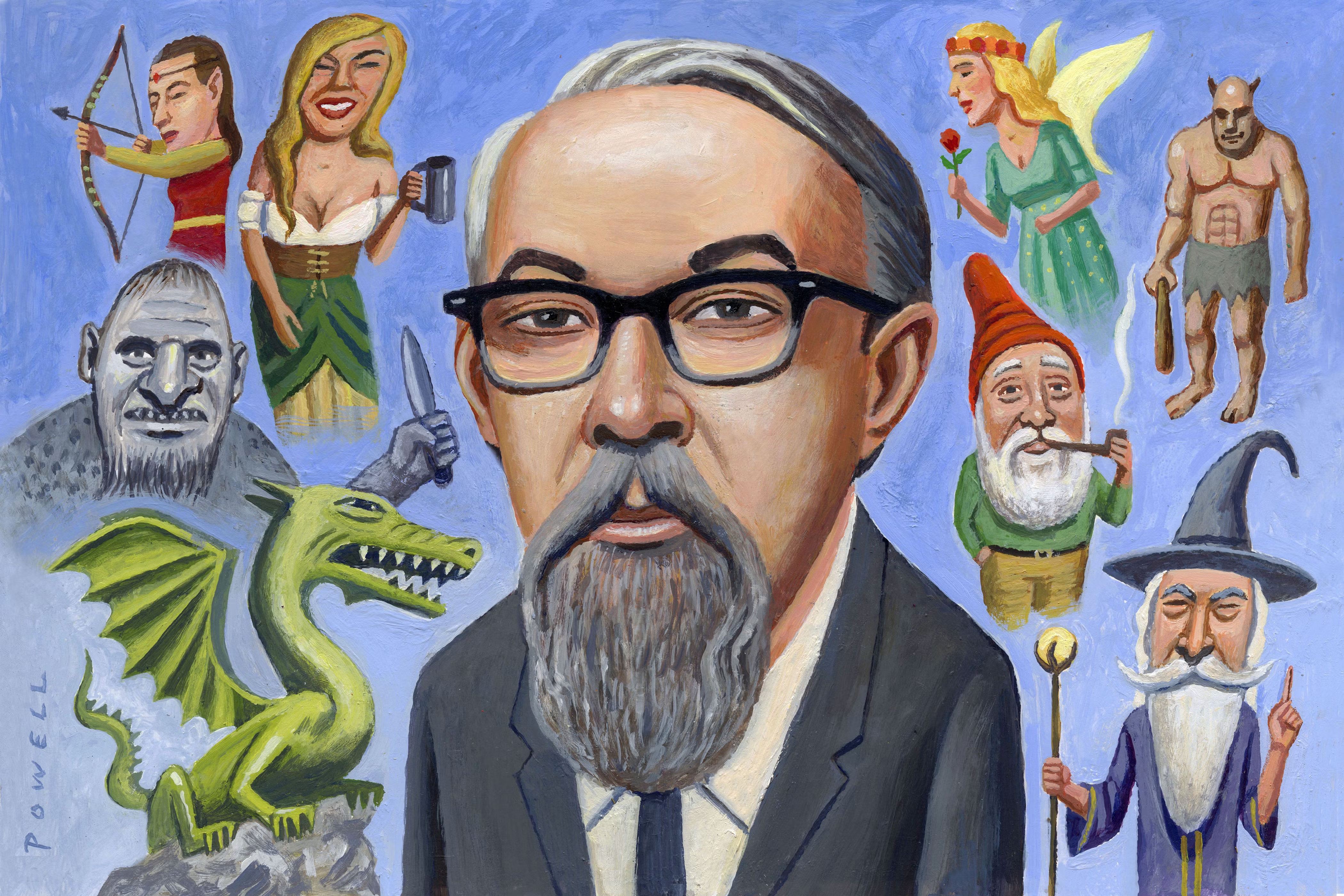

Lester del Rey wore 1950s-style horn-rimmed glasses, an unruly billy-goat beard, and his silver hair brushed back above a big forehead. He liberally dispensed cards that said: Lester del Rey, Expert. He sometimes said his full name was Ramón Felipe San Juan Mario Silvio Enrico Smith Heathcourt-Brace Sierra y Alvarez-del Rey y de los Verdes. He was in fact born Leonard Knapp, son of Wright Knapp, in 1915 in rural southeastern Minnesota, subject to the Minnesotan fever—Jay Gatz, Prince Rogers Nelson, Robert Zimmerman—for reinventing oneself. In 1977, del Rey, then in his 60s, turned his proclivity for fabulism to profit: He invented fantasy fiction as we know it.

