT has ample experience with these sidewalk bump-outs and can do this work quickly.

And finally, roads running through parks or those that do not travel along commercial or residential neighborhoods should be shut down altogether and opened to bikes and pedestrians. This can include Forest Park Drive, Mary Corbin Drive, the Mosholu Parkway, and the Jackie Robinson Parkway.

9. Free and Easily Accessible Child Care for all Frontline Workers

This week, the Department of Education opened up Regional Enrichment Centers for the children of “essential workers” deemed critical to the COVID-19 response efforts. The approximately 100 RECs will offer both early childcare centers as well as K–12 sites for the children of first responders and health care workers, transit workers, sanitation workers, and City agency essential staff.[5]

While this is an important first step, these resources must be immediately ramped up to serve frontline workers in all frontline industries—including the grocery, delivery, social service nonprofit, street vendor, building cleaning, and building security services.

In addition to providing free and high-quality child care to all frontline workers, the City and State should create a centralized tool to connect them with available slots in their neighborhoods, including community-based family child care providers.

Meanwhile, family co-payments for subsidized child care should be waived for the duration of this emergency, with corresponding increases in reimbursement rates to publicly-funded child care providers.

10. Deep Cleaning Subsidies, Supplies, and Staffing

The City should create a fund to help small businesses and nonprofits with day-to-day cleaning and sanitizing expenses—as well as “deep cleaning” expenses following a confirmed employee COVID-19 infection. It should also expand transitional work programs (like Shelter Exit Transition) to put vulnerable job seekers to work in cleaning services and other frontline industries.

11. Empower Frontline Workers by Bolstering Pathways to Citizenship and Enacting Municipal Voting

Over half of frontline workers are foreign-born and nearly one-quarter are non-citizens. Without citizenship status and voting rights, many are completely disempowered in our political system. This explains, in part, why so many frontline workers lack decent wages, healthcare, and a robust social safety net.

To rectify this situation, both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the City of New York must bolster pathways to citizenship and enable non-citizen voting in all municipal elections. A Citizenship Fund should be created to subsidize the cost of all relevant application, course, and legal fees.

Meanwhile, all New York City residents with green cards and legal work papers should be permitted to vote in local elections. It is only fair that those who pay taxes and provide essential frontline services to all New Yorkers should have a direct say in municipal affairs.

Methodology

For the purpose of this report, “frontline workers” consists of direct-service, mostly non-governmental employees in the grocery, pharmacy, transit, delivery & storage, cleaning, healthcare, and social services industries. While some of these industries do include public employees—e.g. hospitals and public transit—the social service workers highlighted here are largely employed by the non-profit and for-profit organizations that make up the vast majority of direct-service work.

The data in this report looks at workers within industries, not occupations. This means, for instance, that a janitor employed by a financial services or design company—rather than a building services company—would not be included.

The industry-groups discussed in this report consist of several sub-industries that correspond to the following Census Industrial Classification Codes:

- Grocery, Convenience, and Drug Stores: Grocery and related product merchant wholesalers (4470), Supermarkets and other grocery stores (4971), Convenience Stores (4972), Pharmacies and drug stores (5070), and General merchandise stores, including warehouse clubs and supercenters (5391).

- Public Transit: Rail transportation (6080) and Bus service and urban transit (6180).

- Trucking, Warehouse, and Postal Service: Truck transportation (6170), Warehousing and storage (6390), and Postal Service (6370).

- Building Cleaning Services: Cleaning Services to Buildings and Dwellings (7690).

- Healthcare: Offices of physicians (7970), Outpatient care centers (8090), Home health care services (8170), Other health care services (8180), General medical and surgical hospitals, and specialty hospitals (8191), Psychiatric and substance abuse hospitals (8192), Nursing care facilities (skilled nursing facilities) (8270), and Residential care facilities, except skilled nursing facilities (8290).

- Childcare, Homeless, Food, and Family Services: Individual and family services (8370), Community food and housing, and emergency services (8380), and Child day care services (8470).

Endnotes

[1] Workers under the census industry code “services to buildings and dwellings” include job classifications such as janitorial services, carpet and upholstery cleaning services, exterminating and pest control services, and other services. Workers providing these services could include contracted workers at commercial office buildings, retail establishments, and other locations. These workers are also majority immigrant and/or persons of color, are essential frontline workers and in need of the protections outlined in this report. Workers who are employed directly by businesses outside of the “building cleaning services” industry are not included in the data.

[2] Goldbaum, Christina. “Subway Service Is Cut by a Quarter Because of Coronavirus,” New York Times. March 24, 2020.

[3] https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-issues-guidance-essential-services-under-new-york-state-pause-executive-order

[4]Velsey, Kim. ”Citi Bike to Pay New York $5 M. Annually for Parking, Not Much Else at the Moment,” Observer. November 20, 2014.

[5] https://www.schools.nyc.gov/enrollment/enrollment-help/regional-enrichment-centers/rec-parent-overview