I always thought fantasy had existed forever. Elves and wizards were old. Stories about them must have been, too, drawn from deep history, passed from generation to generation, just as my dad read J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings to me when I was 6. Part of the magic of these tales is the sense that they have always been this way; it’s thanks to that continuity with the past that we’re able to touch the enchanted premodern world, a place that hasn’t yet been rationalized by capitalism and science. With C.S. Lewis’s Lucy, I, too, walked through the wardrobe to Narnia. By middle school in the mid-1990s, I was ripping through the books of Piers Anthony’s Xanth series, with its basilisks and ogres, which were by then regularly landing on the New York Times bestseller list.

But it turns out that fantasy, as an enduring publishing genre, is hardly older than I am. All sorts of things had to go right—and wrong—to make it happen. Book publishing and retailing were revolutionized in the 1970s. Lester del Rey took advantage of that revolution, realizing that readers were hungry for derivates of Tolkien. Piers Anthony, a prolific sci-fi writer, volunteered to write one to order. In 1994, I thought I was reading Anthony’s Xanth novels to access an ancient tradition of enchantment. To the publishing industry, I was reading them because I was precisely the modern consumer they expected and needed me to be: an upper-middle-class suburban kid in a shopping-mall Barnes & Noble. This is the story of how del Rey did it.

Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature

By Dan Sinykin. Columbia University Press.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Lester del Rey once narrated his life for a group biography of science fiction writers, though it’s unclear how much of what he said is true. He said that when he was 12, he spent the summer with a traveling circus; that when he was 13, he hitchhiked west, picked fruit in Washington, worked as a water boy for lumberjacks in Idaho, then returned home. At 16, he went east to enroll in George Washington University, dropping out two years later, at the height of the Great Depression. According to the biographer, “To survive, he sold magazines door to door, worked in restaurants, and did research for a man working on a WPA bibliography of music in the United States.”

Meanwhile, he became an avid reader of science fiction, which in those years circulated primarily in pulp magazines. He was obsessed with John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction magazine after its launch in 1937, repeatedly writing letters to the editor. When a girlfriend dared him to write a story himself in 1938, he sent it to Campbell, figuring his name would be familiar. Campbell published it, and, later that year, a second story, “Helen O’Loy,” about a man who falls in love with the patriarchal ideal of a fembot, which became, in time, a widely anthologized classic. (It is absurdly sexist.) Del Rey got by working odd jobs for another decade, finally making it as a full-time writer in 1950, the year he turned 35.

Four years later, in England, J.R.R. Tolkien published The Fellowship of the Ring, the first book in The Lord of the Rings, which set the template for everything to come. Tolkien was a professor of medieval literature at Oxford and drew from Beowulf and Icelandic sagas to create Middle Earth, populated with dwarves and elves, dragons and wizards, and, of course, hobbits. The Lord of the Rings did not sell well in the United States until a decade later, in 1965, with the publication of competing cheap mass-market editions by Ace and Ballantine. Then it became a campus sensation, supplanting The Catcher in the Rye and Lord of the Flies as the novels of choice for disaffected youth. Cultural commentators compared the frenzy to Beatlemania, and termed LOTR fandom—with its accompanying Elvish and ubiquitous “FRODO LIVES!” buttons—a cult.

Publishing, at the time, was a gloriously inefficient industry. Boozy lunches, chummy deals made between college pals, ample socializing. Most houses were still owned by their founders, or by their heirs. But this was changing fast. In 1965, RCA, big in defense contracts and television manufacturing, acquired Random House. CBS acquired Holt, Rinehart and Winston in 1967. Time Inc. acquired Little, Brown in 1968. And so it went, with once independent houses swallowed into conglomerates. Meanwhile, new innovations at the book distributor Ingram made it possible to distribute trade paperbacks and hardcovers at an unprecedented speed and scale. When shopping malls began proliferating in the expanding suburbs, B. Dalton and Waldenbooks took advantage of the distribution revolution with their chain bookstores.

This was the new publishing industry that Lester del Rey joined in 1974, invited by his fourth wife, Judy-Lynn del Rey, a talented editor. She had been an English major at Hunter College, where she studied James Joyce. Afterward she found a job as a gofer at Galaxy, a science fiction magazine, which introduced her to the genre. She quickly rose through the ranks, becoming the magazine’s managing editor. When Betty Ballantine, who cofounded Ballantine with her husband Ian, decided to retire, she chose Judy-Lynn as her successor. Judy-Lynn joined the company in 1973, the same year Ballantine was acquired by Random House, and thus was owned by RCA; she brought Arthur C. Clarke’s latest novel with her as her first title.

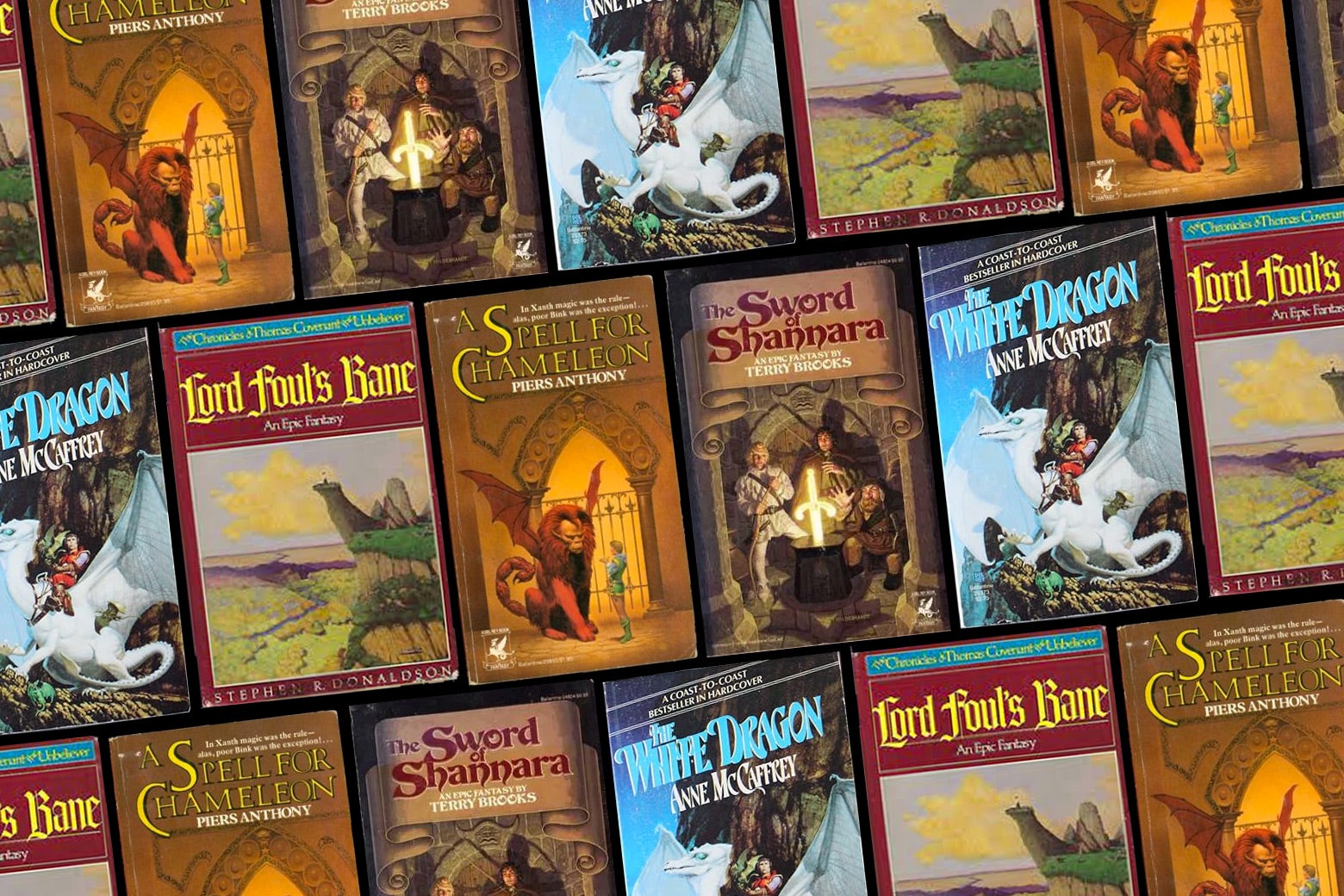

Lester had been a working writer for a couple of decades, deploying pseudonyms that included John Alvarez, Marion Henry, Wade Kampfaert, Erik van Lhin, Edson McCann, Charles Satterfield, and Philip St. John. Judy-Lynn wanted to bring Lester on as an editorial consultant, and as the most envied editor in science fiction, she had professional capital to spare. A big manuscript had come in over the transom, a work of epic fantasy by Terry Brooks. Judy-Lynn didn’t know much about sword-and-sorcery books, but Lester did. She passed The Sword of Shannara to him. He read it: It was a page-turning Tolkien rip-off. Many editors might have been dissuaded by the derivative imitation—many critics later were—but not Lester. He saw possibility. He saw a whole new genre to populate. Lord of the Rings stood alone in the marketplace. The Narnia books were for children. “There’s nothing else out there for them to read,” he told Publishers Weekly, about Lord of the Rings fans. “They just have to reread their Tolkien.”

Not that others hadn’t tried. The best effort had happened right there at Ballantine, where editor Lin Carter had launched a mostly-reprint “adult fantasy” series in 1969. The books sold poorly, but did, as demonstrated by scholar Jamie Williamson, establish something of a fantasy canon for the emerging genre. The series folded in 1974, just as Judy-Lynn was bringing Lester to Ballantine. Lester told the president of Ballantine he’d join the staff if he and Judy-Lynn could launch her new imprint—Del Rey—with epic fantasy and with Terry Brooks’ The Sword of Shannara as the lead title. Lester would acquire Del Rey’s fantasy list and Judy-Lynn its science fiction.

That president, Ron Busch, had come to Ballantine with directions from Random House to make the house “a contender in the mass market major leagues.” That meant, Busch said, something like “turning a successful, innovative boutique into a Bloomingdale’s or Macy’s.” In other words, he needed to ramp up production and sell more books. The conglomerates that owned publishing houses were demanding quarterly growth, a challenge with inflation ballooning and wages stagnating. Discretionary budgets were shrinking. People had less money for books. Harlequin, a romance publisher, had established a successful strategy: Pay small advances for formulaic genre books, preferably series, with built-in audiences.

Del Rey believed that strategy could work for fantasy. The problem was that until Terry Brooks, no one had tried hewing to a formula close enough to The Lord of the Rings—conveniently a trilogy, sell three books instead of one—to hook Tolkien’s enormous fan base. For Ron Busch, the del Reys were a godsend: ambitious editors with an idea to churn out inexpensive books for an underserved market. Confident, eccentric, and experienced Lester del Rey had an idea, and Busch let him run with it.

Lester understood how to sell to the mall bookstores, B. Dalton and Waldenbooks. “Those two chains rule the world,” he told authors, and the chains had specific limits for genre fiction: Novels should only reach a certain length; Waldenbooks would only stock titles with initial print runs upward of 20,000. Lester also was not preoccupied with artistry. He disdained academics, professional critics, and highbrow novelists. He wanted to give the people entertainment. And he couldn’t wait on submissions for a genre he had only just invented—he had to build it from scratch—so, according to fellow editor David Hartwell, he contrived a formula. “The books would be original novels set in invented worlds in which magic works. Each would have a male central character who triumphed over the forces of evil (usually associated with technical knowledge of some variety) by innate virtue, and with the help of a tutor or tutelary spirit.”

This precisely describes Piers Anthony’s Xanth novels, the books I devoured as a tween. Anthony was a fortysomething science fiction writer, born in England but living in Florida, the grandson of a wealthy mushroom tycoon. When he caught wind that the del Reys were launching an imprint, he wrote to ask to take part. Lester let Anthony in on the formula—or, we might say, given its intoxicating effect on so many young readers, the spell.

In 1977, Judy-Lynn and Lester launched Del Rey at Ballantine. The fantasy list was led by Terry Brooks’ The Sword of Shannara, Piers Anthony’s A Spell for Chameleon, and Stephen Donaldson’s Lord Foul’s Bane. All sold massively, with Brooks’ book reaching No. 2 on Publishers Weekly’s trade paperback bestseller list. (The science fiction line also contributed to Del Rey’s instant success, thanks in large part to Judy-Lynn’s snapping up novelization rights for Star Wars, which sold nearly 4 million copies that year alone.) A books columnist at the New York Times wrote in December that 1977 had been the year Americans went nuts for fantasy. “They’re making hardcover best sellers of books about gnomes, pixies, hobbits and other Middle‐earth creatures. They’re grabbing up large quantities of albums by such fantasy illustrators as Frank Frazetta. They’re buying 600,000 copies of the 1978 Tolkien Calendar.”

It was a durable trend. Tom Doherty founded Tor in 1980 to publish science fiction, fantasy, and horror. Ace, Bantam, Berkley, and DAW each developed fantasy lines. TSR, the publisher of Dungeons & Dragons, launched its Dragonlance series in 1984; the books sold extraordinarily well at the chain bookstores. Not all fantasy was formulaic. With such explosive growth in the market, there was room for writers like C.J. Cherryh and Anne McCaffrey, who wrote stories that didn’t necessarily center men. Yet in 1990, Tor used Del Rey’s Sword of Shannara playbook from 13 years earlier to launch its new series, The Wheel of Time, by Robert Jordan: “We looked at how Del Rey made Terry Brooks and we did that,” editor Patrick Nielsen Hayden told Publishers Weekly.

In 1994, I entered the Barnes & Noble in the mall by my house and found worlds upon worlds on the fantasy shelves. How could it ever have been otherwise?

Judy-Lynn del Rey died in 1986 at the age of 43. Lester rejected a Hugo Award given to her posthumously. He said, “I cannot accept an award given her for dying.” Lester del Rey died in 1993. The fantasy genre has only grown in the years since. The Harry Potter books, published for children, became enormous hits with adults as well. In the early 2000s, authors like Susanna Clarke, Neil Gaiman, and China Miéville became bestsellers with literary subversions of fantasy tropes. The release of the Kindle in 2007 opened a vast realm for self-publishing, where fantasy has proliferated into countless microgenres. Queer and nonwhite authors such as Tamsyn Muir and Nnedi Okorafor have embraced fantasy and are in turn celebrated on BookTok, a TikTok subculture with outsize influence on book sales in the 2020s.

Lester del Rey was a strange Minnesota farm kid with a wild imagination and a knack for business. He intuited that what millions wanted from a publishing industry urgently optimizing to keep up with capitalism was to escape the modern age into a world where capitalism and industry had never happened. There is magic in that. At least I thought so, as a kid. But there’s also, in del Rey’s vision, a formulaic—let’s face it, industrial, rationalized—conception of culture and a pernicious nostalgia that courts sexism and white supremacy. Today, fantasy is, along with romance, our wildest, most flourishing genre. It might not be this way were it not for Lester del Rey, even if his legacy now is as the wizard so many writers and readers choose to battle against.